The Bstroy Conversations

“The greatest stories ever told – the hero's journey, from Star Wars to the Bible – work in an arc. It doesn’t work in a straight line.”

Virgil Abloh

In November 2019, the late fashion titan Virgil Abloh went to Atlanta for “Figures of Speech,” a touring exhibition that involved collaborations with local designers in each city to create fashion lines for museum gift shops. For the show’s stop at the High Museum of Art, Abloh decided to tap Atlanta-born, now New York-based “Neo-Native Design House” Bstroy for the intervention. Established in 2013 by high school friends Dieter “Du” Grams and the mononymous Brick, Bstroy had never been invited to present work in a museum before – but they had envisioned it since day one. Parents were invited. Posts were made. Dreams were coming to fruition after years of hustling. But on opening day, Bstroy was not on view. After months of delays and broken promises from the museum, Abloh had informed them that their hometown museum, wanted nothing to do with them.

Bstroy exists at a timely crosshair between two major focal points of the fashion world: high fashion and streetwear. The label is a part of the post-Abloh, post-Yeezy generation – inheritors, mentees, and consultants to the figures that took over the fashion world and changed its rules forever. Closely tied with the A$AP Mob, the New York creatives who defined the culture of the early 2010s and whose encouragement inspired the duo’s move to New York in 2015, Bstroy’s story owes as much to controversy as it does to collaboration. Their shows—one staged at a train station, another at a hospital, another at a funeral parlor—routinely scandalize media and have even drawn the involvement of law enforcement. Bstroy are the sort of punks the fashion world has not seen since their other late hero: Alexander McQueen.

Two months prior to being ousted from the High, Bstroy staged their fifth-ever show, “Samsara,” at New York Fashion Week. The presentation included a series of sweatshirts distressed by bullet holes and listing the names of school shooting locations, including Sandy Hook Elementary School. The garments were never intended to be sold as ready-to-wear—they were works of art, according to the designers, and they were meant to send a message. But the internet didn’t like how they decided to deliver it. Bstroy’s Instagram page was bombarded with angry comments, blasting the brand for trying to “profit” from tragedy. The story made national news, and Bstroy lost their moment at the museum to the outcry. The embargo didn’t last. As Internet drama gave way to a global pandemic, Bstroy rallied. What follows is a diary following a year’s worth of conversations between me and a brand not only determined but seemingly destined to rise.

December 2020: Banned from the Giftshop

Some friends who were just as unemployed as I was after graduating during the pandemic invited me to Atlanta to campaign for the Democratic senate candidates. I relented, my liberal arts heartstrings tugged – and enticed by the promise of a quick paycheck. I didn’t know many people there – and hadn’t left the house since March – but photographer and filmmaker Zhamak Fullad happened to be in town to shoot a music video and said she would take me out. A few intros to her crew of creative pirates later, and I was invited to hang out at the set-up for “Atlantwerp”: a Bstroy pop-up and, I learned, their third such event in their hometown since moving to New York. “They’re cool,” Zhamak said of her friends Brick and Du, “and Virgil Abloh might be there.” I didn’t know much about the fashion world then, but I knew what that meant.

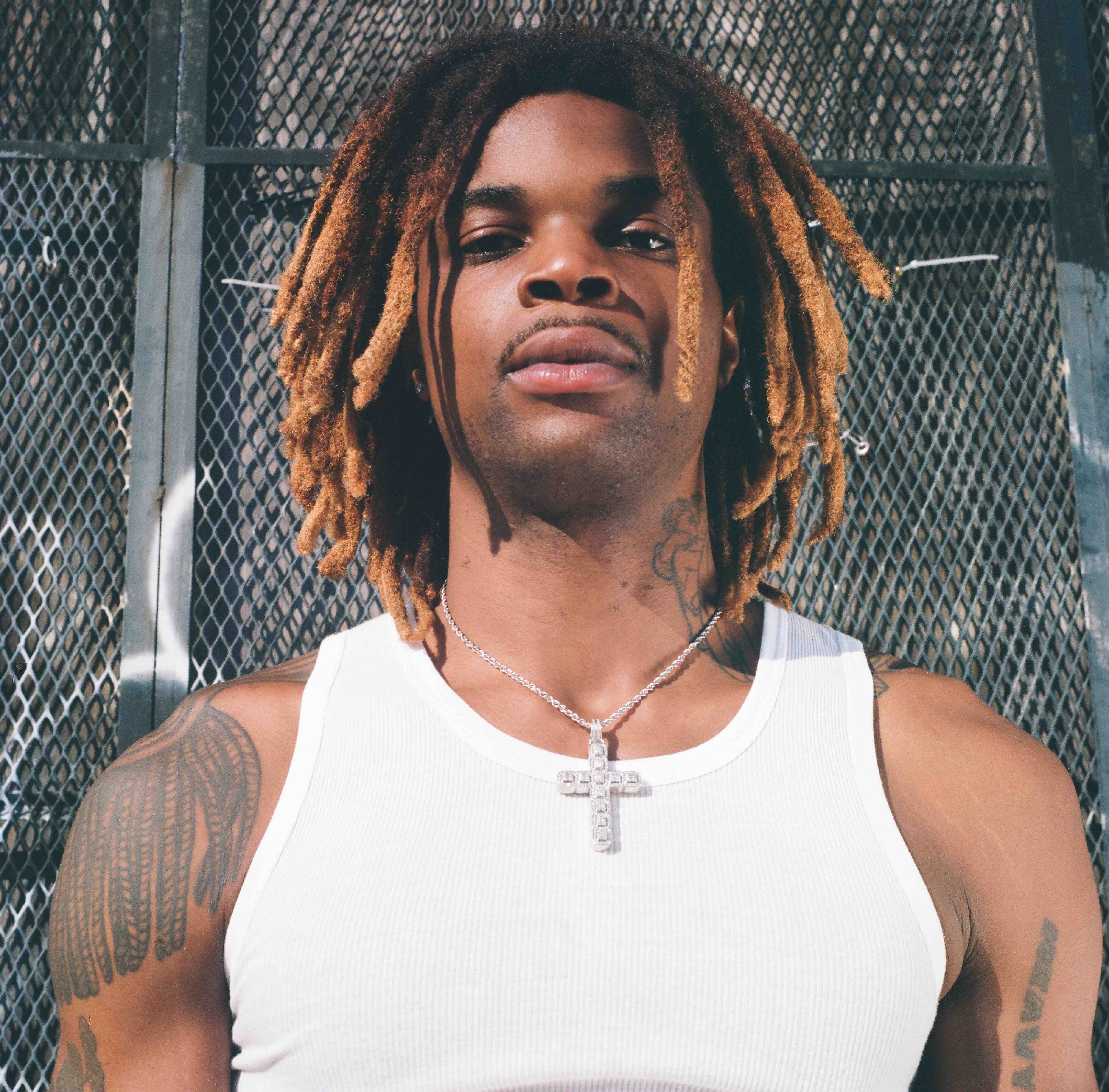

I drove my borrowed Subaru station wagon to an empty storefront and park its gorilla-taped bumper next to a mint condition gray 2004 Porsche 911. I walked inside, where I passed a stack of chrome mannequins, piles of yellow bricks, and a huddle of dudes standing around, glued to their phones and wearing some of the coolest clothes I had ever seen. I found my friends talking to a tall man with shoulder-length dreads draped over his eyes, and I complimented his shoes – Off-White Jordan 5s. He chuckled, “Thanks, I know the dude that made them.” Hand-written on the side in quotation marks was what turned out to be his name: “Du.”

He asked if anyone had any bud and I told him I had an ounce on me. “Where you from, bro?” I told him I’m from Oakland, but the weed was from D.C. “Alright, Cali, roll up then.” A little faded, I began helping set up for the pop-up, slowly. A man with a chiseled jawline and a headwrap rushed into the shop carrying a bunch of boxes, too focused on work to greet anyone. But when he saw my outfit, he stopped for a double take. I was wearing a red Champion hoodie, black Levi’s 501s riddled with holes, and brown Timberlands stained with the collateral damage of a summer spent painting houses. I looked like Take Care-era Drake with an iron deficiency. “Why?” he said, kept walking. I think he genuinely wanted to know.

May 2021: You Didn’t Know You Needed a Toaster

I later learned that the man with the boxes was Brick, Du’s other half in the brain trust and the “face” of Bstroy, an externally imposed moniker he reluctantly accepts. I returned to Atlanta to catch up with him in May 2021. Bstroy’s “Atlantwerp” pop-up had been a success, and the merch had ended up in Lil Uzi Vert and Lil Yachty music videos. Brick – quick-witted, charming, self-assured, and adamant about being accurately represented – met me at a high-end restaurant, where we spoke over oysters. When he found out I’d never had them before, he ordered them immediately. He wanted me to try oysters, but he also wanted to take me out of my comfort zone. Wearing the same headwrap, plus Jordans and a Jordan brand t-shirt, he kept his Céline sunglasses on the entire meal.

We were the only people of color in the restaurant, and Brick was the only man not wearing a button-up. He ordered hot tea, passing on alcohol. He told me that he began to design clothes because he had no other means of expression. “I think we are all given a gift and I just happened to know what mine was early on,” he mused. “God placed Du in my life, someone with an appreciation and understanding for the arts. I can see something one way, he can see it the other. It’s that feeling that it gives—a very eureka moment, a euphoria almost.”

Brick was raised on the west side of Atlanta, in a more affluent area than where Du is from on the east side of town. “I grew up with nice things,” he said. “My parents worked very hard to provide for me and be supportive of the things I wanted to do.” After his mother lost her job when Brick was 15, money became tighter. He went out and got jobs – which both developed and helped satisfy his taste for designer clothes. When he met Du on Myspace, he had found someone who shared his interests. “I don’t know how the fuck we found each other, but I accredit it to the universe,” he told me. “You’re just hoping to God that someone is into the same shit as you —or you’re just a fucking nerd.” Brick went to Kennesaw State University to study economics and would spend summer in the city with Du, who was enrolled at Emory University.

Brick started building a portfolio while working in high-end retail, eventually becoming the style intern at Complex. The closer he got to fashion, the more irritated he became by the holes he noticed in the market. “It’s just like, yo this is cool, but I wish it wasn’t so dark blue. I wish it was purple. Or I wish this shit was polka dot instead of checkerboard. I wish the sleeves had little knick-knacks.” The irritation was productive. Wanting to realize their own vision for garments, Brick and Du founded Bstroy.

The transition from friends to creative partners was easy. “I think it starts with curiosity,” Brick explained. “We’re brothers, we work together, but we have different tastes. I try to give him something that rattles his brain a bit and he likes to give me something that rattles my brain a bit. And from there, we’ll talk. That’s where the magic starts. It becomes an experiment. That’s the high for me.” Brick also compared Du to RZA. “Sometimes you love it, some days you fucking hate it,” he said. “He’s always been like that. It’s not some newfound persona.” But what Brick and Du have attempted to create together was totally new. “It’s our job to solve a problem that people don’t even realize exists,” Brick said. “You didn’t know you needed a toaster until the toaster was invented. It’s that far ahead in terms of how we approach things. That’s how it starts. Once I get that feeling, my intuition tells me that we’re on the right track. ‘This has to happen. The world has to see this. This has to live in the world.’ And from there, that’s where it goes.”

Brick’s sophisticated, no-bullshit attitude is matched in Bstroy’s designs and inspirations. “Du and I always had this great appreciation for militaristic things,” he explained. “They exude function and form, mostly designed by engineers and not fashion designers. It serves a purpose.” Bstroy’s work is almost investigative, an impirical attempt to answer questions: What if you had a giant pocket in your jacket so you didn’t have to carry a bag to the airport? What if you shot up a hoodie at a gun range? Bstroy’s high-octane experiments seek new possibilities from the materials that give them form, sometimes in the brutally familiar. The old cliché from someone standing in front of a Jackson Pollock – “my kid could have done that” – has probably been said about Bstroy. But your kid didn’t do that. Bstroy did.

"It’s something you do without asking for permission, and it is only based on your own work ethic and your intelligence.”

Summer 2021: The Flyest Criminal

A few weeks after oysters with Brick, I met Du at his apartment in New York City. The beautiful two-bedroom’s huge windows overlook the Harlem skyline, and the interior is dominated by bookshelves and endless rows of shoes. The décor includes a framed photo of Thriller-era Michael Jackson, stuffed lambs from a Brooks Brothers store display purchased from a vintage boutique. Pierrot Le Fou was playing on a giant flatscreen when I arrived, but no one was watching. A gorgeous woman with a kind smile greeted me then returned to Du’s bedroom. We go down to the garage and hop into Du’s Porsche, the same one that was parked outside the pop-up. He told me it’s the first car he has ever owned, after dreaming of owning one since he was a teenager. “I come from a traditional hustler upbringing,” he said. He is the ninth of ten kids whose parents were often out of the house, working to support the family. “The kids had to raise themselves, and the outside was raising the kids,” he recalled. “I always wanted to be in control of my own destiny. If it’s not me, it’s God. Not another person.” When Du was 14, he established his first dope trap. “A lot of the time, I thought I had it bad, but I had homies that had it a lot worse,” he explained. “But for a traditional hustler upbringing, that’s standard. You have to fight for yourself and not take ‘no’ for an answer.” Du had just enough to survive, but, like Brick, he wanted more than just survival. “If you want extras, you might need to go rob and kill.”

Du grew up quickly. His peers didn’t expect him to go to college, but Du took a chance on himself and applied to Columbia, Duke, Howard, Cornell, Georgia Tech, and Emory – some of the most elite schools in the country. He was rejected from each one, but Emory told Du if he survived two years at community college, they would offer him admission. “Before I even got to school,” he told me, “I was thinking, ‘Damn, what am I gonna do with my life? What can I steal from college to be able to enhance my life as a criminal?’ Because I knew I was gonna have a criminal life. I believe in crime as an equalizer for the forces against us. It’s something you do without asking for permission, and it is only based on your own work ethic and your intelligence.”

Du came up with the perfect life plan at the intersection of lawlessness and creativity: art thief. “An art thief is knowledgeable,” he explained. “He speaks multiple languages. He’s agile. He’s in shape. He’s the flyest criminal. At the time I decided, that’s my future self. Everything up until now has been progressing to be that person." Once Du landed at Emory, he started selling to rich kids and studying art history. The “thief” part of the plan didn’t last long. “Once I started actually going to classes and shit, I just fell in love with art on its own. I stopped thinking about taking it and started thinking, ‘Damn, this shit is crazy.’ Art is the evidence of man. At any time, art can tell you what was going on. That turned me out. My criminality got pushed to the back burner and now I’m thinking about creating. That’s where Bstroy came from, the decision to create.”

If Brick is the face of Bstroy, Du is its heart. He speaks with vulnerability and discusses his art with the care of a parent speaking about their child. When he told me how he lost his oldest friend at 25, a defining moment of pain in his life, I revealed to him that I also lost my oldest friend, Nicholas, who went to Emory at around the same time he did. Du looked me in the eyes with a degree of pain and told me he gets it—the only satisfying response when sharing your grief with someone.

We crossed Harlem and arrived at the west side apartment the A$AP Mob helped Du and Brick move into back in 2015 – tragically, on the same day A$AP Yams died. When I visited the dimly lit railroad-style space served as a studio. There was a sewing machine in living room and the walls were lined with press clippings, including The New York Times’ 2019 “After Kanye, After Virgil, After Heron,” which featured Bstroy alongside other emerging talents as “The Dissenters” of their generation. I met Ashton, Bstroy’s chief assistant. “He does everything,” Du told me. Ashton has the word “Samsara” tattooed on his neck, the same logo from their 2019 ready-to-wear collection. We had come to pick up Du’s Commes des Garçons x Nike collab shoes, unreleased, and to look through the samples of their “Bistrot” collab with High Snobiety, for which Du was set to direct a campaign video later that day.

Recalling Bstroy’s first runway show in Atlanta a decade ago, “Boys Don’t Cry,” Du explained McQueen’s influence on their punk approach. “He always treated his shows with the same absurdity as the clothes." They wanted to embarrass City Hall and call out Atlanta’s public transportation. “We have a train system, but it’s a facade. It’s a ‘T.’ It goes up and down in the middle and left and right in the middle. How the fuck you use that?” Atlantans either drive – or they can’t get around. “Only the poor, only the Black and brown, only the people who have no other options ride the train in Atlanta.” Bstroy chose Atlanta’s Buckhead MARTA station, in the city’s luxury shopping district and most expensive commercial center. City officials didn’t notice until a video went viral and wound up on the local news, putting Brick and Du on the run from the police for weeks. Luckily, no charges were filed against them in the end. After the event, many MARTA employees applauded Bstroy for bringing attention to Atlanta’s transit problems, and Brick and Du were even invited to redesign the system’s swipe cards. Staying true to their protest, the duo declined.

Du took me on a mission for shrimp – and banana pudding for his girl – a two-hour ordeal back and forth across town in rush hour traffic. I asked him why he chose to drive in New York. “You can be the flyest dude in the world. You can have all the money you could possibly want. You could afford as many Ubers as you can pay for. But nothing beats picking a girl up in your own car. Nothing.”

September 2021: Like a Fossil

After our shoot for this article we went to Brick’s apartment to celebrate with Prosecco and tequila. Bstroy’s clothes had just been featured in Sneeze magazine, and their museum dream, thwarted by the High, had come spectacularly true. In America: A Lexicon of Fashion had just opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where their Doublehead Hoodie and Sailor Track Pants from the 2018 “Sweet Screams” collection is displayed alongside looks by such labels as Rodarte, Ralph Lauren, Thom Browne, and Off-White. “Society will create boxes, and if you’re not in the box you’re not a part of the club,” explained Du. “If you’re a Black boy from the hood in America, what are your options? He knows he can play basketball. He knows he can sell dope. We’re just changing what it means to that boy. We speak for a kid that is not yet spoken for in this room. That introduces the possibility for other people. It changes the shape of the whole simulation. Other people can do what we do. People can imagine themselves in places they didn’t think possible.”

I asked them if they ever imagined being in the Met. “Yes," Brick affirmed. “Wholeheartedly, yes.” Their inclusion confirmed the radical change in what high fashion, and art, can be. “When another fashion house goes through the same process as we do to make their garments, why is that limited to street wear?” Brick asked, “Why is it deemed lazy? Why is there a moving goal post of what genius is? We’re able to define the narrative.”

As an art historian, Du has long understood that to make art is to mark the passing of time, and to contribute to a societal archive meant to outlast the creator. “It’s like a fossil,” he said. “We approach every collection like we’re looking into a crystal ball,” added Brick. “Like we know what the future holds.” Du explained that all their shows are treated as art works with a message. This was true of the controversial Samsara, which sought to reveal the psychological decay that leads to such horrific acts as school shootings. “Look at the ugliness,” Du explained of their call to action. “Look at the ugliness we try so hard to forget.”

Samsara recalled the phenomena of punks wearing sweatshirts from Columbine High School following the 1999 shooting, a gesture meant not to glorify violence but to disturb the public and serve as a reminder of America’s faults. “It was an update for this category of garment,” said Du of the medium – clothing – that, most likely more than the message, caused the controversy. “It needed to be offensive because it was new, it hadn’t been done. No one was gonna do Sandy Hook because it was too touchy. Everyone in their right mind was going to skip it. But it takes a crazy person to say, ‘That’s the one, that’s the one that’s going to touch them right where they feel it, make them think.’” The loudest critics came from outside of the fashion world, and the claims they made were old: that fashion is superficial and money-obsessed, and that degenerate streetwear designers were trying to make a buck off of tragedy. But Samsara was couture – which, as the Met’s extensive collection proves, shares its rarefied status with art, as a type of object meant to be observed and considered, not sold en masse. “That’s why it’s important for people like us to be in the Met so that later on people view us as smart without assuming that we’re lazy,” said Brick. “Lazy is probably the worst thing you can say about someone who busted their fucking ass.”

“Everything is imaginary,” said Du. “You tell yourself you’re great every day because the world tells you you’re not shit. And you gotta be like, ‘I am.’”

“Even if we did think we could be great, that doesn’t compare to actually seeing your shit in the Met,” added Brick. “When the things Du and I create click in such a divine manner—it leaves you at a loss for words. So, when you ask, ‘Did you expect to be in the Met,’ I answer, ‘Yes,’ not even on some arrogance, it’s just bigger than us.’”

“Bigger than us,” Du repeated. “I can’t even explain this shit, bro.”

“Kinda gets you fucked up though,” said Brick, “because it’s like, how do you go big on big?”

I asked if Bstroy had any advice for the young Black person growing up in the hood we had spoken about earlier. “It’s tone deaf to go, ‘Just follow your heart!’” said Du after taking a moment to meditate on it. “Our shit was so specific. It’s hard to tell you how slim the margin is. To be listening to Kanye and then ten years later to be consulting him, for him to be asking us what’s cool and giving us money in exchange – I don’t know how to tell a kid to get there.”

The usual combination of hard work and chance—meeting on Myspace, then meeting A$AP Rocky—was probably part of it, but Bstroy’s philosophy is that you have to know with your whole heart what it is that you want to do, then do it as if you are obligated to. “Let me make it deeper for you,” said Du. “It’s a natural thing that humans do: we think about what would happen if we ended it. But if you decide, ‘Alright, I’m gonna stay, I’m gonna live,’ something clicks in your brain that you have to live life a certain way. If I’m gonna live, I’m gonna fucking do it this way. That’s what kills the art – if you worry about how it’s received. If you do something with pure intention without worrying about how it lands, for me that’s total transparency, total honesty, total vulnerability as an artist.”

Du seemed to have figured it out. “That’s my advice: do something you can do by yourself and don’t care if nobody shows up for it. I guarantee you you’re going to excel. The day that everybody else relaxes because they got a bad review, you’re going to keep going because you don’t give a fuck about the review. Your contemporaries may take a day off because it was a blow to them; they can’t believe this person said this thing about this because that’s their purpose, that’s the goal, the reception of it. When you’re old and gray you can look back and care about what they say. It’s hard because a kid who sees you and wants to be like you doesn’t understand that he’s not going to exist in the same environment that he admires you in. You need to prepare for a world that doesn’t even exist yet. I can tell you how to be the greatest clothing designer but what if twenty years from now the thing to be is a fucking veterinarian? What if veterinarians are running clothing design? You got an outdated skill set. So, I just say ‘follow your fucking heart and listen to the most immediate moment’ because you cannot do what Kanye West did to be Kanye West – he already did it. Whatever it is that’s going to take you to wherever you want to go, it hasn’t been done yet.”

December 2021: “After Virgil”

Abloh passed away not long after our celebration at Brick’s. His death shocked even those who were aware of his illness. The thought of a fashion world without its gate-opening Saint Peter caused the community to question: how easy would it be for the powers that be to relock the very doors he had blast off their hinges?

When I visited “In America,” I was greeted by a 1989 Ralph Lauren American Flag sweater displayed alongside other designers’ riffs on the classic, including “Tyson Beckford” sweater by Tremaine Emory of Denim Tears, embroidered with the Pan-African American flag. Abloh’s hand was present throughout, as palpable in work by those he mentored as it is in his own. Bstroy’s imposing installation contained three mannequins and two gray double-hooded sweatsuits, one of them worn, as it was by on the “Sweet Screams” runway, by two models as though “craving companionship.” Above the trio was a single word, “CLOSENESS,”and below, its definition: “The state of being in a very personal or private relationship; the state or condition of being near.” The presentation addressed a “dystopian future of loneliness and isolation,” according to the catalog, embodied by the limp second hood laid with the weight of the world on the solo wearer’s shoulder. This is fashion for the “neonatives” Bstroy imagines will inhabit the Earth post-apocalypse, preparations for that world that “doesn’t exist yet.” Missing from the Met’s description, however, is that whoever is sharing the two-headed hoodie can secretly hold hands or pass things back and forth underneath it. Maybe that’s how Abloh handed them the keys to the fashion world, or at least the instructions to pick its locks. What Bstroy promises is an inversion of Abloh’s pognant goodbye note: “Virgil was here.” Bstroy has been and will be there, living and creating in a future of their own design.

Credits

- Text and Creative Direction: Saam Niami

- Photography: Michael Janey

- Styling: Bstroy

Related Content

VIRGIL ABLOH: “Duchamp is my Lawyer”

“I AM THE LEADER”: YE (KANYE WEST) in Conversation with TINO SEHGAL

The Leadership Secrets of Gucci Mane

Indefinite Optimism: A-COLD-WALL*’s SAMUEL ROSS

BEINGS SUPREME: “Give Us This Day Our Daily RED”

Old Town Fury Road: LIL NAS X, “Daddy Lessons,” and the Black Yeehaw Agenda