BEINGS SUPREME: “Give Us This Day Our Daily RED”

|Octavia Bürgel

Google the word “iconic” today, and the hundreds of millions of image search results will be dominated by products, endless products. But what is an icon? From the Greek for “image” or “likeness,” the word appears in English in the mid-1800s, referring to Eastern European Christian paintings of Jesus Christ or other holy figures, venerated and used as an aid to devotion. The “icon,” in other words, brings us mortals one step closer to God.

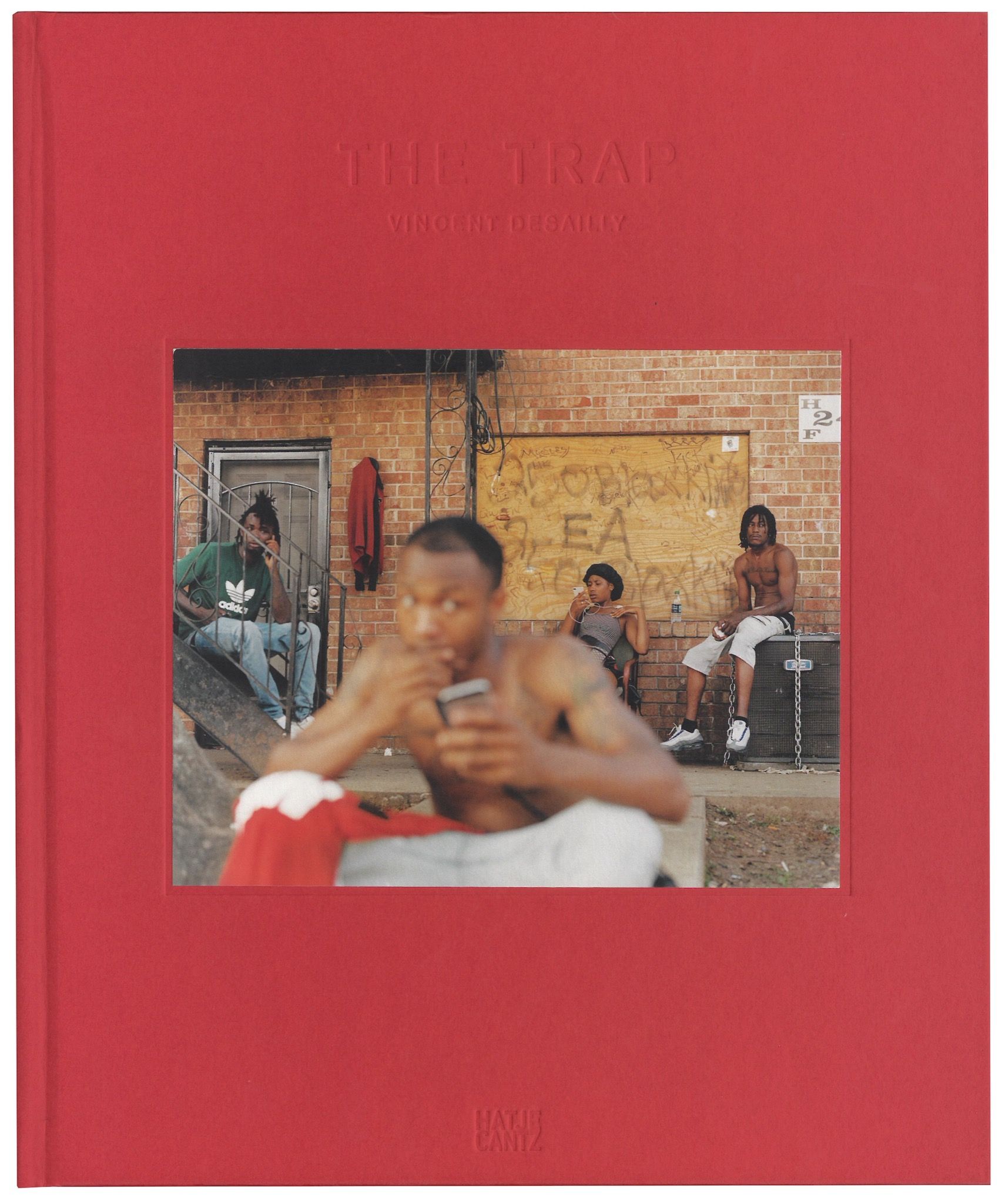

In the 25 years since Supreme first opened its doors at 274 Lafayette Street in Lower Manhattan, the brand has grown from a temple of skate and youth culture into the leader of a global fashion merchandizing Reformation, gathering devotees under its white on red “box logo.” To commemorate a quarter of a century in business, the label offers a product drop of an unusual kind: a glossy, 350-page monograph published by Phaidon Press. Simply titled Supreme, the volume contains an introduction by Carlo McCormick followed by endless pages of archival photographs shot by longtime collaborators such as Larry Clark, Ari Marcopoulos, and William Strobeck.

At once a product of and a prophet for our late capitalist times, Supreme has the capacity to mark its wearers as “inside” or “out”, while constantly distorting the bounds of such membership. To disciples, Supreme is almighty, an indistinct presence embodied in products of devotional significance – “highly-coded fetish objects,” in McCormick’s terms. References to talisman, totem, charm, or devotion are common in texts about Supreme. In 2019, object-oriented ontology (triple O) thinker Graham Harman told 032c: “I see brands as charismatic objects. They captivate you with an allure.” A purchase, Harman continues, conceals its fraudulence by offering a bribe: buy, he says, and “You get this, this, this, and more – and capitalism always needs ‘and more,’ because there’s no product that can satisfy us.” Supreme’s is the ultimate “and more,” offering not only spirit but group membership, acceptance, the opportunity to ritualistically declare allegiance – and protection from outside evils. Supreme is the SPQR tattoo in Russell Crowe’s Gladiator for the modern era. “Are you not entertained??”

Beating the monograph to bookstands by just two weeks was the first of Byron Hawes’ two-volume anthology of Supreme products, Art On Deck: An Exploration of Supreme Skateboards from 1998-2018. The second volume, Object Oriented: An Anthology of Supreme Accessories from 1994-2018, was released in early March. The product images included in these compendia are fun to leaf through, and provide a sense of scale and scope of objects that have been Supremed upon, but there is not much to say about them. The author’s tone is pithy but not enjoyable, and his analysis of the books’ images leaves much or not-at-all to be desired.

Harman continues, “even if you had an exhaustive list of all the things that [a Supreme product] could do– that would still not be the product, because there’s always a surplus to the product… [it] has an internal, independent life that we can never get at directly.” In this sense, Supreme’s Phaidon monograph succeeds: it is not just a book about Supreme products, it is a Supreme product. It shares that animus that all Supreme products share. Hawes’ books, by contrast, attempt to wear it like a sleeve. It doesn’t fit. When the author notes in his introduction to the second volume that he is writing “from [a] dive bar in the LES… at 10:47 PM on a Saturday night,” it lands like an “okay, boomer” meme–complete with misguided usage of African American Vernacular English.

Perhaps one reason for Supreme’s success and resonance among the youth is that it has never attempted to catalogue – and thus to discourage – anything. The skate deck may double as art object, the “Holy Bible” as stash box, the skate tool as one-hitter. The brand encourages versatility, making “this-is-not-that” rules about use value seem parental.

McCormick writes in his introduction: “Supreme was and will always remain a fundamental, unflinching expression of skate culture.” It is hard to believe those words the first time you read them: the brand is too big, its influence too extensive, and its collaborations too high-profile for its ethos to be intact as inherently subversive. But somehow, McCormick’s words make sense next to Hawes’ anthologies. So long as the primary tenet of the cult of Supreme remains a commitment to unregulated pleasure – evident in the name of the brands sponsored skate team, The Fucking Awesome Kids – the “gnarled and gritty” being that McCormick describes will continue to reign, well, supreme.

Don’t be fooled: Supreme is not anti-authoritarian. Whether or not the brand cares to admit it, they are the ultimate decider of “cool” not just for a band of misfits, but for an entire generation. Choose to reject their version on the basis of the label’s ubiquity alone, and you will still be defining yourself along a Supreme-delineated axis. Supreme is a trickster deity – a reluctant authority, a corrupt official ready to drop the charges if the price is right. And that’s probably closer to what the skaters would say, too.

Credits

- Text: Octavia Bürgel