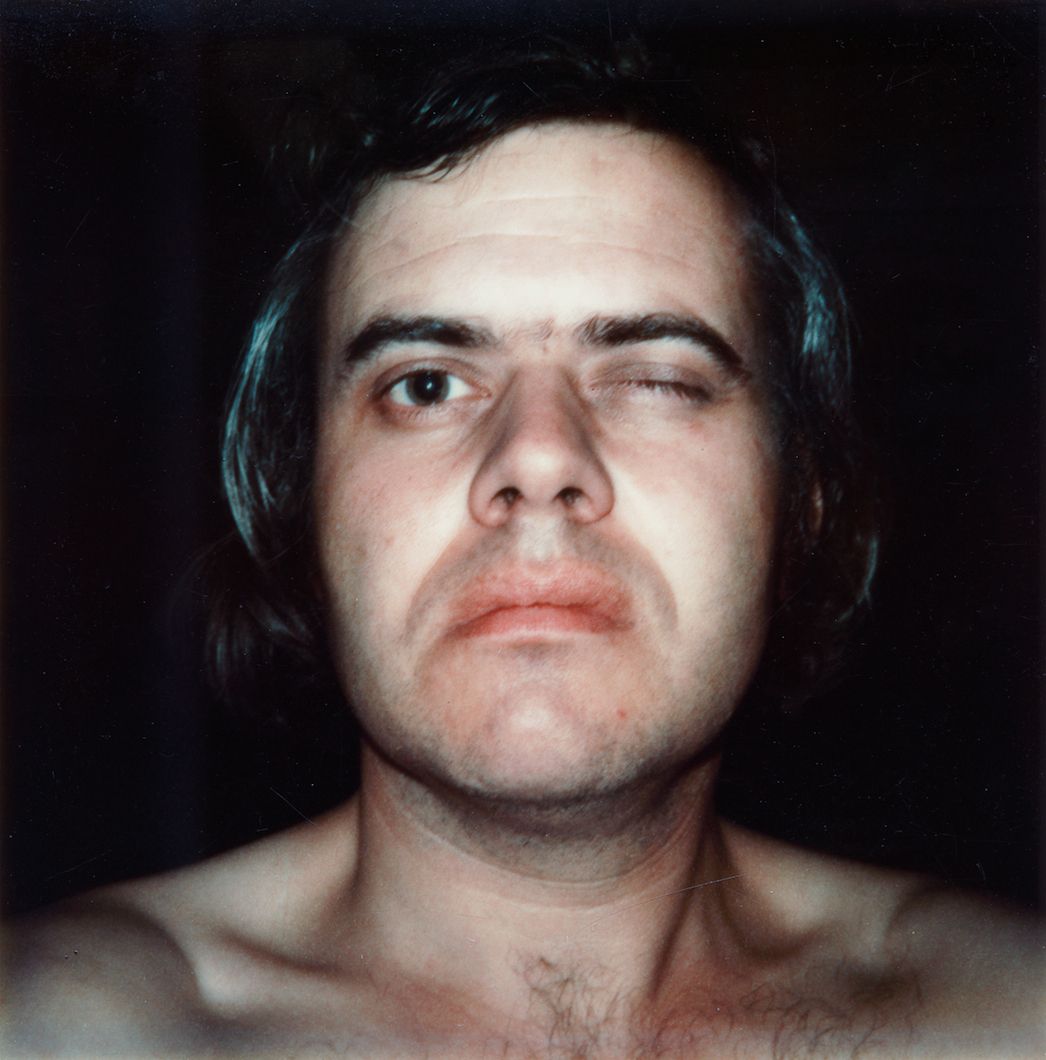

WALTHER KÖNIG, Cologne

|Hans Ulrich Obrist

Congratulations to WALTHER KÖNIG for winning the ART COLOGNE Award.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST buys a book everyday. It is a ritual he started about 20 years ago. He buys the books at different places, wherever he happens to be. But he especially likes to perform this daily Tarkovskian ritual at a place he refers to as “paradise”: the Walther König bookstore.

The legendary business was founded in Cologne in 1969 by WALTHER KÖNIG (b.1939), soon to become one of the world’s pre-eminent addresses for art-related literature and a hotbed of intellectual exchange (apart from the parent location, the bookstore now maintains branches across Germany, in Vienna, and in London).

Around the same time, with his brother Kasper, König also started a publishing house. Today, the Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König is home to many artists, including Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke and Hans Peter Feldmann. Obrist, who has known the bookseller and publisher since he was a young student and has collaborated with him on a series of books, speaks of König with wonder-filled enthusiasm. He points out the publisher’s “incredible generosity,” and is fascinated by the “Borgesian infinity” of the original bookshop’s physical space.

“Whenever you think you’ve seen it, there is another hidden room. Little by little, one discovers, floor by floor, more and more secret spaces – and I am sure I still have not seen all of them, filled with books upon books. It’s almost paradise. I’ve always thought of the König bookshop as a sort of paradise.” It is amid this inner architectural complexity, in König’s office, that the two men sat down to talk about what Obrist sees as a one unified entity: “It’s him – his bookshop, his building, all the books, his publishing – it’s a beautiful, holistic thing.”

Hans Ulrich Obrist: How did it all start? Did the books find you, or was it the other way around?

Walther König: It was actually a coincidence. After boarding school in the country, I went to Berlin. That was before the wall was built. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, so I studied law. I didn’t see much of the school other than the cafeteria, but I did have a great year. In Berlin I saw great theater for the first time and got to know great bookstores, also in the East, and the big Antiquariate [used book stores]. It was a complete El Dorado; you could live very well for very little money. After that year I knew I did not want to study law. I had been working at a small general bookstore on the side, just doing odd jobs and running errands for them. That’s how I first came into contact with the trade and decided to give up law and become a bookseller. I drove across Germany and got stuck in Cologne. There was a legendary bookstore there called the Bücherstube am Dom.

That was pretty well known at the time.

It was very famous. It was one of several bookstores in various cities that were founded during the Weimar years and came out of the Wandervogel youth movement.

And this was in the 50s?

Yes, I applied for an apprenticeship position with the Bücherstube’s owner, Hans Mayer. He became my boss. He was a very special man and I owe my entire profession to him, as well as my passion for books and the book trade. He had founded Bücherstube am Dom in the 1930s with Albert Schulze-Vellinghausen, and it became the meeting place for Cologne’s literary and cultured society. It also had an Antiquariat. I spent seven years there.

But it wasn’t an artist’s bookstore?

No, it was a general bookstore, but at a very high level. It had every kind of department – a Russian section, medical, gardening, etc. – and also a big literary department, which was run by a very interesting man. He had a regular clientele with whom he only talked about the books they had bought from him the last time. He would say to them, “You must experience something.” And as they were talking about the books they had bought on their previous visit, he would walk through the store and collect 3, 4, 5 books and bring them to the cashier. And the people bought them without asking any questions. It was never discussed whether they wanted the books he had picked or not, he just assigned books to each client, if you will.

And how did you become involved with the art book department?

The first Kunstmarkt Köln art fair took place in 1967 – that was the trigger. After two and a half years I was done with my apprenticeship, so Mayer gave me the art department, which was his big passion. Then in ‘68, [Arnold] Bode’s last documenta took place, and I said “Los, Herr Mayer! We have to go to that.” So we both drove to Kassel.

How did that experience change things for you?

I stayed in Kassel for three months, alone, sleeping in one of those uncomfortable rooms they have for truckers at gas stations; it was one of the best times of my career. That’s because it was the first time I came in contact with international artists. But also, you had all the big names and the big paintings in Kassel: Lichtenstein, Morris Louis, Barnett Newman, Kenneth Noland, Olitski, Ad Reinhardt, Wesselmann – things I had never seen before. At the time, only libraries and institutes had foreign books. Nothing came from America or England. So we agreed to only carry foreign books and publications that weren’t available on the German market. Back then, you still had classic exhibition catalogues; totally different from today’s, they were published by the actual museums. In Kassel, things went from local to international.

So that was the opening to the world?

Yes. But I have to add that the American books came through my brother Kasper, who was living in New York at the time. That played a big role. I can remember the first Magritte catalogue came from MoMA; I had never seen anything like it. But it was also totally new for our customers in Cologne, and for my colleagues at the bookstore. You can’t forget that there was a very different attitude towards modern art in Germany at the time. It was always treated as something that you made fun of after discussing politics and sports – “My six-year-old could do that.” In any case, Kasper went to all the galleries in New York and one day he sent a gigantic suitcase full of the most amazing things – the first Bruce Naumann book was in there too.

It sounds like a Wunderkammer.

Exactly, it was fantastic. Kasper had put it all together in New York. These were publications that no one had seen here yet. Germans had a great deal of catching up to do in the early sixties.

What else did you learn during these years?

Everything. To this date, my Lehrherr [apprenticeship master], Mayer, is my biggest role model. He was just such an extraordinary bookseller. He was always in the store and showed us how to handle clients. He also introduced me to all the important people and to the working hours I still keep. He would just say, “Herr König, you should stay this evening; interesting people are coming.” He always had clients that came after the shop had closed. He had an office with an Antiquariat on the second floor with a separate entrance from the store. All these interesting people and collectors visited him there.

No one knew about these rooms?

Correct, and that’s a concept I kind of took over.

So you also have rooms that are not accessible to everyone.

Yes, on the top floor. Very few people have keys to that area. That is one of several methods that I learned from Mayer and still use. Another one is the way we have run our order department from day one. All the books that arrive stay first on big tables. I come in very early in the morning, when no one else is here yet, look at everything and decide where it is going: if it will be offered in a certain department, if it’s a standing order that needs to be sent somewhere, how to enter it bibliographically, if an additional text needs to be prepared for it, which branch gets it, etc. – we have all these big compartments. And that is essential for me, because my whole memory of titles comes from having held each and every book in my hands. Lists of titles or other systems don’t help me remember anything. But if I have actually physically handled a book, then it sticks permanently in my head. Now, as you can imagine, every day we receive mountains of books, so this process can take hours. But keeping it this way is very important to me, and it’s something I learned from Mayer too. If we got a new book about Kirchner for instance, he didn’t explain who Kirchner was, but what literature existed about him, what had been published by or about Kirchner in past years. It’s a genius method to record books in one’s bibliographic memory.

And what happened after your time with Mayer?

Just one more thing about Mayer – it’s good. We would drive to the book fair in Frankfurt in my Opel Admiral, which was more like an American car, long like a ship. Opel made the biggest cars at the time, not Mercedes or BMW. Anyway, at the fair I just followed him around, carrying bags full of books, and he introduced me to all the publishers, because he was incredibly respected. I tell that story because it shows how many doors he opened for me. But then he died. I wanted to go to New York to work for Wittenborn. I had an interview and they offered me a job. But then I didn’t get that damn green card. So, without much thinking, I decided to start my own business, and opened my first shop here in Cologne on Breitestrasse. It used to be the store of a newspaper vendor who ran an illegal bar in the back, and the place had all these restrooms. It was this little space full of toilets: two for women, two for men, and pissoirs. Of course we renovated and changed everything.

When was this?

This was in the March of 1968.

So that was the birth of your publishing business?

No, the publishing house started a year before and was initially called Gebrüder König Verlag. Kasper lived in New York with Barbara Brown, a photographer. At this time, Franz Erhard Walther was in NYC, too. He made a living by decorating cakes at night and that’s where he made his big Werksatz works. Kasper knew Walther well, and wrote to me saying that the two had a great idea for a book: “Hey, why don’t we start a publishing company?” I said, “That’s great, let’s do it.” So he and Walther took all these pictures in New York and made this wonderful book, OBJEKTE, benutzen.

Is it a blue book with red letters?

Exactly. It’s a wonderful book. The texts are like small statements. They sent me these clippings they had cut out of American newspapers and magazines to show me how to typeset it. I didn’t really know how to do any of that, so I went to Ernst Brücher, who owned the publishing house DuMont Schauberg. He was a legendary publisher, very experienced in the business, and you could say he taught me my profession and showed me how to make books.

So, as a mentor, he was for publishing what Mayer was for bookselling.

That’s right.

What was the next book you published?

The next book was House of Dust, by Alison Knowles.

The Fluxus pioneer who did “Make a salad.”

Right. And then she took a more feminist direction. She had written a poem, “House of Dust,” and was friends with a computer programmer. You have to remember, this was 1968. The programmer had access to the big data processing machines of the Pentagon. So he programmed this poem in a way where you have these verses that run continuously without repeating themselves, and it never stops making sense. And they wanted to make it into a book. Then, one day, this huge package arrived from Kasper with magnetic tapes. Now we had a problem, because here in Germany, there was just one computer in the entire country that could process all that data; it belonged to Siemens, which was in Munich at the time. So we got in touch with them and asked if they would print it for us. They said they would and that it would cost around 25,000 Deutsche Mark per hour. Of course, there was no way we could afford that. So we told them, “If you do this for us now, it will be good for your image when it becomes famous.” It worked. They said, “Okay, we will do it for free,” and actually printed it for us. A few weeks later, another package came with an endless pile of folded paper – that old computer paper with the holes on both sides. The stack of folded paper measured a meter and a half in height! By the way, have you seen our first catalog?

No, I haven’t.

Claus Böhmler designed it. It’s a heavy little catalog, and on the cover you see all these big cars parked on the side of the street. There’s a gap between those cars, into which he drew a car. It’s driving out of the parking spot, past all the bigger cars. That’s us! It was so naïve.

I am curious about Cologne’s situation in the 1960s. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

With the exception of London perhaps, to me, Cologne was the best place to be in Europe at the time. For what we wanted to do, Cologne was surely more interesting than Paris. Ludwig showed (the exhibition) “Kunst der 60er Jahre” in the fall of 1968. It had this legendary catalog by Wolf Vostell, which is actually unusable. It has a plexiglas back and is printed on silver and transparent plastic foil. It was an object. So it was a perfect time for a book store, because on the one hand you had Pop art, which was made to be published in books, and on the other you had conceptual art, which emerged around the same time and would have been unthinkable without books.

Would you say optimism was a factor?

It was total euphoria. It was also the time when the term “coffee table book” came about. It was fashionable to be interested in art – and I say that with no value judgment at all. It was just expected, when you had friends over, to have at least one book about Pop art, 60s art or Lichtenstein lying around. That was a positive development. Because some of these people, who were initially just interested in books as social symbols, became serious collectors in time.

Art put Cologne on the map then.

Absolutely. It brought a greater discussion to Cologne. Radio was the other big factor. We had an important broadcasting studio, the WDR. All big composers – John Cage, Georg Brecht, etc. – came to Cologne. That’s how Paik ultimately came to Cologne. So you had two scenes that were closely related. Merce Cunningham came to Cologne a few times – not to Berlin, Munich or Frankfurt.

Would you say Berlin today is comparable to Cologne back then?

Today, Berlin is the undisputed center. That’s where the artists live. In the last two years, 17 galleries moved from Cologne to Berlin, even though the collectors continue to live in the Rhineland. Berlin may not have the enthusiasm of Cologne in the 70s, but it is without a doubt Germany’s artistic and intellectual capital. In our book store on Museum Island, our customers are very discerning, and they ask a lot of us. We all find this an immense privilege, to work in such an intense atmosphere.

But there was something more exciting going on in Cologne in the late 60s and 70s?

That’s right. In 1968 you had the first art market in Cologne, and somehow everyone was completely euphoric. I still remember that’s when I first saw drawings by Hockney. I had never seen anything like that. It is still extraordinary today. I have had tremendous luck in my life, both in business and private life. Today, it would be a lot harder to do the things I did and see the things I saw.

How did the bookstore fit into this landscape?

The bookstore functioned as a kind of meeting place. It took a few years until the big publishers took us seriously and realized that there was a commercial potential behind it. But all the people who were making little books on their copy machines sent us their stuff. I still have all the books from Ed Ruscha, who started his publishing company with Heavy Industrial. He had no money at all, but really fancy stationary on which he wrote to me: “I made a new book. It’s called Lost Angels in the Apartment. It’s 8 Dollars and I’m including one. If you order 3 you get 30% off, and if you order 5 you get 35% off.” So I ordered 6.

And that’s how it was with Gilbert and George too?

Their first artist’s book, Side by Side, appeared with us in 1971.

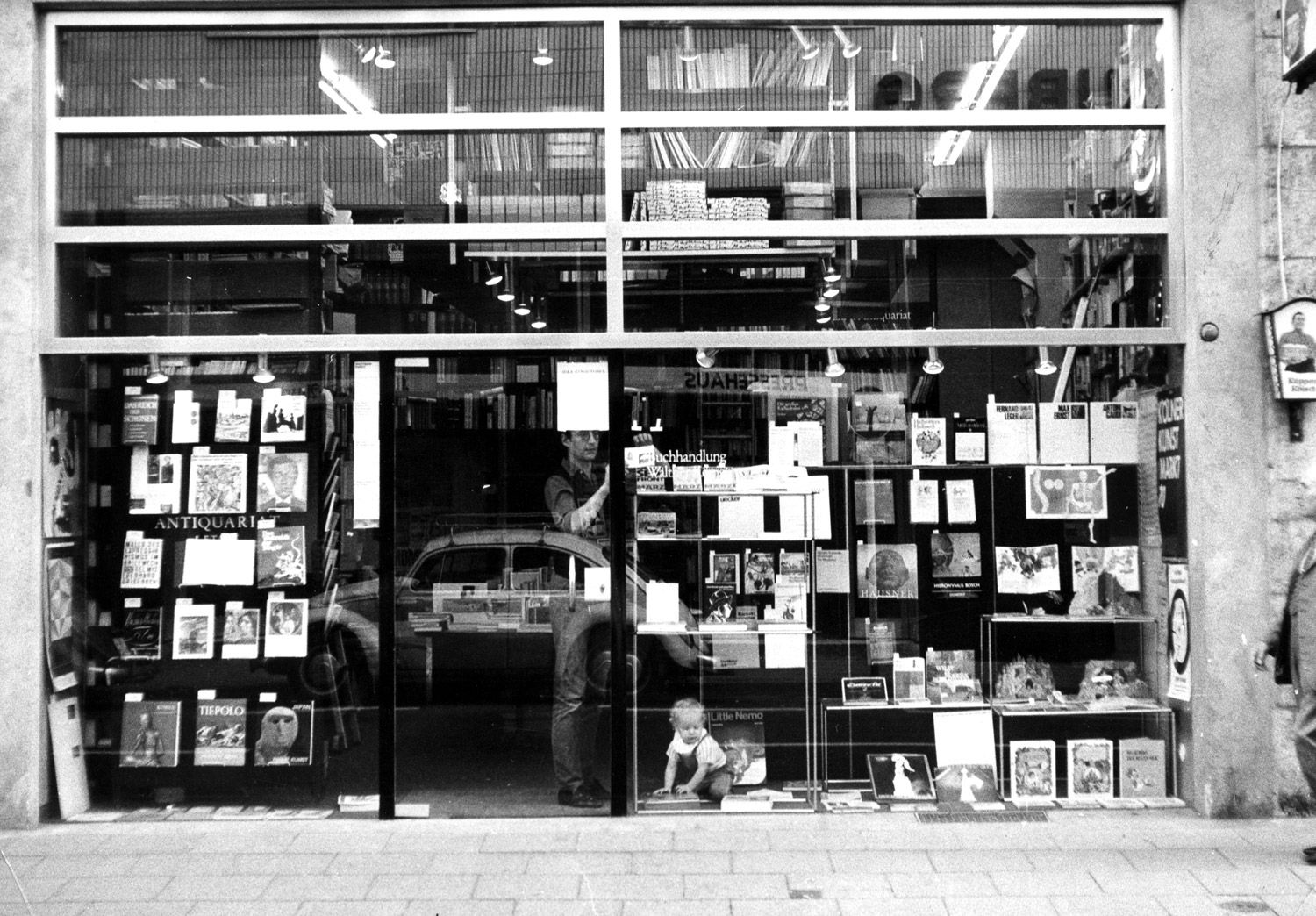

With the famous photo of Gilbert and George and your son Franz as a baby in your window.

Exactly, with little Franz crawling on the floor by the door. We put the entire print run of 500 or 450 in our window, and the two – elegant as ever – are standing behind their books. The photo was never published.

Something else I find important is that you often worked with artists over long periods of time – sometimes 10, 20 or 30 years.

As a small specialized house, we try to operate like a literary publishing house. If we represent an artist, we like to do it completely. That is very important to us – to be an artist’s publisher. We have worked with artists before anyone was interested in them. People like Anna Blume and Bernhard Johannes Blume – he is not a popular artist, yet still, every year we do a book with him. That’s a long-standing collaboration that is important to us. The most successful book we have published is Fischli and Weiss’ “Findet mich das Glück.” We have done 3 books together.

The question book by Fischli/Weiss?

The question book. Peter Fischli called and said, “Listen, I have a new book, do you want to publish it?” And I said, “We will be happy to.” He replied, “But you don’t even know what it is. You’re just going to agree to publish it like that?” To which I said, “We stand by our artists. Even if sometimes that means publishing something that’s not-so-great, we can handle that too.” And it turned out to be the most successful book we ever published.

Tell me about your collaboration with Hanne Darboven. You have always said that was very intense. And you made some almost utopian books with her, certainly some of your most extravagant books.

We came in contact with her very early on. One of our main areas of interest is artist’s books – autonomous works of art in book form. Hanne was perfect for that. Her ideas about book publishing are as radical as the rest of her work. We made incredible books with her. One consists of 127 volumes and Kulturgeschichte consists of 1,800 big plates. We made the Schreibzeit, which is printed on vellum. It is approximately 15,000 pages in 32 volumes. Those are cornerstones of our company’s history. Another book that should be mentioned, which is very important to me, is Hier und jetzt: Tun was zu tun ist, which we made with Jörg Immendorf in 1972. You could say it’s a political artist’s manifesto. These were books we believed in one hundred percent. We were euphoric; convinced the world was waiting for our books, and that they would just be eaten up. So we did these huge print runs, like 3,000 copies of the Immendorf book – you could still get it 2 years ago. The collaborations with important artists lie at the heart of our business, even today.

Speaking of business, we haven’t talked about the Antiquariat. I was in Stockholm a few weeks ago and Daniel Birnbaum showed me this old Antiquariat there. He said this is a very important place for Walther König. So far we talked about book-selling and publishing. Now we need to cover the third dimension: your used-books business. What’s the connection to Stockholm?

The Antiquariat is an essential part of our working universe. There are many books that are of great interest, and I don’t mean for bibliophiles or collectors, but really just as concrete information. For instance, I’m sure there is a Beckmann biography from thirty years ago that made an important contribution to the artist’s reception, but it’s out of print. It’s also not particularly valuable. Still it’s an important addition to what is being offered on the subject at the moment. And because we are a specialized bookstore – and we see ourselves as such, similar to a law or medical bookstore (just that our books are much nicer looking) – it is absolutely necessary to have such items that aren’t generally available anymore ready for our customer. That’s why we have always had an Antiquariat. But there is another explanation. A well-known old-book dealer from Amsterdam once said there was nothing nicer for him than to find a rare, expensive book at a low price and to resell it for more money. I have to say, that applies to me as well. I get a lot of satisfaction from being a business man; I have no interest in being a librarian. I like books, but I like the trade of books just as much. To put it bluntly: buy as cheap as possible and sell as expensive as possible. That definitely appeals to me.

Can you tell me about extraordinary books you are doing with Gerhard Richter?

We are proud to represent Gerhard Richter. The first book we did with him was for the RAF cycle in Krefeld. That was the beginning.

That relationship has intensified in the last 4 or 5 years, which is great.

With Richter, we are especially lucky because he is exceptionally interested in books as an important element within his body of work. So of course his catalogs always look great, but he also sees it as an independent medium that is essential to his general conception. I think the Eis book we just published is one of his greatest works, because it really makes his methods clear – you could even say, somewhat exaggeratedly, his credo. He has an excellent eye and really knows how to translate a very specific vision into a book. You see that in the finished work, which is rare. It’s fascinating to stand next to him and watch him work on these books. Sometimes a book is ready but something is missing, a list “tick,” and it’s difficult to find out what it is. Richter will take the book apart at this stage and lay it out on big tables in his studio. Then he will walk past it for a couple of weeks. And suddenly, one day, he will give the book a new dramatic tension, just by taking page 3 and placing it on position 35, and vice versa, or by tweaking the sequence in other very minor ways. Suddenly it’s right; it just works perfectly. That is a talent. I think books have opened possibilities for him that he did not have before with paintings or drawings. Especially with Eis, he has done new things with those possibilities. I really love this book.

I love that book too. It’s like a toolbox.

I never had an experience like that with any artist; it’s the most interesting thing I’ve ever seen. He also has a great feeling for text. Normally text is only a compositional means – just like the image and the open space. But you can also give in to the text and actually read it. For instance, if you read the text in War Cut, which is actually quite difficult, after a while the eye focuses and sees airplanes and guns – things associated with war. It’s similar with Wald, except here you see bushes and trees. It’s kind of crazy the way the text works. And for Eis, we looked for really long time, until we found this encyclopedia from the 19th Century, before Greenland had even been discovered. It’s fantastic to read this text that’s kind of naive and carefree and talks, for instance, about these little people with bow legs without deforming them. It’s just wonderful. Richter uses all these different layers. I think there are a lot of people who don’t read the text in Eis, who see it only as a formal device, but they should read it. It really adds another punch.

Is there any big project you haven’t done yet? Any unrealized dreams?

Of course I have so many ideas of things I want to do. There is one thing that I never made reality, and that will never be realized the way I would have liked it. For years, Sigmar Polke and I talked about doing a big monograph. He was one of our best clients. No other outsider knew our bookstore as well as he did. He regularly came in whenever he was in Cologne and he was very demanding. He was interested in working on this monograph, but said that he would need time for it. That’s because he wanted to do it himself, instead of delegating it to someone else. He said, “Of course we will find an author. I have a few people in mind, but I have to be present. And at the moment I don’t have the time for it, but as soon as I can, we are going to make this book.”

But he never got around to it.

That’s right, he passed away before we could make this book. He was extremely critical and always had very specific ideas about his books and catalogs. Like the Zurich catalog, which he did all himself – he was very unhappy with it. He was difficult with books, as he was with giving compliments. The last book he made, he said, “You didn’t do too bad a job.” But he was a wonderful bookmaker. We made a book about “Achsenzeit” – the works that were shown at the Venice Biennale and later were hung so poorly at the Punta delle Dogana. It was very important to him and took about a year as well. He talked to our lithographers for hours, exhausted every possibility. That’s why I was very affected by his death, because I know we would have done many more great things together. Now, we are thinking of doing the Monograph without him, but I don’t have any specific ideas of what it might be like. So there are always projects like that, that I would love to do. But I will only tell you about them after you turn that recorder off.

Ok. Before I do that, what about projects that are actually in the works?

We are adding to the block of artist’s books by Gerhard Richter, which over the last few years has become an important, autonomous area within his body of work. After War Cut, Sindbad, 128 Pictures, and Eis, we are about to come out with Patterns, perhaps his most ambitious and radical book to date. It consists of 221 cuts through an abstract painting from 1990, which lead into a new image world, printed in seven colors on plates that are each 80 centimeters wide. Then, in the fall, we will have a new book by Fischli and Weiss and a book by Gabriel Orozco. I’m also excited that we’re releasing Thomas Schüttes Public Political; we have been working on it for over a year.

To end – a question of preference: iPad or Kindle?

Personally, I don’t use an iPad, or a Kindle. I tried it, and think those devices are ideal to perform certain tasks, but they will never replace artist’s books, not even art books.

Credits

- Interview: Hans Ulrich Obrist