Richie Culver: You Can’t Fool Your Hometown

|PHILLIP PYLE

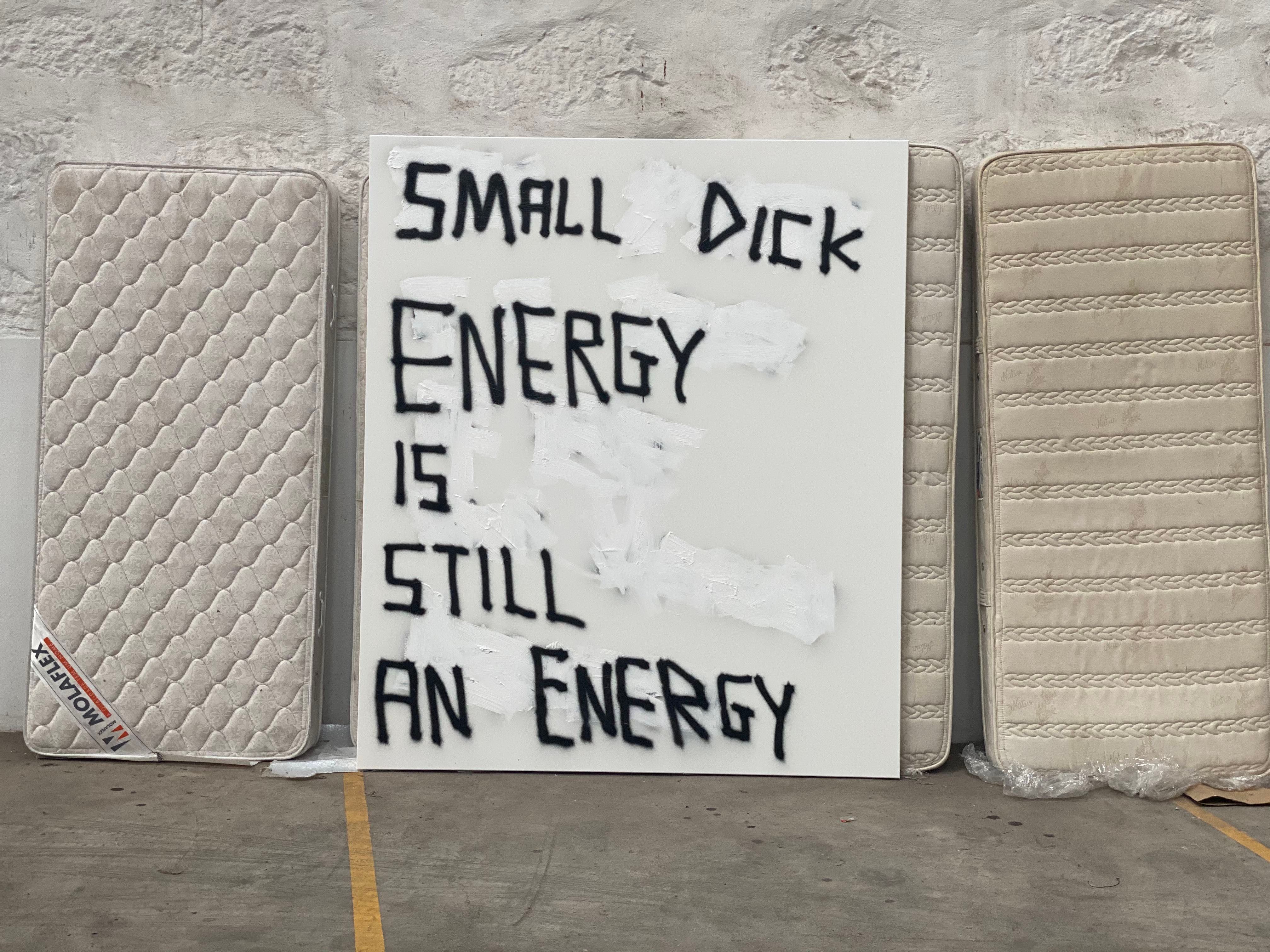

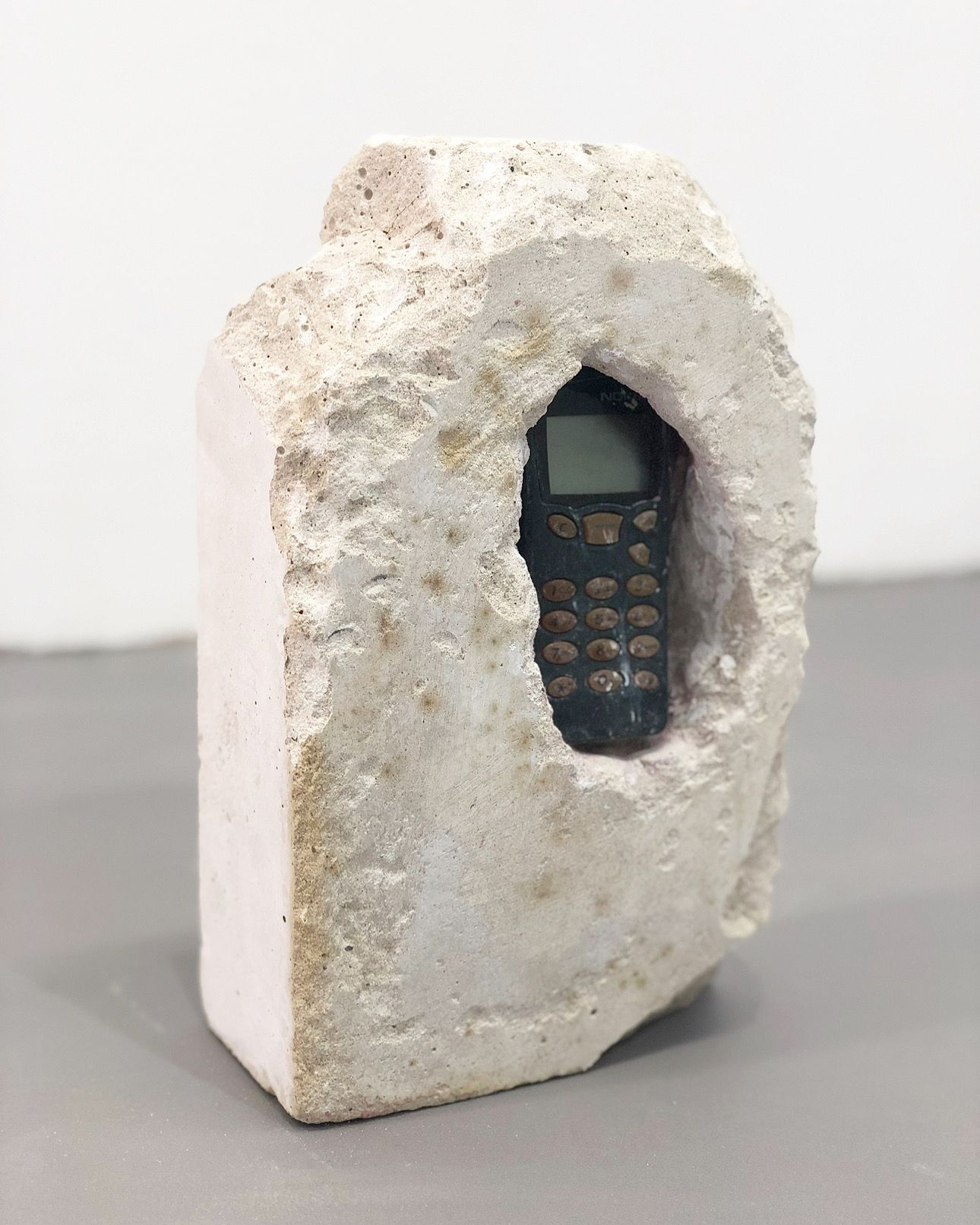

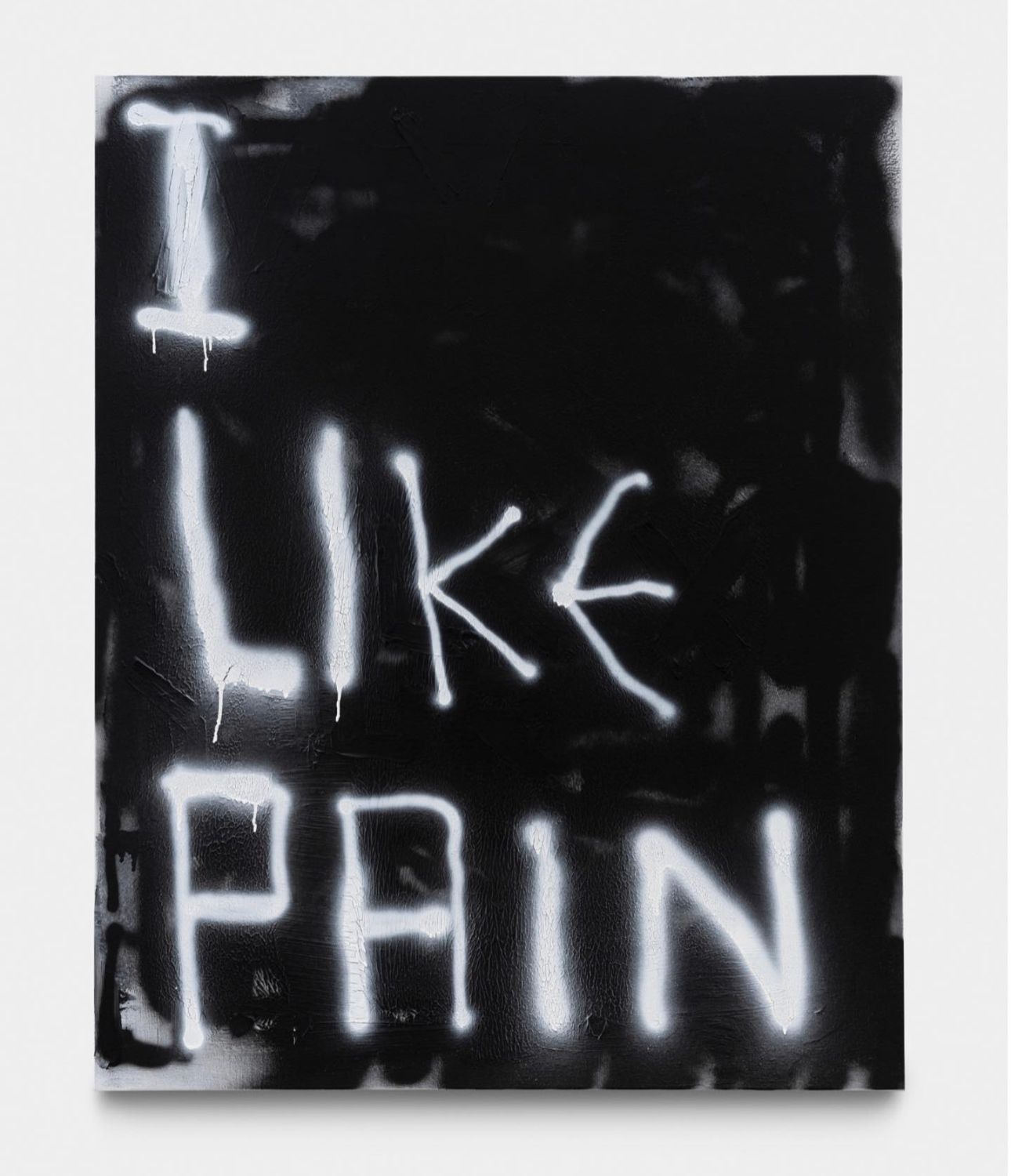

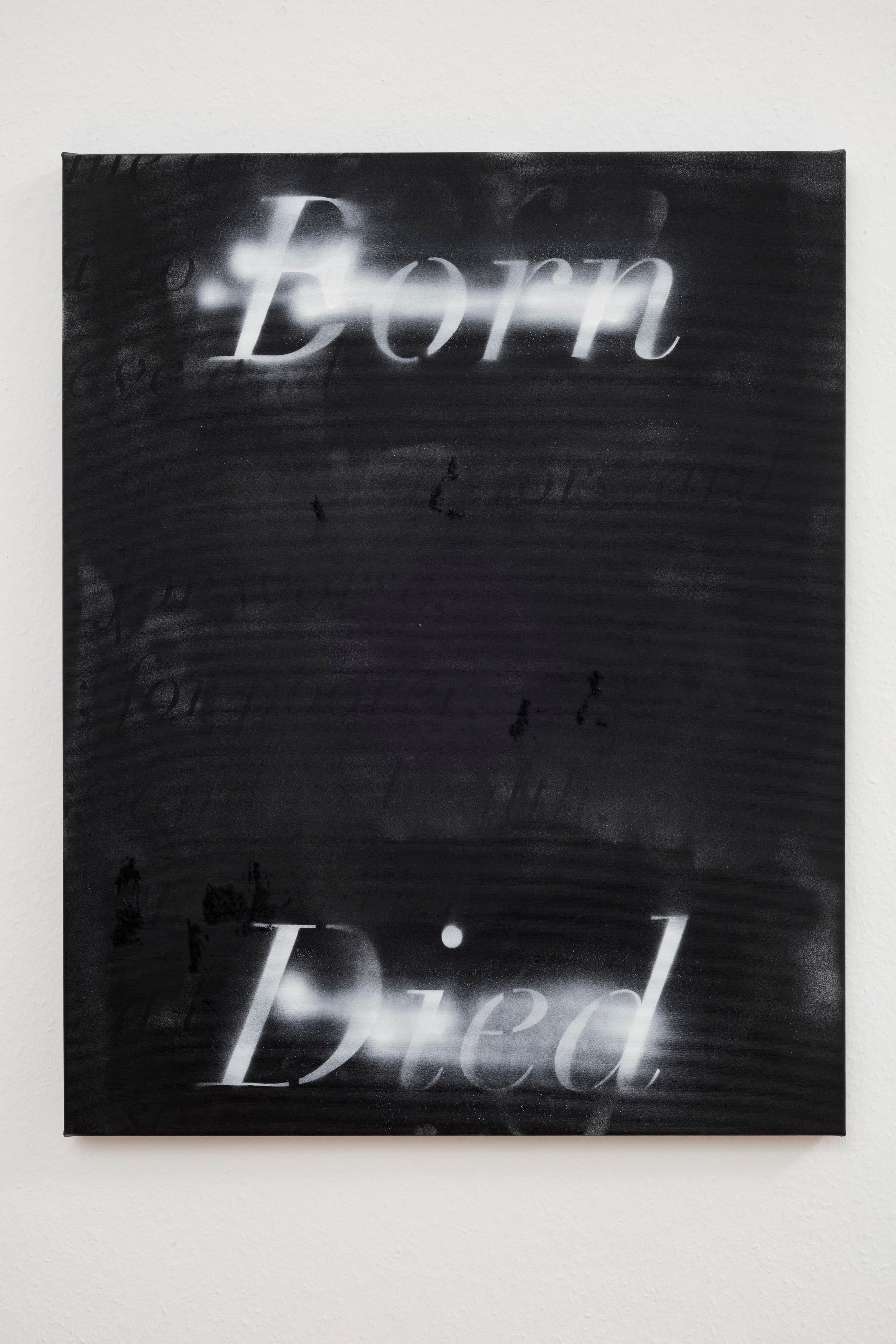

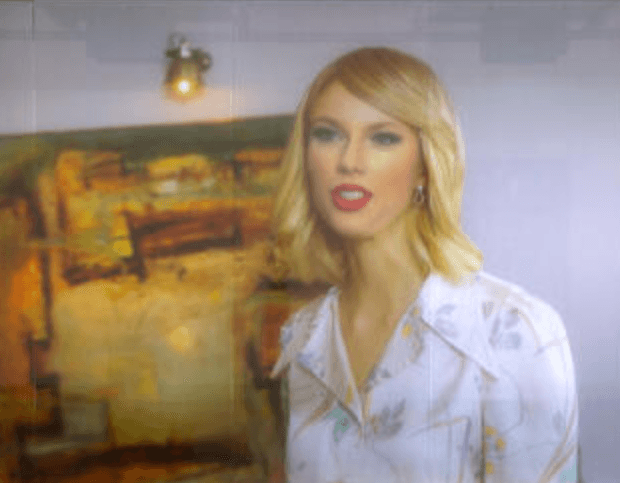

Most known for his text-based paintings, artist and musician Richie Culver presents language that’s more familiar from the world of memes.

With phrases such as “I miss French kissing American men in German night clubs,” “I Wanna Do as Little as Possible But Still Get That Mad Money,” and “I was not born to work hard” painted over monochrome canvasses or repurposed cardboard backgrounds, Culver examines the intersections of class, masculinity, digital performance, and that impossible edge between sincerity and irony that exists online.

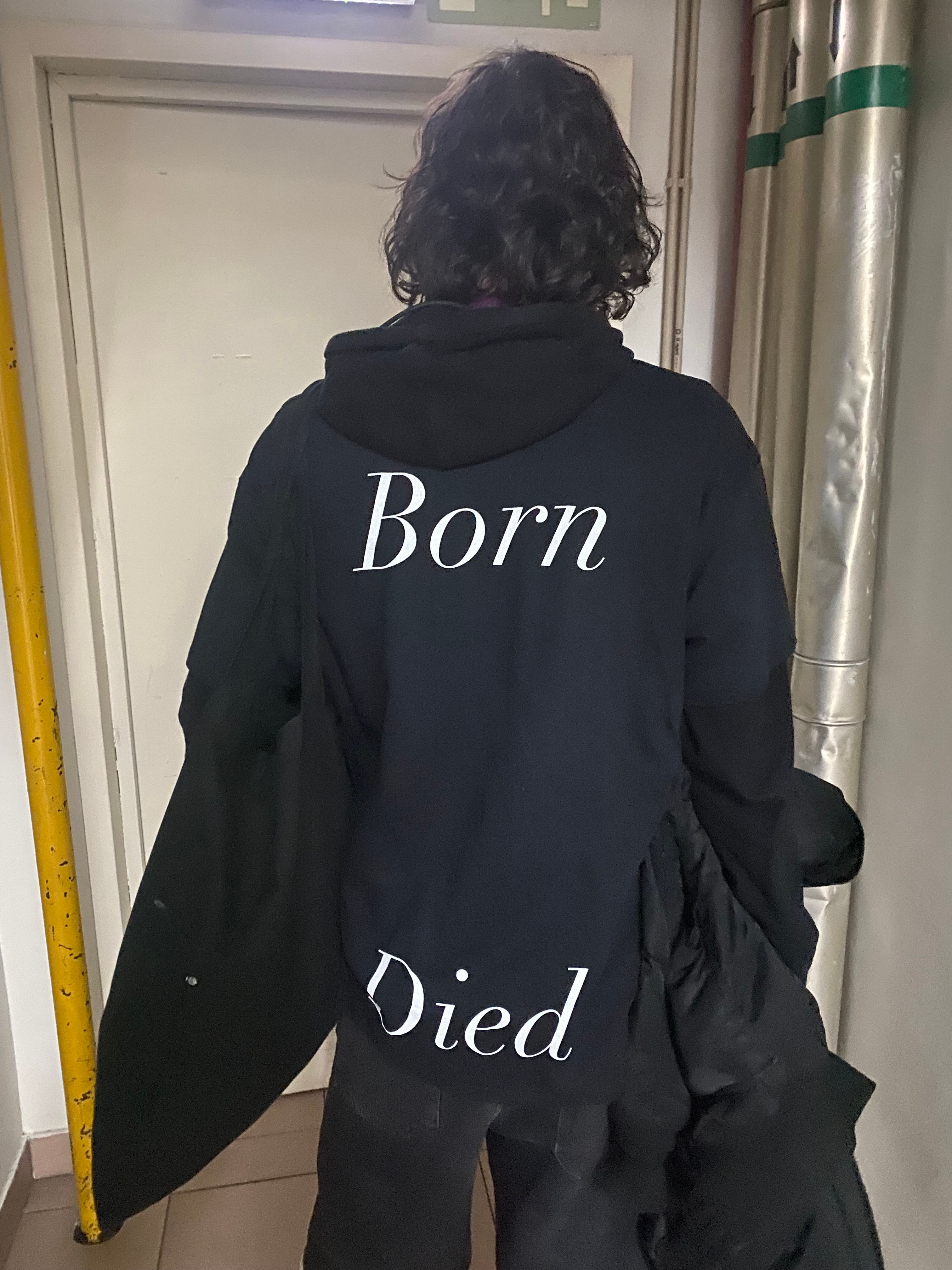

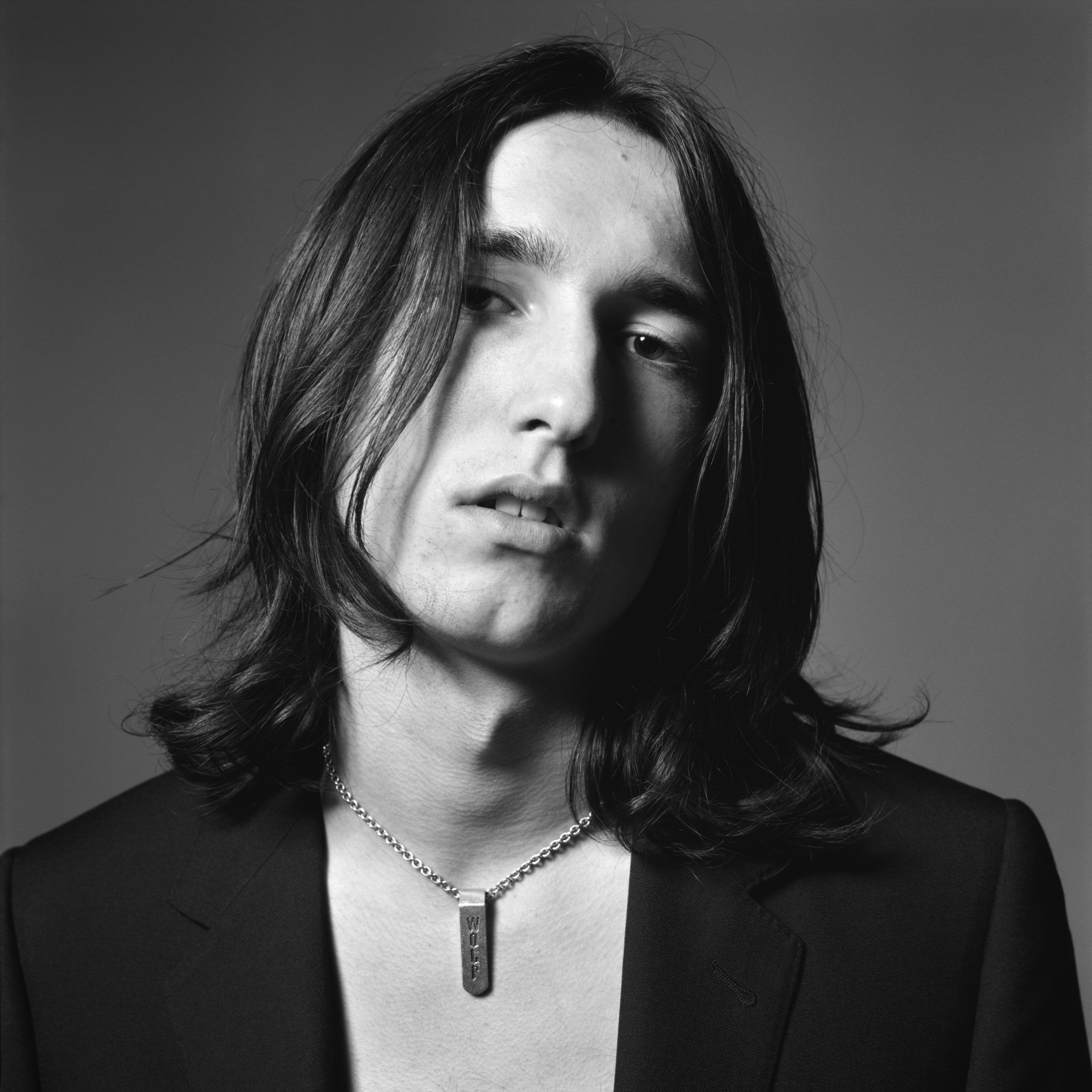

Out on June 14, Hostile Environments is Richie Culver’s self-produced, self-written, and self-released follow-up to the 2023 album Scream if You Don’t Exist. It is a subtle departure from the malaise and disquiet that typically punctuates his ambient medleys of hip hop, spoken word, noise, and samples of isolated industrial sounds. The album explores the tense states of optimism and dreaminess, nostalgia and dread, imagination and abyss that accompany a version of himself that never left his hometown. Born and raised near Hull—the same port city that birthed Genesis P-Orridge and Cosey Fanni Tutti’s performance art group COUM Transmissions, which would later morph into Throbbing Gristle—Culver developed his own practice, and it was initially furnished by the history and mythos of Hull's own avant-garde past. But in the last few years, Culver has expanded. He has collaborated with musician and dancer Blackhaine, had shows at Vienna’s Galerie Kandlhofer and London’s Carlos/Ishikawa, and even had one of his paintings plastered across a collection of Drake merch.

Before the release of Hostile Environments, Phillip Pyle spoke to Culver about the power small towns wield over their inhabitants, “drowning in the English language,” and reconciling the poles of his music and visual art practices.

PHILLIP PYLE: The press release for Hostile Environments explains that you explore “an alternative reality” on this album where you were “never able to escape the constraints” of your past. What are these constraints, and why did you decide to revisit the past now?

RICHIE CULVER: I’m definitely focusing on the past with my music—and maybe with all of my work. There’s not much to pick from within fatherhood, and the kind of normality that my life is now with three kids. I don’t drink, I don’t take drugs, I don’t smoke. I’m as boring as it can be. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

To answer the question, I’m working backwards, and it’s taken a long time to get to where I am now, on a personal level, a work level. So, I’m going back to that classic Tracy Chapman “Fast Car” concept which runs through the album.

PP: “Slow Car” is a riff on the painting Small Town which you made in response to “Fast Car.” What drew you to “Fast Car” as a starting point?

RC: It’s probably in the top hundred of best pop songs ever written. I remember driving into the local town from the seaside village I’m from and it playing on the radio. It was one of those moments before—I must have been seven or eight—I started to understand the components of songs and that endorphins were circulating in my body. I was tuning into something. Then, with the lyrics—”Leave tonight or live and die this way”—I was thinking, is that me? You know those core memories that we have as kids? That was definitely one of them.

So, fast forward to making this record. It’s the most listenable record I’ve made but it still sits in the experimental world, and I was aware of positioning a pop song within the music world I inhabit. It was a challenge for my own ego to make an experimental record that’s loosely based around “Fast Car.” But, when something is so ingrained in me, like that song is, I don’t care, I’m going to go with it. The track and the whole record are about not leaving tonight and living and dying in that way—and staying in the small town, and the freedom that comes with giving in rather than constantly trying to fight to better yourself and this drive that most artists or creatives have. To be okay with normalness, which is something I’ve always fought against.

PP: That song always had a very American undertone to me, so it’s interesting to hear that it also translates to an English context.

RC: One hundred percent. There was always that other layer, of my obsession with America while growing up and everything being better there. Everything was bigger there. Everything was cooler there. In this small town in England, I always felt a million miles away, but that’s—without sounding too cheesy—the power of music.

PP: Speaking of your hometown, Hull, you’ve previously mentioned that Genesis P-Orridge is a major influence for you. There’s a similar mobility between media in both of your works—and a shared deconstructive approach to language, sound, and images. What does P-Orridge being from Hull mean to you?

RC: That was huge. I was working in a caravan factory when I first left school, and I would go partying on the weekend. I’d already been exposed to rave culture, free parties and everything, then it moved into warehouses and clubs in and around Hull. I found this new level of education at after parties because I’d meet people that lived in bigger cities, such as Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield, who’d come to study in Hull.

One time, there was a Larry Clark book on the table, and I started looking through it and my mind was blown away by these photographs. Later, on that Sunday afternoon or Monday morning, I got exposed to Genesis P-Orridge and Throbbing Gristle. The student was like, “You know they’re from Hull?” Instantly, I was like, “Oh my gosh,” there was something extremely experimental here… It was like, well, you can do anything! You can stab a drum. Anything. That was industrial music that I was exposed to, and I’ve ended up coming back to it.

I think we [P-Orridge and I] have similar tones in our voice. I have a few of their polaroids that I got from no gallery in New York, which I treasure. It’s another deep one, knowing there’s that history of real underground culture that was happening once in Hull, this town where there’s rugby, soccer, football, pubs, and fighting. I like to walk the streets when I go back and feel the ghosts of that era that I never managed to be in. Hopefully, there can be a new little input of the avant-garde through my music and stuff.

PP: You’re quite prodigious in terms of the sheer number of paintings and projects that you release. Yet, you also have these critiques of labor embedded in a lot of your paintings. You have quotes like, “Find a job that you love and you will never have to work another day in your life” or “When your hobby becomes your job, get a new hobby.” What’s your relationship to labor and work as an artist?

RC: I’ve been a self-taught outsider artist for the last 10 years. It was like a scratch that I needed to itch. I’d speak to collectors or gallerists. “Where did you study?” always came up, and I would be like, “Okay, I didn’t.” Last year, the Royal College of Art offered the masters course for one year, so I did it. I now have an MA in painting.

Like most artists, I’ve always felt like an outsider. I don’t go to any openings, I’m not part of any scene or any movement. I still feel like that kind of person. When I walk into a record shop or into a fashion store, I always feel less than. I walk in feeling they think I’m going to steal something. It even feels worse now that I have an MA. I guess it’s like that loving hug from a father figure that I’ve always wanted. I thought that I was going to get it from the art world—but it’s such a cold, void-like world and industry, like them all.

It feels like my hobby has become my job but there’s still a massive hole within me and I’m not sure what’s going to fill it. It comes back to wanting that mentor or loved one to say: “You’re doing good. You’re going in the right direction.” Growing up without a dad—not to get too deep—I’ve dragged that into my work practice. I’m wanting someone to say, “You’re doing okay,” and it never seems to come. So, I’ll keep moving from discipline to discipline.

PP: With these movements, you’ve mentioned before that wordlessness is an end goal of your painting practice. Do you feel the same way about your music? Would you like for it to become entirely wordless?

RC: I think that’s why I started the Quiet Husband project. I was drowning in the English language in my text and my visual stuff. Then, in my music, it was just constant words. I wanted to come back to the noise thing. The Quiet Husband project has been the vehicle for that, to a different layer of my practice under a different name that I’ve always wanted to use.

However, words are my thing now. Text will always be the start. Words and poetry, language in one way or another. I guess the goal would be to be an abstract painter, but I’ve kind of made my bed with the words.

PP: You’ve also been quite critical toward figuration, at least in relation to the art market. One of your paintings states: “Paint like you are poor. And if you are poor, paint figurative.” Then, on your story last week, you posted, “Imagine a world where figurative artists are posting for ceasefire.” How do you position your work in relation to figuration?

RC: I wrote the figurative piece before I went to the RCA. I was looking from the outside into the art market at this figuration boom that’s never seemed to stop.

I recently did these World War II plastic surgery patients and I’ve called them “Disfiguration.” It’s from the early stages of plastic surgery. That’s what I’m working on in the studio at the moment, so there’s figuration in there but I’ve tried to twist it into disfiguration. I’m trying to work on new languages.

PP: In your painting practice, you often use the word “I” or appropriate direct messages or Instagram comments into your works. How has the position of the self shifted over the course of your music and art practices?

RC: Well, the music is all autobiographical. Within painting, there’s more of a voyeurism and it’s not necessarily connected to me. “I” does come up quite a lot, more in my visual stuff. But, again, there’s a dual purpose going on—maybe there are two “mes.” There’s the me that stayed in Hull that I write about in this record, and there’s the me that’s living this very different life in the art/music world in London, in the capital of England. I can always flip back to that person, the inner child feeling less than and the persona of the artist that doesn’t ever seem to feel like it can all be taken away.

You’ll know what I mean if you’re from a small town. Family members who are like, “This art stuff, this music stuff—are you still doing it?” These kinds of questions. There’s a little part of me, when my mother gives me a certain look, that still now, at this age, can shrink to this kid… That’s why I struggle going back. When somebody critiques my work in the art world, I don’t care, it brushes off me. But if it’s from my hometown, instantly I can feel this, “Oh my god, who am I kidding? I’m not kidding anyone. I am a joke and shouldn’t be doing this.” Hometowns have such power over people from what I’ve seen. I’ve seen it in friends when I go back, or even loved ones. You see them shrink to this 13-year-old. There are all these ghosts and memories hanging around. It definitely translates into my practice. You can fool everyone, but you can’t fool your hometown.

PP: You describe this album as a “love album.” Is it a love album between these two versions of yourself that you’re talking about, or perhaps a love letter to your hometown?

RC: Possibly sonically. This [Hostile Environments] has much more of a melodic, K-holey, loopy kind of thing. It’s much more optimistic. Even though the core of the album is about being trapped and surrendering to not moving, the outer layer is quite dreamy. It feels like somebody else has made it. That’s why it was important for me to do it all on this one. I wanted to challenge myself to do everything. It’s interesting that it’s turned out to be a more optimistic sounding record than the rest.

PP: There’s an anti-art and sometimes meme-like sentiment in your visual practice. You’ve used the guy in the corner of the party meme and phrases like, “YOLO Then u Die,” which is also the title for a song on Scream if You Don't Exist. However, generally, your music—while you do appropriate some text from your paintings—leaves much less room for internet and meme-y rhetoric. It feels more grounded in a way.

RC: That’s my biggest fight at the moment. You’ve touched the soft spot. There are not many visual artists I’m looking at who are doing both. It’s like I have an umbrella that is all of my work. And it comes back to the drowning in text.

At school, I would avoid getting bullied and having problems at school via comedy. That was my pass through high school. I was okay at soccer and whatnot, but it was still a rough school to navigate. My go-to when things get tough is to bring that out, to take the piss out of myself. With my music, when I started writing it all after the Blackhaine record in 2021 (“Did u cum yet? / I’m not gonna cum”), I realized there’s no space for that. If I’m going to make this music, and I’m going to tell stories autobiographically, there would be no jokes in it. If I’m going to do this from the heart, then it has to be kind of harsh and relatively morbid. My reaction to life, throughout situations, has always been to not face them and to use humor. Now, after the Royal College MA, I need to move forward with my visual practice and lose the words a little bit because my “Get Out of Jail Free” card is to always poke fun and be meme-like. I don’t mind the contemporary language, it’s a nice platform to work from, but I think it may have come to an end.

Credits

- Text: PHILLIP PYLE

Related Content

Blackhaine: Harsh Realities

A Bad Night’s Sleep with Sega Bodega

Who the fuck is Vaquera?

A Specialist in Club Music: VTSS

Taylor Swift Is A Virus

When Metal Triggers Catharsis: Lord Spikeheart

Caviar, Leather Pants, and Metamodernism: Bands discuss HEDI SLIMANE's Portrait of a Performer for CELINE

Human After All: Finding the Others

HR GIGER & MIRE LEE: Horror, Slime, and Satanic Eroticism