When Metal Triggers Catharsis: Lord Spikeheart

|HARRIET SHEPHERD

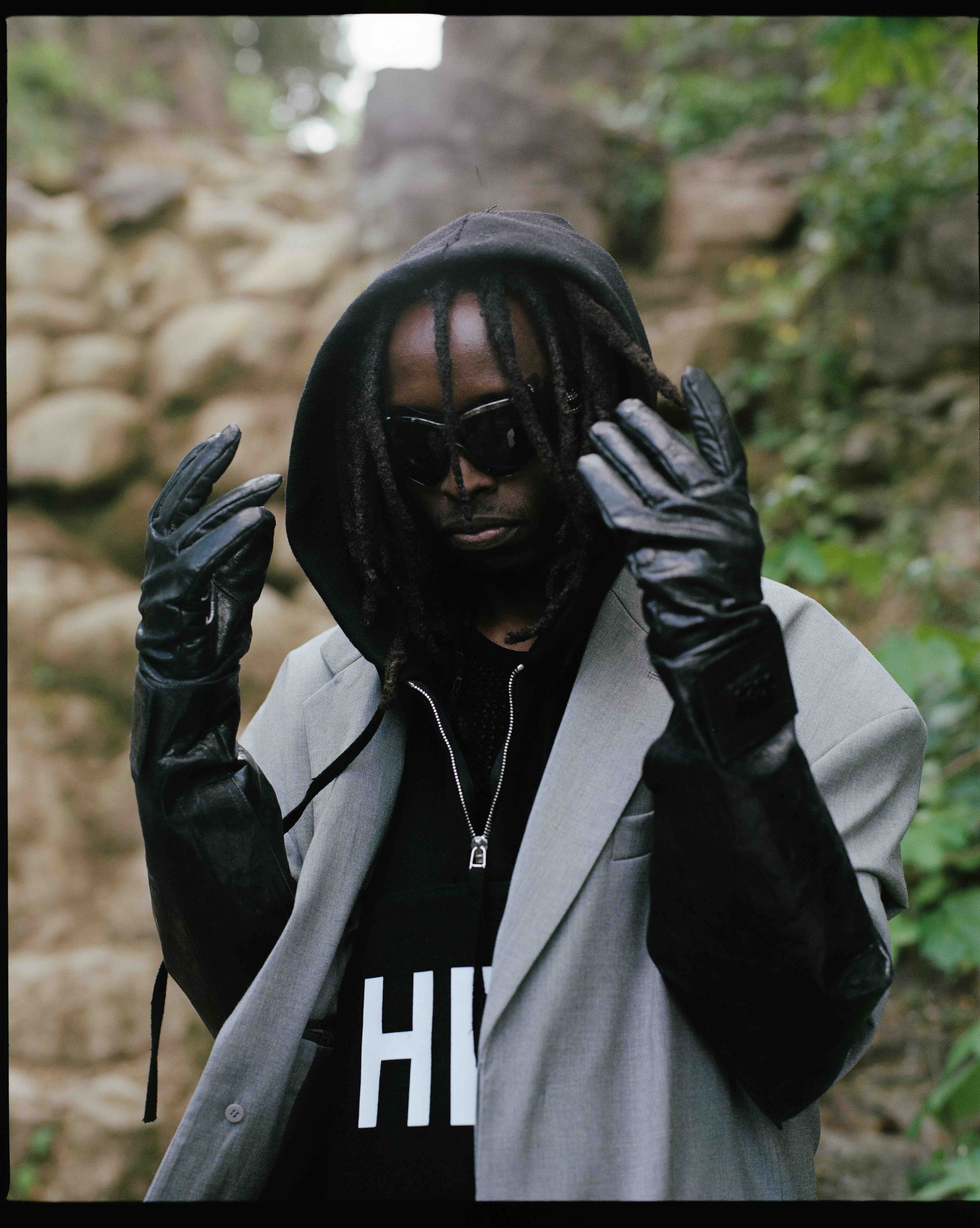

In hardcore lore, it is written: “Metalheads are nice people cosplaying as mean people; hippies are mean people cosplaying as nice people.” Slashing guitar riffs, flaming skulls, and guttural screams may intimidate some, but for Kenyan hellion Martin Kanja—aka Lord Spikeheart—metal has always been “wholesome.”

Born in Nakuru, Kenya, Kanja moved to Nairobi in 2010, metamorphosing into his thorny moniker amid the mosh pits of the city’s underground metal scene. For the 19-year-old Kanja, “raging” was not an act of teenage fury, but one of cathartic release. “It was very uplifting—there’s no room for negativity in that moment.”

Since then, Kanja has played a propulsive role in shaping East Africa’s metal scene as part of a hefty trifecta of bands—Lust of a Dying Breed, The Seeds of Datura, and most recently the front man of now-dissolved grindcore duo Duma. And just two years after the latter’s eponymous and critically-acclaimed album was released, Lord Spikeheart has struck out on his own—with an incandescent debut, and the launch of his own label dedicated to the “heaviest and darkest sounds on the continent.”

Technically, Kanja might have gone “solo,” but The Adept is a product of collaboration, uniting an international roster of multi-genre bass-shredders that includes Brodinski, Backxwash, and Scotch Rolex. The result is a matrimony of extreme metal, breakneck trance, industrial abrasion, and hellish rap, that, beneath its sonic chaos, is underpinned by Spikeheart’s endearing optimism. The album’s opener encapsulates its essence—hurtling into the punishing percussion and static distortion of “TYVM,” pierced by the graveled screams of polite niceties: “thank you very much.”

Dedicated to his late great grandmother—the only female Field Marshal in Kenya’s Mau Mau uprising against British colonialists—Kanja sees The Adept both as a tribute and a beacon of hope in the ongoing fight against oppression. The album also marks the inauguration of HAEKALU (“temple” in Swahili), the imprint Kanja now runs with his wife from their home in Kampala, Uganda. Committed to creating vital infrastructure for its artists, HAEKALU acts as a meeting point for like-minded metalheads and a platform for repopulating the canon of metal with those overshadowed by Western cultural dominance.

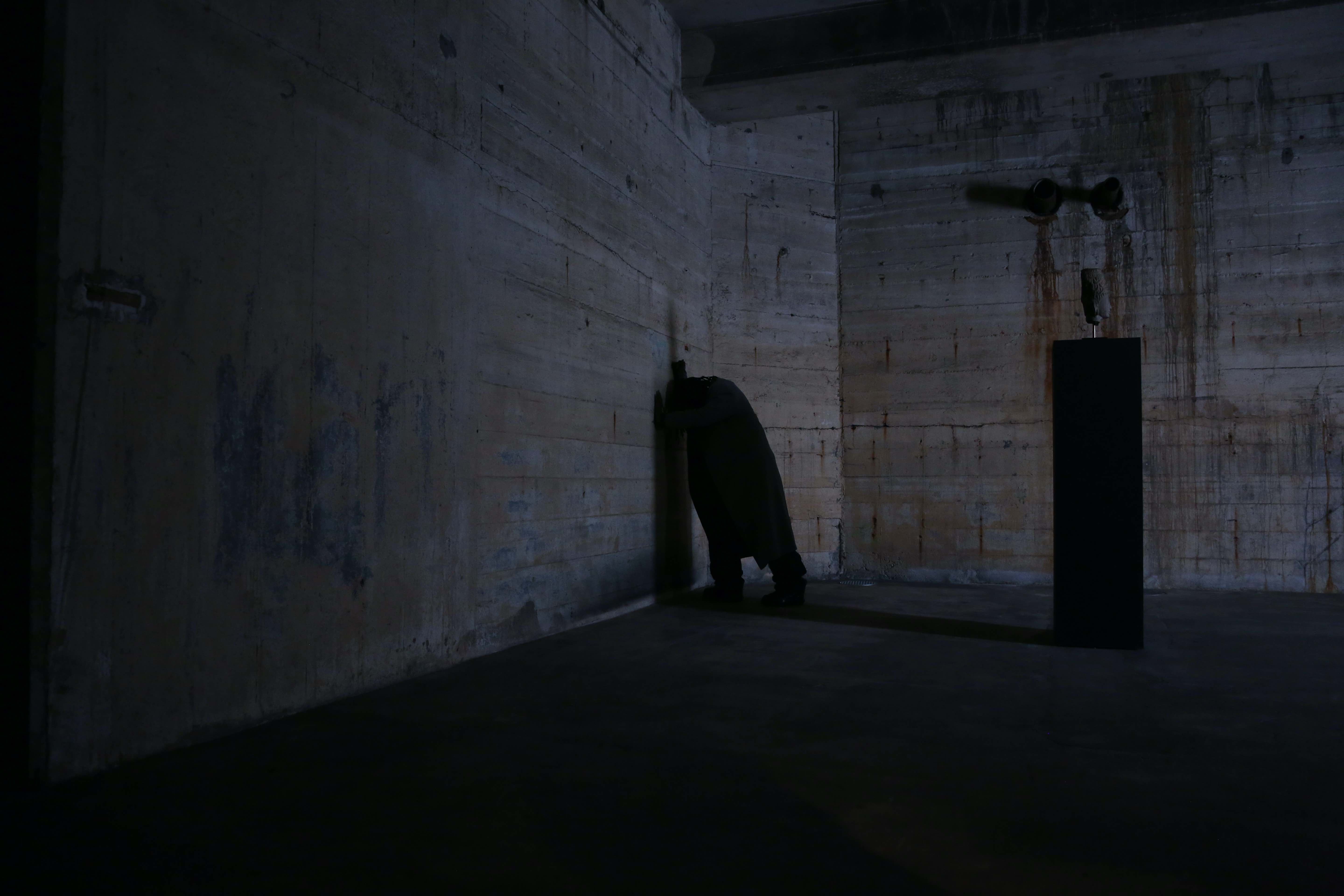

Embraced by institutions like the Venice Biennale and Salone del Mobile, Kanja now wields his amplified platform to dismantle the Western-centric narrative of metal music. This defiance is mirrored in his album’s striking artwork, which incorporates Max Pinckers’ re-enactment of the burning of Kenya’s colonial archives—a rejection of imposed histories and reclamation of cultural identity. Through HAEKALU, Lord Spikeheart cultivates fertile ground for a new generation of African metal artists, illuminating untapped sonic power. The musician was photographed at his favorite hangout spot, the Feuerle Collection—a private art collection with a focus on international contemporary and Southeast Asian art and Chinese design.

HARRIET SHEPHERD: Lord Spikeheart is an incredibly evocative image in and of itself. What’s the story behind it?

LORD SPIKEHEART: It actually started as a joke… I used to have very spiky hair, so people called me spiky. Everybody in the scene had weird names—Rock Spike or Death Girl—and I stuck with it because I couldn’t think of anything else [laughs]. In Africa, plants with thorns and spikes have medicinal qualities, they protect something important.

HS: That’s very wholesome for something that conjures such a tragic, romantic image. Metal has historically trafficked in extremes, both in terms of its sonic assault and graphic imagery. Were you always drawn to this kind of intensity?

LS: Definitely. I used to read a lot of gothic literature, like Edgar Allen Poe and Dracula. I was listening to a lot of rock and roll back in high school, but when I found metal, I was so comfortable. I loved how it was so intense. And the people involved are very nice people. That kind of drew me in, because I saw that metalheads are really cool guys who were using this dark imagery to mask how nice they are. We’re a very small community, and it’s really a lifestyle. I found that it was not happening in the reggae scene or the pop scene. Metalheads are really like 24/7. It’s not a joke.

HS: I read an old interview from your days with Lust of a Dying Breed, where you referred to Africa as “the most metal place on earth.” You were talking specifically about how it’s portrayed in international media. Do you think that perception has evolved?

LS: In Africa, things are very different from places in Europe. People are living below the poverty line, the transport systems are messed up—people are really stuck, because there are no tools or resources for them to move around and gain experiences in the world. That metal energy has always been here; diehard fans have existed forever, but the international representation was not—and that’s what makes it sustainable. It’s very important, I think, to show people from where I’m from that the world is huge, and experiences can be different. To show them that somebody from here can push this thing and it can be successful. As soon as you change your paradigm and your mindset, things start rolling. It’s like a domino effect.

HS: That’s a big part of the founding mentality behind HAEKALU—to be able to achieve that. When did the idea first come about?

LS: It had been brewing for some time. It was 2015 when I first realized we needed a record label that actually protects us. I called a meeting with all the bands in Nairobi, and we sat down in the park, talking about how we could make a studio and a label, but nothing ever materialized. When I went to Uganda and formed Duma, that’s when I saw how it works—what follows after you release the music, and how you can push a band. I saw how you do distribution, publishing, marketing campaigns, and tour management firsthand. This is information that most musicians and creatives in Africa don’t have. I saw that establishing a record label that actually gives artists the tools and resources to push their art into the market was very important. I felt like this was the right time for it.

HS: How important is it that your label is African owned? It must be a different thing to be in a position where you can do that kind of homegrown work and put people on in that way.

LS: It’s very necessary. We are often told we cannot make it without the external help of white hands, that we owe people for our own skills, abilities… Even the album artwork [taken from Caravaggio’s Crowning with Thorns, depicting the mockery of Jesus being crowned with thorns for the crucifixion] reflects my personal experience as an African artist against cultural colonialism. Just like Jesus, I wanted to prove all these voices wrong with this record: you can make it, stand out, and come back as the king of kings.

HS: There’s a lot of Christian imagery in your music. Metal is often dismissed or disparaged for being satanic and ungodly—what’s your relationship to spirituality in your sound?

LS: I come from a very religious background. My mum runs a church. When I was small, me and my brother read the whole Bible, back to back, start to finish. I was like, “Damn! This is crazy.” It’s very brutal. I love the imagery in the Book of Revelation—it’s very metal what’s going on in that book [laughs]. I studied Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity, and I saw that they all have the same kinds of concepts behind them. This kind of sound has a powerful energy, and I saw it as a good channel for spirituality. I saw that, in this music, the sound itself, and the textures it has, are even more profound when a higher creator is involved—not a God, but the human soul itself. For me, the main thing is to uplift the consciousness of the listener through my music and use its frequencies for people to accept themselves for who they are; to love themselves, and to have less fear taking risks, because they’ll be ok whatever happens.

HS: Your work has always encompassed visual worldbuilding, and in this release, that’s manifested in a collaboration with NMR.CC [the Athens-based design studio responsible for Travis Scott’s Utopia]. What was the starting point for The Adept?

LS: The whole vibe for this record was collaborative. The visuals go together with the music—they make it more profound. I wanted people who would make something new, something authentic. As the record is not totally metal but a hybrid form with elements of trap, hip-hop, trance, techno, and ethnic, and exploring themes of spirituality, psychedelia, and rebellion against oppression, I wanted all my visuals to reflect a new aesthetic: sober, classy, dark, esoteric, and most of all African. Something different from the typical metal imagery. I want to create realms and dimensions and worlds. And this has to translate in the videos too, to translate the sonic landscapes that are in the album. So, every video is about projecting this image of a New Age God, in this modern world, from the ancient world...

HS: Your imagery plays a lot with the concept of land and ownership…

LS: Yeah, exactly. It’s all about giving back power to our people. I wanted to represent my connection with my land, with the nature and soul of the continent. I refuse the hype representation of the African artist coming from the slums or ghettos—it does not represent me at all.

I also wanted to create something that really captures you, like watching a movie. It was very important to have a dynamic and diverse visual representation, not like this traditional thing of a band in some room with a strobe and some smoke…

HS: You have some smoke too!

LS: [Laughs] Actually, we just found that smoke on the road when we were shooting the video. We were driving by as people were burning this garbage and grass. It was about to rain, so we just stopped the car and filmed it in a few minutes before the rain came down.

HS: You’ve talked a lot about your entrance and affinity to metal subculture, but your work has been a hybrid of a lot of electronic music as well. Where did that influence come from initially?

LS: It was out of necessity. When I quit the corporate world, I was stuck in Nakuru, where I was born. Me and my friend Leon [Lust of a Dying Breed] had no money, no band, just a room with a couch and a laptop and a microphone. He had this software, so we had to make everything electronically. We made these helicopter chopping drums, very quick drums, and really high pitched “neoowww” synthesizers, and I put vocals on it. We made this song called Brothel Hell. That’s the first time we saw that you can go dark as hell and put a whole band in your laptop.

HS: Your grandmother inspires the album and is dedicated to her. You’ve said in previous interviews that you grew up without giving much thought to her role in history. When did you start to reframe that, and how important was that for your creative process?

LS: I didn’t really understand that the world is messed up until later. I see what’s happening everywhere now, and it’s the same thing my grandma was fighting back in the day. What she stood for, and how they put their lives on the line for millions of people against oppression and people being killed. Since I’m grown, I realize that the world needs such people. People who decide to be the voice of the voiceless and stand against these oppressive entities and powers that just want to manipulate and control everyone. I was supposed to take a family picture with her and my wife for the album, but she passed away last year before we could do it. After she passed, I was like, “OK, now we really have to impress this vision on the world, and make sure her name isn’t forgotten.” It was a way to say thank you for showing us what actually matters—people matter. It’s all about love and community and being together as a community. That’s why the album is dedicated to her. She showed me you can be successful in whatever you do. They stayed in the bush for 11 to 12 years with no clothes and wearing animal skins, they became like animals at some point. They smelt like animals, talked to animals. Even after the war ended, they didn’t believe it, they were still fighting. We can’t just let everything sink to destruction and despair. We need these kinds of entities giving hope and encouragement to the weak, and to the ones who need it.

HS: Clearly that message is resonating.

LS: The world has just been getting trippier and more extreme. There’s a lot of tension in the global arena. There are wars happening—in Africa with Sudan and Benin, and it’s easy to get drawn into this energy. You need to accept it—it’s there, it’s dark, it’s heavy. But release is very important. Metal takes that energy and alchemizes it into something positive that brings people together, because it really has this dedicated worldwide community. Metal is the most extreme music you can get. And it feels even more relevant because it feels like a way of transmuting all this darkness that’s happening in the world into something relatable and expressive, and uplifting.

HS: There’s something very cathartic about the experience of even seeing you perform. How does that intensity translate for you?

LS: The first time I performed I was seven years old. My mom took me to this small music festival when I was in kindergarten. I’m chasing that high to this day.

HS: What was the performance?

LS: Oh my god [laughs]. It was like this traditional dance. We were in a circle, dancing and singing together like kids do. I think I came in fifth place. And they gave me chocolate. I was so happy.

Credits

- Text: HARRIET SHEPHERD

- Photography: ALMA LEANDRA

- Fashion: KAMAL EMANGA

- Talent: LORD SPIKEHEART

- Light: LEO SCHINN

- Photography Assistant: JOHANN KOHLHOFF

- Special Thanks: THE FEUERLE COLLECTION

Related Products

Related Content

Legion of DUMA: Nairobi’s hardcore duo premieres a new video

Gated Nightmares: Herrensauna’s Cem Dukkha

Drain Gang

“Punk Metal, Babes”: ENRIQUE AGUDO Explores Identity, Sexuality, and Mythology in VR for a Digitized Tribeca Film Festival

STILE DUCATI: The Anatomy of a Speed Aesthetic

Why Not End It Here, Right Now: HIDEO KOJIMA

VIRGINIE DESPENTES: Hates People, Loves Dogs.

“I Don’t Want Anything”: An Interview with ECCO2K