A Reality TV Star as President: Marco Brambilla

|Claire Koron Elat

“We’re living in an age of spectacle, both in what we consume, and in hard news," says artists Marco Brambilla.

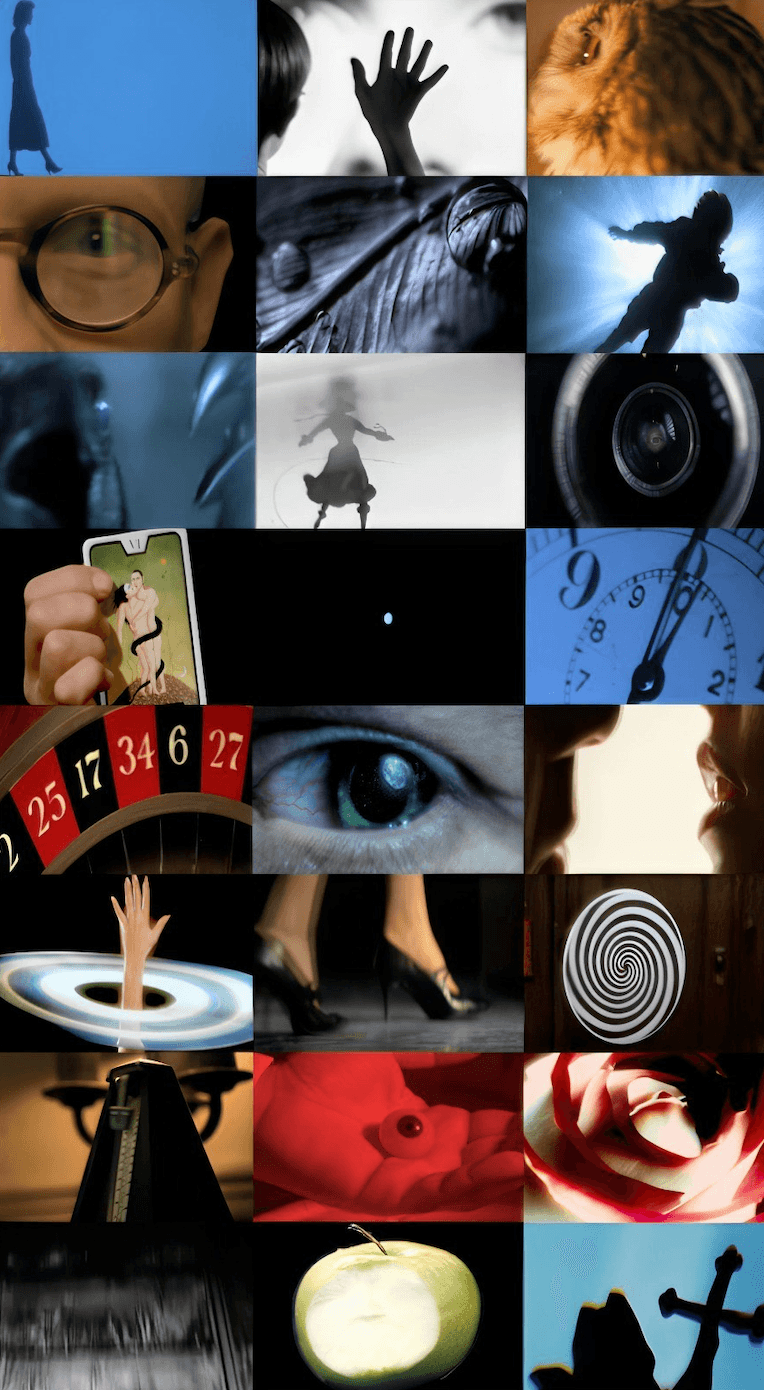

Desire, Marco Brambilla

Curated by Jérôme Sans, Brambilla’s most recent exhibition “Altered States” at Golden Goose HAUS in Marghera (Venice) explores the space between dream, memory, and media through surreal image worlds and soundscapes that let memory, fantasy, and desire collide.

For HAUS Week, which coincided with the opening of the Biennale of Architecture 2025, the brand opened the doors to HAUS with 032c hosting three different panel conversations, exploring themes based on Brambilla’s show narrative with the panelists Dan Solbach, Allan Arma, Gustave Rudman, Federico Sargentone, Hella Schneider, and Marco Neroni.

In this interview, Brambilla discusses how a reality TV star could become president, our superficial understanding of the world, and working on Hollywood productions vs. art exhibitions.

Marco Brambilla, Courtesy of the artist

Heaven's Gate, Megaplex Video Series, Marco Brambilla

Claire Koron Elat: Your work is interested in the notion of the spectacle, and perhaps even how the spectacle has taken over—for example in cinema. How do you perceive the development of fashion having become entertainment and where do you see the parallels to the evolution of cinema?

MARCO BRAMBILLA: I think it’s very similar to what happened at the turn of the last century in theater, where, rather than putting on plays that had to do with dialogue and characters, they were setting fire to some stages and creating a visual spectacle for theater. And spectacle also makes it easier to make more material, because you don’t need the kind of attention to detail or talent that you would when developing an original work or that has more plot and story development.

So, it’s a very easy way to create material and product. If you’re looking at mainstream cinema as a product, the spectacle is a very effective way to grab people’s attention and to give people enough stimulation to keep them coming back without having to dive too deep into the meaning of things. And we’ve set up distribution systems for that kind of communication to work really well.

The concept of spectacle becomes appealing and important if you consider that people have shorter attention spans today. Look at the news cycle and the way the news is fed to us in the kind of 24-hour news reporting system—no matter whether it’s about a war, who the new pope is, or the presidential elections. It all becomes this constant cause and effect that you get people to comment on, and that creates more content.

So, we’re living in an age of spectacle, both in what we consume, and in hard news—even information that affects our lives is communicated in a very spectacular way to break through the noise. The problem is that it creates a threshold of noise that gets harder and harder to break through.

Flashback, Marco Brambilla

CKE: Would you say that people putting out creative work today are less talented because you need to pay less attention to detail?

MB: No. I think what it forces you to do is take the media landscape into account. It’s not enough to just make the work. You have to take the way the work will be perceived into account. Everything has a kind of meta meaning to it now, which becomes part of the communication of your idea as well. I think it is usually more compelling if work connects to the present day.

CKE: Why do you think there is the need to present news as a spectacle?

MB: We’re much more voracious with regards to the amount of information we consume every day. Entire events are communicated so that people can go through the global news in 15 minutes as a series of soundbites. I think it gives you a very superficial understanding of the world. It gives you the illusion of being connected to everything.

CKE: You can also say that fashion shows have become a form of cinema. Where do you think the line blurs between fashion presentation and film production?

MB: I think there’s a trend. I’m not involved in either fashion or film anymore, but as an artist, I can say that there’s definitely a transaction of image between those worlds. You see a lot of science fiction films that draw directly from collections as inspiration for costume design, because fashion has become so experimental that it can seem as if we’re looking into the future.

CKE: Given that your work also investigates Hollywood, there is a close tie to the American Dream and its promises. Do you think the American Dream still exists?

MB: I think it’s shifted. The mainstream American dream has become more superficial than it used to be let’s say in the 60s. Back then, America had high aspirations like the space program where they were landing men on the moon. Now the American dream has shifted into a financial and visibility model. What is now considered most aspirational is fame and fortune. But I think that quickly becomes an empty promise. Perhaps there is a tipping point to the American dream, and there’s a rebirth that will stem from that. But I think it’s the way empires collapse. Excess is unsustainable by definition.

Celluloid Dorthy, Megaplex Video Series, Marco Brambilla

CKE: Do you think we’re already at this point of collapse or when do you think we’re going to reach it?

MB: I don’t think it’s finite. It depends on our capacity to consume this kind of dialogue and to buy into this kind of lifestyle. Maybe it’s cyclical. For the next generation, my son who is 20 for instance doesn’t respond to it. They’re not on Instagram or other social media platforms because they don’t consider those ways of communicating to be authentic. So, there may be hope that this generation may reject a lot of what’s been sold as a dream. And maybe their dream will be different; more substantial and authentic.

CKE: You’ve also produced a few movies that were Hollywood productions. What are the differences between making film and producing an art show and what do you enjoy more?

MB: I’ve always been a filmmaker, basically since I was 14 years old. I made more experimental films when I started, then I made commercials, and then I branched into Hollywood. And then I came back to a much simpler kind of experimental, more subversive way of telling stories, which took me back to my art practice. The one thing that’s remained consistent is I’ve worked as an image maker dealing with the moving image. But I now have more agency over what I’m making and have more opportunities for self-expression. From that point of view, there’s really no comparison between being a director on a film, especially a studio film. It has very little in common with making an artwork. I find self-expression to be the most satisfying part of working as an Artist.

CKE: Are there more constraints when you work on a film production versus an art show?

MB: You have less constraints financially but many more constraints creatively.

CKE: With the extreme image saturation that you reference and also incorporate in your work, how do you personally consume images on a daily basis?

MB: I’ve actually gone back to analogue. I like to look at books and sit in the library to do my research. Of course, we do research in my studio. I have people who do research online, and I have people who work in AI to create experiments and presentations. I don’t personally like to work directly with AI. In terms of just having a very pure creative impulse, I think it’s better to refrain from a constant feedback of referencing something or being fed more references. I don’t think it’s a very good way to create original material.

It’s much better to dream on your own. You’re obviously influenced by things you see. But I think the frequency at which you see things in the digital world is so extreme that sometimes you never get the chance to really find the language of the project or the voice of the project. When you look at a book, you may be looking for something along the way. You may find ten other things that are completely unassociated, where you may make a different association and it would lead you down a different path where you have to go and look for a different book. But online it’s an experience in real time. It doesn’t give you a chance to get bored or to go down so many blind alleys. And often the process of making the work and the process of doing the research informs what the work will finally be. The more organic that process is for me, the more creative I can be. It gives me time to think.

CKE: Would you distinguish between a good and a bad image?

MB: I think the distinction between a good and a bad image is more about the subtext of the image. For me, it’s not about good or bad, it’s about whether I connect to or respect the concept behind what the artist or the photographer is trying to say, rather than just the image. One can have a beautiful image which evokes no emotion and means absolutely nothing. And that’s much less interesting than looking at a challenging image where I may not connect to the image, but I definitely connect to what it’s trying to say.

Anthology, Marco Brambilla

CKE: We’ve also observed an upsurge of user generated content. Today, everyone can be both consumer and producer. How do you feel about this as a professional imagemaker?

MB: Professional is a tricky word because, as you say, there’s so much migration in terms of how a DJ can be considered an artist, and an actor is an artist. Ultimately, you’re judged by the legacy you leave behind and your body of work even while you’re still working. You’re judged by the body of work.

A “creator”, or a person who is making work primarily to communicate over social media channels. That’s not necessarily someone who could be considered to be an artist. You really need to have something to say. Whether you’re doing it as an amateur, putting out videos on YouTube for instance, or exhibiting your work in a museum or gallery, I think ultimately it’s about what it is you’re trying to say and how your output informs that and how it builds a narrative and a dialogue between your audience and yourself.

There is currently a debate about AI. People can use AI tools to generate visual content much the same way as generating text, and so the question is: where is the authorship in that? Where’s self-expression? You can create a photoshoot without having to work with humans or physically go to a place. But then, isn’t this what we actually enjoy doing? That’s why most of us got into doing this. If you’re a photographer, you actually enjoy taking pictures. If you’re an artist, you enjoy making art. If you’re an illustrator, you enjoy making illustrations. I don’t quite understand where AI fits in because it’s removing the part of the work that you enjoy, what you hopefully would want to do on your own.

CKE: How would you define authorship when an artist is working with AI?

MB: Authorship comes in when an artist is using it to produce work that’s different from its application as a research tool. It can be a great tool to gather massive amounts of research done in an efficient and comprehensive way. This makes it even easier for people with limited budgets to be able to do things quickly and efficiently. But to actually produce work? No. I’ve completely moved away from that. I made one experimental piece that dealt with the concept of AI. I used AI to make it, but it was a hybrid. It was never entirely AI. And now I’ve completely abandoned the idea of making work using AI. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with it, I just personally don’t find it interesting to use a tool that removes my authorship from what I do.

CKE: Influencers, product placements, movie trailers, and political propaganda all compete within the same visual economy and on the same platforms, even borrowing visual strategies from each other. How do you see the role of the artist in this inundated system?

MB: There are artists who make beautiful, self-contained work that stands outside the system. I’m the type of artist who likes to comment on what’s going on in my work. There have been many things that need to be negotiated with the way we communicate. I’m working on a project right now which deals with this concept. Can there be a utopia in a world that is so mitigated by disposable imagery and disposable ideas? I think what you’re saying is there’s so much cross-referencing between politics, news, and economy, we’re kind of living in a post-political, post-ideological, post-religious, post-belief society.

I remember it was very disturbing to see in the news how a presidential election did really well because their TikTok campaign was incredibly successful. They are using these techniques which are, again, soundbites, not deep information. As such, you don’t really know what that candidate stands for. You don’t really know what his political views are, but you know that you like his output because it’s done well. But that’s propaganda. It’s a tool to desensitize people and control them to do something that they may not otherwise do if they were actually studying these things. We’re living in the age of propaganda. It’s personal propaganda to be an influencer on Instagram, it’s political propaganda to have slogans that have no basis in reality. Even someone like Donald Trump only exists because the consumer is there to believe that he’s a reality TV show personality who can basically say anything whether it’s true or not. If that same person was communicating his ideas in that way 20 years ago, he would have no connection to his audience. There would be no way that that person would be elected.

Dedicated Feature

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat