A Nine-Part Study of Hip Hop’s Mixtape Cover Art

|Eva Kelley

A Nine-Part Study of Hip Hop’s Mixtape Cover Art

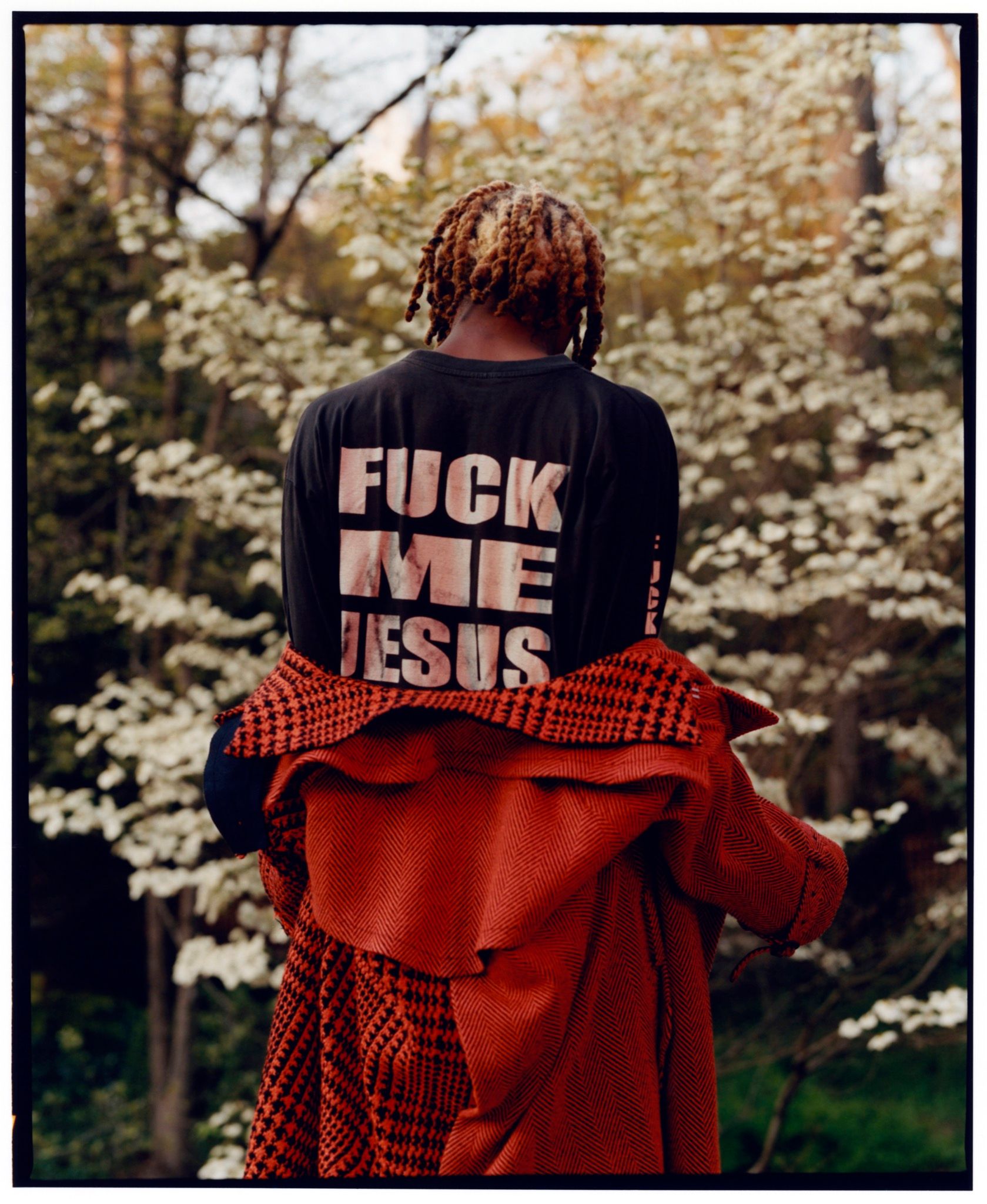

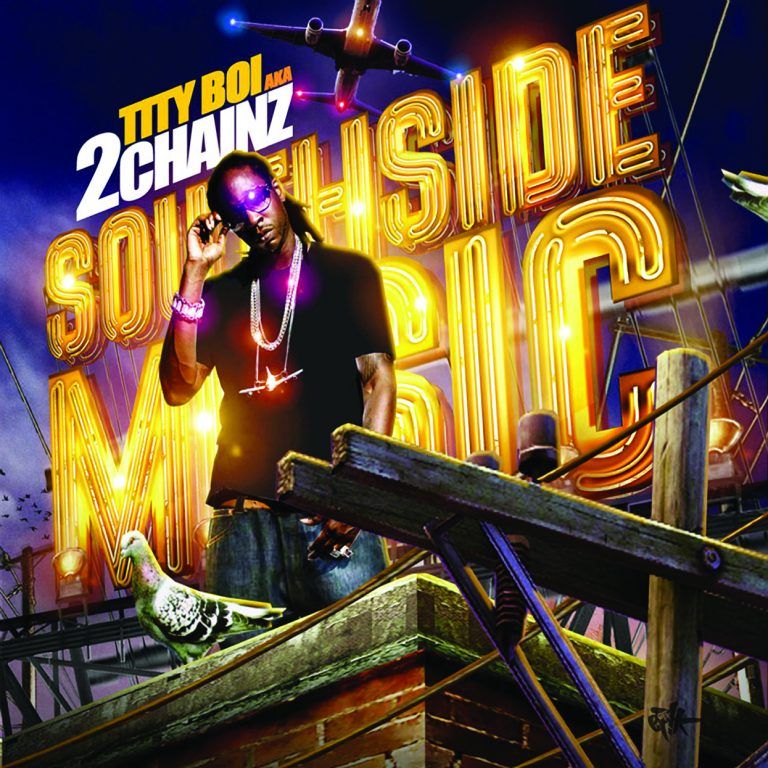

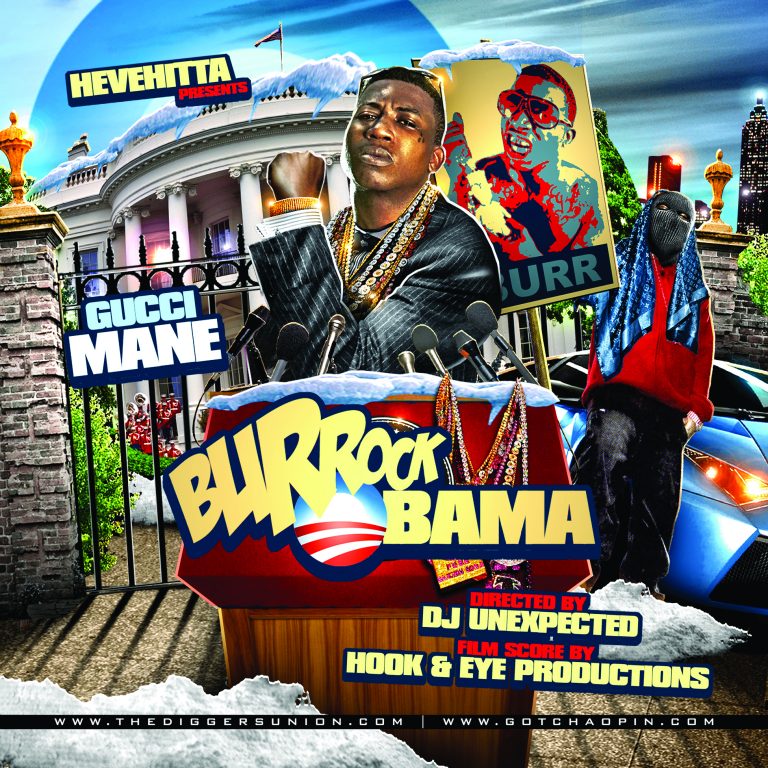

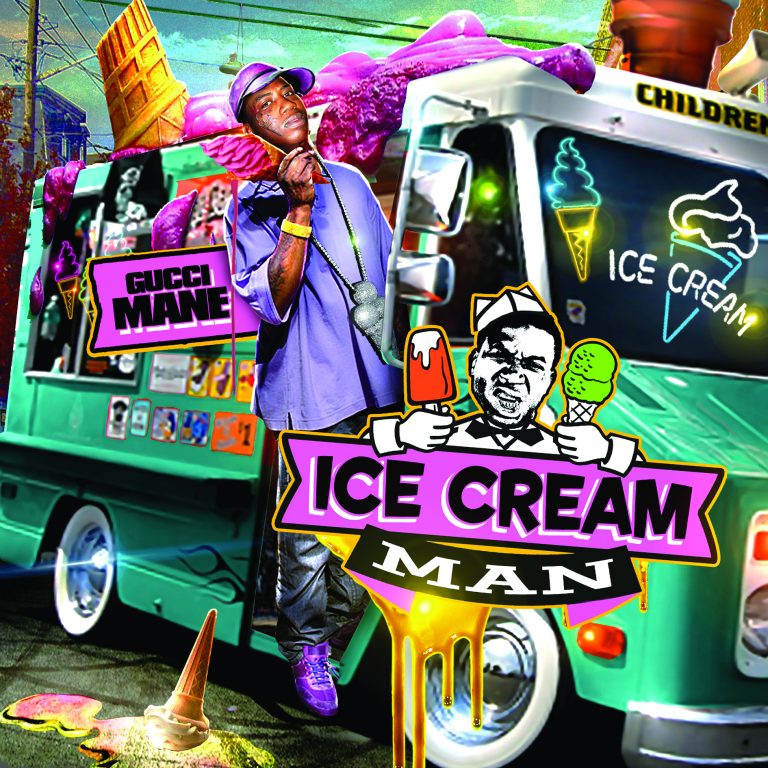

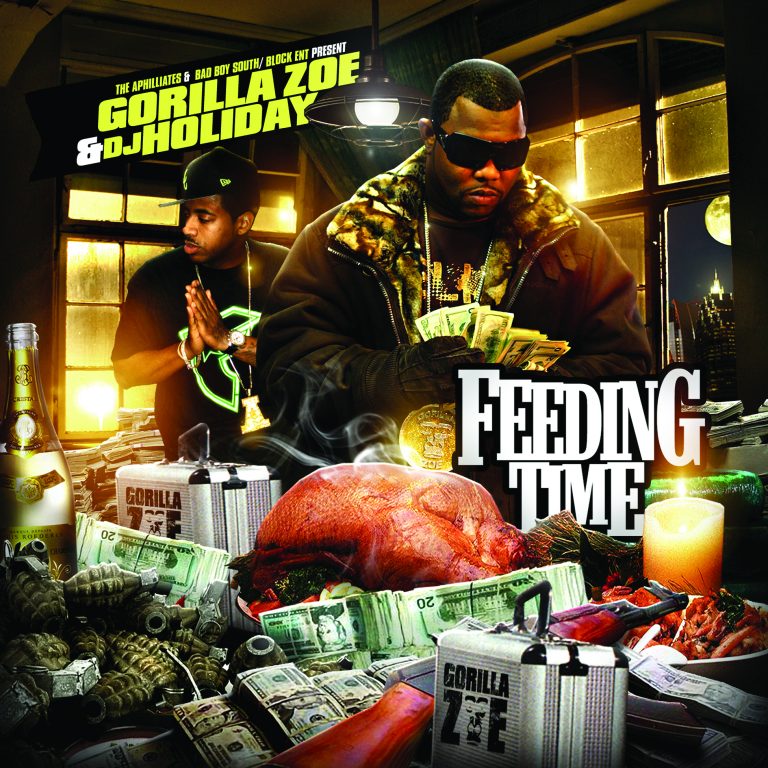

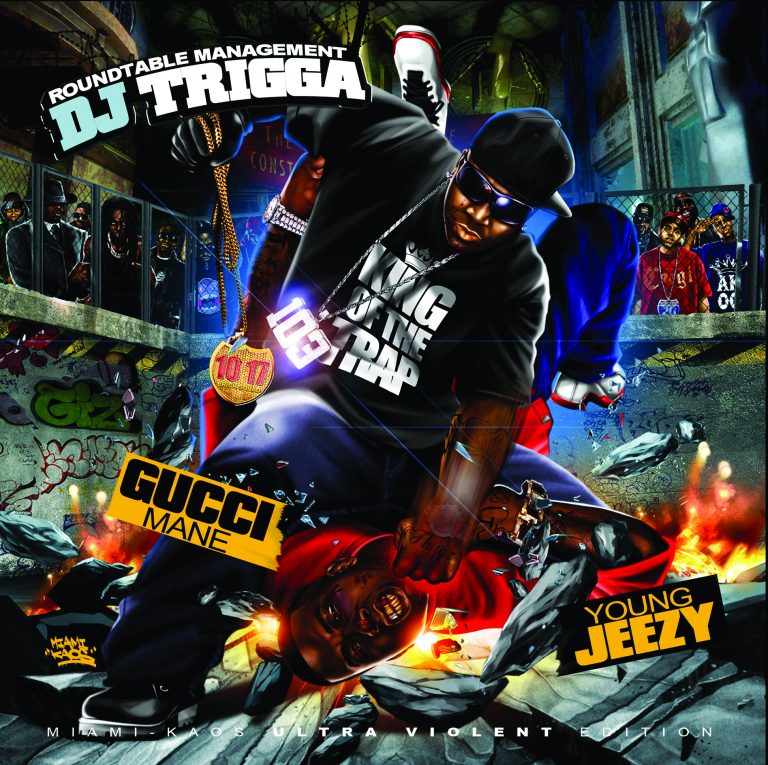

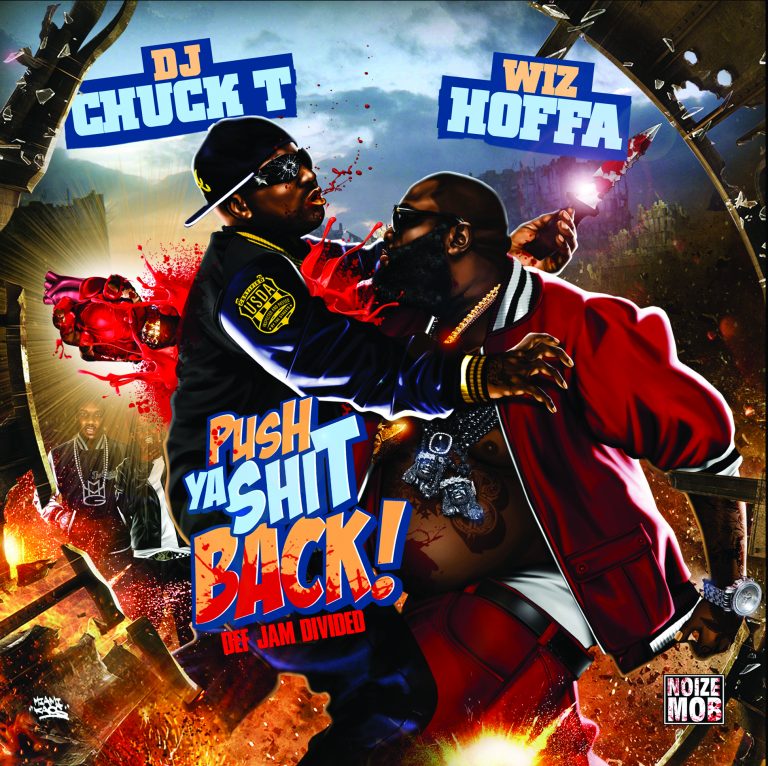

The mixtape is so much more than just an empty shell without its audible content. Created rapidly, yet in overwhelming detail, it is an often overlooked aspect of graphic design history, complete with its own masters and referential patterns. Yet it is also an uninhibited field, one subject to the freedom of fantasy. The photoshop wizards presented in the book Damn Son Where Did You Find This? exploit the zero restriction zone granted to them – a loophole in a world bursting with Parental Advisories, weaving kaleidoscopic scenes of cash, diamonds, and copyright infringement. Art directors Tobias Hansson and Michael Thorsby document the largely unknown graphic designers behind a golden era of mixtape art in the early 2000s. It is a tribute to those who generated an endless stream of cover dreams, combining original cover artworks with interviews with designers KidEight, Miami Kaos, Mike Rev, Tansta, and Skrilla.

032c’s Eva Kelley asked Michael Thorsby to share his favorite covers from the book and spoke to him about the personal stories behind mixtape design stars and why the FBI denied him access to their Headquarters.

Eva Kelley: What is the idea behind Damn Son Where Did You Find This?

Michael Thorsby: The book focusses on the designs of mixtape covers, which are accompanied by extensive interviews. Of course, we spoke to the designers, but also included other people in the industry like Evil Empire and Trap-A-Holics.

What was it like to get the process started?

It was really a ride. The project froze and even died a couple of times, because we didn’t have enough time. Then one day, I was sitting in a dusty apartment next to the pyramids of Giza while visiting Cairo for the election – the one that brought Morsi into power – when I received an email confirming a grant of a few thousand Euros. Thanks to this we could then travel to the US and meet all the people we had to talk to to create the book.

What was your favorite story that you got from the interviews?

Well, Trap-A-Holics managed to consume 25 plus ales at McSorley’s Old Ale House during our three hour interview in New York and subsequently swore that a certain Southern US rapper would kill for him. But there were also some real magic moments. Trap explained how he lived a stoners life, how he played too much Playstation, and smoked too much weed. Then, after losing both his parents within six months, he felt that he had to pull himself together and do something with his life. He put the work in and soon enough he was the hottest name in the mixtape world and instrumental in the re-launch of Juicy J’s career. This never made it into the book, but it’s one of the most memorable moments that we carry with us from the whole process.

Was it difficult to get in touch with everyone?

One interview that didn’t go that well was our visit to the J. Edgar Hoover FBI building in Washington DC. We had some questions for the FBI and after a series of failed attempts of contacting the bureau, I decided to just go there.

Why did you go to see them?

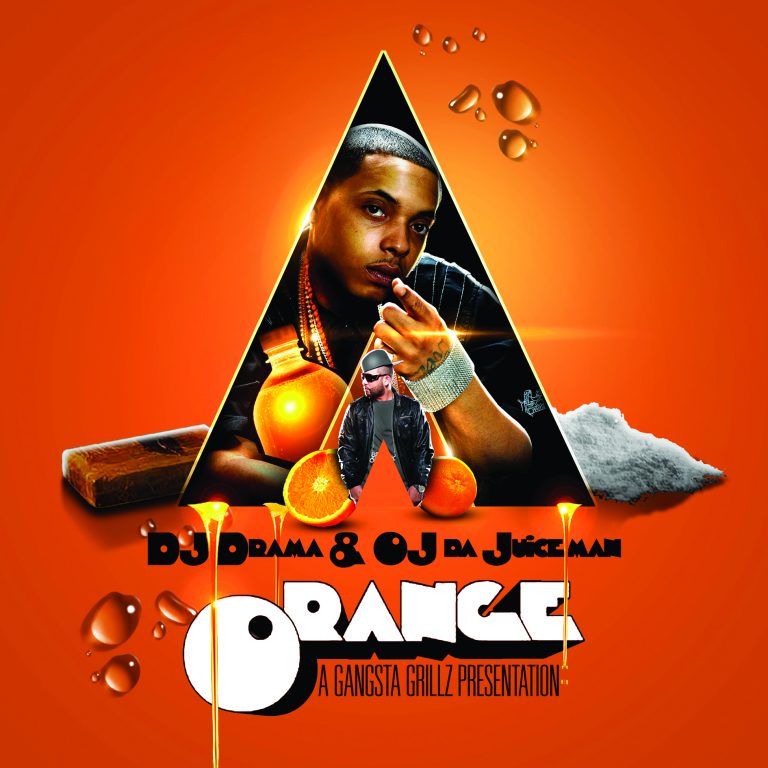

The second half of the 2000s saw a series of legal crackdowns on mixtapes. There was even one in 2007 that shook the whole industry. The FBI raided DJ Drama and Don Cannon’s office and seized 80,000 mixtapes, several cars, and froze the company’s assets. The legal grey zone operated by mixtape DJs was suddenly red hot. It took at least half a decade for it to cool down.

That’s so intense. What happened at the FBI Headquarters?

I stepped into their massive fortress on Pennsylvania Avenue and was met by 360 degrees of bulletproof glass. A woman greeted me – actually, “greeted” is definitely an overstatement. I explained the reason of my visit and meanwhile a man is stepping in from behind the woman, into my line of sight, with his right hand on his holstered gun. I was told that no visits without an appointment were allowed and when I explained my repeated attempts to get in touch with relevant personnel, I was given a little flimsy photocopied name-card with a number to a hotline. Both the visit and a couple of phone calls to the number on the card took me to a dead end.

The book still turned out great though. Why did you decide to include the interviews, instead of only gathering the visual material?

The language of the covers is so in-your-face. We wanted to find the stories behind the covers, and if possible, even set a social context. We went through the intricate stories of how the designers ended up as superstars in arguably the most extreme genre of graphic design – via booths at FedEx Kinkos to building a reputation on internet forums to seizing the moment when crossing paths with influential figures.

Did you listen to the music on the mixtapes while working on the project?

While I designed the book, I listened to Steve Reich on repeat with my daughter over my shoulder – she was barely two months old at the time – as I mainly worked nights on this project. The choice of music was made to take my mind far away from the maximalism of the mixtapes.

Why did you want to do that?

I wanted the design of the book to contrast with the content. I have never seen a book on hip hop that doesn’t try to emulate the aesthetics of the imagery it portrays – and it fails every time. Our book is based on a very simple and strict grid that aims at not taking any attention away from the work of the designers.

How did the designers that you spoke to feel about the development of the industry?

One very special moment happened late into the interview with Tansta, who, up until that moment of our conversation felt very disillusioned and was clearly ready to leave the industry altogether. After a rather negative series of answers directed at the mixtape world, he suddenly ended up declaring his love to it, realizing again how the profession had changed the trajectory of his life. He told us how in his teens, growing up in Brooklyn, he and his friends got into lots of trouble. Drugs and the dark side of a less well-off neighbourhood were dragging them down. Then he came across Photoshop Elements, a free and heavily scaled down version of Adobe’s flagship software. He started experimenting with it, landed his first gig, and managed to buy a pair of sneakers from his earnings. Work took off, his life improved, he made things better for himself and his family. Meanwhile, friends around him got locked up, some even passed away. It’s the classic hip hop story, but instead of the microphone being the ticket out of a destructive lifestyle, this story centres around Photoshop.

Yeah, that’s so true. It’s like the nerdy side of hip hop.

It’s a wonderful twist to a story that has been told an endless amount of times.

Credits

- Interview: Eva Kelley