KESHA LEE’s Trap Resume

|Philip Maughan

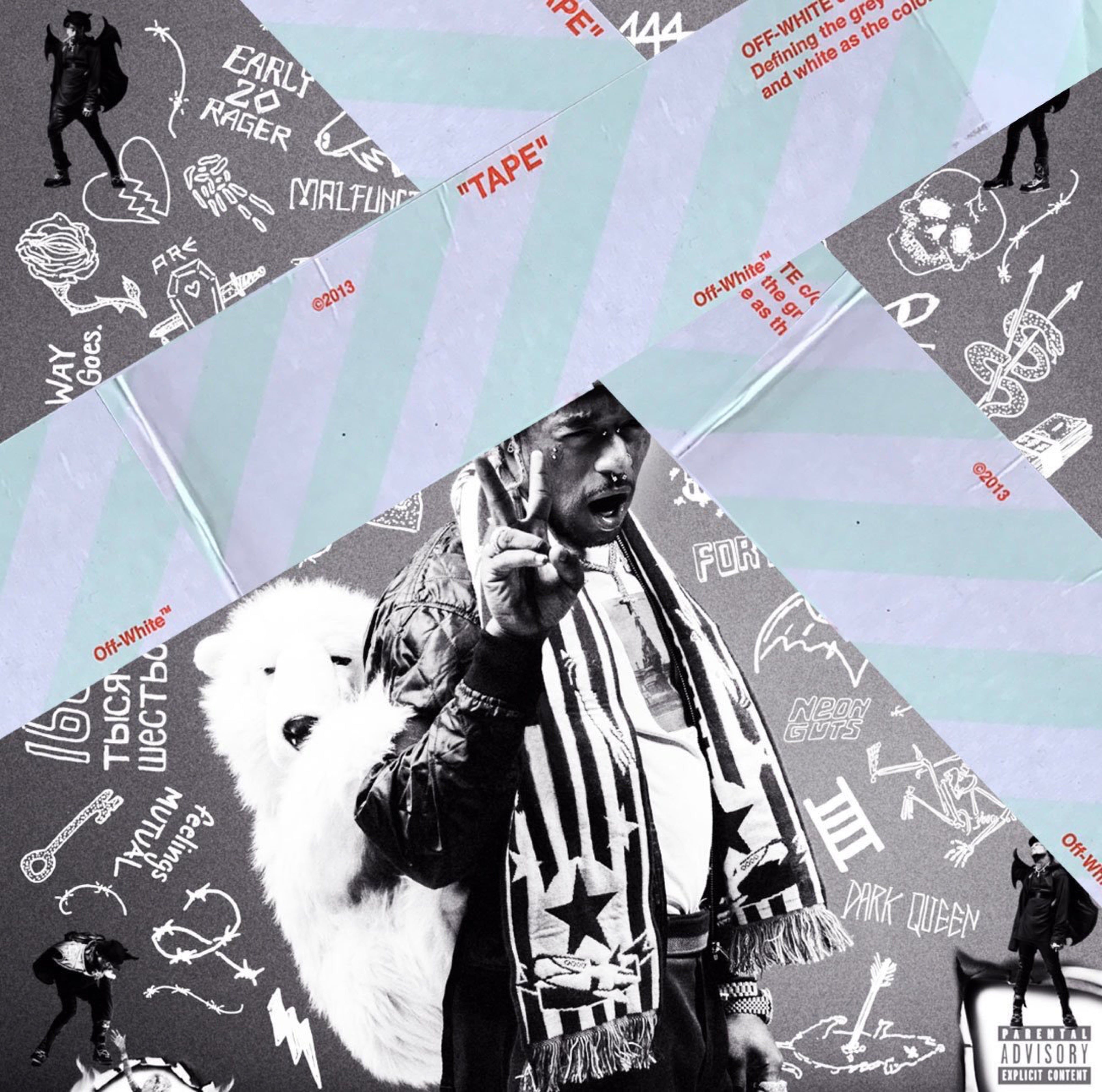

“PRO TOOLS IS MY VIDEO GAMES” reads the Instagram bio of 30-year-old Kesha Lee, an Alabama native who as you read this is probably backstage at an arena somewhere, shuffling through a departure lounge, or crouched in a broom closet setting up a condenser microphone.

Crowned a “Secret Genius” by Spotify in November 2018, Lee is not a singer, rapper, or podcaster. She is an engineer: she records, drops, and mixes vocals, and has moved Midas-like through the early phase of her career. Just a sample of the Grammy-nominated tracks she’s transfigured into gold and platinum certification awards: “This is America” by Childish Gambino, “Bad and Boujee” by Migos, “Magnolia” by Playboi Carti,” and “XO Tour Llif3” by Lil Uzi Vert, for whom she now primarily works. There’s no secret formula for predicting a hit, but searching out Lee’s name on the credit list might be a good start.

Lee was introduced to engineering when she took an internship at the radio station 98.7 KISS FM in Birmingham, Alabama, where local radio DJ Buckwild observed her aptitude for editing commercials on the studio’s production software. Yet it was after moving to study at the Atlanta Institute of Music in 2012 that her first breakthrough came, as it often does, under the patronage of Gucci Mane. While still a student, Lee worked amid the chaos at Gucci’s Brick Factory studios, recording a stable of superstars-to-be including Young Thug, Migos, and Young Dolph until the rap patriarch’s incarceration in 2013.

The difficult years that followed are referenced regularly on Lee’s social media, a feed that mixes honest wonder at later successes (“First time on a private jet!”) with humbling reminders that it was never easy. Lee is an inspiration to her followers not only because she is a woman excelling in the twin fraternities of both rap and audio engineering, but because she is the perfect example of an introvert quietly mastering her craft and thriving in a world of egos and noise. On an afternoon at the end of summer, 032c’s Philip Maughan spoke to Lee on the banks of the Spree.

Philip Maughan: Your first encounter with engineering came during an internship at 98.7 KISS FM in Birmingham. What happened there?

So, [Buckwild] had me practicing cutting commercials, and saw that I picked up on it really quickly. He told me to talk to [radio personality] Isis [Jones] because she went to school for broadcasting, and her school also offered engineering. I looked it up online and was really intrigued. I realized I was doing a type of engineering at home playing on my mom’s computer – using Garageband – but I had no idea you could pitch the voice, and add reverb and delay, and I wanted to know what the parameters were for plug-ins and stuff. I researched!

Then you took it to school in Atlanta. How did you start working more professionally?

I guess it was my first job [at the Brick Factory] that helped me move into engineering professionally. We were always working. It was always hands on, learning something new every day, learning how to record different people. I feel like I grew a lot in that short amount of time. It got to the point where I didn’t even leave the studio. I just packed a bag. And, you know, the person I was working for was Gucci Mane – and he was on house arrest at the studio, so he lived there. He always wanted to work so I ended up living there too. It was crazy.

So Gucci has a tag on his leg and he’s got to stay in the building. That must’ve been quite a strange atmosphere in which to learn.

Yeah, it was hectic. There was always a lot of people and everyone either wanted to start rapping or they were already rapping. When someone was done in the booth, someone else wanted to go in and record a song. It was non-stop. Sometimes Gucci’s engineer Sean [Paine] and I would tag team. When he was asleep, I would be recording; if I got a chance to sleep, he would record. The studio down the hall was supposed to be an office but nobody was using it so I slept in there. I was new to engineering – and new to, really, everything – so sometimes I was too scared to sleep!

And then what would you be doing? Could you break down the process of engineering in this context?

So, simply, if you’re a rapper or a singer, you go in the booth, and you sing. I record the vocals to the music. I don’t make beats or anything. Usually the artist will pick the music they want to sing or rap to, and I’ll load that into Protools. I edit and clean it up as we go.

So you’re dealing with the artist in a pretty intimate way, responding to them. What’s the weirdest ritual you’ve witnessed in the studio?

Sometimes people bring animals. I’ve heard there was a tiger in the studio – but I wasn’t there that day. I’ve seen a monkey. A lizard. What else is there? I’ve seen a life-size Harley [Quinn], from that movie, with the red and blue. With the pink toes.

Suicide Squad.

Yeah. What’s up with that?

Wait, someone dressed like her?

Just a life-size fake . . .

That’s actually a lot weirder.

I guess that wasn’t really a ritual, but it’s an example of the things people do to entertain themselves while they’re there.

I’m familiar with the idea that some rappers want a party atmosphere, but some people must be the opposite, right? They want more of a studious environment – to be clear-minded and to think.

Oh, I wish. It’s pretty chaotic. There’s lots of people. Lots of junk food. You know, people like to smoke lots of weed.

Of course.

It really is about creating an environment so that the artist can be comfortable. You would think in the studio they want to be able to concentrate and have it be a little more quiet. But when you’re in there all day, you do want your friends there to keep you company.

So your routine came to an end with Gucci’s return to prison. It must’ve been quite strange to go from knowing what you were doing every day to becoming a freelancer.

A lot of times when you engineer it’s about your resume. I had a really good resume at the time – it was a trap resume, but it was a good one. Then when I went to visit studios they were all completely staffed, and couldn’t put another engineer in the mix. I became the person they would call last minute. Even though I wasn’t a staff engineer, I was working just as much because a lot of people were requesting me – and they all wanted to work. Now when I freelance, I get an email from the artist directly. I ended up putting my email in my Instagram bio, so where before it was just within Atlanta now I’m being brought out to wherever the artist is.

Like when Childish Gambino flew you out to Hawaii?

It is crazy.

While we’re talking about your Instagram, it really struck me how honest you are about the downsides of touring. You’re being very real about things like health, relationships, losing your sense of self. Was this a conscious decision?

No. When I first started my Instagram, I wasn’t doing anything at the time – though I knew I wanted to engineer – so it was just a bunch of selfies. Then when I was doing regular sessions I enjoyed taking pictures of the different rooms I was in. But after I became more of an in-house engineer for Means Street [Studios], I wasn’t really moving around. I didn’t have much to take pictures of, so I just started sharing what was going on with me.

Some people will say, “You’re sharing too much,” or, “You’re telling too much of your business,” but then it got to the point where people were DMing me, telling me that I inspire them, and that the captions had helped them, and that they’d learned things. That was why I kept sharing information. People could see my journey, see my growth, and see what I was going through. I didn’t expect it to mean anything. I was just doing it because I wanted to have a purpose for my Instagram.

You wrote something there recently about dressing up for the studio.

I dress down a lot, just to be comfortable, you know. Pretty much PJs sometimes. But then it gets to a point where I want to dress up because I’m always in the studio and I have these clothes that I don’t get to wear. Sometimes I wear heels to the studio – though only with artists I work around a lot. I wouldn’t feel comfortable working with someone for the first time when I’m all dressed up. But yeah, sometimes I’ll come to the studio in heels, super dressed up – not for anybody else, for me.

What’s it like engineering on tour, for example with Lil Uzi Vert – are you recording stuff there or are you doing sound engineering?

Basically I’m a mobile studio. He can’t go to his studio to record because the schedule is so tight, so I have the mobile studio, and we’ll do a studio session.

Who else have you been working with?

Actually, I’ve just been giving Uzi all my time, because he’s been working on an album. I don’t know when it’s coming out, but it’s been a long recording process. It makes me nervous on my end because I know we get all this time to record, and once he picks his songs, he’s not going to want to wait on the mixing process, or the other creative processes. I’m trying to change my workflow so when he’s ready, everything’s ready, and he doesn’t have to wait too long on it.

Could you say something about how you work with a producer?

With Uzi, he’s always getting beats sent to him. Every now and then they’ll have a producer come and give us beats, or sometimes they’ll make a beat in front of him, and he’ll give input too – or like, “I like that sound, keep that.” Then it’s really simple. I try to format the song as we go, but sometimes I think that there’s something that he’s looking for as far as beats and I don’t know if he’s found it yet. He likes to stay productive. So he’ll pick a song and just pick a part of the beat he likes, and he’ll just duplicate it out and just use that for the whole beat. It’s a little different and more involved when I’m working with singers like Childish Gambino. You know, he has Ludwig [Göransson], and I just do what they say. I mean, I add creatively to the vocals if I can, but I try to stay out of the way because they’re such geniuses. I’m just like, “Do your thing, I’m just here to engineer.”

So it’s about helping the artist achieve their vision. At what point do you try out new things?

I don’t ask. I just do it. And a lot of times people welcome that. With some situations, I’m nervous because maybe it’s a really big artist, and I just want to observe before I start adding stuff, and just kind of get their workflow and what they’re on. But at the same time, they brought me out there for that reason. So it’s like, don’t be shy, you know? But I do try to kind of gauge the artist and if it seems like they know what they want, I try not to add anything. I feel like it changes the direction of something – which could be a good thing, but I’d rather they get their ideas first. Because I’m here for you and what you’re trying to execute, but they really do like bouncing off of each other. So sometimes if I do something, that gives them their next idea or something like that.

How much have you done with Childish Gambino?

I worked with him in Atlanta, and I guess those sessions were good because he invited me out to Hawaii. This was on and off because he was filming at the time.

It must be strange to watch something like “This Is America” blow up.

It was, but with Uzi, that was the craziest. It went from my boss asking me, “What do you think of him?” and me saying, “I love him.” You go from that, working maybe a year, and then suddenly everybody else loves him too. You go to a show and people already know the words. It’s crazy to think that you were a part of that. It’s the coolest feeling, and I would do it a thousand times. I really do enjoy what I do, and that’s why I just do it all day every day. And if I’m not doing it, I just feel like, “What am I doing right now? Fuck my life!”

Credits

- Interview: Philip Maughan

- Photography: Fabian Brennecke

- Thanks to: Red Bull Music Academy