The Saddest Drip

|Shane Anderson

What’s in a name? Some say, your destiny. There are more dentists named Dennis than chance would dictate, and I’d like to think my perpetual feelings of shame are related to my birth name. The importance of names, of controlling your destiny, are not lost on artists who wanted to eschew patriarchy, for example, such as Prince (insert symbol), George Sand, and Pablo Neruda. Nor is it lost on the Turkish-German trap artist Ufo361, whose name perfectly corresponds to the reality of his music.

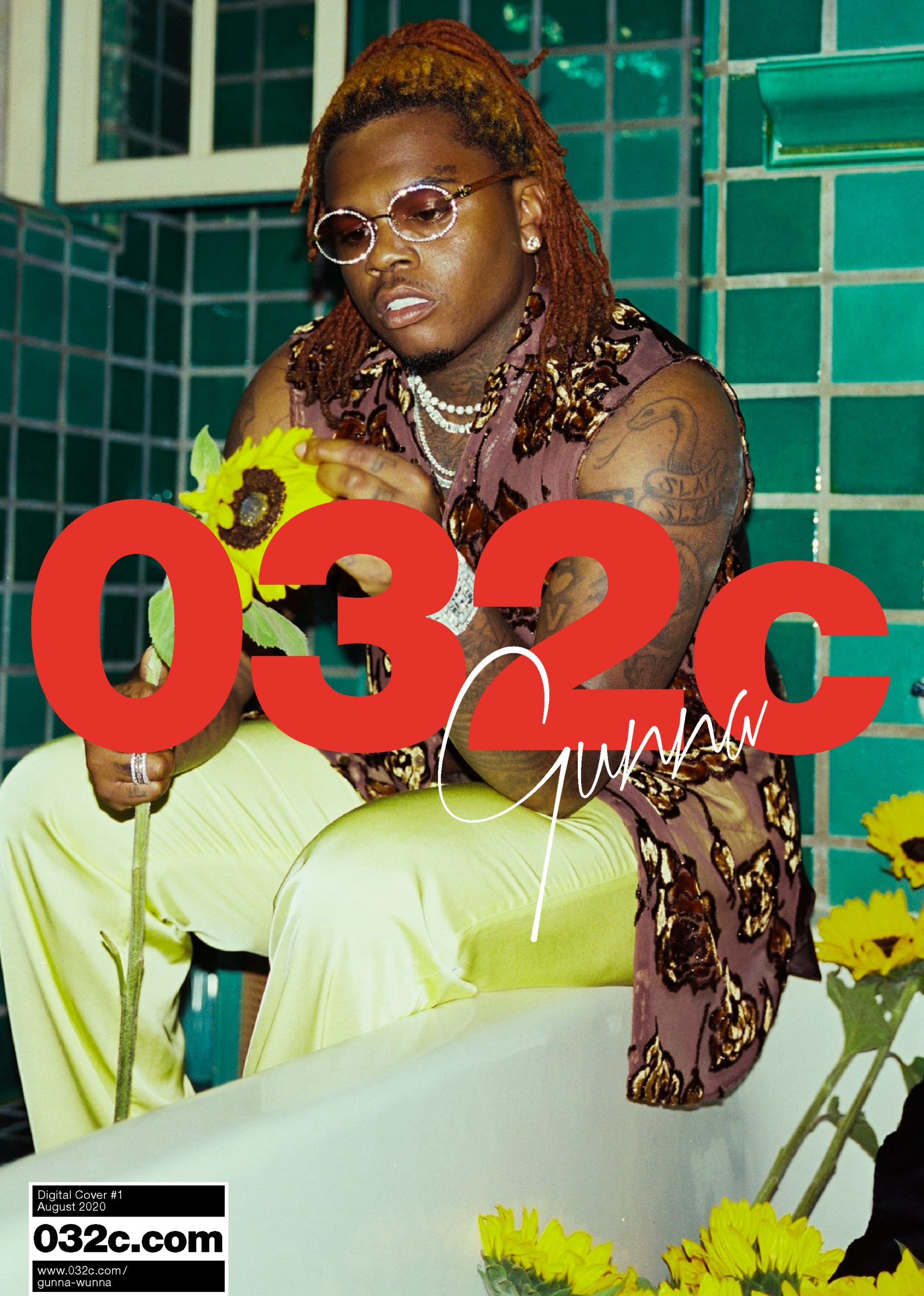

Ufo361 was born as Ufuk Bayraktar in West Berlin, and the name is both a play on his first name and a shoutout to Kreuzberg’s two postal codes before the fall of the Berlin Wall: 36 and 61. But his moniker suggests more than that. Ufo361’s sound and early adoption of Atlanta’s trap music suggests coming from afar but he still (mostly) raps in the language of his primary audience: German. Nevertheless, Ufo361 has shot into the outer orbits of fame, collaborating with trap legends including Quavo, Gunna, and Future.

It is this blend of the foreign and the familiar that have made him an absolute star in Germany. His most recent album, Stay High, was number one in the German charts, and you can now hear trap being bumped in cars, bike repair shops, and burrito joints. And everywhere you go, it’s Ufo361’s distinctive voice that you hear most often.

I spoke to Mr. Bayraktar over Zoom while he was in Italy preparing his next shoot.

Shane Anderson: What characterizes the Ufo361 sound?

Ufo361: There’s the influence of the whole Atlanta trap scene of course, but there’s also a certain melancholy, which comes from my Turkish heritage and the Turkish music my father listened to at home. Added to that is the way I use my voice. The effects I use, the melodies. My trap tracks are rougher and dirtier than what was going on in Germany before I started.

Could you say you were the first “German” rapper doing trap?

I can’t say for certain. There were a lot of underground rappers that were also moving in this direction, but it was often done as a parody. So yeah, I guess I’d say that no one was doing it quite like me before.

Your early records were also playful, much like these parodies.

True, my early mixtapes “Ihr seid nicht allein” and “Bald ist dein Geld meins” were more playful and had their own take on “feel-good music,” but this quickly changed when I started going in the trap direction.

In lyrics from the album 808, you say: “Das Einzige, was sich verändert hat, Bro, ist mein Kontostand” (“The only thing that’s changed, bro, is my bank balance”). Is that true? Has there been no development?

There’s definitely been a development in the music. What I meant with that line is that my mindset has stayed the same and I’ve remained true to myself and who I am. I haven’t turned into someone else just because of my success. Just because I have more money doesn’t mean I’m a different person.

“Engelsstaub doesn’t sound as nice as angel dust.”

You don’t think money changes people?

Maybe your lifestyle changes. Maybe certain interests change because you never had access to them before. Money can also push your art practice and you can do bigger things than you could have before. Yeah, money allows you to do all sorts of things. You can make donations, buy a new car, whatever.

You also mix in different milieus.

For sure, but none of that changed my mindset.

How would you describe your mindset?

In a nutshell? Determined. Purposeful. Focused. I always try to achieve the goals I set myself, goals that I maybe even set myself as a young boy. I had a number of role models growing up and I learned to not get caught up with other things. I learned to keep moving forward and finish what you want to achieve. This is something I want to help others with, through my example.

You want to serve as a role model.

For sure. Don’t get me wrong, flexing, cool cars, expensive jewelry and beautiful women are the standards in hip hop culture and that’s fine, but I think it’s important to also go beyond them and that’s what I’m trying to do.

Did you always want to be a rapper?

By the time I was 14 or 15 yes, but before that, hip hop was just always around. My brother listened to hip hop when I was really young, and it was always there in the older gangs and crews who spray painted all the walls in our hood. I remember being 8 and being totally fascinated by how creative you could be with colors in the city. This inspired me to then also become involved in the graffiti scene, and THC in particular. Graffiti is a bit underrated in the hip hop scene today, but hip hop and graffiti were always interconnected. You could say then that one thing led to another. But I stopped spraying around 2010, 2011.

Around the same time, you started getting more serious about music. You would then go on to release three albums entitled Ich bin ein Berliner. This suggests that you’re very anchored in the Kreuzberg scene and yet your Turkish heritage has never been directly addressed in your music. Neither in samples nor in rapping in the Turkish language.

No, it hasn’t. But yeah, my producers and I have used rhythms and samples from all over the world and we were in conversation with a legendary Turkish singer, but it didn’t feel like it fit with the trap sound. Still, I really don’t want to lose my connection to my roots, and I’d really like to do something where my mom, my aunt or my uncle say, “Wow, you performed with Ajda Pekkan.” I mean, they also think it’s cool that I performed with Future and the Migos but it’s a bit different.

One thing that occurs to me is that the new album, Stay High, mixes languages much more than the previous ones. In a way, it’s rapping in a mixture of English and German.

I wouldn’t say it’s more extreme in this album than in the albums. It took off when I made the album “Ich bin ein Berliner” and has slowly grown because I started working with artists in America more. I spent seven weeks in Los Angeles, chilling with professional producers and rap stars. I saw how they ate and spoke and drank and recorded and ticked. It was something I picked up. Especially after working with Future or Quavo. There, I really experienced what trap culture is. This then intensified the use of English in the tracks. As a German artist, it’s more interesting to be able to be understood by both Germans and Americans, especially if you’re collaborating with them. You want them to be able to understand what you’re saying without a translation, even if there are a few German words in between. And sometimes English just sounds nicer than High German. Engelsstaub doesn’t sound as nice as angel dust.

What language are you at home in?

Turkish. But I’m trilingual. I speak Turkish at home, I live in Germany and work in German but musically my language is American.

Have you ever considered rapping in Turkish?

I actually started in Turkish and the first rappers in Kreuzberg were Turkish. Islamic Force, Cartel, et cetera. I did a collaborative album with Ezhel, a huge Turkish rapper, and I said a few Turkish lines, here and there. But never a whole song.

What do American artists say about your work? I saw that Lil Uzi Vert posted a track on Instagram stories.

There hasn’t been a single time with these people where I sensed that they didn’t feel what I was doing. They understand that I understand the culture. That I didn’t just turn up and put a chain on my neck and talk the talk. They realize that I’m also from their world. Berlin Kreuzberg isn’t that different from Atlanta. Atlanta may be a little more hardcore but when Quavo got his money for the feature, it was real trap money. It was 4 AM—where are you going to get that much cash at 4 AM, you know? You’re not just going to go to an ATM. When he got the money, he was like, ok, this dude is trap.

And then when he heard the song “VVS” [sings], he felt it and understood immediately. I didn’t have to say a single word.

How would you describe trap culture?

It’s a lifestyle. I can’t say that I live like hardcore gangsters in Atlanta. That’s something I’ve tried to escape. I’ve seen a lot of things on the streets and don’t want to go back there. But yeah, trap has to do with difficult situations, criminality, gangs, a lot of drugs, et cetera, and then they go into the studio. They get a lot of money first and then they start rapping. In my case, I would be called into the studio from someone who wanted to buy something off me. That’s how I came to music. I didn’t just, like, dream up going to the studio to make a pop song with Paris Hilton or something. I went in because some drug addicted rappers needed my goods in the studio and would call me every day. I then said, “I’ve got bars for you” and they’d call and say, “Hey bro, can I use the rhymes you spit yesterday?” And I would say, “Yeah, but why don’t you let me do it.” Then I’d say, “Look, I’ll bring you what you need if you give me beats.” That was my trap.

The new album, Stay High, is much darker and sadder than the others. The first sentence of the album is “Auf der Spitze des Bergs ist es so einsam, ey” (“it’s so lonely at the top of the mountain, ey”).

One album that’s just as dark is 808, but yeah, I’d definitely say this is a dark album. I didn’t feel like just going for commercial success on this, my tenth album, and trying to do what people wanted. This album reflects my entire career, a number of moments in my career. The name “Stay High” [which is also Ufo361’s label name] is what motivated me to take on the mindset I was talking about earlier. I wanted to reflect on what led me to that, the darkness, you know?

“Stay High” is then more like a motivational statement than just about getting stoned.

Definitely. That’s the main idea. It came from an old New York graffiti artist from the late 1970s, Stay High 149. But I never wanted to say ‘stay high’ in the sense of ‘legalize it’ (which would be cool of course) and then sample Bob Marley and make all the lyrics about smoking weed. No, it’s about staying on top of your game, and pulling through.

Both of your darker albums, 808 and Stay High, address themes like fear, sleeplessness, nightmares, and sadness. It’s rare to hear a hip hop artist talking about these things so clearly. Can we talk about those?

That’s something I prefer to address in my music than in an interview. It’s why I make music. It’s a kind of self-therapy.

“I didn’t just, like, dream up going to the studio to make a pop song with Paris Hilton or something. I went in because some drug addicted rappers needed my goods in the studio and would call me every day.”

Are there plans to work with other trap artists in the future?

We’re getting ready to go to New York, which has been delayed because of corona. We’re in contact with Lil Uzi Vert, and I’ve showed him some songs. Let’s see when it will happen.

Who’s “we”?

In the music, it’s the same team—The Cratez, Jimmy Torrio, Sonus030, Gezin from the 808 Mafia and a few others. But I have been working with new people on the fashion stuff. Both for my own brand, No Hugs, as well as for the whole album, the videos, et cetera. A new collection just came out. This, too, had always been a dream of mine. Even as a small kid, I dressed super nice. I remember how I went to a fashion show with my father once, I don’t remember what it was, but it was totally crazy to see all these models in a Hinterhof in Kreuzberg with all this leather and… yeah, crazy.

The new work with 032c is also sweet. It’s very inspiring. They feel like family to me.

On 808 you celebrate Balenciaga but condemn Dolce & Gabbana. Is there something in particular that makes you interested in a brand and less interested in another?

Oh, that was just a thing that happened in the studio. I’ve never really thought about why a certain brand interests me, it has always been about the colors and the materials, the cuts, the look and what it works with. That’s also why I always discover new brands.

Right now, I’m really into archive clothes. Raf Simons and Helmut Lang, for instance. I feel like these things were built to last. Today everything is made to disappear tomorrow. Even a drill feels like it breaks after being used only a few times when it used to last twenty years. A pair of Helmut Lang pants that are 20 years old feel more sturdy than new ones do. And yeah, things like Balenciaga or Margiela interest me. Margiela was anti-fashion all the way back in the 1990s, doing rough things.

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson

- Photography: Timothy Schaumburg

- Clothing: 032cReadytowear “Système de la Mode” SS21

Related Content

“This shit just sounds deluxe.”

Books by ISOLARII: “Islands from which to view the world anew.”

The Aggressive Attacker: An Interview with Chess Grandmaster Judit Polgár

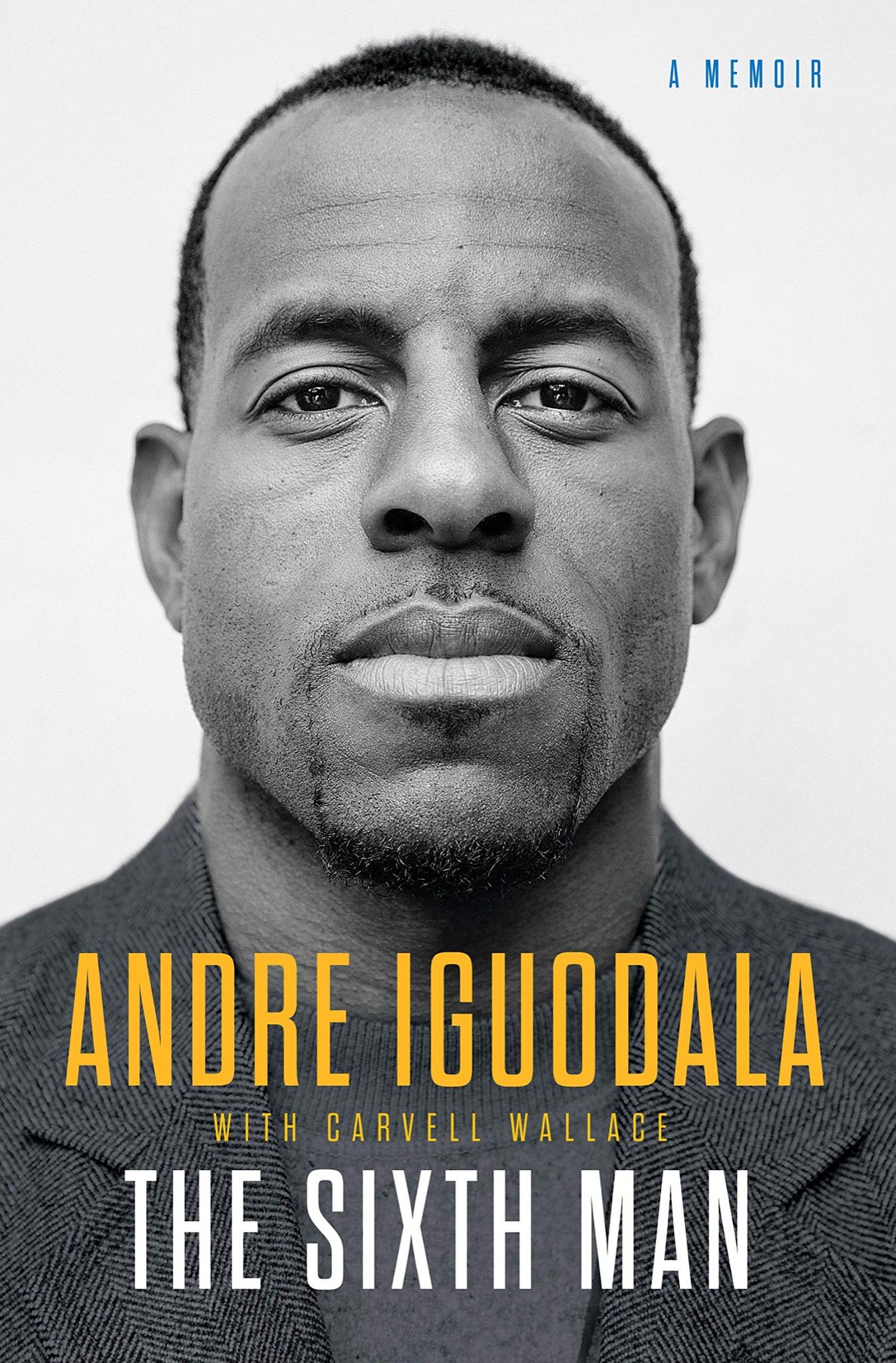

Interview: NBA star ANDRE IGUODALA talks sacrifice, freedom, and what needs to change

BREAKING: ADIDAS AND 032c LAUNCH TWO NEW SILHOUETTES