O VILLA, CIAO

|Sven Michaelsen

Giangiacomo Feltrinelli was born in 1926 to one of the wealthiest lineages in industrial Italy – powerful bankers involved in railway expansion, timber, and utilities. Growing up on the family’s vast estate in Gargnano, Lombardy, the young heir got to know the house staff – and began to take an interest in workers’ rights. Toward the end of World War II, he enrolled in the Italian Communist Party to fight the invading German Army and the dwindling forces of Benito Mussolini’s regime. By then, the family had left their home at the Villa Feltrinelli – Mussolini had moved in instead. Before the smoke of the war had cleared, his father died, and Giangiacomo inherited a fortune. He founded a publishing house, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, in Milan. The imprint took risks, releasing Boris Pasternak’s Russian classic Doctor Zhivago, unpopular with leadership in the Soviet regime, and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, banned under most obscenity laws.

Feltrinelli’s third wife, a German photographer of Jewish descent named Inge (née Schönthal), became de facto head of the publishing business as Giangiacomo committed to anti-imperialist revolution full time. He financed guerrilla movements and traveled to Cuba to meet Che Guevara. He took on a code name, “Osvaldo,” and, fearing Mossad and the CIA, went underground. It was as Osvaldo that Feltrinelli died. In 1972, while attempting to sabotage an electricity pylon outside Milan, he exploded himself instead.

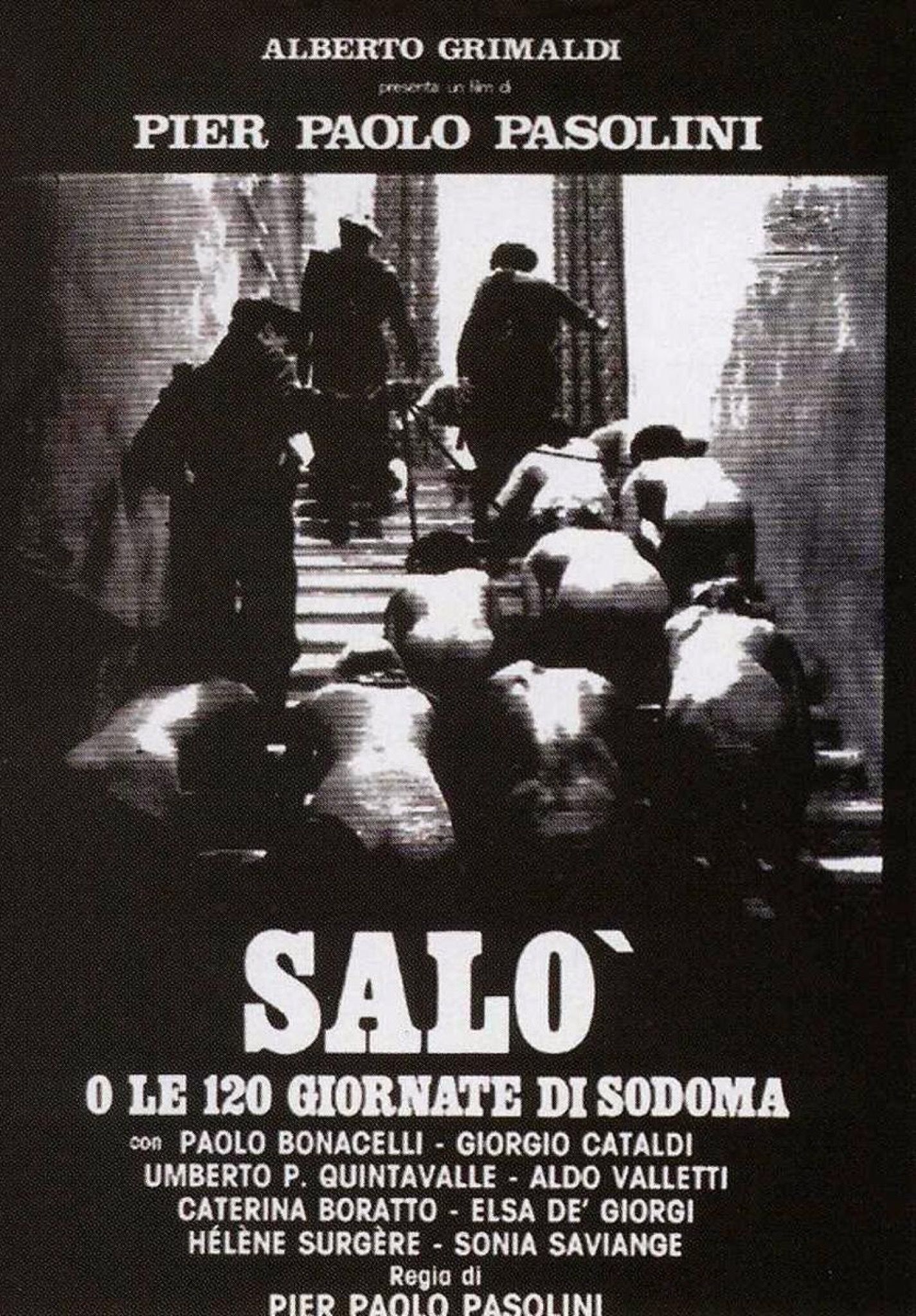

His family home, the Villa Feltrinelli, still stands today, more or less unchanged since it was built in 1892. Having once put up Mussolini – and the American soldiers sent to arrest him him there at the end of the war – and having later served as the backdrop of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), the property is now open to paying guests – and pay they do. The Grand Hotel has four times the staff than it has guest rooms. Its general manager since 2001, MARKUS ODERMATT, is the informal keeper of the Feltrinelli legacy: a century of European history at its most decadent and capricious, distilled and monumentalized in eight acres of neo-gothic luxury on Lake Garda. SVEN MICHAELSEN, who interviewed Inge Feltrinelli for 032c Issue #23, visits Odermatt at Villa Feltrinelli for lessons in politics and hospitality.

Mr. Odermatt, after completing your training at the Hotel Hermitage in Geneva, you spent 10 years managing luxury hotels in South America and the Caribbean. What brought you to Lake Garda?

Robert H. Burns, the founder of Regent Hotels. After he sold his life’s work to the Four Seasons Group at the age of 63, he had 300 million dollars at his disposal and started looking for a refuge for his retirement in Italy. In 1997 he discovered Villa Feltrinelli [at] Lake Garda, a rundown yet magnificent building on a three-hectare lakeside plot. The price was a mere 3.5 million dollars. Shortly after signing the deed of purchase, he realized that the building was much too big for him alone. He made a new plan: to turn the mansion into a boutique hotel, the likes of which the world had never seen. I was to run the house.

How much money was involved?

Burns invested 35 million dollars and spent four years remodeling Villa Feltrinelli. This process was closely monitored by officials from Italy’s historical preservation office. The gilded sterility of many other luxury hotels is something you won’t find with us. The furnishings include more than a thousand antiques; every piece of furniture is a historical original or was made especially for us. For excursions on the water, guests can make use of our 16-meter saloon boat, La Contessa.

On Garda:

Italy’s largest lake takes its name from “warda,” a Germanic word for “place of safety.” However, it has been a site of battles since Roman times, including the Battle of Solferino – a conflict so bloody it led to the founding of the Red Cross and the Geneva Convention.

Villa Feltrinelli – located in Gargnano on the western shore of Lake Garda – is a neo-gothic structure built in 1892. The original owners were local residents who had made a fabulous fortune by the end of the 19th century.

The Feltrinellis started out as timber merchants and later purchased real estate, forests in Carinthia, and railroad facilities in Vienna and Thessaloniki. They added the Feltrinelli banking company to these holdings in 1899. The Villa Feltrinelli was the family’s flagship residence, demonstrating their newfound status.

In October 1943, the German Wehrmacht seized Villa Feltrinelli and made it the residence of the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

Following countless military disasters, Mussolini was deposed in July 1943 by his own people. King Victor Emmanuel III then had him arrested and taken to Abruzzo. Two months later, he was released by German paratroopers. Villa Feltrinelli is where he announced the founding of the “Italian Social Republic,” a phantom state that ruled for 600 days with a puppet regime. Since Hitler no longer trusted the Duce, [the Führer] put him under guard, in the villa, by 30 SS officers from his Leibstandarte bodyguard division. Mussolini’s servants lived [on the grounds in the houses] that now serve as guest villas.

Did the Germans change the villa’s appearance?

Yes, the Wehrmacht had the outer walls painted field grey for camouflage and dug two bunkers, each 30 meters long. The villa’s tower was halved in order to install an anti-aircraft gun as protection from attacking planes.

“Nothing is more contagious than evil.”

– The Magistrate, Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom, 1975

How did Mussolini spend his days?

He had a tennis court built where the pool is now, and there are photos where he’s riding his bicycle around the villa’s park. He played cards with his wife, played the violin in the evening or watched Hollywood comedies [that featured] Buster Keaton or Harold Lloyd. His favorite actor was Charlie Chaplin, especially in the films Modern Times and [The] Gold Rush.

Mussolini lived there with his wife Rachele and children Anna Maria and Romano. The marriage is said to have been a farce.

Mussolini was a womanizer. He had five children with his wife, plus nine children with eight mistresses. He made accommodations for Clara Petacci, his last affair, in the Villa Fiordaliso in Gardone, just a few kilometers away. Whenever he visited her there, he went by boat.

What did Villa Feltrinelli’s domestic staff at the time say about Mussolini after the war?

It was said that the dictator suffered from anxiety. Instead of the prestigious master bedroom, he chose an adjacent room hidden by a giant magnolia tree, presumably out of fear of partisans with sniper rifles. Whenever he looked up from his canopy bed, he saw a ceiling painting that had “Ave Maria” written in large letters [at] the center. Those who book the Suite Magnolia with us sleep in Mussolini’s former bedroom and look up at the same ceiling painting. His desk is in the corridor, and in the stairwell are two giant mirrors he brought with him from Rome. Like 90 percent of the villa, his desk and the mirrors are listed as historic monuments.

Mussolini didn’t like his new home. He denounced Lake Garda as being a “cross between a river and the sea,” and saw Villa Feltrinelli as a “gloomy, sinister” hole.

His relationship to Lake Garda was ambivalent. He had a connection to the region because Gabriele D’Annunzio lived here, [Mussolini’s] greatest idol, and a thinker behind the fascist movement. Even before D’Annunzio’s death, in 1938, Mussolini declared the poet’s villa, Il Vittoriale, a national memorial. Yet the Duce suspected that the war was lost. His health was quickly deteriorating, and he was suffering from depression.

On April 25, 1945, the 61-year-old Mussolini fled advancing US troops and headed toward Switzerland with his mistress, the 33-year-old Clara Petacci. Two days later, disguised as a German corporal, the ex-dictator was recognized by communist partisans on Lake Como; [he was] executed the next day, with seven shots from a submachine gun. Petacci was raped, then executed as well. Their bodies were sent to Milan, where they were hung upside down from the roof of a gas station and desecrated by a vengeful crowd.

At the height of his power, Mussolini once said that “everyone dies a death which befits their character.” Had he remained in Villa Feltrinelli, he would have met a different end. The Americans had issued the order to take him prisoner and bring him before a court. The plan was to hold a trial like that [in] Nuremberg, where Nazi leaders were held accountable for their crimes. But Mussolini feared that he would be given a show trial in front of thousands of spectators at Madison Square Garden in New York. That’s why he decided to flee. A similar motive lay behind Hitler’s suicide in the Reich Chancellery’s bunker. He thought the victorious Russians would drag him through Moscow in a rat cage as a trophy.

In the 1950s, the villa became the summer residence of Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, first heir to the Feltrinelli empire, who lived in Milan. In the 1970s he was famously internationally sought by the authorities for allegedly financing terrorist groups.

Feltrinelli had two great passions: books and politics. He turned the villa into a think tank for his publishing house, which he founded in 1955. He also pampered writers and intellectuals here – people such as Saul Bellow, Tennessee Williams, Umberto Eco, Max Frisch, and Ingeborg Bachmann. In his early 30s, he was considered a “miracle man” on the international literary scene after successfully publishing Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard and obtaining the global rights to Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. Two world best sellers in two years – no one had achieved that before him. He then went on to publish a diverse group of authors, including Che Guevara, Nadine Gordimer, Gabriel García Márquez, Günter Grass, Michel Foucault, Rudi Dutschke, Doris Lessing, and H Chí Minh.

In 1958, Feltrinelli met the German photojournalist Inge Schönthal at a Rowohlt party in Reinbeck. Schönthal – who had photographed stars such as Greta Garbo, Gary Cooper, and Ernest Hemingway – later said of the evening: “Giangiacomo was 32, dressed poorly, smoked one cigarette after another and chewed on his nails. He was introverted, shy, glum, very complicated, and full of self-doubt – a real Italian intellectual. With my frivolous impertinence, I was a perfect complement to him – and thus just the right wife for him too. Our common denominator was that we lived life in the fifth or sixth gear. It would only take us five minutes to pack our bags and we’d be off to visit Henry Miller or Karen Blixen.”

Feltrinelli’s life bore features of a novel. At 17, he was a partisan and fought against the German Wehrmacht. Then he joined the Communist Party. At 21, he inherited a fortune worth billions and organized camp-outs at Villa Feltrinelli for young communists, much to the horror of the parish priest. At 41, he was photographed for L’Uomo Vogue [while he was] wearing a beaver fur coat and a Russian cap – which earned him the derisive nickname of the “perfumed revolutionary” amongst conservatives. At 43, he went underground with a forged passport and financed radical left-wing guerilla organizations all over the world – at least, that’s what the Italian security agencies believed. They searched for him in vain.

On March 14, 1972, Feltrinelli’s mutilated corpse was discovered in a field outside of Milan. According to the police report, the 45-year-old accidentally blew himself up trying to destroy a high-voltage electricity pylon with 15 sticks of dynamite. His widow never believed this version of the story, saying it was more likely that he was the victim of a murder that was covered up: “As a mountaineer, climbing up that power pole would have been like drinking a cup of coffee for him.”

There are dozens of theories about who might have murdered Feltrinelli. Some say it was Israel’s Mossad, since Feltrinelli is said to have given money to Yasser Arafat, chair of the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization]. Others claim that Italian intelligence agencies wanted to get rid of a terrorist financier. The truth will probably never come to light.

“We were the leopards, the lions, those who take our place will be jackals and sheep, and the whole lot of us – leopards, lions, jackals and sheep – will continue to think ourselves the salt of the earth.”

– Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, The Leopard, 1958

After Feltrinelli’s death, the publishing house hit a financial crisis that threatened its existence. The Villa was hardly used, and was finally sold at the end of the 1970s.

It’s a sad chapter of the story. The buyer was an Italian real estate development tycoon who let the building go to rot.

The Feltrinelli publishing house, with its 122 bookstores, is now run by Feltrinelli’s only child, the 58-year-old Carlo. Do you know him?

Yes, he visited us once at Villa Feltrinelli with his family. He said at the end of his stay that he was pleased that the soul of the house was not damaged in its transformation into a Grand Hotel.

Carlo Feltrinelli also bought the villa next to you – and had tall cypress trees planted to block the view of his father’s house. People in the village say they’re not sure if he spends time at the house at all. Do you know?

No. Apparently, he’s a mystery man, just like his father.

Is it true that Romano Mussolini, the youngest son of the Duce, played the piano here?

In 2003, a man rang the buzzer at the entrance gate to the villa’s park, claiming to be Mussolini’s son. He said that he wanted to sit behind the piano for a few moments again, having played that piano every day between 1943 and 1945, often accompanied by his father on violin. When the receptionist didn’t believe him, he asked whether he could speak to the director. As I was suspicious, I didn’t invite the man in, and instead ran to the gate to first get a look at him. Standing in front of me was a man in his mid-70s – he was not in very good shape – and something told me that this story could be true. And in fact, it really was Romano Mussolini, a celebrated jazz musician who had played with Chet Baker, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, and Caterina Valente, and who had married Sophia Loren’s sister. His daughter from this marriage, Alessandra, went on to lead a neo-fascist party and become a member of the European Parliament.

So, did he actually play the piano then?

Yes, for about 30 minutes. Then he asked to be allowed to walk around the house without accompaniment, so that the memories could surface. When he came back from his tour, he asked for a glass of water, thanked us, then left. He never came back. Three years later, he was dead.

In 2004, two years before his death, he published his memories under the title My Father, Il Duce. He describes his mother’s suicide attempt, which he witnessed at Villa Feltrinelli as a 16-year-old.

Rachele Mussolini knew that her husband had been having an affair with Clara Petacci for many years, but when the adultery started taking place in front of her eyes, from 1943 onwards, she had a nervous breakdown. Her driver took her to Petacci’s home in the Villa Fiordaliso, where she demanded that her rival disappear from her husband’s life. But Petacci refused. After returning to the Villa Feltrinelli, Rachele Mussolini locked herself in the bathroom and drank bleach. A maid found her unconscious and called the doctor, who saved her life. After the war, she opened a small restaurant in her hometown of Predappio in Emilia-Romagna, which became a site of pilgrimage for fascists. She died in 1979, at the age of 89. It isn’t known whether she ever went back to Villa Feltrinelli after the war.

In 2007, Robert H. Burns sold Villa Feltrinelli. Why?

He became a father for the first time, at the age of 70. He wanted to raise his son in New York and Hong Kong, where new hotel projects were calling.

Roman Abramovich wanted to buy Villa Feltrinelli but lost in the bidding war. The hotel’s new majority owner is said to be the Russian oligarch Viktor Vekselberg, head of the Renova Group, which has company holdings everywhere from Siberia to California. According to Bloomberg, Vekselberg is the 115th-richest person in the world. Your employees say that he bought the villa to give to his wife as a birthday present.

Just a few words on this: the new investors enable us to run the hotel to the same standard as before.

The Villa Feltrinelli only has 20 rooms, making it the smallest Grand Hotel in the world. There are 80 employees for a maximum of 40 guests. Are you expected to make a profit despite this ratio, or is your house more of an expensive hobby for the super-rich?

We’re a for-profit operating company, not a hobby.

A stay with you costs between 1,600 and 5,500 euros a night. Guests must book at least two nights to be accepted. What other extravagances do clients who can pay those prices allow themselves?

Thousands of flowers bloom in every color on our grounds. Once a guest who was hosting his daughter’s wedding wanted us to tear out all of them out and replace them with 8,000 white begonias. After the wedding, he also paid to have the colored flowers replanted. Another guest, from London, once asked me to buy a 25,000-euro mattress for his four-day stay with us. You might find this eccentric, but the guest said he wanted to be just as comfortable in a hotel as he normally would be at home – and at home he slept on a 25,000-euro mattress.

Your guests run up steep room charges [while] tending to their extravagant wishes – some have spent 2 million euros in one stay. Are there any desires that you remember being particularly expensive?

Private concerts by Al Jarreau and Rolando Villazón, and a performance by Cirque du Soleil in our park.

Have you ever failed to fulfill any requests?

We see ourselves as being a cradle of intimacy, so we only allow events with up to 40 guests, no more. We would never dream of setting up tents in the garden. It isn’t possible to book 10 rooms with us, either. That would create a group of 20 people, which would make the other 20 guests feel like they were second-class.

“All’s good if it’s excessive.”

– The Bishop, Salò

Is there anyone who cannot book a room with you?

Anyone who has an obsession with Benito Mussolini’s person.

Your guests include the usual suspects: Julia Roberts, Hugh Grant, Richard Gere, Tina Turner, and Amal and George Clooney. Aren’t the celebrity egos an annoying imposition to some of your other guests?

In general, the people who come to us seek an oasis for recovery and do not need to be seen. They enjoy the fact that we only allow hotel guests to enter the premises.

You’ve also hosted celebrities known for the occasional public outburst. Have you ever had to make a call about who can stay and who must go?

Not once. Beauty and style have a calming effect on people. No one would think of yelling at an employee or throwing the television out of their room window. Even Goethe already knew that beauty is calming.

Does old money behave better than new money?

Some like to think so, but no, there is no difference.

Are there any services you offer that other high-end hotels don’t?

An example: we have regular guests who leave everything behind when they depart – from a tailored suit to a half-empty tube of toothpaste. The next time they come to us, we’ve hung the dry-cleaned suit in the closet and purchased a new tube of the same brand of toothpaste. When these guests leave, their rooms are photographed, since everyone has their own ideas about tidiness. Their things are stored in our depot. When the guests return, their room has been prepared according to their preferences. You may have seen that a helicopter landed in front of a guest villa today at noon. It delivered a couple who stays with us several times a year. I know the two of them inside and out, from their taste in flowers down to their preferred pillow filling. She likes to have a small make-up mirror on the night table for when she takes her contact lenses out at night. He likes to have his favorite wine in the minibar. People love to return to a place where they are remembered.

You prefer to hire custodial and service staff who do not come from the hotel industry. Why?

The decisive criterion for us is that the employees have the right attitude. You can teach people many things, but you can’t teach the desire to serve. We train every employee to respond to a guest’s body language, which requires intuition and empathy. Our most important message to our employees is: please run this house as if it were your own hotel!

Are the salaries adequate to keep up with your job description?

Yes. Part of our concept is to pay far more than what is standard. We add a service surcharge of ten percent to the room rate, a surcharge that is then evenly distributed amongst all employees. As such, all the employees one doesn’t see, who work in the laundry for instance, get their due. There is hardly any turnover with our staff. That’s a great compliment for any employer.

After 20 years of service as the director of Villa Feltrinelli, you must be an eminent authority on the psyche of the super-rich. What have you learned?

First of all, that you don’t recognize the people who are really rich because they hardly ever appear in the media. They frown upon snobbery and ostentation as much as they do on conceit and decadence. Also, our guests don’t pay attention to what others are wearing. The wealthier the guest, the smaller their luggage. Ultimate luxury is synonymous with simplicity. The trick is to make the decisions for the guests. A waiter does not need to give a lengthy explanation about the ten brands of mineral water that are available. He has already memorized what brand you prefer. This allows the guests to catch their breath, since they need to make decisions all the time in their jobs.

What annoys you when you stay in other luxury hotels?

When I’m robbed of time for no reason, or when I become victim to stubborn procedures. I often find that I’m charged for the quick espresso I order while waiting for a cab after checking out of luxury hotels. Doesn’t a certain amount of generosity belong to a certain category, such that you aren’t charged for little things like espresso? Excellence in service also means being casual about the rules.

In 1898, César Ritz, the youngest of 13 children and a shoe shiner as a boy, came up with a mantra for his ultra-luxe Hotel Ritz: “If you don’t move with the times, you’ll get left behind.” What needs to change at Villa Feltrinelli?

Giangiacomo Feltrinelli was a heavy smoker who hardly did any sports. Our guests today, however, mostly want to start the day with a workout. Since a fitness studio wouldn’t fit the character of the villa, we are going to equip a building across from us with the very latest sports equipment so our guests can work out in a modern environment. You see, we’re moving, but the direction has to also be in harmony with our history. And it would tear the soul out of the villa if I put minimalist designer furniture in the lobby.

The smartest thing ever said about Grand Hotels?

Lampedusa wrote it in The Leopard: “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

Credits

- Text: Sven Michaelsen

Related Content

FRANCESCO VEZZOLI: Plastic, Saturday Night, Milan

ROT THE MAP: LIZZIE FITCH and RYAN TRECARTIN’s WHETHER LINE at the Fondazione Prada

LA DOLCE VITA: “Can Such Things Be?”

The First Fashion Blogger and the Dandy Ethic of Capitalism

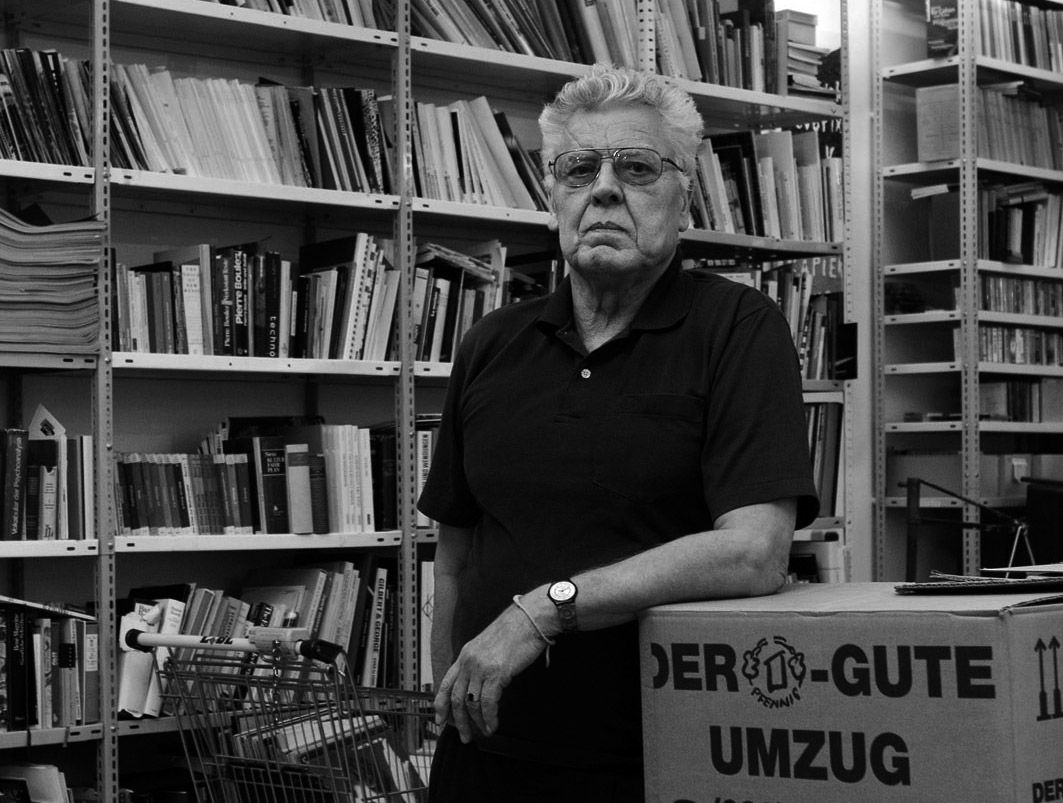

We Salute PETER GENTE (1936–2014)

Grin and Bear it: Leisure and Terror Vacation in the Weimar Republic

PHILIPPE HALLAIS: An American Hero