The First Fashion Blogger and the Dandy Ethic of Capitalism

In the current age of hyper-minimalism—where austerity has become the de facto metric of good taste—findings from pre-modern Germany reveal a lost mode of ornate masculinity.

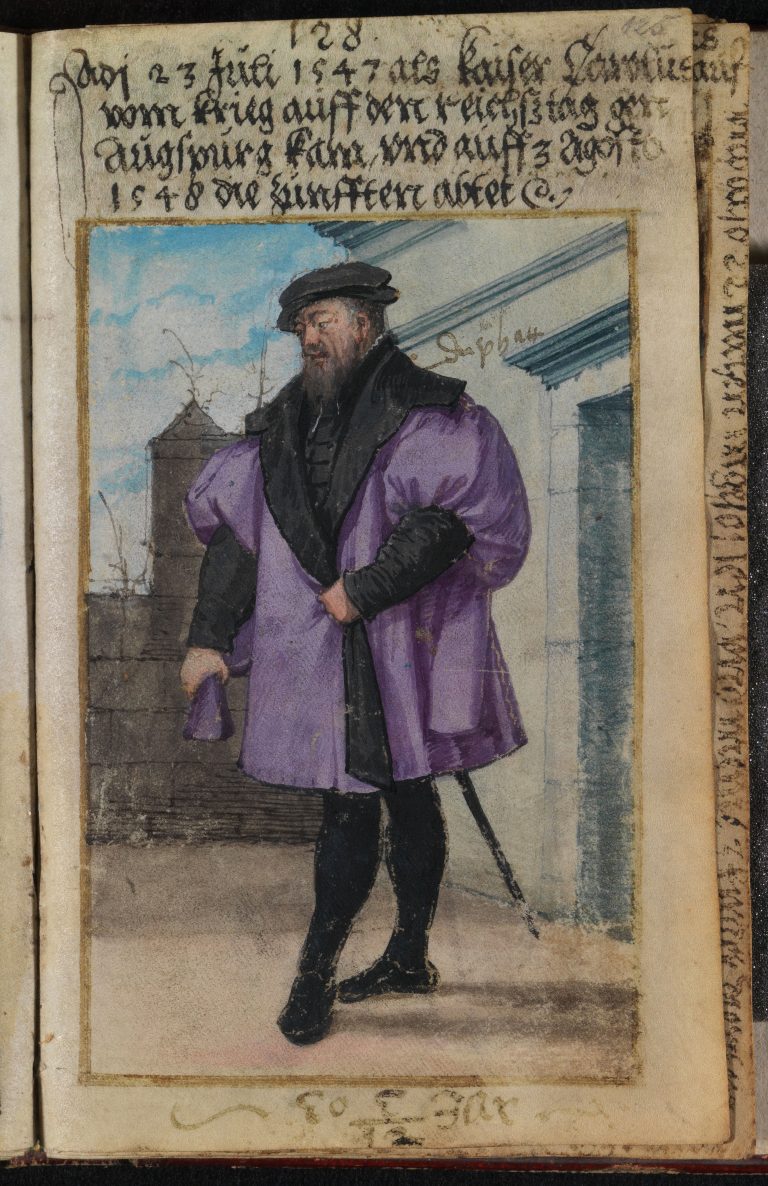

Unearthed after centuries in obscurity by historian August Fink in 1963, and published now for the first time in color, The First Book of Fashion documents the life of Matthäus Schwarz through his obsessive relationship to clothing. Schwarz was an accomplished eccentric. As a financial advisor employed by the notorious Fugger family, he is the only accountant to have his portrait hanging in two major museums (including the Louvre). He also claimed to be the first person to have celebrated his own birthday. Along with local artist Narziss Renner, Schwarz embarked on a 40 year project to document his sartorial choices in meticulous detail.

Schwarz’s book of illustrations is a unique fashion document, but also an artifact of a strange moment in history. The accountant was born in Augsburg in 1497, during a time when the gushing excess of newborn capitalism had not yet been reigned in by protestant notions of self-restraint. In many ways, Schwarz was the first of his kind, a proto-yuppy who pre-existed the humble and Lutheran norms of bourgeois living. The First Book of Fashion showcases Schwarz’s loudly-colored doublets, his heart-shaped coin purses, as well as his scarlet bonnets with gold buttons and threads. The display unveils a frozen strain of ultra-flowery masculinity that is still powerful nearly half a millennium later. While Schwarz has been called “the first fashion blogger,” it would be more accurate to compare his project to the #OOTD (Outfit of the Day) Instagram tag. By focusing on his changing wardrobe from adolescence to old age, he prefigured the mode of autobiography-as-art.

The recent exhibition “In Mode” at the Germanische Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg focuses on clothing in a similar time and place as Schwarz. Centered around archeological findings from a tailor’s studio in Bremen, the show brings into light other episodes of renaissance and early baroque fashion. Installed in a floating, phantasmagorical style, the remnants on display appear as unraveled strands of our current sartorial DNA. One such example is the practice of “pinking,” a decorative technique of ripping small slits in a garment. Much like pre-distressed denim, pinked tops were an aristocratic sign of reckless bravado, one that gradually got more and more extreme. Matthäus Schwarz himself owned a doublet with 4,300 tiny pinks. But as the trend morphed into jackets with large, gaping slashes, the power of the state began to intervene. In 1529, a member of Swiss parliament ordered everyone who owned ripped clothing to either throw the garments away or sew the cuts back together.

While certain findings from this time are oddly familiar, other extravagant mutations have become extinct and seem alien to us—silky balloon-shaped silhouettes, pleated variations on the man skirt, and hats that dwarf Pharrell’s Vivienne Westwood chapeau. But perhaps the most bizarre of these relics is the ruff, an iconic Elizabethan neck-ssessoire. The ruff collar is a prime example of fashion’s penchant for absurdity. The neck device, made of starched linen or silk, was often embroidered with pearled lace and folded in figure-eights. Its design created the illusion of a floating head, the Cartesian separation of mind and body realized as a style affect. Such a head feels precarious perched atop its silk saucer, as though the ruff presupposed the slice of the guillotine blade and the imminent demise of bloated baroque culture. Yet viewed from the perspective of the present, the ruff is a spectacular triumph of decadence and body modification. In the current epoch bound in denim and shoved into sleek workwear silhouettes, this maximalist notion of the dress exemplified by Matthäus Schwarz and his contemporaries reveals the curious power of pure and unabashed ornament.