Grin and Bear it: Leisure and Terror Vacation in the Weimar Republic

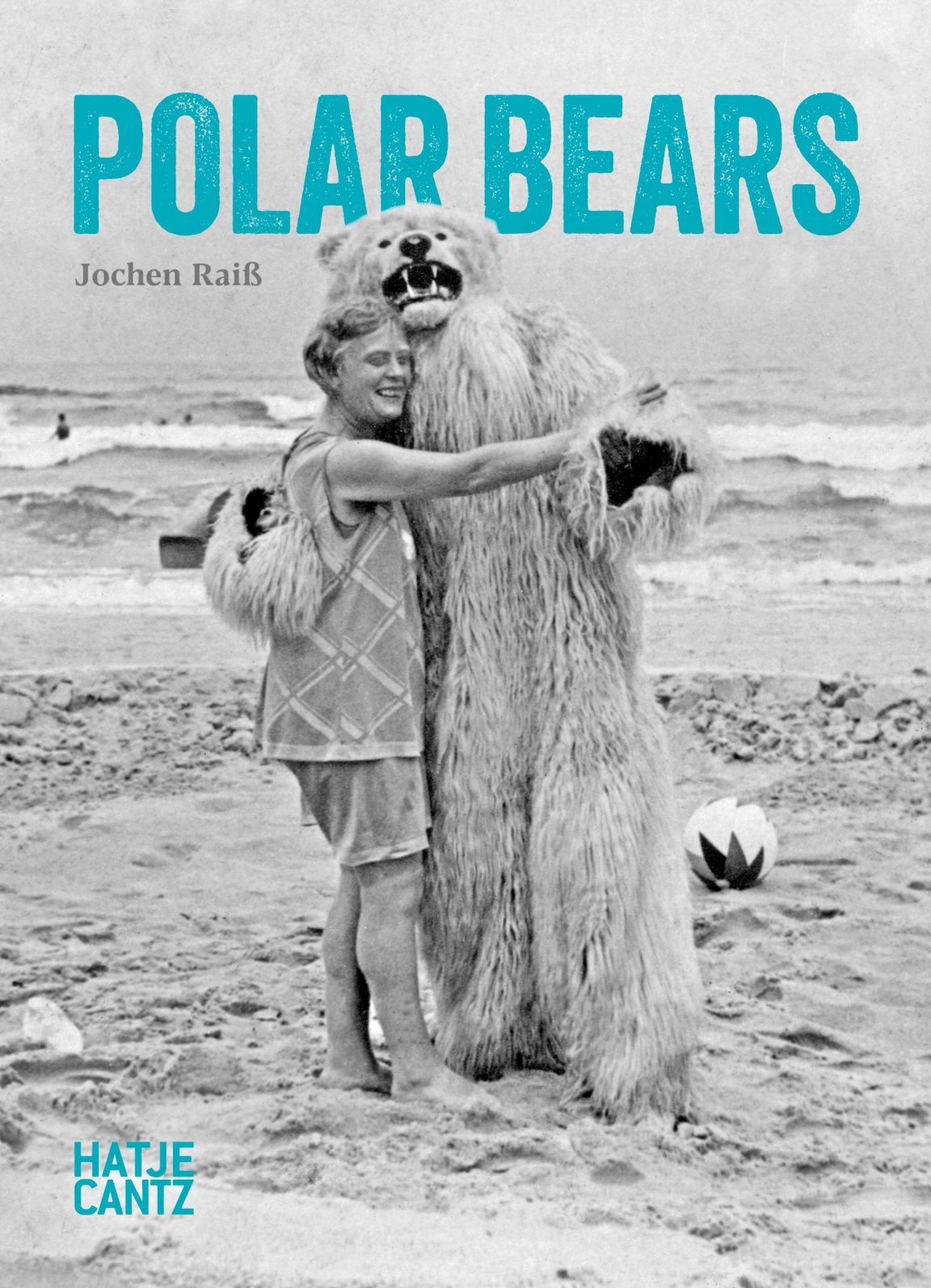

Much of the northern hemisphere is preparing for an “Arctic blast” this week, and it’s already snowing in Berlin – which, naturally, causes our minds to wander away from our desktops and toward our favorite winter leisure-themed Hatje Cantz publication: Polar Bears, edited by collector Jochen Raiß and reviewed by Philip Maughan for 032c Issue #37.

A searing cause célèbre in the global news cycle of the late 2000s involved an infant polar bear named Knut who was rejected by his mother at the Berlin Zoo. Animal rights activists declared the helpless cub would be better off euthanized than raised by humans, and groups of school children took to the streets in opposition. The bear became a proxy for talking points from animal domestication to the perennially broke German capital’s improving fortunes. Knut liked to eat croissants and was photographed by Annie Leibovitz. When he died, aged four, after drowning in his enclosure, his pelt was used to cloak a sculpture at the Natural History Museum. It’s still there.

In 2008, the toy manufacturer Steiff created a line of plush Knut dolls in collaboration with the zoo, though the company had been making stuffed Eisbären (the German name literally means “ice bears”) since at least 1912. It has been posited that Steiff’s ensuing publicity campaign was the root of a micro-trend beginning in the Weimar era, in which tourists were photographed with polar bears – or, more accurately, with men in polar bear suits. Photo editor Jochen Raiß has been collecting prints at flea markets and grouping them under unusual motifs for over 30 years. This habit has already produced one book, Women in Trees (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2016), but Polar Bears seems to hint at something more distinctive: an ambivalent arrangement of leisure and terror that occurred in holiday spots from the Baltic coast to the Alps, but seems not to have become popular outside Germany.

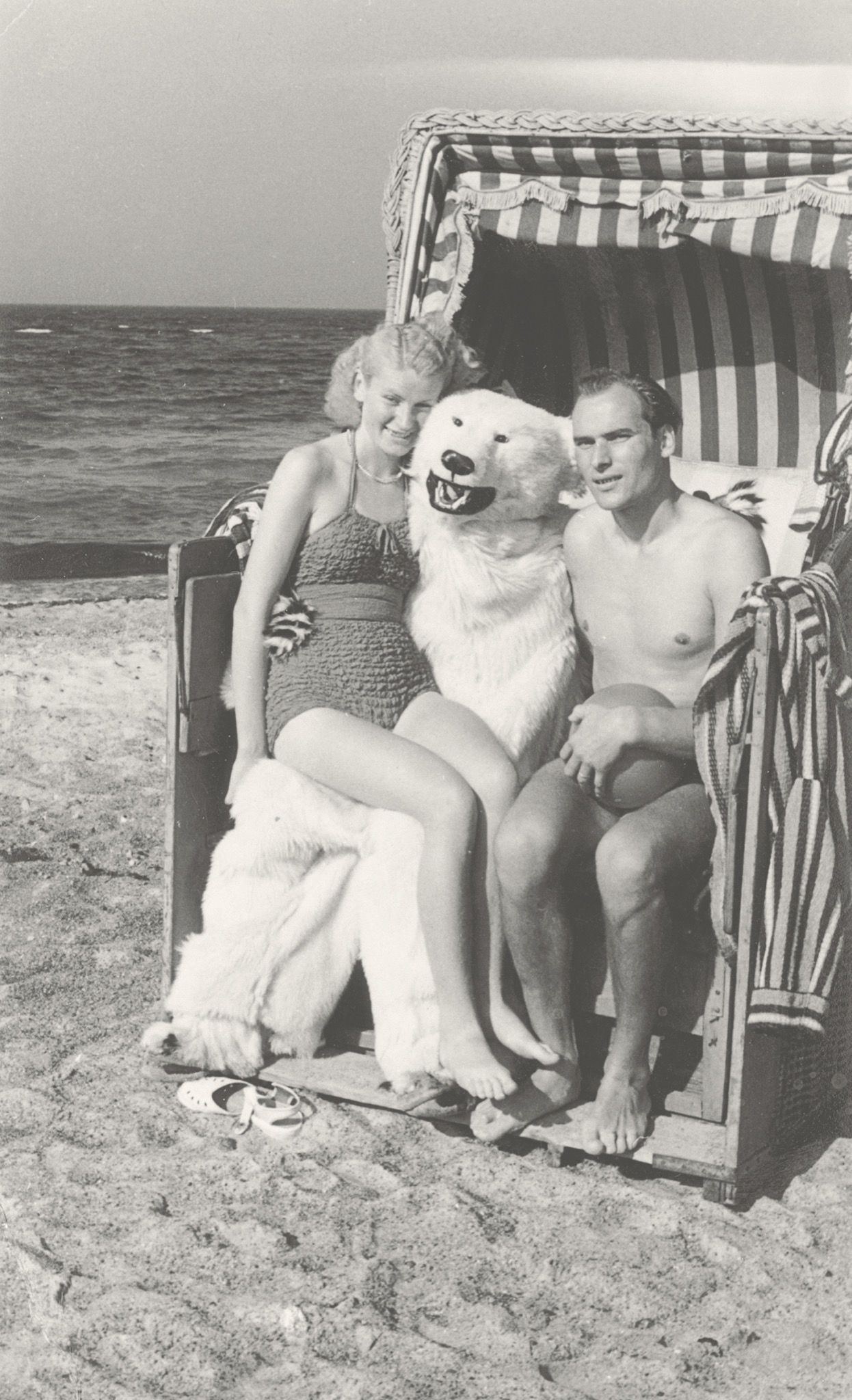

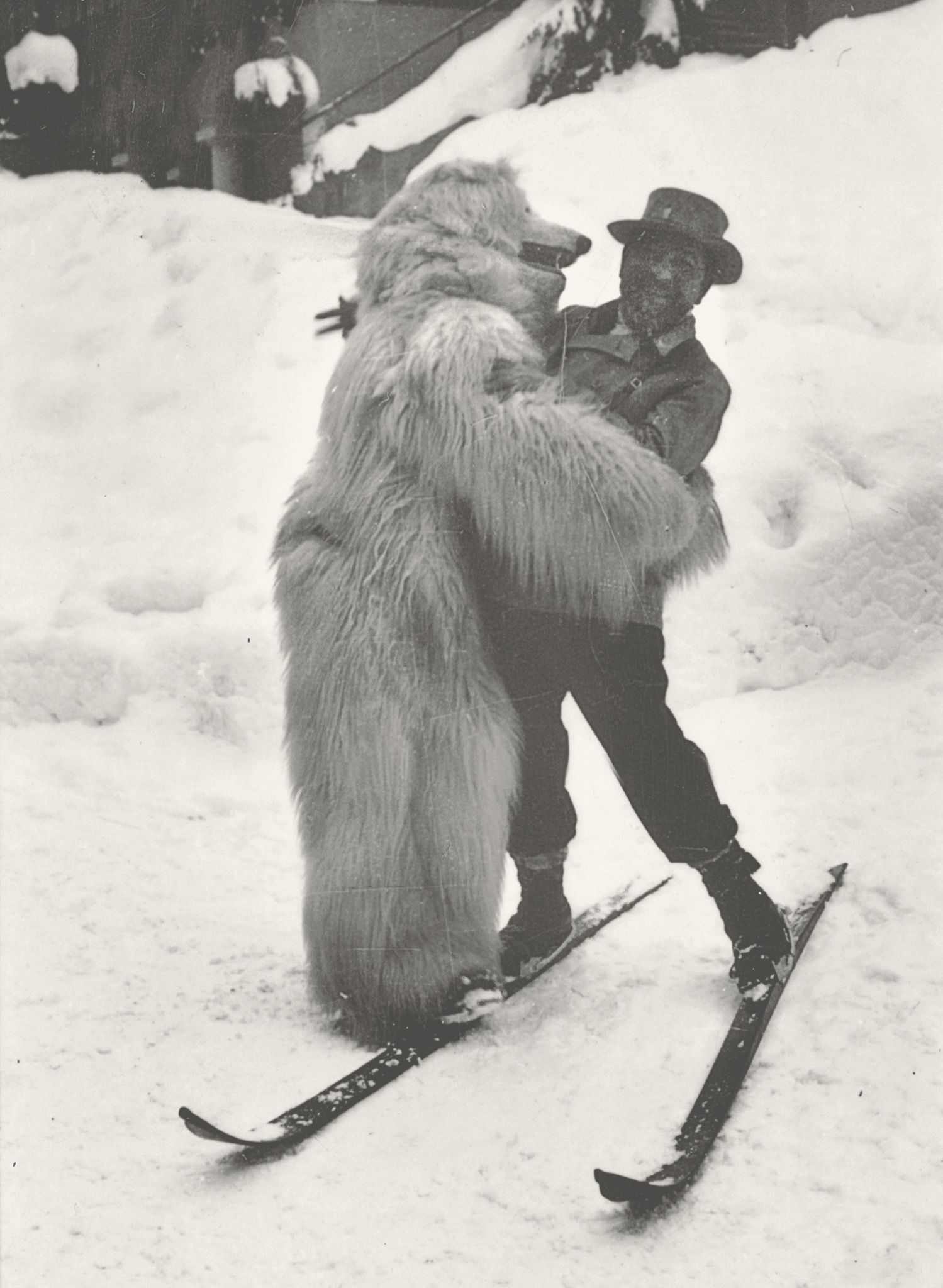

So what is it about polar bears? If it wasn’t successful market penetration by Steiff, perhaps it was the work of a hustling photographer that triggered the analogue meme. This is the theory supported by Raiß, whose book is dedicated to the anonymous figures “who wore these costumes.” In the first half of the 20th century, bear skins were emblematic of luxury and exotic danger. Hunted to extinction in Germany in the 19th century, they were already figures from the past. In one photograph, an elegantly dressed woman appears to flee, though it’s not clear if the tableau is staged, or whether it’s the beast or the opportunistic grifter inside that she’s trying to escape. Elsewhere, in small group photos, the bears seem superimposed: rarely the photographer’s focal subject, they are interlopers lurking in the background. It only takes a fall in blood sugar for the grinning, unlikely polar bear at the beach – pushing strollers, playing tug-of-war, pawing at bikini-clad women – to take on a sinister note. Who is the man in the suit, and does he belong in the picture any more than a polar bear belongs on a chaise longue?

Since the 13th century, the bear has been Berlin’s heraldic mascot, appearing on everything from parking tickets to beer bottles. Some say the reasoning is nothing more than a homophonic pun on the city’s name, while others claim that Berlin was named for its ubiquitous Bär, not vice versa. The bear is a paradox, a cuddly killer – an appropriate projection for a civil administration that aims to convey both dominion and hospitality simultaneously. The associative power of polar bears, however, is more complex. In Inuit and Alaskan mythologies, polar bears were shapeshifters who turned into human beings in their caves. Arctic peoples are believed to have adopted hunting methods from polar bears, and see kinship with them due to the species’ intelligence, anthropomorphic postures, and a shared dependence on ice.

“Knut is a symbol for our battle against climate change,” Germany’s former minister for the environment Sigmar Gabriel told the world in 2008, explaining how he hoped to transmute the media frenzy over the cub into progressive action. It hasn’t happened. Polar bears are a spectral presence in Raiß’ images, a ghost at the feast, and a transmission that we continue to struggle to decode.

Credits

- Text: Philip Maughan

- All Images: courtesy of Polar Bears ©Jochen Raiß