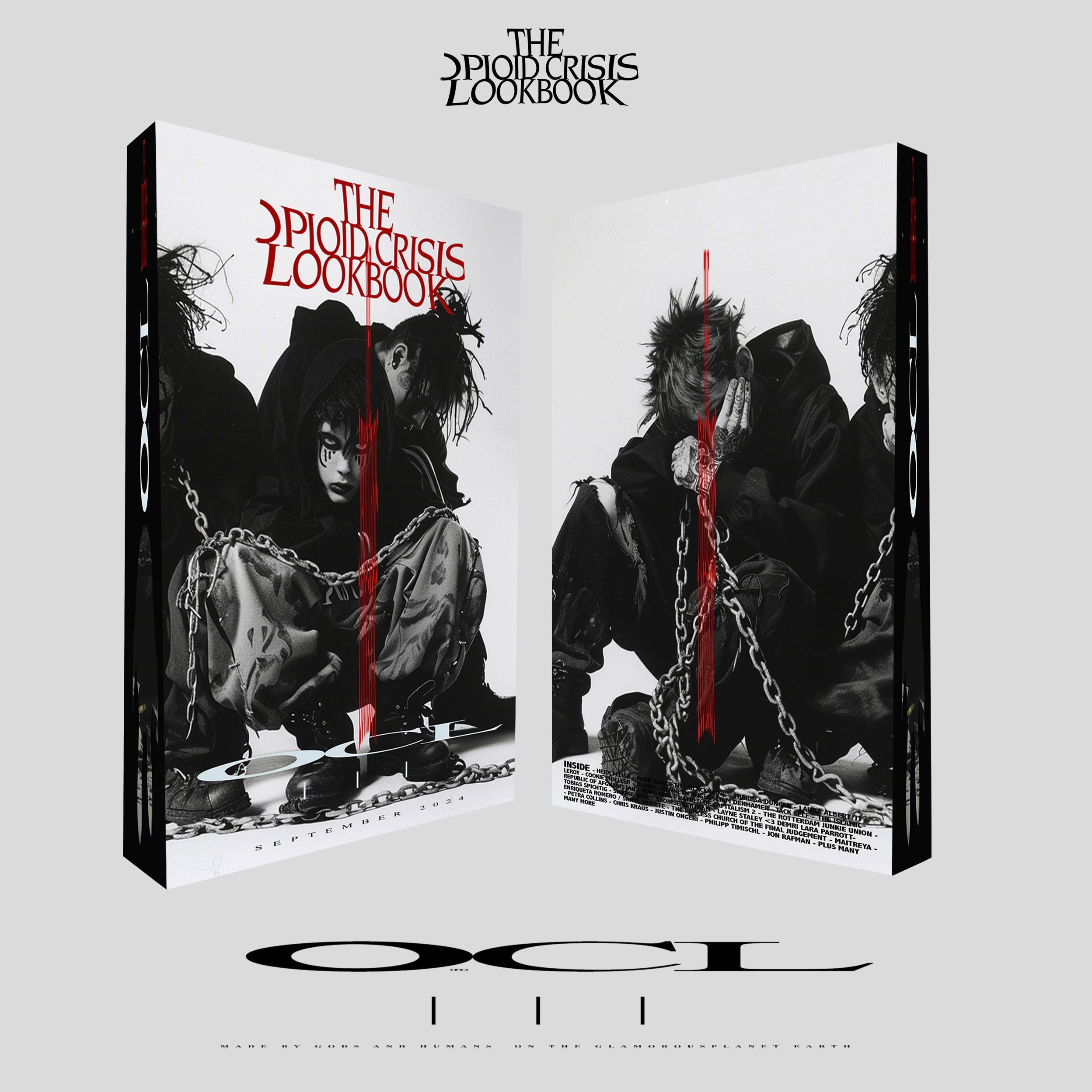

The Opioid Crisis Lookbook: An Interview with DASHA ZAHAROVA and DUSTIN CAUCHI

|CASSIDY GEORGE

The opioid crisis has killed more than 560,000 people in America. Today the number of annual opioid overdoses is more than eight times higher than what it was in 1999. As cities and states are devastated, the government has passed bills and ramped up medical support, but also to no effect. Perhaps what is needed is another response to the crisis – one that raises awareness not only about synthetic drugs like fentanyl, but also about those suffering from addiction.

The dossier in 032c Issue #45 was created by DASHA ZAHAROVA and DUSTIN CAUCHI, the editors behind the Opioid Crisis Lookbook: a magazine about drug addiction and its systemic, aesthetic, and cultural implications. OCL depicts the horror of the crisis, creates empathy and contextualizes it in a jokey, meme-like way, showing that the magazine isn’t “pure gloom…[but] is also beautiful, senseless, funny… and a weapon of empowerment.”

Earlier this week, OCL released their highly anticipated third issue, which will be accompanied by launch events in Paris on October 18 and Berlin on Nov 1. “If OCL Issues 1 and 2 brought awareness of the unfolding opioid crisis and the rising fire, Issue 3 promises enlightenment and ultimate freedom,” Cauchi writes in Issue 3's introduction. Most of the magazine was, according to Cauchi, "imagined in a small room in the Raval district of Barcelona where Dasha and I lived out our neo-grunge fantasy on a mattress on the floor, sky-high or dope sick, time incalculable.” OCL Issue 3 includes contributions from various 032c veterans, such as Chris Kraus, Petra Collins, Blackhaine, JT Leroy, Jon Rafman, and Jack Self.

On a sunny day in late Spring, Zaharova and Cauchi invited 032c reporter CASSIDY GEORGE to their flat in Neükolln. In a rare interview originally published in 032c Issue #45, the couple spoke for the first time about how they fell in love, what they mean by "speculative semiotics," and why they joined the Santa Muerte cult in Mexico.

The Opioid Crisis Lookbook Issue 3

CASSIDY GEORGE: How did you two meet?

DUSTIN CAUCHI: It’s a long story.

DASHA ZAHAROVA: It’s the greatest love story.

DC: And after we met, we never parted.

DZ: We were married in New York, on Halloween.

CG: You haven’t addressed being a couple in past interviews. Was that intentional?

DC: We refused a lot of interviews. It wasn’t the right time to talk about ourselves.

DZ: We also needed to protect ourselves.

DC: In the beginning, it was important that the project wasn’t about me – that it could exist almost independently of me. But Volume 3 of OCL, which we have been working on for three years, is very autobiographical. It’s very important to us that there’s no separation between what we do and how we live.

DZ: We’ve been through a lot, and that always translates to the issues.

CG: Can you offer some visibility into the production process?

DC: In the beginning, I did everything, but Dasha became increasingly involved and became an editor very naturally. It wasn’t planned. She definitely has her own style, which I really like. Everything is sourced based on a feeling, which can be aesthetic or not. It can be a color, a sound, an idea. Then we alter it with our own process. The image eventually becomes something entirely different, and it’s no longer recognizable. It becomes devoid of its previous meaning or sometimes augmented or exaggerated. We also work with a lot of dynamic texts. Some we ask permission for.

CG: I laughed at the David Foster Wallace text that you warped and included in OCL Volume 1. You made it very clear at the top of the page that you did not get permission for that text.

DC: We really tried to get permission!

DZ: No, we didn’t!

DC: Okay, we sent two emails. And then we sent a friend knocking on their door. That sounds like trying to me.

DZ: At this stage, everything can be used – there’s really no reason why it shouldn’t be. Once you change an image or a sentence – or put two things together from a different time, the meaning of it completely changes. Most images that are produced today are really flat.

Photograph by Tobias Spichtig.

DC: Our way of making images is similar to a painterly process, but with a screen. We mainly use Photoshop as a tool, but we also physically alter images. We paint on them, chemically manipulate them, and then scan them, add text. I’m currently developing a concept called speculative semiotics. It will eventually become a philosophical concept, and it’s the machine that runs everything we do. The idea is very simple: to deliberately reorganize signs and symbols to create new meaning. Every time that we have appropriated something, the people who made the original ended up loving our version.

DZ: People also feel extremely empowered by what we do I think because of the simplification. We always want to give space to marginalized voices and narratives.

DC: That’s why I started OCL. I have a history of addiction, so what was happening in the US with the opioid crisis in the late 90s and the 2000s was important to me. My first impulse was to document it and to give voice to cultures that were born out of the crisis, and amplify stories that were sidelined by headline media. This was the original focus and spine of the project: to give a voice to people on the streets in the US. Some voices are not understood, and I speak as [such a] person. We get sidelined because someone doesn’t understand us, or because there’s an agenda. What people don’t understand, they put aside.

DZ: I come from a background of global economic and systematic governance. I have always been able to see the global structural factors behind things that cause crises. Dustin and I are always saying the same thing but from different perspectives. We collectively think about and have experienced these structural factors that have caused pain and certain kinds of suffering. When voices are sidelined, no matter who they are or where they come from, there is a kind of understanding there—a shared language—of something that causes damage.

DC: It’s not that we love pain, it’s that pain is a bridge that makes experiences more universal.

DZ: Pain makes it easier to empathize with others. It breaks down social and cultural presets and causes collective change. Empathy gives us the chance to undermine and change the realities and structural factors causing suffering that are imposed on us.

DC: The system that governs us won’t go on forever. The party is soon over. There are so many people suffering, especially in the US – but that can be changed. The minority is growing and will eventually no longer be a minority, [if,] instead of hoping for a better political condition, we just focus …

DZ: … on internal changes, and empathy is the tool that allows us to move forward. We can already see it in response to the magazine. Our readership is a lot of teenagers from all over, but moms also love it. They send messages to the account that say how much they appreciate what we are doing, and how much it gives them hope.

Photograph by Tobias Spichtig.

CG: When you’re doing something like this, you have the power to create very intimate connections that are [based not only] on appreciation but also on shared suffering. Is receiving all of those messages ever too much emotional labor?

DZ: I mean, we’re so emo it hurts. And receiving messages like that makes it all [worthwhile]. Because you’re doing something that you realize is no longer just in your head. It’s out there, affecting real lives. The culture and the conditions this crisis generates are unprecedented. It’s an exciting and scary time, and we’re documenting it.

DC: We are committed to experience and feel stuff intensely, instead of just speaking about it. We are also helping to create it without colonizing it – because we are also part of it; it is also our culture.

DZ: We just want everyone to feel better and go through these changes without repeating past mistakes. We want to rebuild something that can be shared, and not just perpetuate power play. There are so many things wrong with the world, for so many ridiculous reasons. Even normal people who are still infatuated with the reality imposed on them are feeling some sort of necessity for change or can at least feel that something is really wrong. It’s not just about the opioid crisis. There are thousands of terrible consequences playing out for the same reasons, which is that they benefit the interests of the same people.

DC: Then again, we are really hopeful. Because if there’s anything history has taught us, it is that change is a natural constant. So, it’s simply a question of time. That’s how we see our role, not just as precipitators of change, but also as advocates of change, clearly saying that change is possible, that there is still hope.

DZ: Chaos without violence.

DC: Hopefully … without violence.

DZ: The rise of the beaten and the damned.

DC and DZ: The black parade!

CG: Have you already set your sights on exploring new terrain, new kinds of media, or new forms of exhibition for OCL?

DZ: We want to change a lot of things. If something happens, it happens on our terms—and it’s not the normal way of doing things.

DC: Creating something new is always challenging and takes time, but we are lucky to get a lot of support from people … you might not expect.

CG: As in, more traditional institutions?

DZ: Yes, but also individuals.

CG: You also make and sell merch, in addition to the publications, correct?

DZ: We do, but everything is really limited, even the OxyContin soft plushie toy. In the 1990s, Purdue Pharma used to promote OxyContin with gifts, and one of these gifts was this ugly-ass blue soft toy, and they used to give it out for free. We reproduced the plushie ourselves, then did an edition with Praying that sold out.

DC: We sell out [of] everything. For example, at one event in New York City, we ended up reselling single pages of Issue 1 because they are so rare that people were happy to buy a page out of it.

DZ: We could make a lot of money if we wanted to, because people constantly want to buy things from us.

DC: We have nothing against money or money-making. But we want to remain credible to ourselves. Last year, we founded OCL Studios, where we do commissions and commercial works. One of the studio’s first works was the editing and graphic design on Travis Scott’s Utopia zine, a publication that accompanied his latest album.

DZ: Sometimes we collaborate with brands we like. But what we are making together is art. We are not a magazine that makes money off brands and advertisers.

CG: Dasha, you’re wearing head-to-toe Praying right now, though. It looks like an advertisement!

DZ: Yes, they just sent us a bunch of stuff. They’re really good friends!

DC: We not only like them as friends, but we think that what they do is important. We’ve been supporting each other since the beginning.

DZ: It’s really hard for OCL—but also for brands like Praying – to find a path that has not already been established.

DC: Praying … found a new way of being a brand, and of playing with what it means to be a brand. It’s something we support as a concept. We also like working together, and we are working on a capsule collection inspired by grunge, or grunge chic. But we don’t do tributes, so we’re trying to find different ways of reviving it.

CG: It’s crazy to see how big this crystal meth heroin/post-internet/OG Kelvin filter/deep-fried meme aesthetic is right now, even in the poppiest of pop culture.

DC: OCL has been a moodboard staple for a while now.

CG: Have some of the fashion houses reached out?

DC: Yeah, of course. We weren’t very nice to them in the beginning. But over time we [saw] the positives in such a situation. Also, you know, with the mask-faced aesthetic. This “scary” aesthetic has become the look of a number one musical artist. It’s great, I think. This amplifies our voice in a way, and, in doing that, amplifies the voices we represent on a scale that we can’t.

DZ: At one point, our aesthetic was very masked robber and black metal. You can see traces of it everywhere. At the moment, our style is really enlightened.

DC: Like grunge enlightenment. I actually don’t even know how to describe it; we are still finding a way to articulate it.

DZ: Me neither, but they will find a title for it.

CG: With your Instagram account, how do you navigate community guidelines? Have you ever had your account suspended or deleted?

DC: We’ve never been reported or had a problem. Our audience loves us. There are also ways to navigate it. For example, syringes and pills are okay to post – unless there is nudity.

DZ: But we’re shadowbanned as fuck.

CG: That additional barrier to entry might actually be helpful to the project.

DC: I think it is. It’s funny, because some people we meet speak to us as if we are famous, but we only have 14,000 followers. If it grows too much, we will probably have to stop the IG account, as it would start meaning something entirely different.

DZ: We don’t only want to speak to a specific group of people, or to make something directed toward a group of intelligent or cool people. Once you do that, you’re no longer part of the real world.

DC: You know Meg Superstar Princess? She’s one of our editors and also one of our best friends.

DZ: She brings in a lot of people that we can’t necessarily reach, because we don’t live in the US. She incorporates these voices that are particularly American and are beautiful manifestations of the gritty current condition. There are so many new things and subculures emerging, and Meg documents all this and helps create and nurture it. One night a couple of months ago, the three of us were together with a very special friend, Bobbi, and we decided overnight to do Trainspotting the musical – or the play, or whatever – in Brooklyn.

CG: Really? I didn’t see any promo or documentation.

DC: There wasn’t any. We kept it secret. But there must have been a thousand people there; it was packed. We did it at Bobbi’s home. There is a stage of sorts at this squat. We created a script of passages ranging from Batman, our writings, and lyrics, to various philosophical texts and poems. I didn’t even know the sequences, we just handed them out to “method actors” Meg, Dasha, and Bobbi as the play progressed. They read them, and it became a kind of performance through repetition.

CG: There seem to be a lot of physical manifestations of this project that are easily overlooked, if you’re only accessing OCL online.

DC: Even though most things are secretly available in various online locations, very few people have seen the physical images, held the actual magazine, or attended a live event.

DZ: The magazine is the rarest thing, though.

DC: I’ve seen them on ABE Books [a site aggregating literary rarities for sale], regularly fetching 600 euros.

DZ: Issue 1 sold for 5,000 euros on eBay.

CG: You’re in Berlin right now, but where are you normally based?

DC: We have been all over but have an apartment in Malta. We’ve also been in Barcelona off and on for … years.

DZ: These are places where we go to hide and work. We need a lot of stillness to sit down with everything we have collected and work on the magazine.

DC: Malta has been good in that way. Riding bikes, chilling at swimming pools, going to temples, reconnecting with nature – that sort of thing. We don’t have distractions.

DZ: Dustin’s place there is really nice. He has a huge library.

DC: We’ve also collected so many things over the … years. So, Malta is also a safe house to stash.

DZ: It’s this mass operation in our lives. Collecting can consume your soul.

DC: We collect music, books, clothes, but also esoteric things, magick stuff like Santa Muerte statues from Mexico. We traveled there recently to meet the guardian of the Temple of Santa Muerte, Enriqueta Romero. It used to be an underground cult, but Enriqueta opened her home in the late 90s and made it a public sanctuary, the first of its kind. This was a huge thing, as the cult is still [persecuted] by the church and the state. When we were in Mexico City, she initiated us into the cult and gave us a great interview that will be in Issue 3.

DZ: In many cultures, people are devoted to a figure of death or some kind of power for protection. In Mexico, the Santa Muerte figure is a very powerful symbol and has a very powerful presence, particularly because Mexicans have a history of natural magic in their blood. This used to be the case everywhere in the pagan world. Christianity sadly wiped out most of these beliefs and rituals, but not all. Part of it still lingers, and the Santa Muerte figure is this merging of magic and occult beliefs with Christianity.

DC: At first, the figure was masculine – but over time it evolved into a mother figure. We attended the initiation ceremony with thousands of cartel people. It was wild.

DZ: Cartel people are mostly devotees. They seek protection, as death is part of their daily reality.

DC: This woman is the closest thing to something holy that we’ve ever encountered.

DZ: She’s really a saint.

CG: Can you maintain contact with her now that you are no longer in Mexico?

DC: We write to her. We’re also interested in helping her refranchise and update the aesthetics of the cult. I love the classic aesthetic, but I think it could reach more people if it was a little bit cooler and slightly less scary – because it’s quite scary. That’s just how people live in Mexico. All throughout the country, you see there’s another dimension—and that there’s no real separation between dreaming and waking life in their cultural consciousness. It’s not just a cliché, it’s really like that in Mexico.

CG: So, OCL is now doing creative consulting and brand management for cults?

DZ: Yeah, exactly.

DC: I think that’s the perfect job title for us.

Credits

- Text: CASSIDY GEORGE