ROBERT SMITHSON is the Missing Link between MINIMALISM and PSYCHEDELIA

Early pictures by the post-minimal sculptor reveal the pulverized pop within supposedly austere works such as Spiral Jetty.

While the late 1960s are fondly remembered for their “peace and love” mantra, it is often forgotten that the hippie movement’s legacy is most visible in its occult by-products. Every dose of LSD promises either bliss or a bad trip. Which is to say that spiritual purity and black magic are inherently intertwined. Take the teenage runaways turned perma-dazed hippies who Charles Manson recruited to form his family. Like millions of their peers, they sought a brand of personal freedom washed in psychedelic guitar riffs, but somehow they ended up with Helter Skelter. In a similar stroke of irony, Robert Smithson is often recognized as a sculptor most famous for his post-minimal land art that is both authoritative in its scale and mysterious in its prehistoric appearance. Yet his early works on paper, displayed in James Cohan Gallery’s catalogue Pop, reveal his status as an archetypal post-60s artist. While iconic Smithson works such as Spiral Jetty (1970) and their primordial, Stonehenge-like aesthetic somewhat romantically study America’s nature, they also reflect its cultural-psychological state at a particular time. Their austere surface hardly gives away the nebulous path Smithson took there. Within the dirt of these hippie-minimalist gestures lies the pulverized matter of Smithson’s contemporary influences.

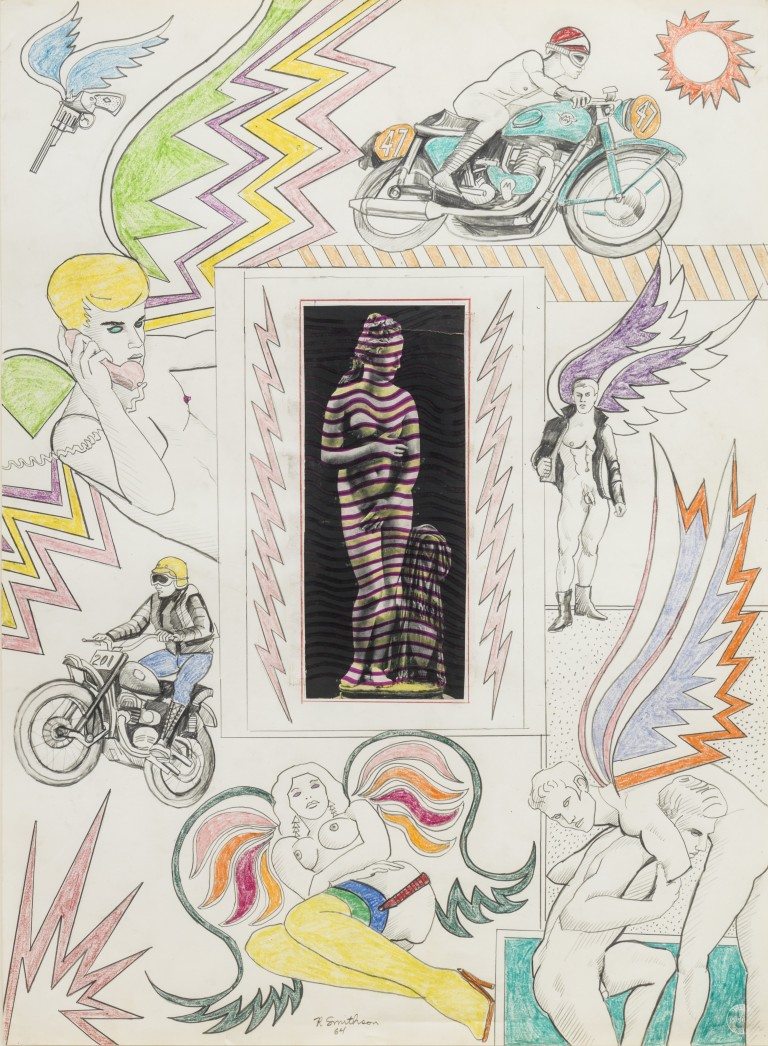

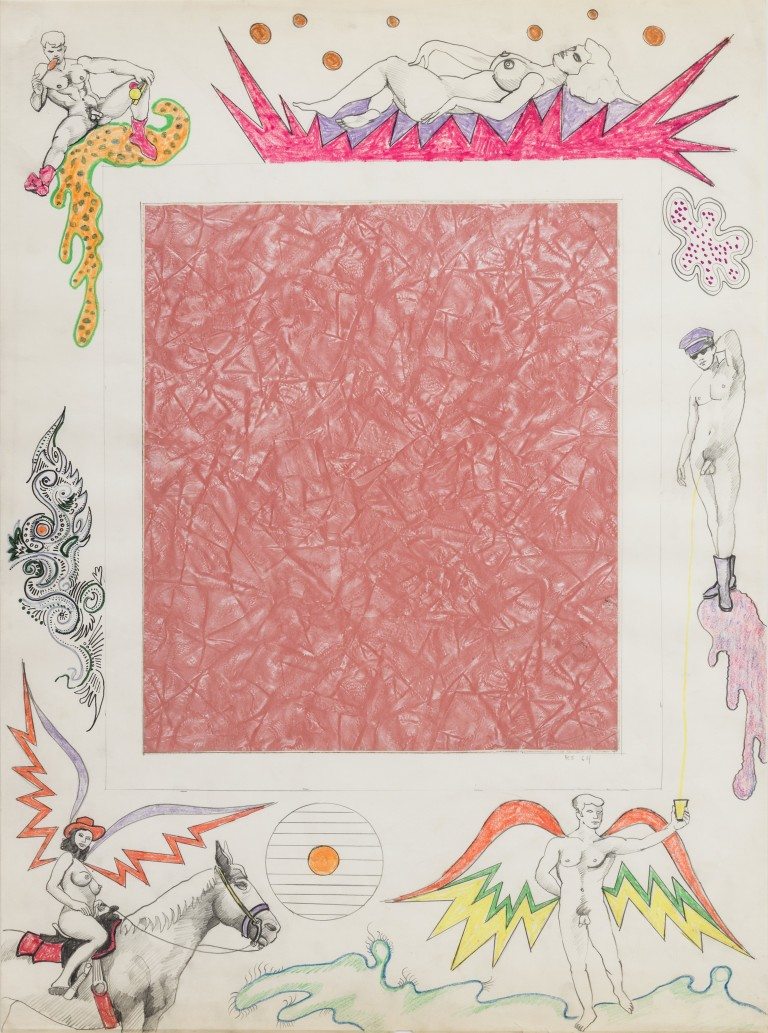

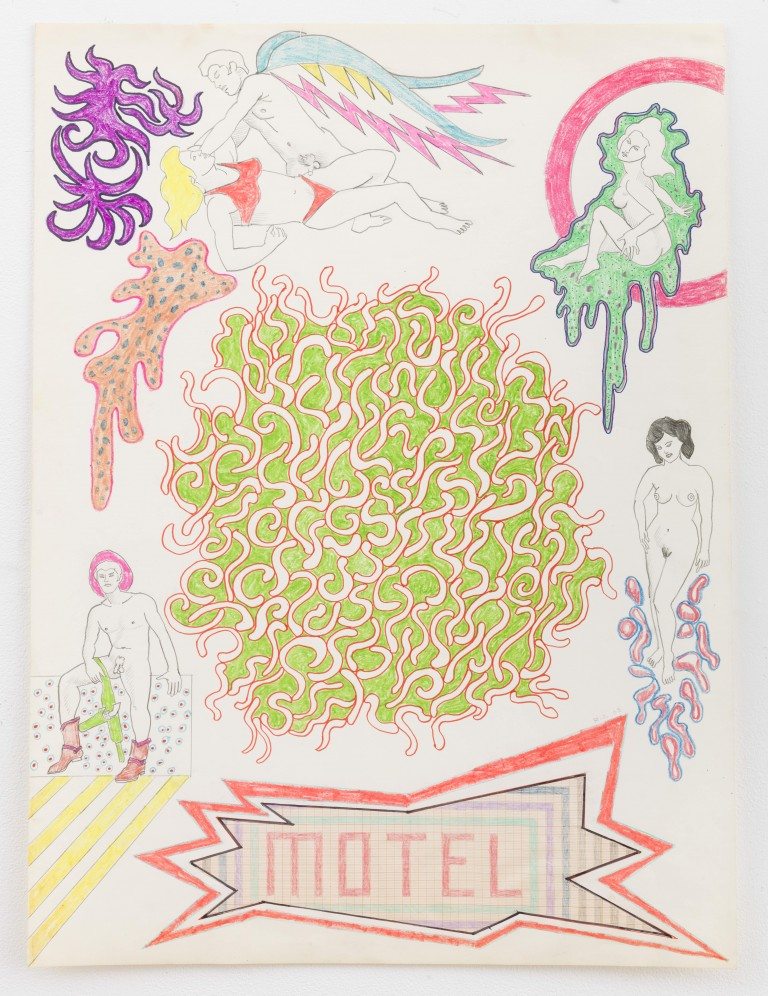

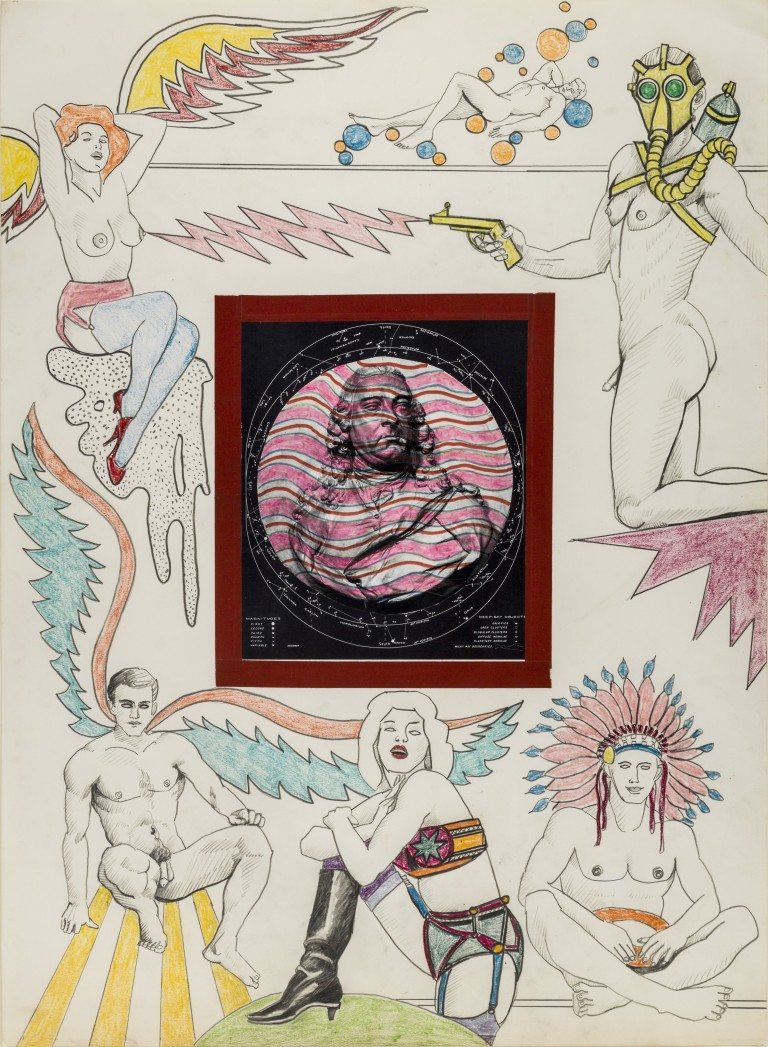

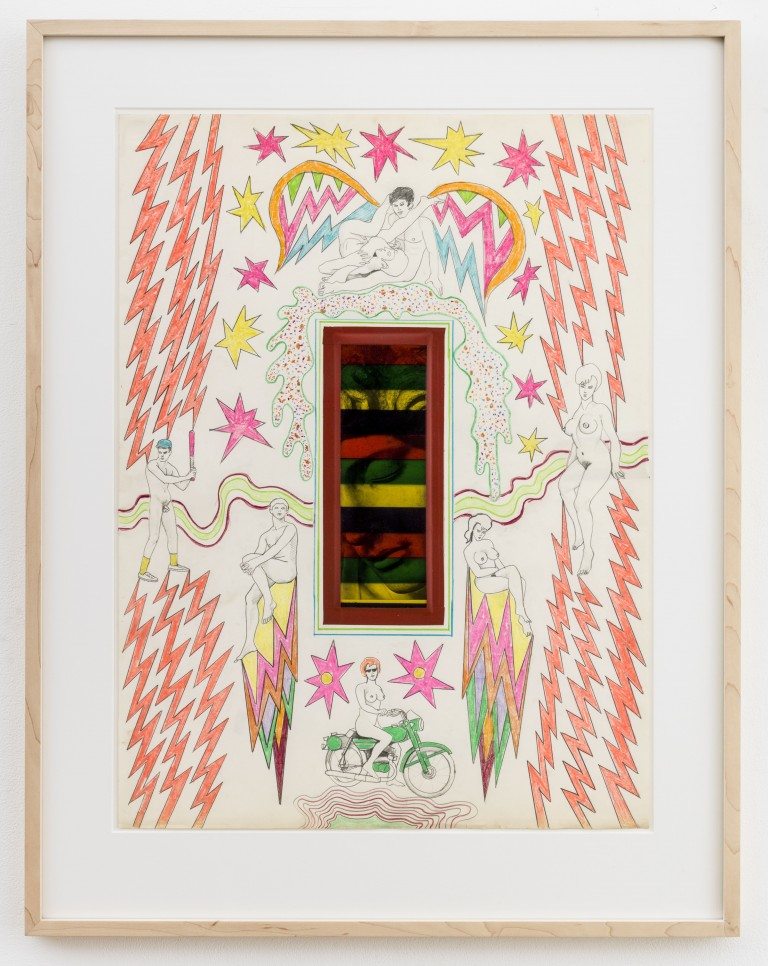

Smithson described his process as “digging through the histories,” starting with the landscape of sleazy magazines, mainstream culture, and the social scene directly surrounding him in New York City. In his early proto-psychedelic drawings, men and women – naked save for stockings, angel wings, and the occasional cowboy hat – pose seductively on motorbikes or in boxing rings in a pastiche of erotic comic book fantasies. Juxtaposed with religious symbolism, thunderbolts, dinosaurs, and Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, they are the spores of Smithson’s secret pop DNA. Filled with an assortment of these drawings, the catalogue features an interview with Paul Cummings recorded just a year before Smithson’s untimely death in 1972. It is a compelling first-person account of an artist in search of his voice, in which Smithson discusses ridding himself of the anthromorphism of his early drawings, before crystallizing his practice into the non-figurative work for which he is best known.

But more than forty years later, now that abstraction has become the lingua franca of good taste, these drawings make it feel unwise to lump Smithson into that category. His nude scuba divers and trippy cowgirls shine a blacklight on his coke-mirror-esque Non-Sites and the hallucinatory monumentality of Spiral Jetty. Like the psychedelic movement itself, Smithson’s work seems defined by an inextricable combination of mysticism and vulgarity.