Is this the Real Workers’ Revolution? (Or Are We Just Horny?) A Salute to KARLHEINZ WEINBERGER

|Eva Kelley

“My real life began on Friday evening. And it ended every Monday morning,” Swiss-German photographer Karlheinz Weinberger remembered during his first major exhibition in 2000. For most of his life, the semi-professional photographer worked in the warehouse of the Siemens factory in Zurich’s Oerlikon district, up until his retirement in 1986. But on weekends, the confirmed bachelor documented Zurich’s margins, developing a devoted cult following through his published works in gay magazines under the pseudonym Jim. For Weinberger, Saturdays and Sundays were more than the institutionalized intervals allocated to relieve a salaryman’s stress—they were pockets of freedom and desire.

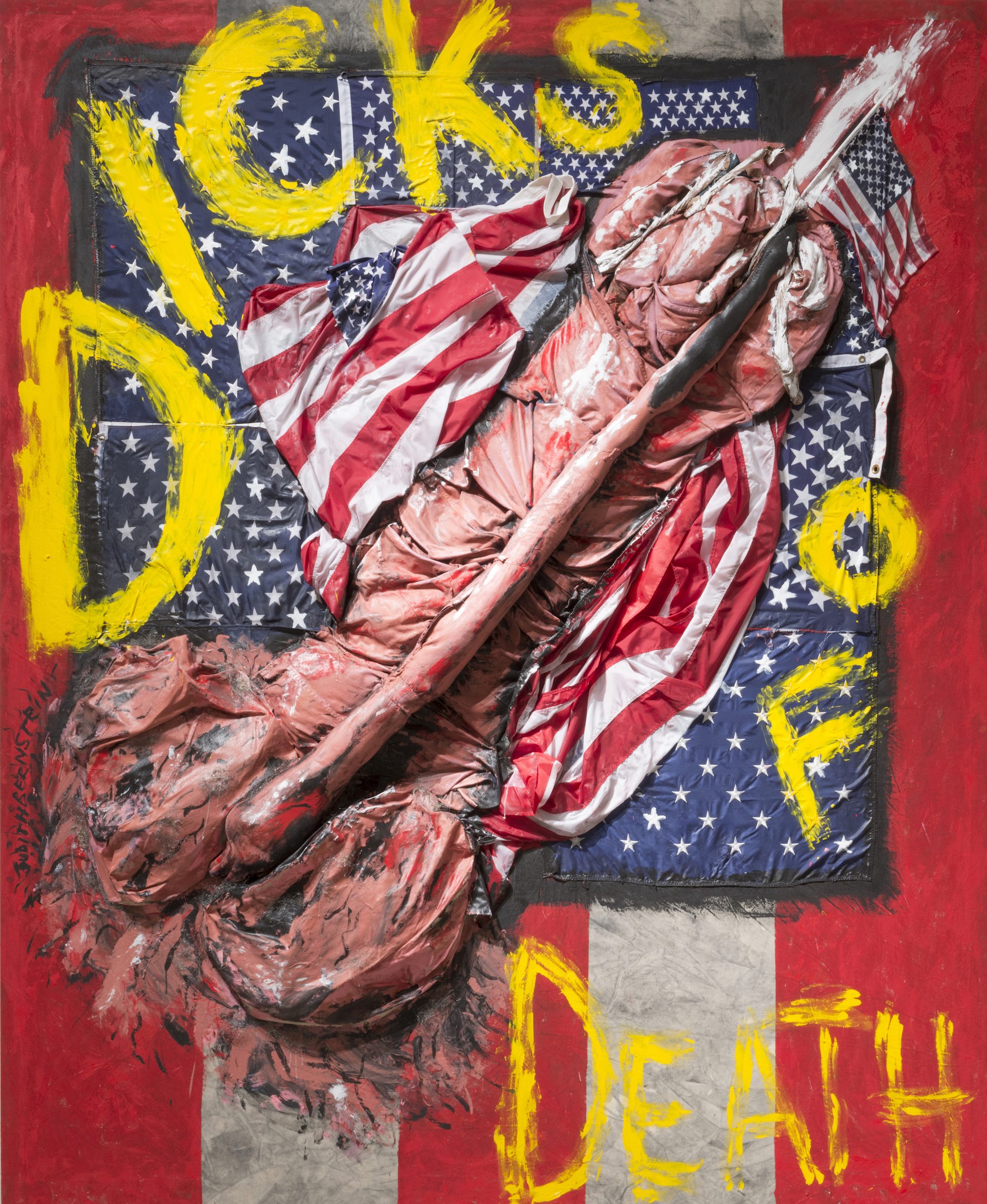

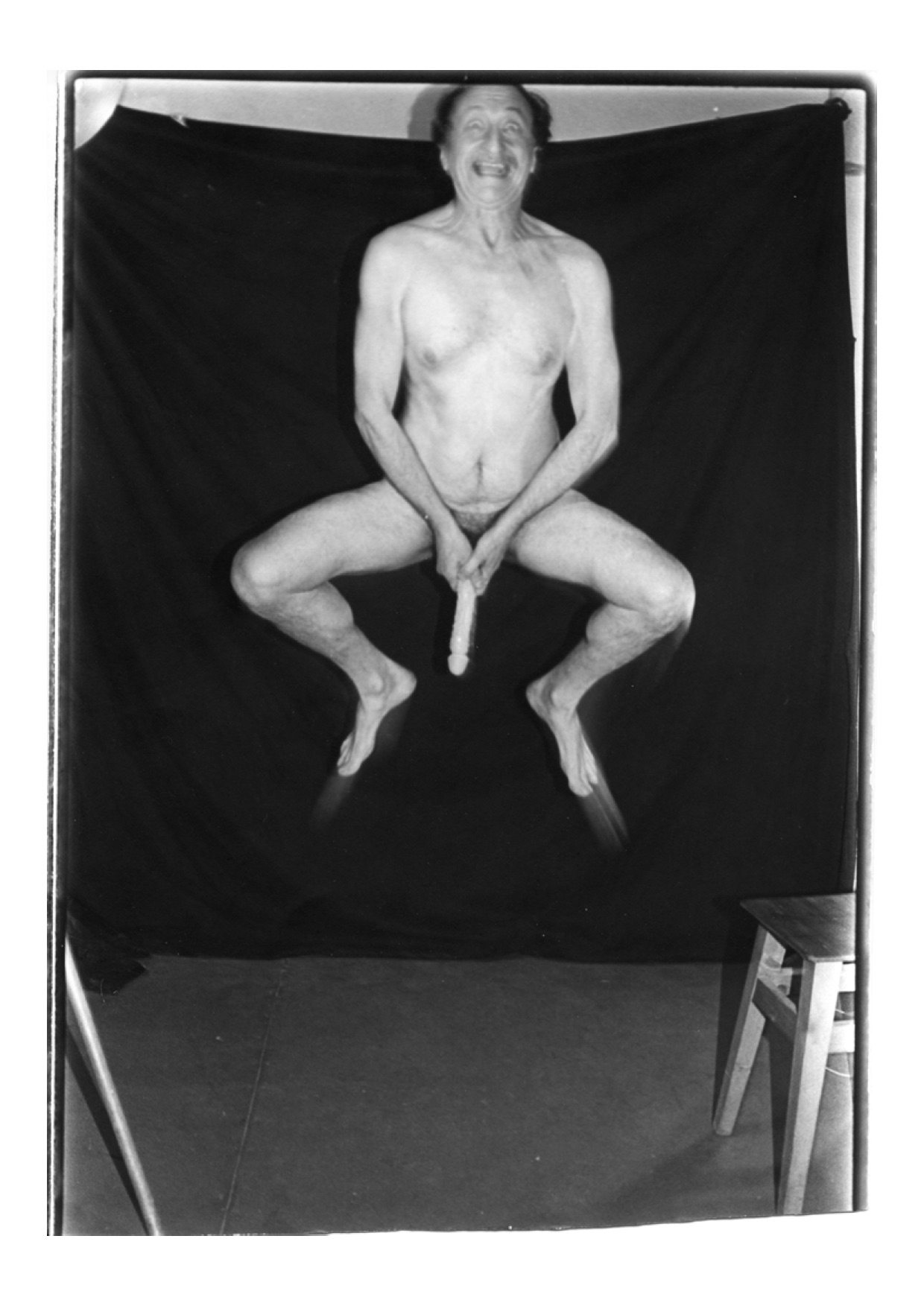

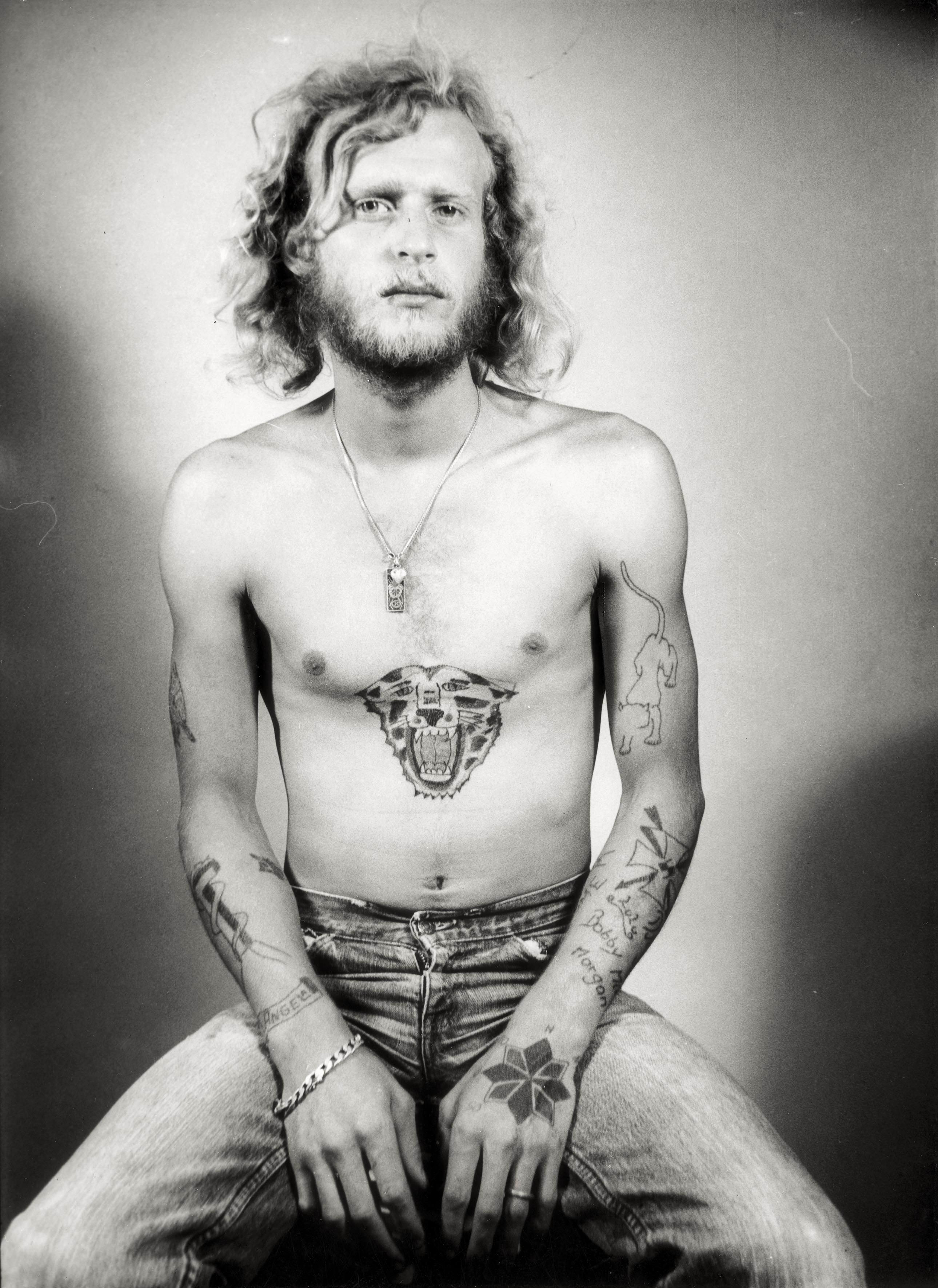

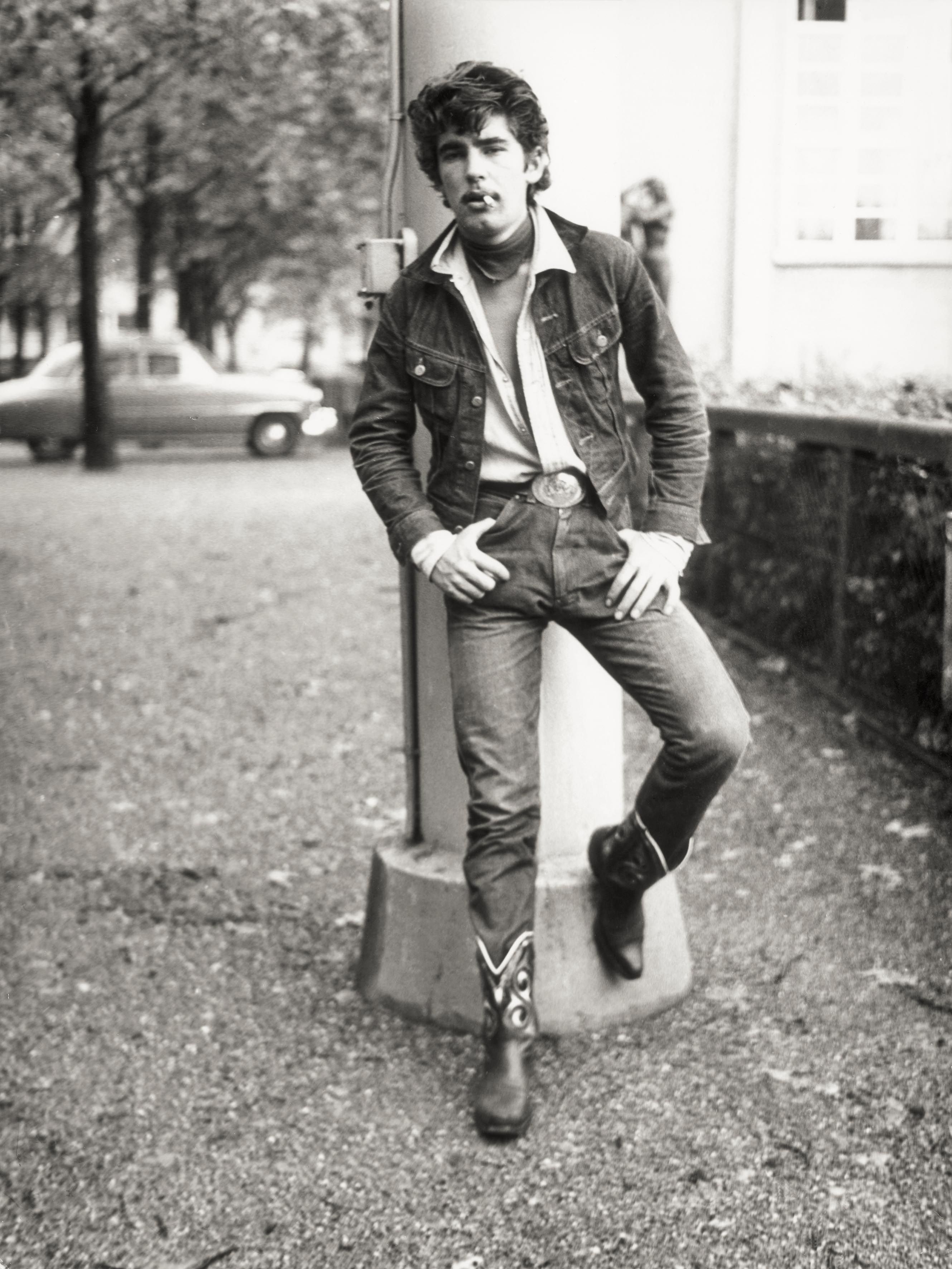

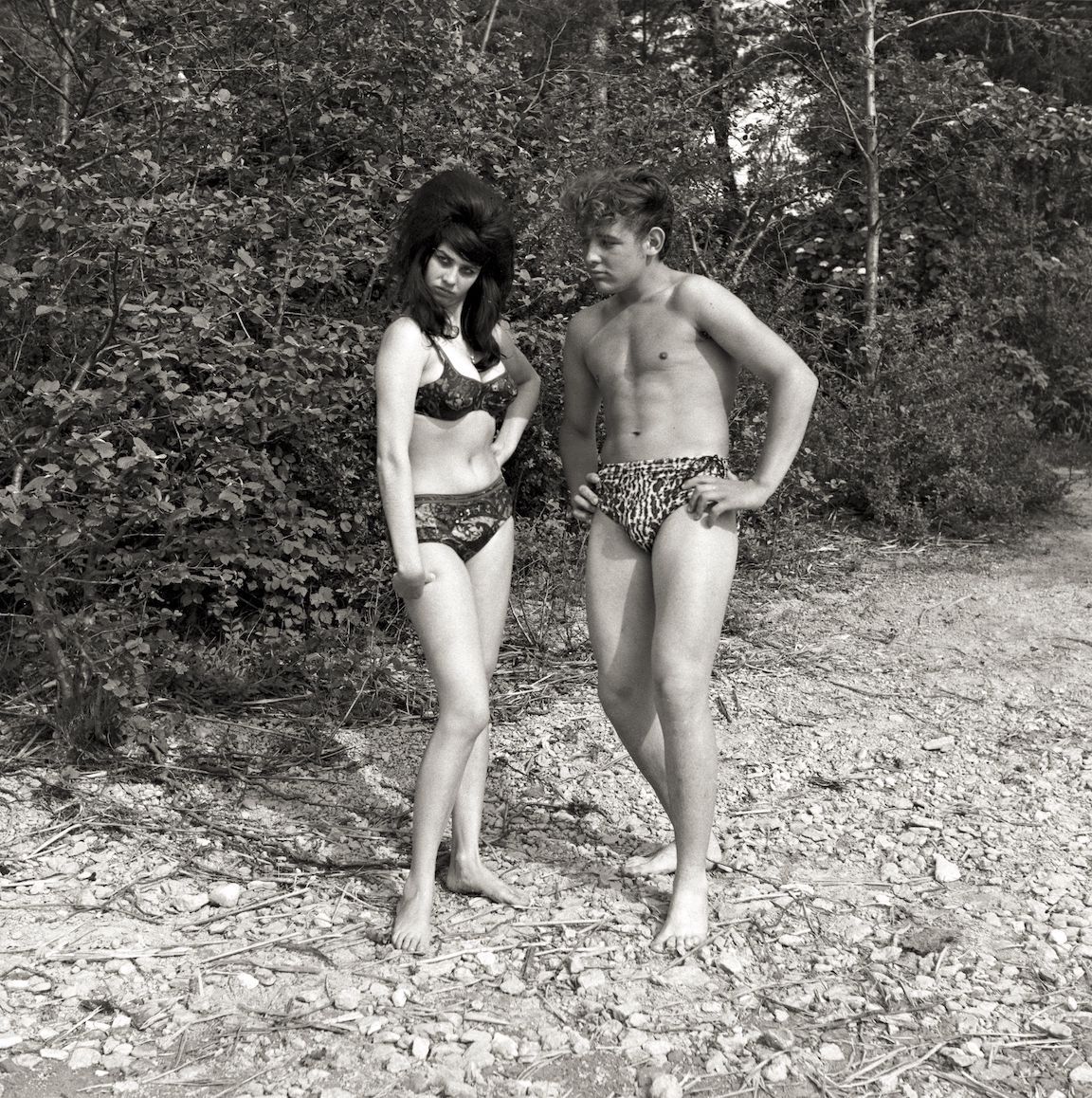

His posthumous book Swiss Rebels – an oxymoronically titled volume published by Steidl – catalogues Weinberger’s voyages into society’s alternate universe. They are studies of the mundane, the strange, the frightening. The fascination that Weinberger harbored for “the outsider” was validated through his own status as an outcast among them. Yet his camera mimicked a translucent barrier, keeping both sides safe. He photographed shirtless construction workers drilling tram tracks in the dusty road-sites that soaked up their sex-appeal. His Jeans series follows nubile and pock-marked teenagers through carnivals, galavanting in full-denim ensembles punctured with rusty nails and cinched by saucer-sized belt buckles bearing Elvis’s likeness. In Italy, he found bare chested Tuscans smoking cigarettes as they balanced contrapposto on Terracotta rooftops. Weinberger invited hustlers to his home to sit for him in weekly sessions, such as the homeless Alex, who spent afternoons at Weinberger’s watching television, drinking liquor, and masturbating for the camera.

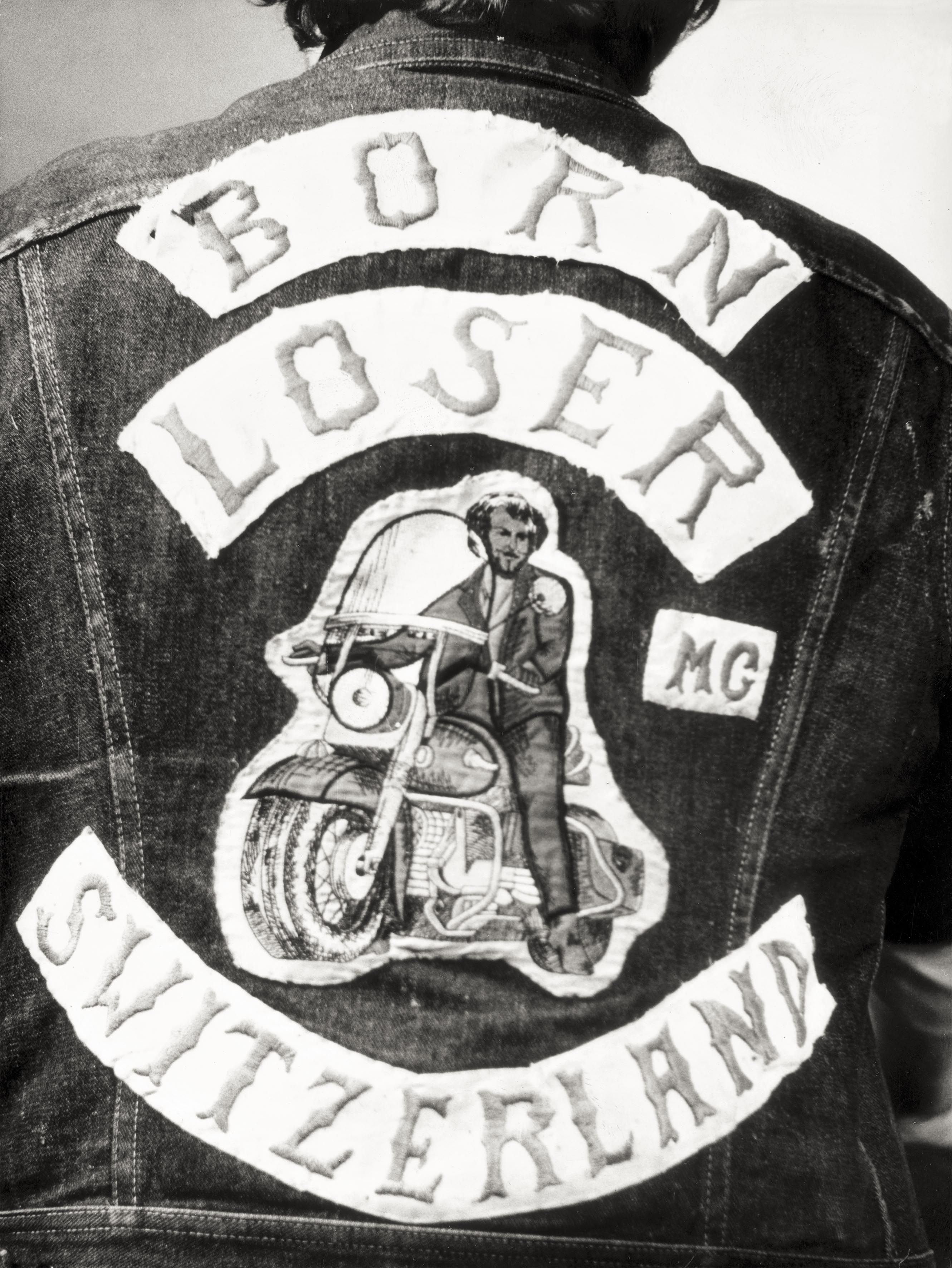

It is not until the section titled Elisabethenstraße that Weinberger closes in on the “Halbstarke” [Half-Strong], the German term for teenaged hooligans. Intent on subverting Swiss decorum, Weinberger’s adolescents stick horseshoes onto the crotch of their denim pants, comb their hair into messy bouffant dos, and dangle necklaces that either resemble the shell of a small canon or a medium-sized dildo. Some pose on stools in Weinberger’s makeshift studio, a sheet partition, while others deflect their gaze. But, as John Waters once said: “Who dresses like that and doesn’t want to be photographed?” As the Halbstarke evolve into adults, their style graduates into darker territory. The 50s teens mutate into bikers. Weinberger’s portrayals of Switzerland’s first Hells Angels chapter are of a tender and observant nature—a continuous trait in his work. The proximity of his lens vouches for this intimacy.

The monotony of Weinberger’s unfulfilled workweek may have been the catalyst that drove him toward his artistic expression. In this post-Jobs era where the “Do What You Love” mantra still echoes on, Weinberger’s blue collar Jekyll-and-Hyde routine seems almost seductive. Here, the tired nature of the work-life-balance is dismantled, and we realize that an exhilarating chasm can exist between what you do and what you love.

Karlheinz Weinberger: Swiss Rebels is published by Steidl (Göttingen, 2017). All images courtesy of Steidl.

Credits

- Text: Eva Kelley

- Photography: Karlheinz Weinberger