Body Performance: INEZ & VINOODH in Berlin

|Victoria Camblin

Helmut Newton is best known for the eroticism of his black and white fashion photography, for his work’s strong, sexy, and statuesque subjects, for his penchant for a bit of danger and a lot of leg. Less famous, however, are the photographs he took, over many years, for the programs and print materials of the Monte Carlo Ballet, capturing dancers on the streets of Monaco, around the city’s casinos, and indeed, nude in his own home. Rarely enlarged or included in presentations of his work, Newton’s Les Ballets de Monte Carlo forms the conceptual basis for “Body Performance,” an expansive new group show at the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin, curated by Matthias Harder.

The exhibition assembles imagery from major 20th century and contemporary artists – Vanessa Beecroft, Robert Longo, Viviane Sassen, Erwin Wurm, Cindy Sherman – to respond not only to themes of the human body, its documentation, and its movements in front of the camera, but to how the body inhabits the stage that emerges from any interaction between the photographer and the subject photographed.

Occupying an entire gallery within the foundation are works by Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin – billed simply as Inez & Vinoodh – a duo that has, as the exhibition materials put it, been “irritating the world of fashion since the 1990s,” pioneering the use of digital tools to manipulate and productively complicate the human form through their photography. The couple’s work inflames its viewers’ attention in the same way that an itch wanting to be scratched highlights otherwise neglected parts or sensations of the body. The images pose problems demanding – but eluding – solutions, and variously fuse masculine and feminine subjectivity, classicism and anarchism, commerce and critique, heroism and vulnerability, desire and confusion.

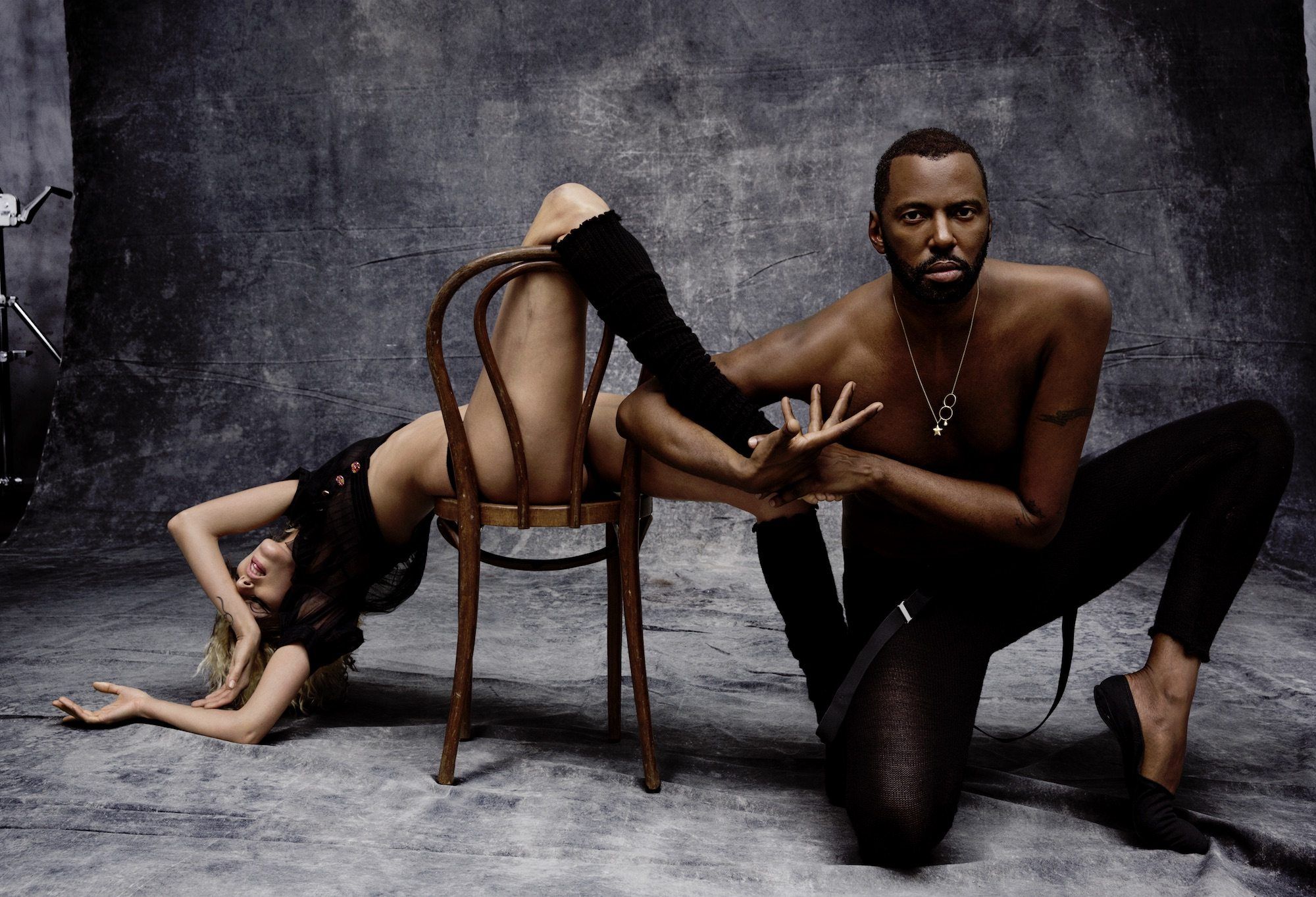

In addition to shooting models and celebrities, Inez & Vinoodh, like Newton, have a history of photographing stage performers: they’ve worked regularly with the Dutch theater company Mug Met De Gouden Tand, and shot Stephen Galloway and Anja Rubik for a 31-page cover editorial in 032c Issue #28 (Summer 2015). Responding to the topic proposed in Berlin, the photographers present a selection of work spanning several decades and genres, placing campaign imagery and editorial portraiture alongside experimental series in one exhibition space. That’s where they met 032c executive editor Victoria Camblin for a preview in the final hours of installation.

Victoria Camblin: The title of the show is “Body Performance.” The “body” part is kind of more overt in the discourse around photography and around your work – specifically, the body modification, the digital enhancement – but how does performance come into your practice? Both in terms of what you’re doing as photographers, and in terms who you’re photographing and how they’re performing for the camera?

IvL: I think at the basis of the photos we make, there’s always the body as a kind of extreme way of expressing how you’re feeling – in addition to how we think a person should be represented, or how the clothes would look their best, if we’re shooting fashion. So we play a lot with body language, even with aspects of dance in our work. We’re so influenced by what a hand gesture means, where the pose ends, all the way through to the fingertips. We’re not really the kind of people that go, “Oh yeah, just go stand there.” That never happens. Even though sometimes we wish we could be those people, we’re not. It always ends up being, “Okay, now arch a little bit more and then put your foot out more and stretch that arm more or swirl your neck up more.”

VM: It’s almost like a dance.

IvL: All together.

VM: And it’s almost like a still life in its preciseness.

IvL: So, it’s never spontaneous either. That’s the other thing. When we’re photographing people, we say to them, “We’ll direct you. We’ll coax you into holding your hands a certain way and to sitting a certain way and to moving a certain way.”

VM: It’s almost the same as how Helmut directed his subjects: move this; move a little in this direction.

So essentially, classic, ballet-level choreography? I mean, even though the images don’t look remotely historical – if anything, they’re futuristic – you can sense a kind of classicism in them. I always think of the vanitas of the Dutch Renaissance.

IvL: That’s definitely a big influence for us. Everyone always asks us, “What is the influence of Dutch art?” And it’s always there. There’s just a certain flatness in the Dutch paintings of the Golden Age that for us sort of comes naturally.

Those vanitas compositions are very death oriented – there’s always a skull or something morbid, and there is a darkness in your work, too. There’s a lot to say about sex in your work, but it also makes me think about death.

VM: It’s what we all do in the end!

IvL: It’s always there. I think when we were younger, there was much more of this idea of trying to – maybe almost defy death? And then trying to find ways to incorporate it into the work, even with our fascination with breath for example. And even now there’s always still some sort of darker undertone. But it shifts more now, just with experience and with growing up and making work for quite a while, you kind of don’t force yourself to put everything that’s ever gone into your head into one picture. In the old days I feel like we both had so many ideas and tried to put all of them into each image. We still sometimes say to each other, we have to calm down and distribute the wealth a little because we make so much work.

And the idea of the still life provides a consistent frame while you explore different ideas?

IvL: There’s always a frontal look. We’re not very three dimensional in our choosing of an angle. Actually, since Vinoodh and I shoot together, that has become kind of more interesting because my first intention is to be frontal, to be directly in front of the person that’s facing me. That’s it, my initial instinct. But while I’m being frontal, Vinoodh walks around with his camera and takes pictures from different angles, so it adds a three-dimensionality to it – another layer. For instance, the new image from the Louis Vuitton campaign for Virgil Abloh’s first men’s collection, it’s clear Vinoodh took it because he took it from a different angle, and that’s why there’s this depth in there. Let’s say in my version, that image is much flatter.

VM: But then sometimes we don’t know who has taken the picture.

IvL: That’s what’s exciting with working together. It offers up an approach to a subject from all angles, really.

There’s another art historical thread there – it’s basically a Cubist approach. It’s not a portrait of a thing, it’s a walk around the thing. Your work is two dimensional, but making it is completely embodied. And movement is more important as a part of the process than as a part of what’s conveyed in the result?

VM: And the question is always more important than the end result.

Would you say that about your commercial work as well, since that obviously has a specific end goal?

IvL: The fashion work has a clearer demand. The bag has to be visible, and you need to be able to see the buckle. So that’s what we do. That’s part of it and there’s no mystery.

VM: But some clients also make us feel free to do what we want to do. For the Vuitton campaign for example, we could do exactly what we want.

In general it seems like you’re not trying to make distinctions between perceived opposites. Art and commercial work, movement and stillness, life and death – we know they aren’t really separate, but we all still struggle with the duality.

IvL: It’s all dualistic in a way, and this tension is always in the work. But I hope it’s not spelled out like that. It’s more about this pull between beauty and something ugly, or something grotesque and something very glamorous. Everything being present together, all the time, is basically what it is about. In some works it’s much more obvious than in others. It can go from very extreme to very subtle, depending on the subject and where we are. Sometimes it can just be in the way an eye looks into the lens or how a finger is held.

It is not the body part that comes to mind when you think “Body Performance,” but fingers, or hands, seem to have a strong, troubling presence in this exhibition.

IvL: Hands are always important in our work. In the Thank You Thighmaster series, they’re very red, because we wanted to show a body that is full of blood. That there’s life in there, but it just can’t get out. There’s no way out. There’s no way to actually physically have contact with anyone. But the blood’s there. It’s streaming. It’s circulating. But she’s locked up. There’s this barrier.

VM: We made this work in the early 1990s, in the early days of the Internet and plastic surgery, and when people were starting to be obsessed with being perfect – with creating the perfect face, the perfect body.

IvL: But there was nowhere to go with it. It’s all about looking perfect, but there’s no true physicality anymore. We photographed mannequin dolls from the 1970s and then photographed the nude model in the studio and put the skin of the actual human over the doll’s face on computer. So it has this frozen emotion and this body that has no orifices anymore so that nothing can ever come out. Yet it’s perfect.

VM: It was a sort of prediction, and it’s basically happened now. On Instagram and everything else.

IvL: It’s about the idea of being so perfect that you are almost like this avatar that has another life. With the Cindy Sherman portrait, it’s pushing this perfection to the extreme, and into the future, almost. Like in ten years from now this might be totally normal makeup, although now it’s just what these face filters on Snapchat are doing, with the bunny ears and the mouse nose or whatever.

Not to sound like a shrink, but how does it make you feel to have kind of predicted this in your work to such a degree? Or rather, to have been working within that vocabulary for so many years and making a substantial amount of work with it and then seeing it become so mainstream?

IvL: In one way, it makes me think how little really has changed, in fact. Of course, much more is being discussed right now compared to the 1990s. People were quite shocked by the Thank You Thighmaster series. It could only exist in the art world, whereas now –

VM: This is reality.

IvL: It’s happening in real time, and it’s much more out in the open. Whether it’s fully worked out or assimilated, I’m not sure, but I do think everything’s on the surface now. And I’m kind of excited for that reason, too – excited to show this in a museum today and see that it’s just the same as it was then, the same discussion only much more common. And it’s exciting to see that over time there is this body of work and that the images that start to exist on their own – even if they come from series, they live on by themselves.

VM: And they become timeless – you can’t define time between them.

I love that you said that things are the same. People love to pronounce things “over” or “dead”: this medium is dead, and it’s been replaced by this one. We are so quick to try to end an era or generation and begin a new one that we don’t see how consistent our conversations and obsessions are.

VM: It’s also time for us to realize that we can exhale. We don’t have to be on Instagram constantly. We don’t have to post on Facebook every day. We can go back to the basics and start playing again, and step away. With print, there are different ways of making a magazine. It doesn’t have to be always the same. It’s actually very exciting if you think about it. It’s freedom. It’s awesome, and people should realize they can also have that freedom.

IvL: I agree. I feel like the freedom they have now is much bigger because of it all. When people say, “Magazines are dead,” I’m thinking, “No.” Because you can do anything you want now, because there are no rules anymore because it doesn’t matter.

The function is different.

IvL: Completely different. Now you can just go right ahead and change everything you have constantly if you feel like it, because it’s all open. I find that fabulous. It’s a very exciting time, a time of no rules. Everything is sort of leveled, so there’s just a lot of possibility for sticking your head out.

But that freedom makes a lot of people very afraid. It’s like a vertigo almost, isn’t it?

IvL: Yes. And I think it’s because they’re maybe not flexible enough in their minds to find other streams of income.

VM: You have to adapt, you have to find a creative solution for it, and just use your brain.

IvL: It does take time, and it takes courage, I think, for a lot of brands and a lot of magazines. So you have to be courageous at the moment and really, really try to bend it all to your own terms. A lot of people say things like, “Oh, aren’t you scared? Because everyone’s a photographer now.” But we’re like, “No, it’s good.”

VM: You know, it’s not like everybody is a writer just because of Twitter, either.

Trust me, I’ve had to tell myself that.

IvL: I mean to me, the more imagery that’s out there, the better. It’s great because people are actually seeing now. Visual language is bigger than ever before.

In terms of everyone being a photographer, how concerned are you with professionalism, with expertise acquired over time? Your work is very intuitive, but it has a framework of precision, of mastered skill within a medium.

IvL: It is very intuitive, but you draw from this vast amount of experience and also from your whole archive of imagery that you’ve made before. You bring all that with you to any situation, and then try to invent something new every time. In the fashion industry, we’re being paid to make imagery that sell the clothes or the bag. Even with the image from the Vuitton campaign, where there is no bag to be seen, no clothes, it’s there to make people wonder about the clothes and where they come from. In that context, we know we’re hired for that, and we make sure we deliver.

VM: Also, we’ve worked for 30 years with the same lighting director, which takes away a lot of stress for us. So we can just be free at that moment, during those 20 minutes, while he works the whole day how to figure out the lighting.

That’s different than, say, a young photographer needing a lighting director because they got huge before they had time to learn how to do it.

IvL: That’s the thing. First you have to know how to do it all. A lot of people ask us like, “Oh, what do you say to young photographers?”

VM: First: stay in school. And second: it takes ten years to have your own vocabulary.

IvL: It takes a long time. But now, especially because of Instagram, young photographers are pushed to do too much too soon, and it’s not healthy. We sometimes have to take 18 images a day, plus a video, plus a BTS, plus an Instagram story, plus whatever. And we can do it, because we have the expertise and experience, but you can’t really ask that of someone who’s just starting, who doesn’t have a whole reservoir of experience or imagery that they’ve made already to draw from. And I think that’s where a lot of them sort of fall through the cracks.

Maybe that’s where the anxiety around it comes from, the question of whether or not these careers are sustainable.

VM: Also, we don’t have a union.

IvL: We don’t have any rules now. And it keeps evolving. But we keep trying to educate our clients to say like, “Look, you don’t need that much content. You don’t need to post 20 images a day.” You know, you really don’t. But it’s a work in progress.

VM: For a half a year now, we are working with an AI specialist, and he tells us how his data going back to 2015 shows that you don’t need so many new images every day. You don’t need them. But people do like unexpected new things. You had better have one new image and repeat it, perfect it, than 500 entirely different things.

IvL: Things that have nothing to do with your brand kind of dilute your message. It’s purely volume based. It makes no sense actually. It actually confuses people. You might as well just put a tile on Instagram with just your logo on it. It would be better than a crappy picture of a shoe that doesn’t belong to the world of images that you’re creating for your brand. It takes courage for brands to understand and to leave that model that they’ve now forced themselves to adapt to over the last few years.

Individuals, meanwhile, are becoming more adaptive, more fluid. Gender identity is one example, which of course you have long questioned in your work alongside other forms of fluidity.

VM: For The Forest series, we photographed men in quite passive or stereotypically “female” poses, then replaced their hands with the hands of a woman. We set out to photograph stereotypical masculine guys, so we went to a casting agent and were like, “Okay, show us the most average guys you have.” One works at the gas station, another at the hardware store.

IvL: The idea was to talk about how masculinity is represented in art, or rather how it’s not represented in art very much. Maybe an artist would photograph or paint himself, but only rarely. I mean there are idealized versions of the perfect male, from way back when, but I think there’s very few people that actually talk about masculinity. So we said, “Let’s try to bring that to the surface. We all have a male and female side inside us, so let’s try to destroy this idea of what is masculine and what is feminine and sort of blend it all into one.” That’s what we did here.

VM: Also, hands are weapons.

IvL: A hand could hit you. A hand could kill you.

VM: And a hand could stroke you.

Or communicate something very sophisticated. In addition to the idea of dissolving the binaries of male/female, etc., it seems like your work is about the dissolution of this idea of the self as a coherent whole. I’m thinking of all the discourse about selfhood happening right now – about “self care,” self-actualization, self-definition when it comes to identity, even if it’s non-binary. It sounds like we’re not just talking about blurring lines between perceived opposites, but blurring the contours of individuals, too. Even in the way you guys work together, in how you sometimes don’t even know who took a picture – maybe even as individuals, we’re not as solid as we think or strive to be?

IvL: Historically, culturally, we’re so programmed to see the male as the dominant figure, and it’s hard work to see male and female as equal still. What is the image of equality? And how do you even eroticize equality? It’s really difficult. In the way we work together, as a man and a woman, and the way we are affected, we don’t see those separations. We just see ourselves as two brains that make work. I always think that we’re sort of an example of how it can be it if you abandon that whole idea of difference. I mean we’re kind of defining it.

VM: People are always like, “Is it difficult to be 24 hours together? It must be very tough.” And we’re like, “It must be so strange to have different jobs then go home, spend three hours together, go to bed, and the next day you’re gone again.”

I wasn’t going to be one of those people who ask you about your 24/7 partnership – but people fetishize it, right? That’s what they want to talk about, because they imagine this intensity and intimacy.

IvL: You know, it’s fascinating. Again, it’s about seeing each other as separate – and we really don’t.

But this dissolution of the individual, it’s not just in your partnership – it’s visible in your portraits. If you’re taking a celebrity portrait, it seems you also poke holes in their idea of their own persona, or in the public’s idea of the celebrity. It’s quite mischievous.

IvL: We try to. But in a way that still makes them come out like a hero. I think for us the big thing is showing the heroic side of a human is important. And it could very well be that Helmut Newton is the one that taught us that. There is something about showing someone’s power without it having to be a display of power. But in the way a person is photographed, what is very important to us is just bringing visually everyone up to that level – and not just a Brad Pitt, but literally everyone.

The heroism in your work seems to be located in vulnerability, though.

VM: Because everybody has that.

IvL: Yeah. And we are attracted to the openness of that. Someone comes in and you have literally five minutes to establish trust and then you have twenty minutes to take the picture.

VM: If you don’t have that trust, you will never get it. You have to be totally open to the other person.

What you’re describing sounds like an erotic encounter. The vulnerability and the fear, and the surrender required to get through that.

IvL: It is like that. It’s this kind of conquest, you know? It’s confrontational. And that’s definitely the addictive part of what we are doing: that exchange of trust and letting go of your own ego and then what comes back through the lens.

VM: Most of the time, what comes back is self-portraiture.

IvL: What’s exciting to us is that over time there is this body of work with all those images that have sort of come to the surface and start to exist on their own – even if they come from series, they live on by themselves.

VM: And they become timeless – you can’t define time between them.

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin