Made in Heaven: Gerrit Jacob

|MAX ROSSI

Balancing kitsch and new-wave chic, Gerrit Jacob has established himself in less than two years as one of the few promising talents in Germany’s fashion scene.

For the London-educated, Rome-honed designer, and Berlin-based founder of his eponymous label, “everything needs to reflect real life.” If life feels at times wild and erratic, so too do Jacob’s collections—madcap ensembles that combine elements like flocking (a technique typically found in car interiors) with Japanese satin and pearl details.

The designs collide rave energy, biker grit, and workwear utility in oversized polychromatic pieces that burst with vibrancy and airbrushed finishes. As a result, the wearer is morphed into an anime-like character, which is no coincidence since Jacob cites Japanese illustrator Satoshi Kon as one of his key aesthetic influences. Yet beneath their playful, hyper-stylized surface, these collections grapple with bleak cultural undercurrents. SS-23 Raised by Wolves, for instance, was inspired by Jim Goldberg’s visual account of homelessness and served as Jacob’s personal vehicle for social and class commentary.

For his recent collaboration with MUBI—a global streaming platform, production company, and film distributor dedicated to elevating great cinema—on Reclaiming Spaces: Berlin, the ’90s, a series exploring the capital post-reunification, Jacob created a limited-edition capsule channeling the era's spirit. The five pieces, including a graffiti-scribbled denim jacket, display his nostalgic point of view. To mark the occasion, Max Rossi spoke to Jacob about building a lasting foundation, the intersection of arthouse streaming and fashion, and club nights as therapy.

MAX ROSSI: In previous interviews, you’ve mentioned that your focus has been on building a foundation. Could you describe what that foundation is?

GERRIT JACOB: I used to work for Gucci, and they have these iconic codes of the house, some of which are over 100 years old. They can tap into these codes and reinterpret them each season to tell new stories. I really felt that, when you’re starting out, you don’t have that privilege––I have my foundation as a person, but it’s not established in the world yet. So, for me, it’s been about building that base, crafting the brand and what it’s about, and establishing visual codes––the codes of storytelling. It’s not necessarily a process where, at the beginning of every season or project, I sit down and ask myself, “What are the codes? What am I going to do?” It comes naturally to me, and it always circles back to oversized shapes, leather, strong color palettes, coming of age, memories, and nostalgia. These are the elements that always speak to me and that I instinctively gravitate toward every time.

MR: Your past work features visual motifs that are quite particular to you, especially airbrush patterns. What other techniques do you use and how do they come about?

GJ: They're kind of woven out of storytelling and texture. I love using flocking—it’s often found on car parts, tacky restaurant walls, and little figurines. I’m drawn to anything satin, anything dazzling—I feel like a magpie, captivated by shiny things. There’s just something about them; I can’t quite describe it... it feels expensive and appealing. I also like to juxtapose busy, intricate patterns with something quieter, something that feels luxurious and romantic to me. Each season, I focus mainly on one or two elements. For example, last season (FW-24: Made In Heaven), it was a checkerboard print—something that evokes competition and ties everything together.

MR: Some of your choices might seem a chaotic at first, as you combine elements that don’t typically go together—you pair airbrush with Japanese satin, and even pearl buttons. How do you harness this chaos?

GR: The way I see it, I want the work to feel authentic—I want it to feel real. It’s quite personal. And, you know, life is messy. Life is random. So it would feel weird if the work weren’t a little messy and random too. As long as it feels right, as long as it feels like it belongs, then it’s going to work. For me, cohesion is intuitive. That’s my approach to everything. That’s why I’m drawn to harsher elements, but I also love pearl buttons. I love bringing a sense of romanticism into it, even within the prints themselves. Not everyone agrees with this, but it’s my version of elegance.

MR: And this thought process is encapsulated in your recent collaboration with MUBI. What drew you, as a fashion designer, to collaborate with a streaming platform?

GJ: It all started when they asked me to take part in a panel talk for High & Low—John Galliano in April 2024, and it was also a collaboration with Vogue. Then, we came together again for their Berlin film series (Reclaiming Spaces: Berlin, the 90s), launched in collaboration with the exhibition at C/O. It was initially meant to be some merch, honestly—like a t-shirt and some tote bags. But it quickly grew into more pieces, a campaign, and a whole story that speaks to the rebellious spirit of Berlin in the 90s. The more I spoke with their team, the more a fashion collaboration made sense, because, as a streaming platform focused on arthouse and independent films, their ethos is about platforming artists. Everyone has been really open and encouraging, and there were very few red lines, which is quite rare. Normally, they want you to push a big product in fashion collaborations and just create a version of it—but that wasn’t the case here at all. I had complete freedom, which was amazing.

MR: Growing up, were you watching a lot of movies? Did they shape your sense of aesthetics?

GJ: 100%. I feel that cinema is a big part of visual and pop culture and collaborating with someone who has such a strong point of view in it was really cool. As a child, I used to love Disney’s Hercules (1997), and it’s probably still my most-watched movie ever. I know that MUBI is supposed to be more highbrow, but I think Hercules was the first movie I truly loved. Out of all the Disney movies, it’s also the most stylistically unique for me, as it has this distinct style of drawing by cartoonist Gerald Scarfe.

I also love anime, especially Satoshi Kon, which I think is reflected in the collections. As I mentioned earlier, I loved coming-of-age movies as a teenager, and I’m still obsessed with them today. I adore all of them. My favorite is probably Dazed and Confused (1993)—to me, that’s the most iconic coming-of-age movie of the 90s.

MR: The exhibition and collection are an ode to Berlin in the 90s, but Berlin is also where you’re based now. Why did you choose to settle here?

GJ: I didn’t live in Germany for 10 years, and especially after Italy, I felt like an alien in the South. I was just longing for home—for kebabs, Apfelschorle, and that kind of stuff. I used to come to Berlin every summer to party, quite frankly, and I was always looking for a way to move here. But back then, there weren’t many fashion jobs. After Italy, it was a choice between London and Berlin, and I had already been in London for eight years—quite a long time. Berlin felt like this new shiny toy, and I wanted it.

MR: Perhaps you foresaw that this city could offer you something London couldn’t?

GJ: One of the big differences between London and Berlin, for me, is that Berlin is much quieter. It’s a vast city with a lot of open space. In London, the emerging fashion scene feels like a shark tank. It’s not the ideal environment for creativity—a shark tank. Here, it’s much more inspiring, and when you want to go crazy, you can. The nightlife here, at least for me, is more enjoyable.

MR: Is club culture an influence?

GJ: For sure. I feel that nightlife is always a community space for queer people, and that’s true here as well as in London. I used to go out a little too much, especially in my early 20s. When you’re 18, 19, or 20, you’re confronted with all these different types of people, and you get to experience everyone. It was quite magical. Even today, it’s quite intense to run a brand and be self-employed on a daily basis. The highs are very high, and the lows are very low. So those moments when you go to a great set, you’re intoxicated, dancing—it's one of the few times I can truly let go. That’s quite special to me, and precious.

MR: It’s a moment to disconnect.

GJ: Yes. One of the very few.

MR: The collection shares your sense of nostalgia. It’s a warm representation of the '90s as a golden era. Suddenly, the wall came down, and there were all these new spaces where people were mingling, partying, and creating. Do you think that’s something we’re missing now, both in terms of culture and fashion?

GJ: I love nostalgia as a tool, and I feel like it’s obviously a falsified, idealized version of the past. It’s also just fun to play with creatively because everyone is nostalgic for certain times in their life. Everyone looks back and thinks, “Oh my god, remember when I was there, when I was younger, when I was doing this?”

From a fashion standpoint, I was looking at an issue of Collezioni magazine, which featured the fashion collections from Spring and Fall 99, and it’s just classic collection after classic collection. These are iconic product collections—like McQueen and Helmut Lang—and all these names spawned from that period of seven or eight years that are still highly influential today. But times change, things are different, and I think they’re ultimately always better. It’s just part of life that everything changes.

MR: The pieces you create are heavily influenced by your obsession with “coming of age” and “youth.” Why is this theme so important to you?

GJ: That's a good question. I think my theory is, and I’ve obviously thought and talked a lot about this, that when you’re in this period of finding yourself and coming of age, life is quite complicated. And for queer people, myself included, it’s even more so. There's a sense that maybe that time didn’t belong to you, and that’s a big part of where that obsession comes from. I always try to make sure it’s never too sexual, because it’s more of a serious investigation into that lost time, rather than just sexualizing it.

MR: At the same time, your collections often deal with dark social commentary. I’m thinking especially of Raised by Wolves (SS-2023), inspired by Jim Goldberg’s documentation of homelessness, or SCUM (FW-2023), inspired by queer aggression. Is your rave-like, whimsical vibe a Trojan horse for reflecting on deeper issues that aren’t as colorful?

GJ: As I was saying earlier, for me, everything needs to reflect real life. As an engaged person, those themes are always going to find their way into my work. At the end of the day, it’s going to be about trousers, a hoodie, or a jacket—things that already exist and have existed. So, it’s important to fit as much meaning and personal context into them as possible, for them to even have a point in existing. I’m not a writer, and I don’t want to comment on the issues of the day through writing, as it’s not my medium. But I do feel that I express it through the collections and the clothes. It’s not about being reactionary. It’s mostly about reflecting on the world we live in, which is constantly changing, and I feel it would be disingenuous for that to not be part of the process.

Part of Gerrit Jacob and MUBI’s collaboration was a panel talk at

C/O Berlin titled “Berlin in the 90s - Reflecting on the Past and Its Present Influences,” hosted by 032c on November 16, 2024.

Moderated by 032c’s managing editor Claire Koron Elat, the talk featured Gerrit Jacob, casting director Affa Osman, and photographer Christian Werner. The evening also marked the official launch of Jacob’s limited-edition capsule collection.

Dedicated Feature

Credits

- Text: MAX ROSSI

Related Content

Kiko Kostadinov: Hunting and Being Hunted

Marc Kalman’s Definition of Boyish

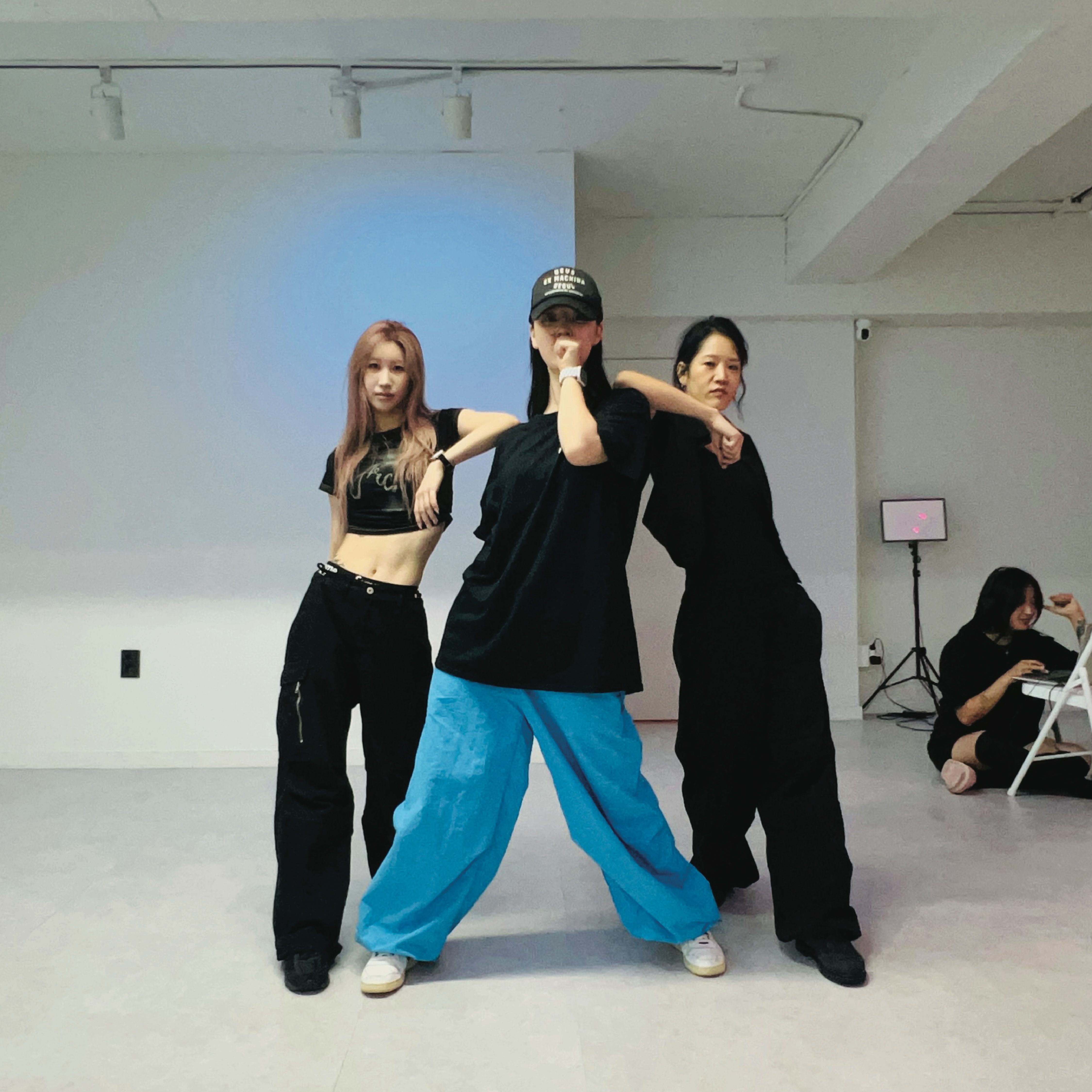

032c x aespa Capsule

SAAY: What is the distinction between life and art?

Moncler and Rick Owens Craft Personal Sanctuaries

Petra Collins Says Sorry

Where in the world is Paris Texas?

Aus Taylor: If I Died Tomorrow, I Would Be Satisfied

The Erotics of the Nerd

Who the fuck is Vaquera?

Officecore with Gucci

Brenda’s Business with GmbH