“More Atmosphere!” BRITTA THIE Paints Life on Set

|Cassidy George

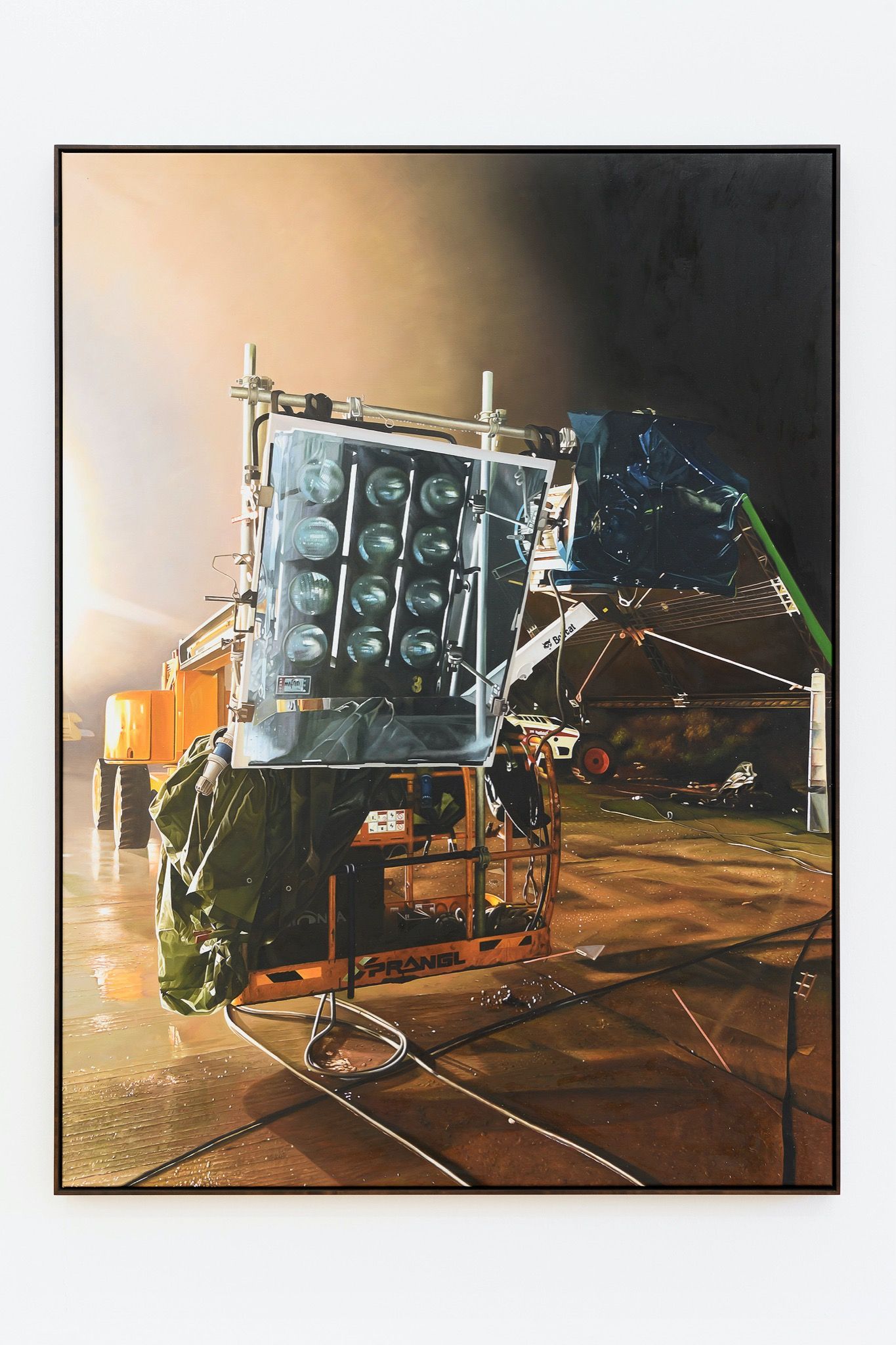

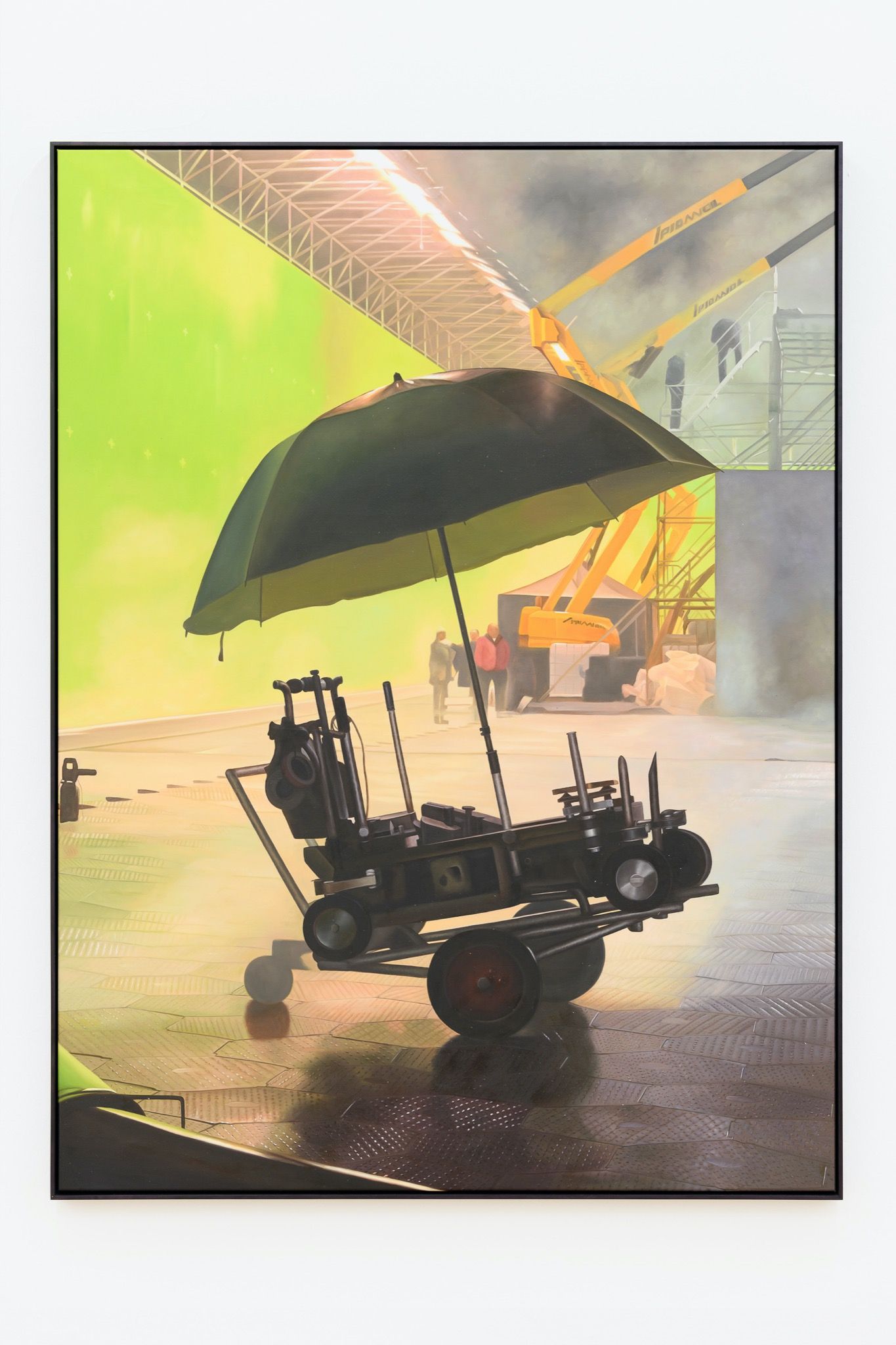

Film sets are portals to alternative societies, where the constitution is rewritten daily in the form of a call sheet, but professional hierarchies are fixed. Extras and talent coexist with prop masters and scene dressers in luxury trailer lots as ADs quarrel with 2nd DPs behind sound stages – all participating in a process that looks nothing like its end result. In this manic time-constrained ecosystem, where “booms” are soft and “hot bricks” are cold, the business of creating illusions is facilitated by analogue equipment and digital technology. This loyal, “crucially invisible” hardware stars in Britta Thie’s show “More Atmosphere!,” which is on view at Fragile until October 31

As a filmmaker, actress, and model, the Berlin based artist has found herself on many film sets throughout her life. Performance, Thie says, has always been an integral component of her artistic investigations – which examine the impact of emerging technologies and explore the liminal space between the dissolving binaries of man vs. media and self vs. digital. Thie is best known for video work such as Translantics, a digital series she wrote, directed, and starred in. With “More Atmosphere!,” Thie complicates her exploration of film by representing its workings, perhaps counter-intuitively, through paintings. The hyper-realistic – yet somehow not believable – renderings bring the contemplative stillness of a “slow” figurative medium to the ever-accelerating domain of big-budget media. What Thie’s paintings represent, but do not portray, is the contradiction of a system we all relate to as consumers – and the flux in our relationship to the devices we use as creators, in the production of ourselves.

CASSIDY GEORGE: After focusing on other mediums for so many years, did your return to painting feel like a homecoming? Or a new beginning?

BRITTA THIE: It felt like both, in a way. I’m known mostly as a filmmaker and video artist, so it might feel like a big twist – but I studied painting my whole life, especially as a kid and later, in my early art school years. Painting also made the most sense conceptually. I wanted to create tension by using this slow, analogue medium to portray a very fast one – the hyper mobile, streamed, moving image. I looked at the making of a high budget television show as a way to capture the transportation of its hyper polished images as data through our accelerating internet in still-lives, almost like a film close up. The idea was to create paintings of the objects that produce the high-resolution visuals we expect of contemporary TV – paintings that look as HD as the imagery we consume through our screens.

You’re clearly no stranger to sets, but why did you choose to paint this one? What was unique about its atmosphere?

I kind of slipped into acting through my own artistic practice, because I’ve always worked with performance within my filmmaking processes. I also used to model and did some commercials when I was younger, so I’ve found myself living on sets for years, on and off. The images I painted in “More Atmosphere!” were taken in a backlot in Budapest – a weird, artificial studio environment where major production cycles are constantly happening. It’s actually where they shot big parts of Blade Runner. We were only shooting at night, so I didn’t see daylight for the six weeks that I was living there. I was barely sleeping and working really long hours, so things got weird. After a while, I got so delirious that I started to kind of merge with all of this technology. I mean, I was literally talking to tennis balls!

In CGI, everything is added later, so you’re often interacting with characters that aren’t human and worlds imagined through a plain, impassive green screen. In one scene, I was acting with tennis balls stuck on a tripod – after repeating the scene many times, I even developed feelings for the thing. The tech-objects that create the atmospheric lighting conditions for a shot often perfectly light one another as well, dipping each other into the limelight off-camera. It’s a beautiful side effect. Living on these cinematic sets, these devices started to seem like Pixar movie characters, each with individual personas and familiar, silent mannerisms. After a while, I developed a kinship with them.

When you’re working with green screens and CGI, it’s actually your job to merge with technology. I think people fail to understand how surreal that process is, when you’re attempting to feign humanity or realism in a staged simulation, within the bizarre, otherworldly structure of a production – where nothing is what it appears to be. Even language is distorted.

Right! And that language is so specific, and often poetic. That’s where the title comes from. The director would constantly scream: “Can I have more atmosphere, please?! We need more atmosphere in the shot!” You’re standing on your mark and suddenly you’re enveloped in this steam or smoke, which translates to the camera in a very creamy way to make the scene look more deep or … atmospheric!

There are also people with job titles like “best boy” or “key grip,” and lingo specific to the lights. Lights with yellow gels on them are called “blondies,” and ones with red gels are called “redheads.” I think they often use female names for tech and equipment because they’re usually operated by men.

And these blondes and redheads also “wear” shower caps, judging by your paintings?

It’s mostly the more delicate parts that “wear” them – the Tera Deks, which are WiFi routers, or Lilliputs, the little reference monitors. They need to be protected from moisture and rain, so they’re wrapped up, almost like little princesses. In this series, I was trying to create a kind of Ahnengalerie for these tech-characters – you know, those rooms in old castles where portraits of all the royal family members are hanging on the walls? “More Atmosphere!” is like the grip+gaffer department version of that. I almost feel like the court painter of streaming platforms.

Why did you gravitate toward the grip department? Is that who you spent the most time with during production, or was there something intrinsic in their personalities or process that resonated with you?

I found the grips and gaffers to always be really smart, kind, and dedicated people, and I felt grounded with them. They somehow helped me survive this production. I’m an insomniac, so when many of the other actors were back in their trailers sleeping and waiting for their scenes, I hung out on set.

I think because I’m a visual artist and not an actress, by study, I was especially fascinated by these rigs and tripods as objects, and was curious to understand how they work. They do such hard work and are so crucially invisible, in a way. They’re never in the shot, but they’re always making the shot. These objects are so scratched and scuffed up from being dragged around from set to set, and they’ve seen so many scenes unfold and so many directors flip out – almost like trees that have witnessed many wars. And as I spent time with them, they increasingly seemed to possess for me a strange and stark presence, like loyal entities, forever making the production.

It’s a funny dichotomy, actually. We use things like RED cameras and are doing incredible things in CGI – sometimes even in three dimensions – yet we are still beholden to iterations of the same basic analogue tools that we’ve used for 100 years. As an actor, you’re the human bridge between our base reality and this imagined, cinematic one – a mediator.

I often joked on set, “this is what streams are made of!” It’s such a dad joke, I know. But I love that this partly analogue and old technology – the clamps that attach the gels to the spotlight shields, which are called “barn doors,” or the gaffer tape that holds things together at the very last second – is used to make this slick and perfectly curated digital media. The equipment actually reminded me so much of our scrambling from output to output in our own freelance lives, which are often also very improvised and barely held together, behind the scenes.

Sets like the one you painted might seem dissociated from reality, but they have huge implications for day to day life. These massive media conglomerates create, and therefore control, the narratives that shape our understanding of ourselves, each other, and the world around us. They blur the distinctions between man and machine, analogue and digital, reality and hallucination. They even impact our ability to distinguish what feelings and ideas arise from within versus what narratives, values, and opinions are projected onto us.

I’m often thinking about the dramatization of our lives. When I’m speaking English, which I always do with my partner and most of my friends, I often feel like I am just copying and pasting language from American dramas and TV shows. I grew up in the German countryside in the 1990s and early 2000s, surrounded by all of these mediated images that were very US-centric, but only available German-dubbed. We learn from our surroundings, so now even my most private language feels artificial, because it’s influenced by the high-realism dialogue of Succession or Girls – of shows where everything is so snappy and perfectly scripted. By incorporating this way and rhythm of talking into my ESL lifestyle, I’ve started to find myself emulating these characters. I’ll be having an argument in the kitchen with my partner and be like, “Fuck this! I can’t do this right now!” – as if I’m a member of the Roy family on Succession. I feel like I can’t be for real anymore!

Credits

- Interview: Cassidy George

- Artwork: Britta Thie