Les Démons de Midi: LUCA GUADAGNINO and CARLO ANTONELLI are Friends, Talking

|Carlo Antonelli

Luca Guadagnino, director of I Am Love (2009) and Call Me by Your Name (2017), has taken on interior design – a long-time dream pursued (mostly) quietly over the last few years, in the homes of his friends and his own. Guadagnino officially came out of the shadows during Milano Design Week last month with a solo exhibition for Fuorisalone. Staged at Milan's Spazio RT, the two-room installation's geometric wood wall panels and La Manufacture Cogolin carpets were lit by original and archival sconce designs. The focal point in each salon – a fireplace – explained the presentation's warm, if slightly unseasonal name: "By the Fire."

Guadagino is not known to shy away from explorations of interiors and intimacies. He certainly didn't when journalist, producer, and old friend – of his and of ours – Carlo Antonelli called to scrutinize the intentions behind this expanding design practice. But both fireside and under fire, Guadagnino's creative practice, like the two Italians' friendship, lights up.

Carlo Antonelli: In addition to everything else you do, you've recently thrown yourself into interior and product design. What gives you the right to literally invite yourself into other people's houses?

Luca Guadagnino: In what sense?

CA: Let’s see. You are a vampire, and you can only feed once you enter the house. Who opens the door?

LG: Well, I always thought that the greatest vampire stories were the ones where people ultimately give in to being.

CA: Okay, who are the victims then?

LG: They're not victims; they're accomplices who like the idea of something deep and unprecedented on an aesthetic level.

CA: And what venom are you injecting them with through the bite?

LG: A sweet poison of craftsmanship and pursuit of form.

CA: What gives you the right to an opinion, even, in the field of design?

LG: Well, I hope I'm not giving one, honestly. I hope I'm not an opinionated person. Opinionated people are usually so categorical in the exercise of their ideas. I, on the other hand, always like to change my mind and cultivate doubt – or at least, I like to think so. When you work for someone, for example – even beyond the vampire metaphor – you listen deeply to what this person desires. And you must translate that desire into something that becomes a place. You cannot be categorical.

CA: You sound so commercial right now.

LG: You cannot be categorical, because if you are being categorical you aren’t listening to anyone.

CA: Let's say that the door was opened for you, and you walked inside, but instead of being new to vampirism you had been practicing to be a vampire since you were born. And by vampirism, I mean the field of design.

LG: I’ve always loved the idea of this, actually.

CA: Since when?

LG: Since I used to move the furniture around in my mother's house when I was a kid.

CA: In Ethiopia or in Palermo?

LG: I remember doing it in Palermo when I was about 7 or 8 years old.

CA: And you were redesigning the house.

LG: Yes. This one here, that one there, etc. I was doing that all the time.

CA: Does anything from your childhood in Ethiopia factor in? The different scale and structures of living?

LG: My experience in Ethiopia is of a petty bourgeois, part of a family that had moved there because my eccentric father wanted to travel the world. We lived in a small villa – sure, it was different from what a petit bourgeois family lifestyle in Italy might have looked like in those years. But it had nothing to do with some exotic colonial fantasy. Maybe the vastness was relevant to my conception of space, or maybe the light there was relevant to my idea of the function of light in space. But the same conversation about light followed us to Sicily because it was about light in hot climates – about what needs to be closed and shielded at what times and opened and enjoyed at others.

CA: Is that a light that has been turned on in your cinema?

LG: I am absolutely convinced of that, yes.

CA: So it is a southern light – as Callois put it, le démon du midi?

LG: It is a southern light, definitely.

CA: People have been known to talk about your authoritative personality, in a somewhat legendary way. Do you agree that this is the case in the film world, and would you say it happens in the design world as well?

LG: Who talks about me as an authoritarian personality?! I swear, I have heard a lot of people describe me in a lot of ways, but I have never heard myself described as an authoritarian person, ever.

CA: What have you heard?

LG: I may have heard that I am a commanding person, but that is unfortunately the nature of the work I do.

CA: It's the literal meaning of "director," after all.

LG: And how can you make a film if you don't direct? If you don't give directions? Of course, one attempts to do it in a maieutical way, but ...

CA: What about in your design approach?

LG: In design projects, I really like to stimulate ideas in my collaborators and make them autonomous.

CA: The other thing people say about you is that you are a crazy visionary.

LG: Eh, even then, you must understand what it means to be called a “crazy visionary.” That is, the crazy visionary is a person who imagines worlds that are disconnected from a typical sense of reality – worlds that are impossible, unreachable, and just not happening. Or do we mean quote-unquote "crazy visionary" in the sense of practicing utopia or of practicing possibility in impossibility? Maybe. I guess in my case it would be the latter. Because in the end, the things that I want to do and have the vision to do, I do.

"A sweet poison of craftsmanship and pursuit of form"

CA: Is there anything you have been unable to do, out of everything you had dreamed of doing as a child?

LG: Honestly, I have basically done and am doing everything I always wanted to do as a child. I’ll say it. I dreamed; I knew what I wanted. If one knows what one wants, one is already halfway there. The rest is simply putting, like, five-year plans into place.

CA: There’s a club night in Rome at Angelo Mai called Merende, which has a sign when you walk in that reads, "Come and get what you deserve: everything."

LG: I think that’s exactly right – but this slogan is a refrain you have to sing not in a key of consumption, but rather in a key that deflects precisely that, into a critical subversion.

CA: Might we say, though, that what you’re currently working on is more… decorative?

LG: I don't think so, no. We’re working with space; we’re shaping space. We’re not called upon simply to decorate a space, but really to make it. Several projects have begun with the radical redecoration of a space, but that has always just been a starting point. We’re working with high craftsmanship, making things that must be unique, making one-of-a-kind pieces. The concept of "handmade” is something that will never go away. It is classic.

CA: Do you think there is something exquisitely erotic about the way you design environments?

LG: I like the idea that it can be considered an eroticism – on one hand it’s austere, and on the other there is a sense of voluptuous and unexpected pleasures. I’m reminded of the character in that wonderful Barbet Schroeder film Maîtresse, starring Bulle Ogier – whose character certainly had a beautiful, very bourgeois apartment.

CA: So what did you do during Salone? More gate-crashing?

LG: We did not invite ourselves to FuoriSalone! We had been chatting with our friend Antonio Tabarelli, whose gallery Spazio RT is on Via Fatebenefratelli, which is very close to where I live. And during one of our flâneur chats – having a flâneur chat is one of the things I love to do the most – Antonio suggested that that maybe, after five years of designing, the time had come to share some of what we had made. We thought, why not? Plus, I'm in Boston right now shooting a film. So, it was a perfect opportunity to be there without having to be there.

CA: What are you shooting?

LG: I'm making a film about the tennis world. It’s called Challengers.

CA: And what did you make at Spazio RT?

LG: We occupied it, as it were, by completely changing the space. We channeled the memory of a historic installation by the great Carlo Scarpa, paying homage to him in a kind of remake – which is something else I love to do. So, for this kind of reactivation of an exhibition space à la Scarpa, we created two halls, two living rooms with fireplaces as centerpieces – one ceramic, the other of stoneware logs – that are completely anti-historical practices. We created wall panels conceived according to our own practice, and we asked the amazing art director Nigel Peake to design our rugs, which we reworked in collaboration with the Cogolin manufacture – easily the greatest rug maker in existence.

CA: Had you worked with Nigel before, in film?

LG: I started working with Nigel in the space of architecture, but then I summoned him to do the typography and graphic work on my television series We Are Who We Are. We also invited Francesco Simeti, an artist who I love very much and with whom I share a very powerful, very strong relationship. A biographical bond unites us because we both migrated from the south to the north – I from Palermo to Milan, and he from Palermo to New York. That background has given us an almost familial bond, and so has our common passion for ceramics. Francesco works with many mediums, and with ceramics he has made some of the most beautiful things. And we exhibited some of these.

CA: Was the idea or the hope to sell everything?

LG: More than selling everything, the hope is that some of these pieces would become rare, iconic forms in important houses.

CA: Are you sure this isn’t about the riches of Croesus?

LG: You mean, like, trying to acquire material wealth? To “get rich”?

CA: Yes.

LG: No. The practice of interior design and architecture does not produce that kind of wealth right now. It makes us rich in doing the things that we, my architects and I, love to do.

CA: But it will make money. Anyway, let's make a list of the things you have in planning right now.

LG: With the studio? We're doing a penthouse in Milan, a villa at the Venice Lido, a hotel in Rome, the offices of a large film agency in Los Angeles. We have completed a historic home in the Piemonte countryside and are about to start on a two-story apartment in Palermo. We are also developing some specific objects for some great artisans working in glass, porcelain, carpet weaving – among other things.

CA: For FontanaArte, for example.

LG: For our first collaboration with our friends at FontanaArte we designed a wall sconce representative both of our aesthetic and of FontanaArte's signature designs. In the coming weeks and months, the piece will be the point of departure from which to generate an entire line ¬– sconces, abat-jours, floor lamps and chandeliers – for FontanaArte. We are calling it "Frenesi."

CA: What defines “Frenesi”? Is it a wave? A ribbon?

LG: It is an undulating streak that makes one think of the pleasures experienced in one's life.

CA: Excuse me?

LG: It must make one think of the pleasures one has experienced in one's life. Because when vertical strictness is broken by a sensual ripple, it makes me –

CA: It makes you think of the past?

LG: It recalls the pleasures that you may have experienced and maybe those pleasures you want to experience, becomes it makes for a very sensual object.

CA: What happens when one of your lamps enters a house? Are you thinking of filmmaking or are the two activities separate?

LG: They are completely separate.

CA: How many things can you think about at once?

LG: Several, to be honest. I've figured out how to compartmentalize time – in the last few years and I’ve started practicing a compartmentalization of time and attention down to the second. That is, if I know that I have, say, 80 seconds to do something, I do it in that time. Then I resume the thing I was doing beforehand.

CA: Meaning?

LG: If I'm doing an interview with you, maybe while you're asking me a question and I'm listening, I can have a thought about something I have to do later at the same time. I think I've developed this ability to multitask, to use a horrible word.

CA: But how many levels do you think that has? Are the layers endless?

LG: No, no, no – it's just a way of being. That's the way I am.

CA: Who did you learn it from? No, you didn't learn it, you have been developing it over time!

LG: You know, before, I couldn’t do the things I wanted to do. I was simply a daydreamer. Now I want to be someone who gets things done. As I already mentioned, the practice of utopia is the practice of making the impossible possible. And that's the only thing I'm interested in.

CA: Then it’s over, from a certain point of view. You’re done.

LG: No. Who knows what's going to happen. You haven’t asked me about the cinema I've seen recently. We could talk about new releases! This would have little to do with the practice of interior design, but yesterday I went to a movie theater that was bursting like an egg to see the new Tom Cruise vehicle Maverick and I was struck by the movie. And above all by the participation of the audience, which was completely and absolutely thrilled, captive to the ideas, or better yet to the ideology, of the movie.

"A sense of voluptuous and unexpected pleasures"

CA: You know, the cinemas in Italy are all still empty.

LG: I do know. Italy is a special case though; the US is not. Maverick has a very strong nostalgia – meaning it has the same nostalgia that was already felt within the first Top Gun, in addition to nostalgia for the first Top Gun itself. As a practice, I have to say that this is perhaps the most poisonous thing you can put into place. If you want to talk about things I don’t like doing, what I don't like to do is to give the nostalgia effect.

CA: Let’s look ahead then. If you could, would you design entire parts of town, parts of cities?

LG: Five or six years ago, I got a proposal from my Hollywood agency to participate in Mohammed bin Salman's visionary, massive idea to create a city from scratch, called “Neom.” Architects and filmmakers from all over the world were being asked to contribute their ideas to create neighborhoods, streets, buildings. When the proposal came to me, my immediate response to the agency was: “Are you sure you guys want your clients to cooperate with a regime like this?” A few weeks after that the great journalist Khashoggi disappeared, and then it turned out he was chopped up at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

CA: Who are the architects you are working with and what are the criteria for working with them? Other than not being in the service of an authoritarian regime?

LG: I work with a number of architects. There's a wonderful team in the studio, assembled over the years, of people to whom I hope – and I think they would attest to this – I've given the freedom to express what they feel compelled to express. They are not simply “doers,” they are people who inspired me and who, I think, I also inspire. Anyway, I love each and every one of them.

CA: Do you know that one of them responded anonymously that he hates you?

LG: It’s not true that he said that, you liar!

Credits

- Interview: Carlo Antonelli

- Photography: Giulio Ghirardi

Related Content

Streetwear’s Secret History: A Journey with LUCA BENINI from the Last Days of Italian Disco to the Launch of Archivio Slam Jam

LOVE! INSTAGRAM! COMPASSION! Between an Ipanema bikini and an over-decorated cake, FRANCESCO VEZZOLI's Love Stories

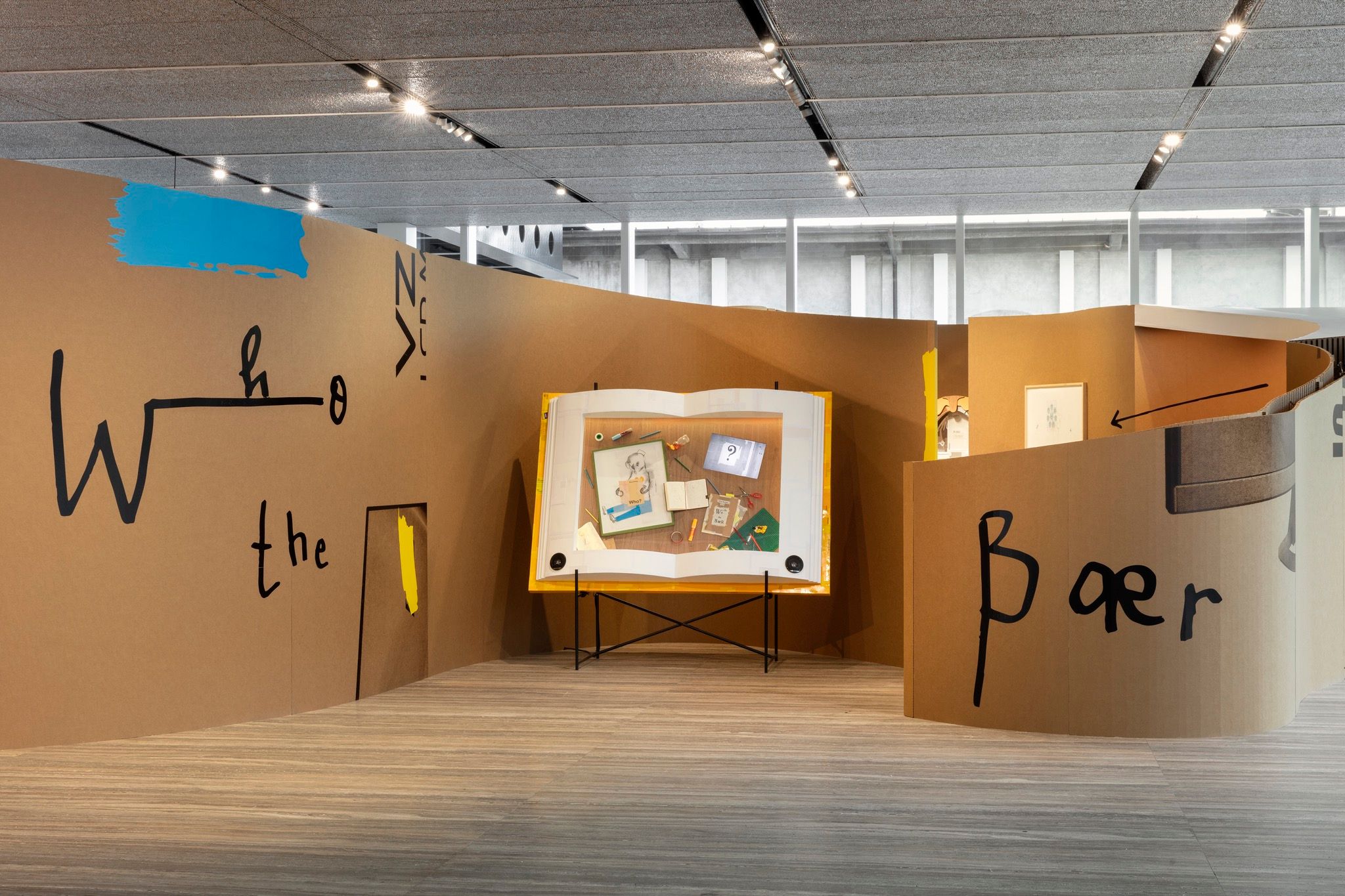

Who’s Who? SIMON FUJIWARA at Fondazione Prada

FUORI: Outside in Rome, Art Draws Breath

Elmgreen & Dragset: Useless Bodies