Who’s Who? SIMON FUJIWARA at Fondazione Prada

|Andrew Pasquier

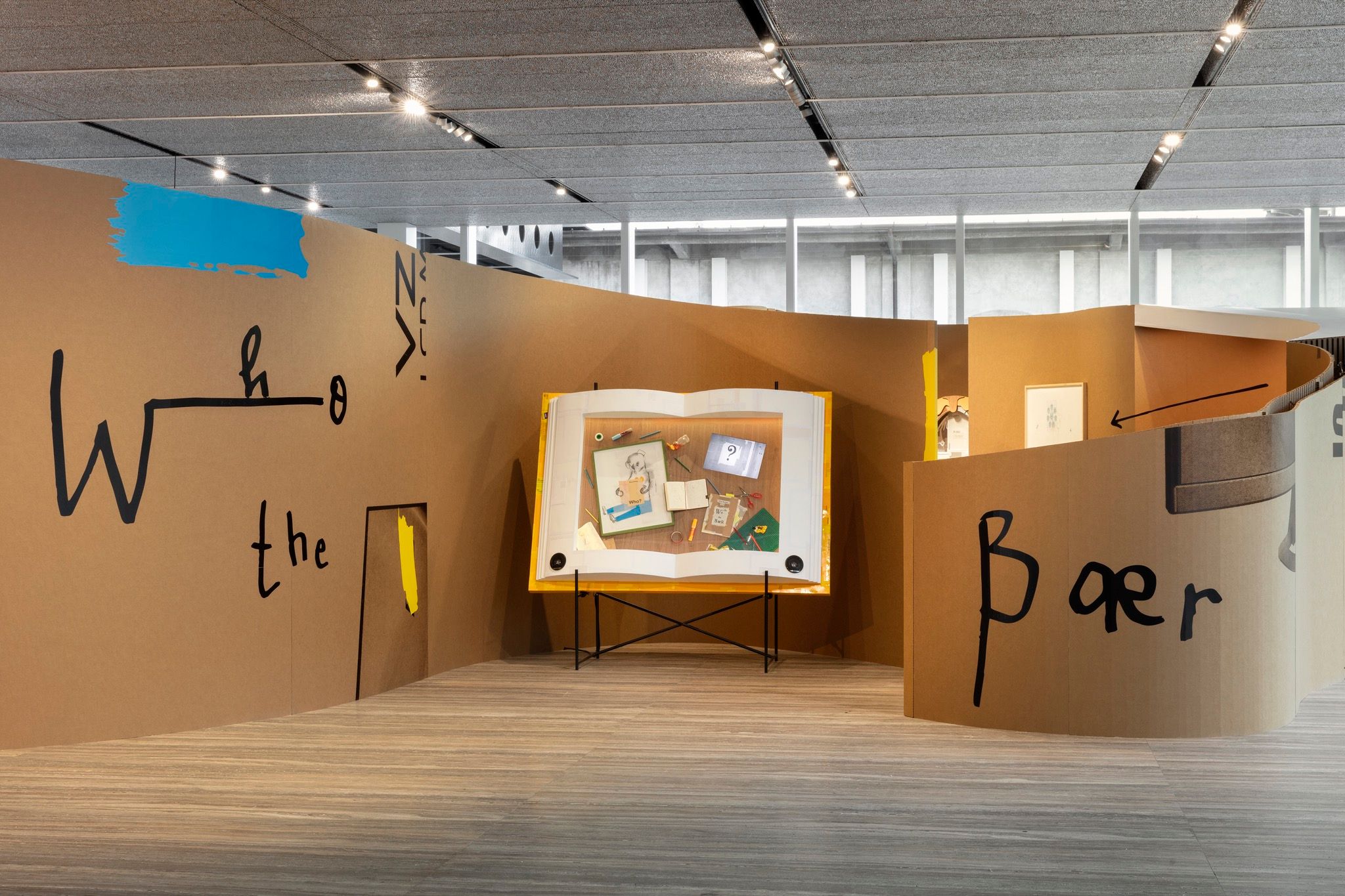

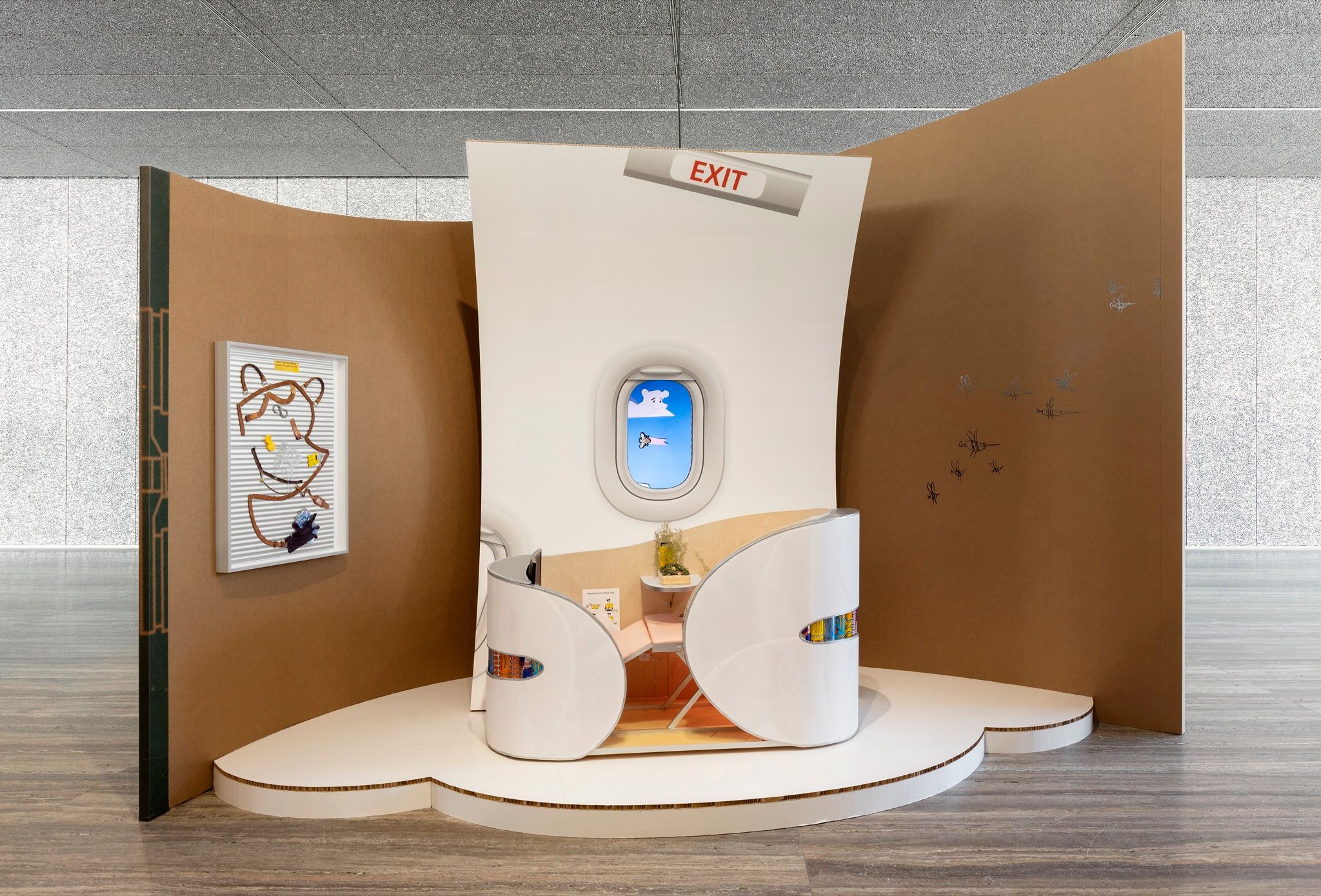

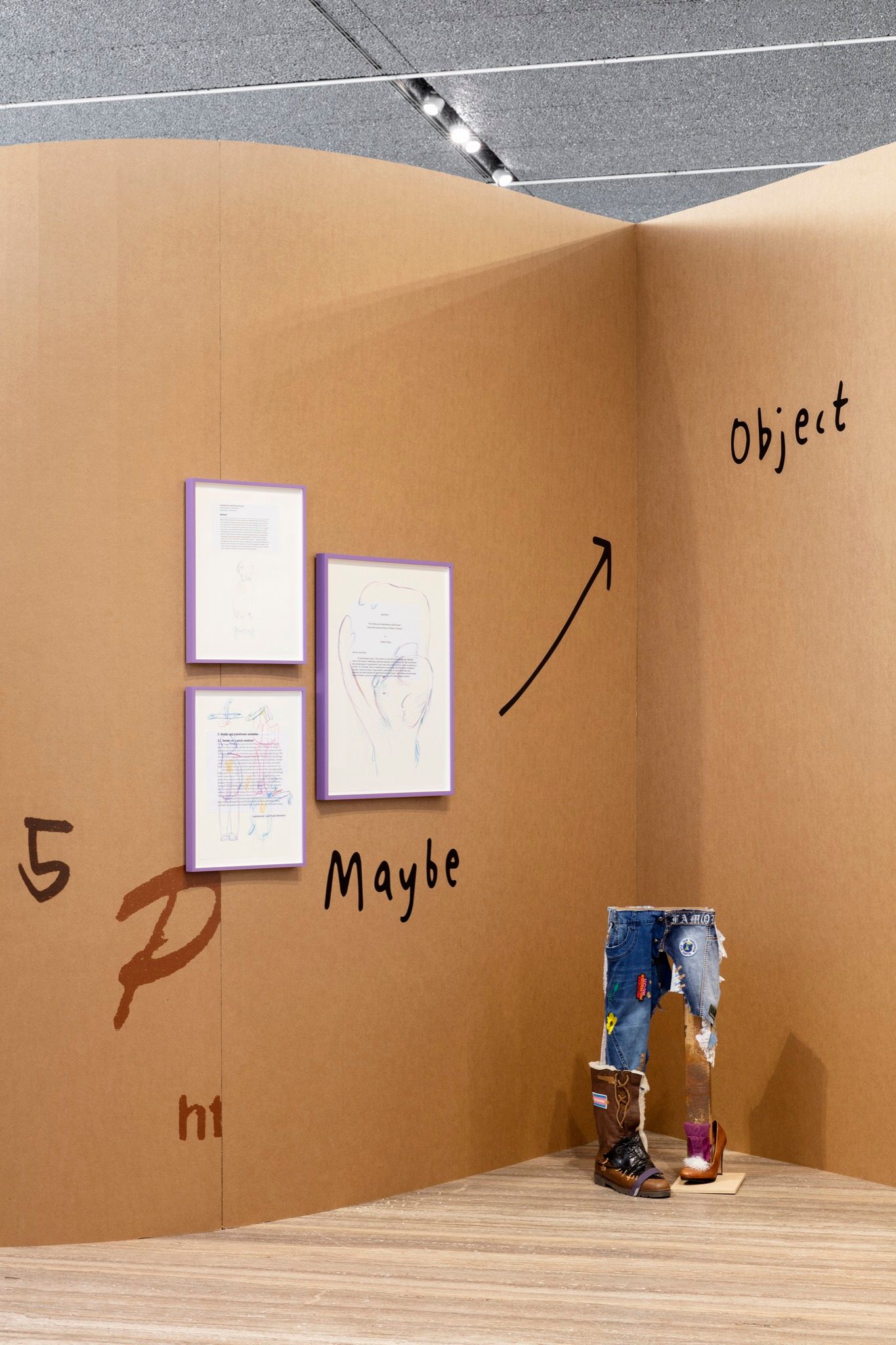

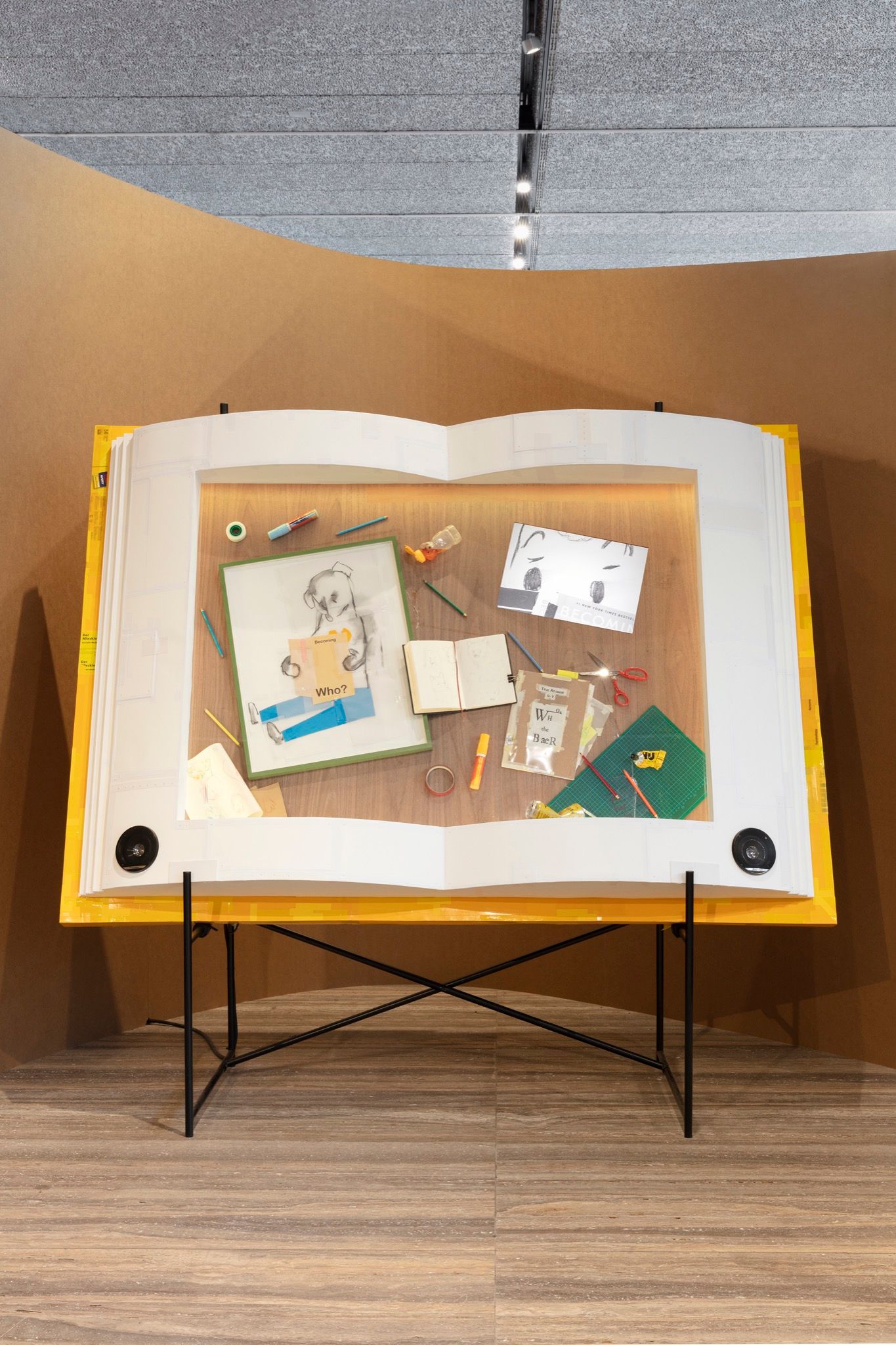

For the past few months, a series of labyrinthine, cardboard walls have occupied the ground floor of the Fondazione Prada in Milan. From above, the unlikely exhibition design takes the shape of the equally unlikely star of the Fondazione’s current show: a cartoon bear named Who the Bær. Conceived by the British-born, Berlin-based Simon Fujiwara during the depths of lockdown, the childlike figure helped the artist to filter an increasingly frightening world through the safety and simplicity of a cartoon figure.

Moving through the exhibition, viewers encounter a melange of sculpture, collage, and found objects that reveals Who’s voracious appetite for images. The coming-of-age journey takes visitors through space and time as Who brashly appropriates – or literally embodies – the icons of history, the digital ephemera of the meme area, and everything in between. Who becomes an Easter Island statue in one episode, before taking the form of Obama in a restyled “WHOPE” poster in another. As a protagonist without fixed gender or origin, Who’s shifting identity is a vector for Fujiwara’s own experimentation with our image and identity-obsessed culture.

In our conversation this spring, Fujiwara emphasized the philosophical dimension of Who’s search for an authentic self. He urged that Who is a helpful companion not only to the character’s creator, but to everyone attempting to navigate what it means to be “real” in an image-saturated world. The show in Milan closes this month, but Who’s universe will live on in a special online mobile experience developed by Fujiwara, complete with stop-frame animation and a digital re-creation of the striking exhibition design.

ANDREW PAQUIER: You started this project when the world was on lockdown last spring. How did “Who the Bær” evolve from initial sketches into the architectural and artistic journey that is on view at Fondazione Prada?

SIMON FUJIWARA: During lockdown, I started to think apocalyptic thoughts. “What if I can’t ever travel again? What if I can’t produce art in the way I did before? What kind of artist would I be?” I began to fantasize about a way of dealing with larger questions with minimal means – the hand, the pencil, and the printer – and to collage and draw cartoons. I saw that everyone else was regressing, making banana bread or doing quiz nights with family. I guess my form of regression was to try to filter the world that seemed increasingly scary and complicated in the simplest and safest of ways: through a cartoon reality. Who was a playful tool to make sense of everything happening.

The design of the exhibition is quite striking: a series of curving, labyrinthine walls made of cardboard that form the shape of Who the Bær, the show’s protagonist. What inspired it?

Everything about Who the Bær is direct, simple, and unfiltered. So when it came to designing the architecture of the exhibition, I had to go with the first thought that would come into a cartoon bear’s head, and that would be to put the whole exhibition into a giant bear-shaped structure. I thought of Frank Gehry’s work because it’s so iconic and consumable. I wondered what Who the Bær would do with Gehry, and ended up with a giant cardboard labyrinth shaped like the character, which also felt reminiscent of Richard Serra. I liked the idea of a Frank Gehry building made of cardboard because philosophically, I like seeing things that seem to be perfect images as somewhat taped and glued together behind the scenes.

“I wanted to create a subject that could illustrate the power and violence of images, and who could embody this extreme proposition of the world as just a picture, devoid of authenticity.”

This design approach aligns with the spirit of “Who the Bear” and the adolescent optimism reflected in the arts-and-crafts, DIY materiality of the work in the show.

Exactly. Who the Bær thinks, “Oh, that’s Frank Gehry. I could do that.” Who’s attitude was inspired by how we form identity today, a kind of tin-pot optimism blended with a desire for instant gratification. An idea that Who is excited about – like a Frank Gehry building – can be made with just cardboard. It may be fake, but it doesn’t matter. Everything now seems to be about effect anyway. There’s a philosophical question embedded in this approach. “It’s not the real thing – or is it?” The whole world feels like a conceptual artwork at the moment.

What was your initial inspiration for the cartoon itself?

I wanted to create a subject that could illustrate the power and violence of images, and who could embody this extreme proposition of the world as just a picture, devoid of authenticity. Through Who, I try to find new ways of talking about contemporary problems. One of the dominant issues for our generation is figuring out how to escape this mirror-circus of representation that we’re all stuck in. We are so obsessed with authenticity because all we see is hyper-representation of authenticity. We’re scrambling to figure out what is real in the world, and what is real in ourselves. Each individual is supposed to figure out who they are based on all the images they’ve been exposed to, yet at the same time, there’s supposed to be an authentic “you” underneath the image-based one. It’s a lie that underlies the fabric of our society. I thought, “How can I illustrate this point?”

As an artist, I really love images. My identity has been built on looking at pictures of the world. I’m gay and non-white, but grew up in a very white, rural town. My whole identity – or dream identity – was built on pictures and representation. One of the tasks I have had to tackle throughout my life is untangling my self from its representation. One of the tasks that gay men face, for example, is figuring out how to live in a heteronormative society. You look to representation in images because when you’re young, you don’t know anyone else that is gay, or at least I didn’t.

That’s one of the reasons the internet is so powerful: it’s a tool for discovering images that can help you discover yourself. But what do you think about the negative side of digital image culture? There’s a performativity to the way that people present themselves online.

“Who the Bær” reacts to this notion that we’re all trapped in a world where we know that images are really bad, yet we still want to look at them. People wonder, “Can I find the right image for this politics that I embody? Can I find the right slogan to represent how I feel about race, gender, or sexuality?” It’s not fun. The ethical left-wing, or whatever we are, ends up becoming so traumatizing because you, as an individual, are never right. You’re never doing it “correctly” enough. You’re never representing the right things.

Overall, this image culture is making things really simplified and unnuanced. I feel like the world is “cartoonifying.” Take Greta Thurnburg, for example. The end of the world through ecological disaster is told through a child. She is this icon with a braid and a sign and a yellow raincoat. She even points out the absurdity that the onus is on a child to make us aware of the impending global climate catastrophe. I have nothing against Greta, but she is like a cartoon. Then you look at our current roster of politicians and you realize they too are like cartoons, operating within a cartoon world. It wasn’t a big leap to think of making a cartoon like Who to talk about serious things.

“In previous generations, a child’s dream would be to be an astronaut, archeologist or baker. Today, it’s to be a brand.”

An important premise of the exhibition is that Who isn’t defined yet. Who has no set origin, gender, or identity at the start of the journey. Who is a blank slate that discovers the world with innocence.

Yes. Who is dealing with the world of images and how things are represented, but not necessarily with the issues themselves. Who is not trying to be authentic; they are asking, “How do I appear authentic?” In some ways it’s a reaction to how the Left has tied itself into this knot where everything is incredibly serious, while the Right is having all the fun going around saying whatever they damn please. I guess you could say Who embodies some of what we might call right-wing tendencies. But because Who has no explicit identity, these questions of identity politics, or politics in general, become somewhat dadaesque.

Well, it’s become so hard for adults to play with various identities that cartoons and mascots – say Pepe the Frog and Gritty – have become vessels for political experimentation.

Absolutely. I think we are becoming more and more infantilized, which might be a reaction to how complicated things are. People are able to express themselves through the language of childishness on a mass level right now. We’re seeing a deep simplification of society through cartoonish metaphors, a regression.

We believe so much in the image, and we believe so much in representation. I think it’s probably intensified under Covid because we have mostly been stuck at home with nothing but digital representations of the world. When you look at online activism, you see this “representation is everything” logic, which is very disturbing. Gwen Stefani wearing a bindi in a music video from the 1990s is now, through a revisionist history, thought to lead to a culture of anti-Asian hate. It’s simplistic, but in a world where the image is all-powerful, maybe it can be willed into truth, or at least into believability. “Who the Bær” tests this theory. What if it really is this simple, and the world is just a reflection of images?

So Who is an avatar that helps you sift through contemporary debates.

During lockdown, I went into search spirals on the internet and asked myself, “What would Who think about this?” I would be looking at some images of a Frank Gehry museum building, and then wonder what’s inside it. Then I’d read some comment about repatriating the Benin Bronzes and think, “Oh God, this is dodgy territory.” But what if Who wanted to be the Benin Bronzes? Who doesn’t understand the controversies, they just want to experience the world. Who offers me the freedom to explore all of these debates.

How did we become so colonized by images?

How much does Who’s journey reflect your own interaction with image culture?

On one hand, I think Who is an expansion [of my experience], and on the other hand, a total reduction. One of the core questions in my work is: “What is an individual?” We’ve grown up with this ideology of the individual, but it’s never felt right to me. For example, in my previous work I’ve focused on an icon, for example Anne Frank. We’ve created an industry around her that seeks to use a specific individual to encapsulate an entire narrative of terror and hope emerging from the Second World War. In previous generations, a child’s dream would be to be an astronaut, archeologist or a baker. Today, it’s to be a brand. Now, I think that being an individual isn’t enough. There’s this idea that we can produce ourselves, contain ourselves, and present as armored vehicles of the self. All of my work circles around this idea.

We’re maybe the first generation whose world has been so filtered through media, up to the point that facts don’t really matter anymore. We sanction entirely subjective ways of piecing reality together to form personal truths. Who offers a chance to exceed this individuality. Who is an attempt to not be consumed by this image world by being the ultimate image consumer. It’s a character that just eats and eats. That’s where their long tongue comes from!

There’s a Disney element to the way Who travels the world, consuming culture. It reminds me of Epcot’s digestible, cartoonish presentations of countries from around the globe.

It’s this tapas-of-the-world approach that’s very much inspired by old cartoons like Tintin, which were written from this white colonialist perspective of just dropping into a place, consuming it and spitting it back out. That’s also the culture I grew up in. The term “diversity” only really started to be used in the 1990s – and that’s where things got really taspas-y, as in, “look at how people in this or that country do things.” Some people think it’s degrading or belittling, and it’s true. But when you expect so little and are so desperate to be represented or seen, like I was, it was really exciting. I thought, “Oh my god, I might be one of the tapas now – but at least I’m on the plate.”

How does a “tapas” approach brush up against appropriation?

With “Who the Bær,” I was thinking a lot about cultural appropriation and repatriation. Who can talk about whom, and what, and how? Who travels the world and sees it from the perspective of dominant image culture, and dominant image culture was made from a white colonizers’ view. To be honest to the project, I had to take that perspective. For example, in Egypt, Who turns into a mummy, and their face is pasted on these photos of British explorers and archaeologists. By being both the perpetrator and the victim, Who can show us how complicated these debates are in a really simple way, by becoming everything. Who is looking for the easiest and the simplest images – and the easiest and simplest images are the ones made by white hegemony. And they were very, very good at that. In a way, I’m trying to reveal the mechanics of this gut response to images. When you say “Egypt” to someone, suddenly a flash of themed images appears that reflect dominant image culture. How did we become so colonized by images?

It seems like Who could be a helpful companion to many of us.

Who is a way of waking up every day and looking at something with fresh eyes. Who is a lens, a filter. Who is me and Who is you!

Credits

- INTERVIEW: Andrew Pasquier