Streetwear’s Secret History: A Journey with LUCA BENINI from the Last Days of Italian Disco to the Launch of Archivio Slam Jam

|Carlo Antonelli

In all likelihood, ten years from now kids will look back on all the excitement around t-shirts, clubbing, jackets, and sneakers that we’ve seen over the last three decades as an incredible error of perspective – a materialist whim disconnected from the urgencies of the real world. But there’s also a distinct possibility that something about this strange whirlwind was instinctively trying to find new ways of expressing the cultural mutation that we have witnessed surrounding the turn of the millennium – and to prepare us, through dress codes and musical sounds, to navigate new speeds of communication and new territories amid the constant, day and night search for self that is urban life in the advanced present.

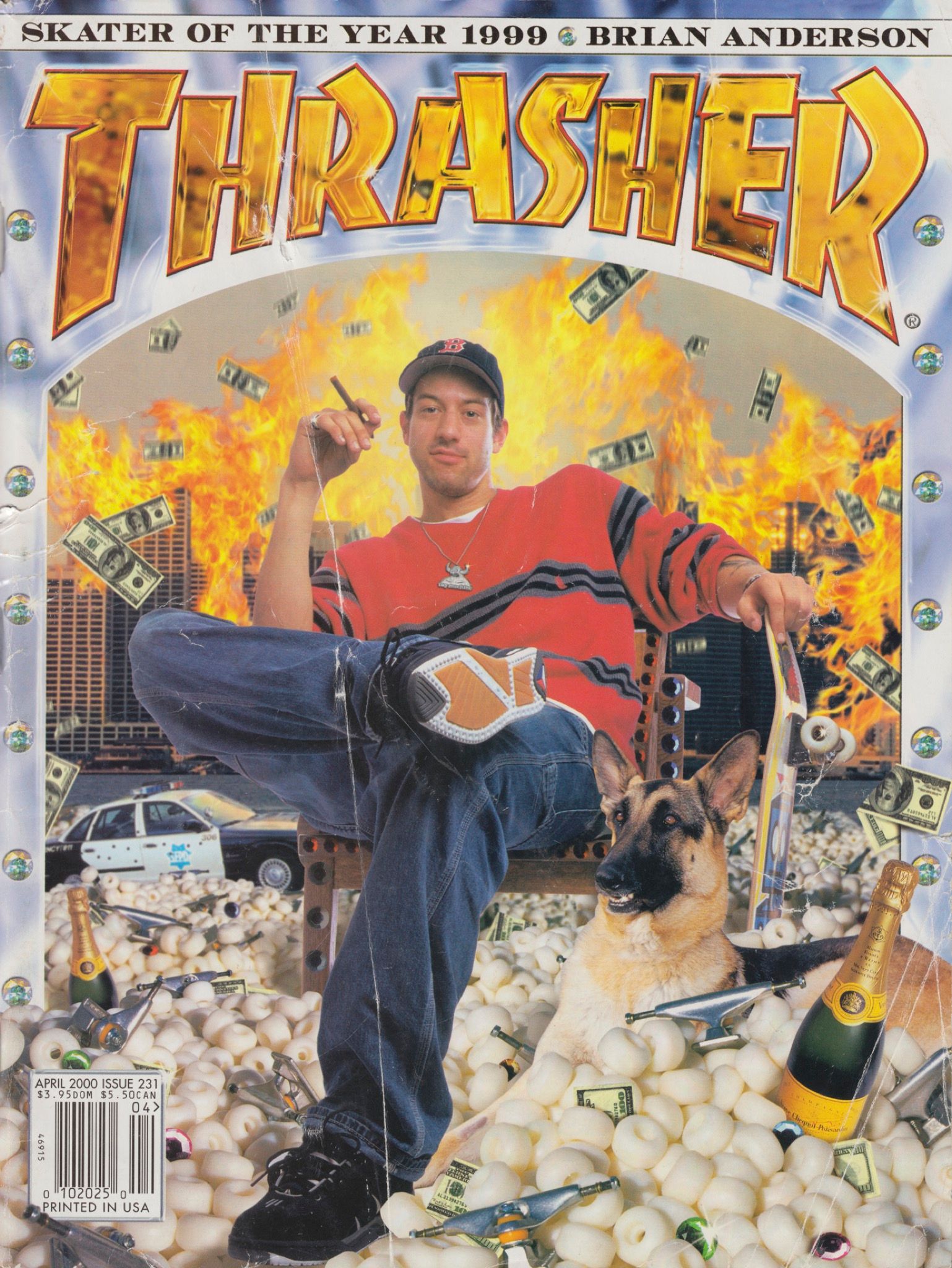

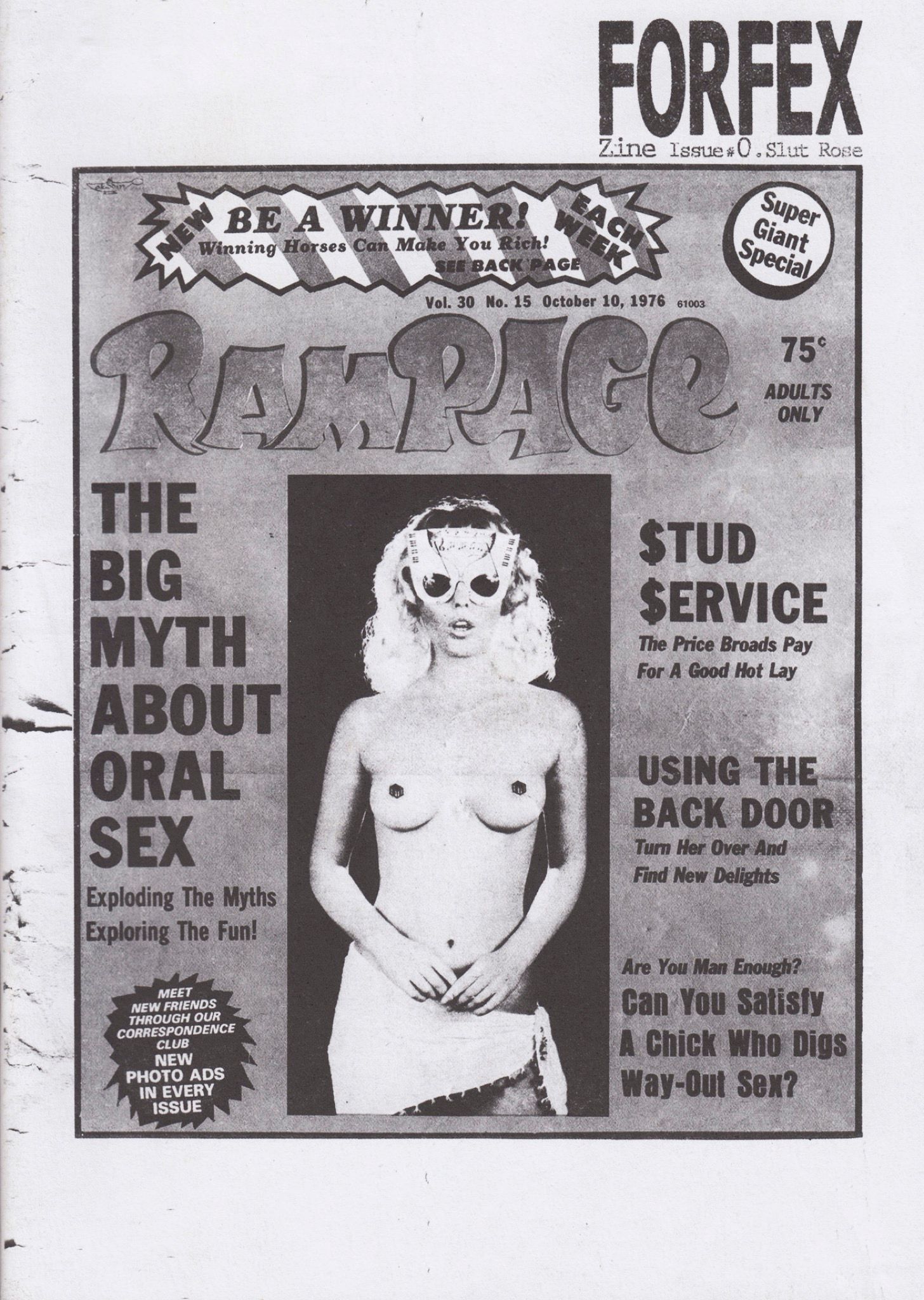

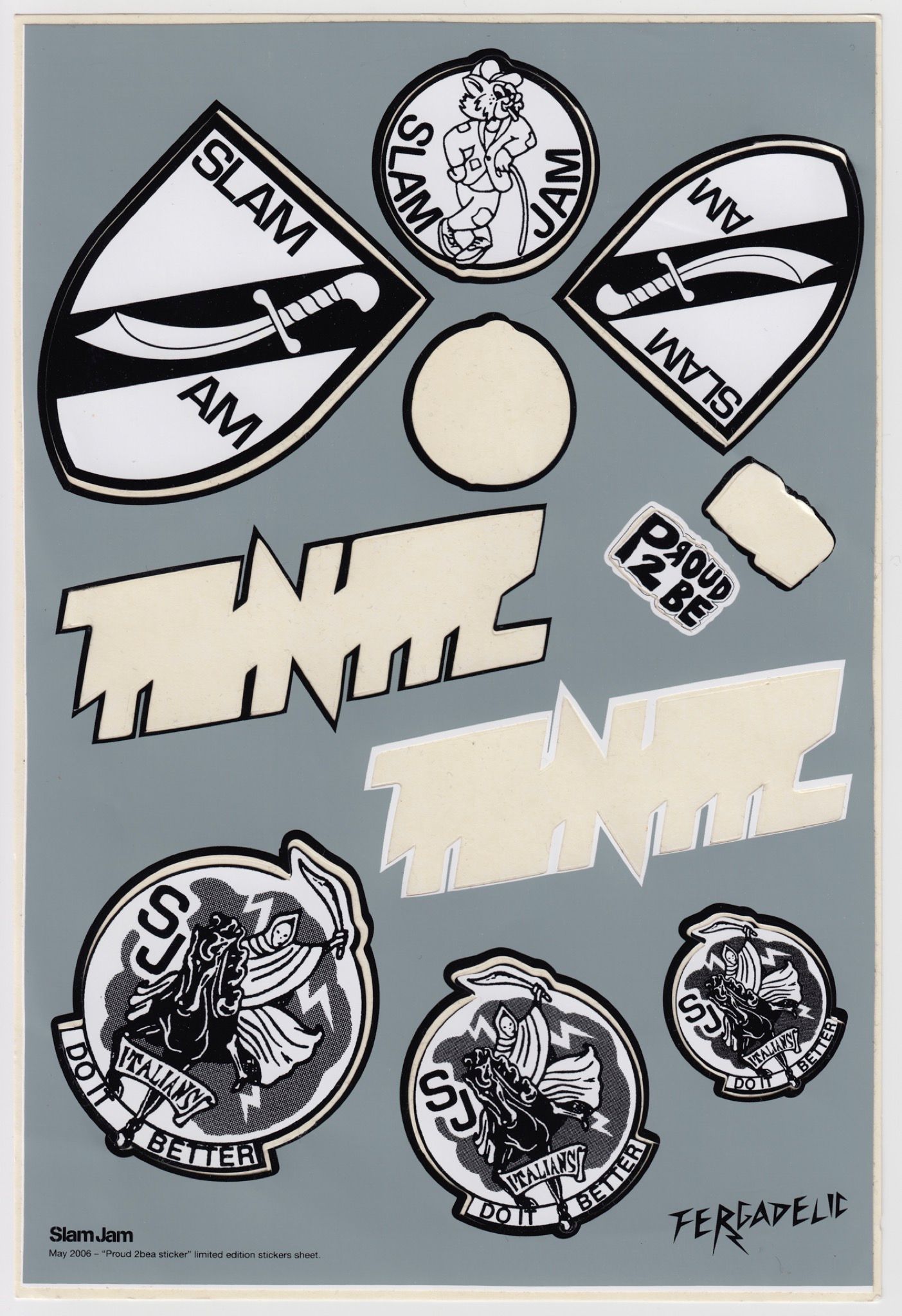

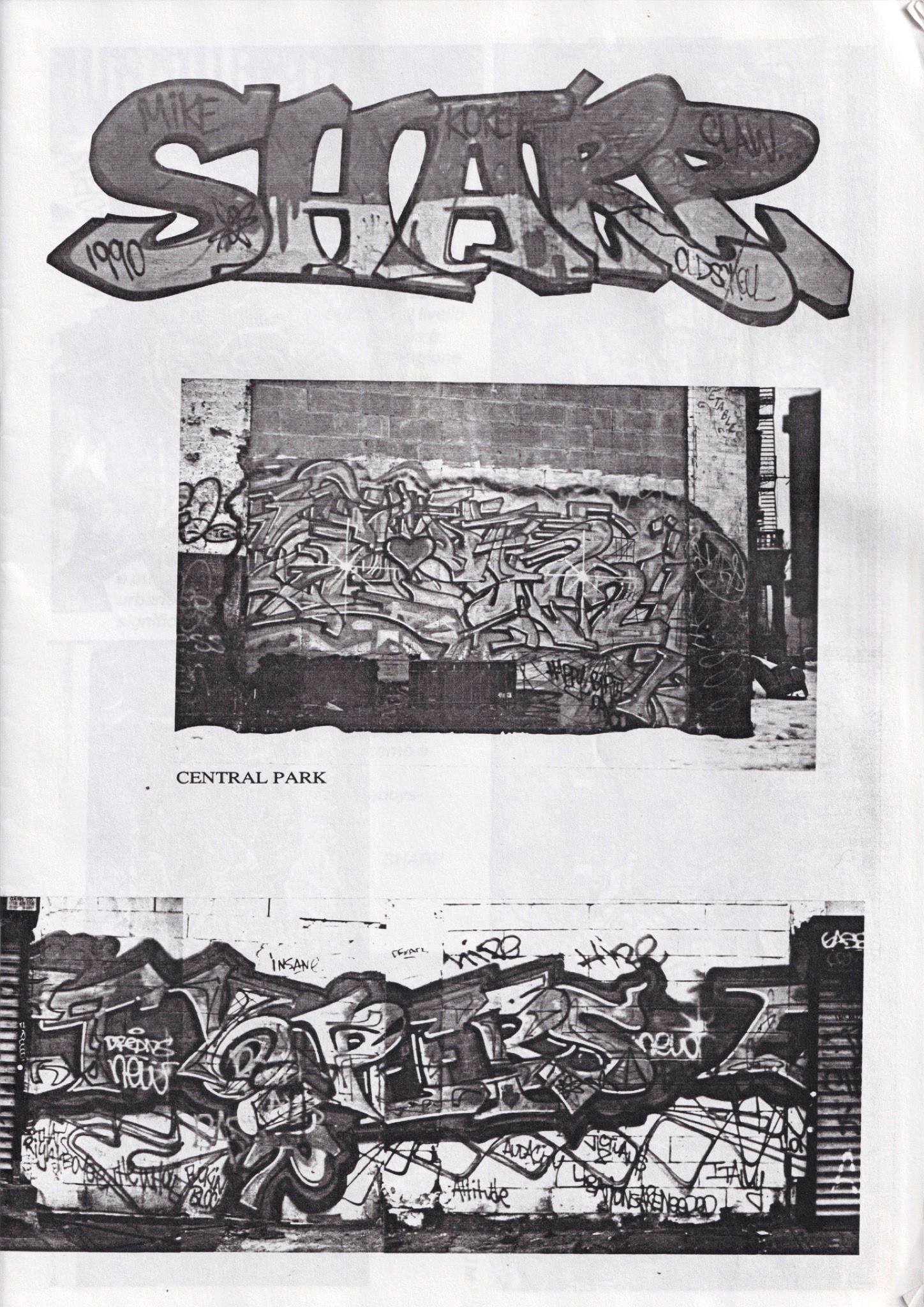

If those instincts were right – as instincts often are – one brand that followed them with particular foresight and vigor is Slam Jam: an incubator/dispenser of the aesthetic and language that would become known as “streetwear.” Founded by LUCA BENINI in a garage in Ferrara, Italy (which is smaller than Bologna, even) in 1989, Slam Jam considers its more than 30-year role as a fashion and subcultural prime mover by making its vast and complex archive – of vinyl records, art, and ephemera as well as clothes and accessories – accessible for the first time digitally. I immersed myself in ARCHIVIO SLAM JAM’s deep and liquid scroll – first alone, and then with Benini, who annotated the life contained therein.

Carlo Antonelli: You asked me how I was. I’m a mess, how you do want me to be? Everything alright with you?

Luca Benini: Yes, you?

But come on, we’ve been in fourteen-hour day working conditions sitting in front of our screens for a year. It’s not fun. I know I’m not saying anything new.

Eh, I know.

This spring we lost [the great Italian DJ] Coccoluto, who died at 59 years old. He’s someone you collaborated with, right? So I wanted to start with Claudio, not just to honor his memory – I knew him well, too – but to draw some lines back through time. How did you meet? How did the collaboration with Slam Jam come about? And what does playing records – and I do mean play – mean to you?

We did this collaboration for this party, an event in Tokyo two years ago. We chose Claudio not just for the discourse of internationalism, which he had, but above all for his personal and musical sensibilities. Claudio was born in 1962, like me – him in August and I in December – and he was struck, like I was, by a tape from Baldelli’s Cosmic [a legendary Italian club that emerged in the late 1970s/early 1980s, in the Veneto region] that a friend had given to him and that was the reason he decided to become a DJ. So in other words, we shared a passion for these four legendary DJs: Baldelli, T.B.C., Mozart, and Rubens. Beyond that, what it means to put on records – I don’t know!

Wait a minute – you were born in 1962, which makes you almost 60, right? That means you grew up in the 70s.

Yeah, in the late 70s and early 80s.

And as you know, the 70s were a very heavy period – being 12 or 14 in 1974 was like being 25 in 2009. And the scene in Italy was very special, very specific. What was it about that time? I imagine you never went to Cosmic.

How did you know?

Well, because you spoke about the tape. I have those tapes, too.

So no, in fact, I never went there. Let’s say that in 1978, seeing as my birthday is at the end of the year, I was 15 years old, so for better or worse I lived after the total decadence of those discos and that community, and it was some community. Going to Baia degli Angeli and then to Cosmic – that would have been an experience that went far beyond going somewhere to listen to music.

DJ Mozart was at Baia, right?

In 1978 you had Mozart and Baldelli, and in 1979 it was Mozart and Rubens. Then Baldelli opened Cosmic in May 1979, I think. Cosmic was born under the influence of Baia. But if you jump ahead to 1980, you can already hear the sound coming into its own distinct identity. Baia was, like, funky disco with a bit of electronic, while at Cosmic you had every level of sound, especially in 1981/82. I don’t know, maybe there have been similar phenomena since then, like Cocoricò [a monumental megadisco in Riccione at the turn of the millennium]. When that club opened in 1989, a new energy had already begun to overwhelm everything – music, clothing, lifestyle, everything. But as far as disco is concerned, by 1979 you really had to get away from that scene, because things got dark. Before that you could go to Baia and maybe smoke a little, do some LSD – nothing major, and always in the spirit of fun, music, connecting. After that it was all over. The only way people could connect was through a syringe. Lucky for me – and not because I’m smart, but because of the deep fear I had around it – I didn’t go down that path.

But it was everywhere, wasn’t it?

It was everywhere. And I had to keep my distance. That was the ugliest period: the music was over, and so was the fun. It wasn’t easy, to be 17 and find yourself alone, having to find new friend groups that aren’t the ones you belong to, going to clubs outside of the scene you belonged to, dressing in a way that wasn’t how you wanted to dress. But that’s what I did.

Sorry, how were you dressing before?

I dressed how everyone else at Baia dressed: worn-out jeans, long hair. I was hung up on this store in Milan – so much so that I even made a couple trips to go there – called Crazy Boy. Do you remember it?

No. Great name.

It was the store that Lino from Plastic opened on Viale Monza in 1979 [Italy’s most important club of the last 40 years, located in Milan but internationally famous – and still active]. You couldn’t find any other brands there, it was all stuff – sweaters, t-shirts – made by the people behind Plastic.

Like SEX, the store Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood ran in London.

Exactly! It had a structure entirely of its own. Anyway, after about three years of decadence and loneliness – which is never nice, even less so when you’re 18 – I found energy again with New Wave, dark, garage, and with the opening of Aleph di Cattolica. I’m sorry if I’m always putting out clubs, but those were the places where energy was generated.

No, I’m with you.

It was an important period, and I experienced it assiduously. And in those environments, there were definitely drugs – but not heroin.

Have you watched Sampa, the Netflix documentary about the San Patrignano recovery community?

Of course, during the premiere I spent 60% of the time crying. That’s what I am talking about when I say that the summer of 1979 ended with an atomic bomb: heroin. Remember in the series when Delogu, Muccioli’s right-hand man and bodyguard – a Sanbabilino skinhead from Milan – talks about how they would go out to buy hash and be handed “a bag for the syringe” as change, not knowing what it was? That says it all. I really think it was an operation from above to subdue everything that was going on at the time – the new political factions, terrorism, revolution – even if you weren’t involved in politics. It was as though it fell from the sky and just covered the ground.

So you’re at Crazy Boy, the store in Milan. You’re changing your look to get off the toxic merry-go-round your friends are on, to get as far away as possible. What clothes do you end up with? Best Company?

Actually, before I started going to Crazy Boy I worked in a store that sold Fiorucci.

Do you love Fiorrucci’s world?

Yes, of course. Then, in the 1980s, I got a job at a store that sold Saint Laurent – not the Saint Laurent of today, but the Saint Laurent trying to sell to 60 year-olds. So I had to start dressing differently. I couldn’t go in in the broken-in jeans; I had to wear loafers and pleated pants.

So wait, you didn’t go to Milan looking for Elio’s store? Hadn’t you heard about it?

Yes, sure, but I’m telling you, the first time I went to Milan, it was 1978 and it was specifically to go to Crazy Boy. At that time it took 4 hours and 30 minutes to get from Ferrara to Milan on the train! Either way, it didn’t take long to find Fiorucci.

The Fiorucci retail experiment remains unique, I’d say, with its street-level pop-ups and people spinning vinyl in the display windows, Keith Haring paintings all over the store, et cetera. It was a complete universe. Anyway, do you like them?

Like what?

Clothes and records.

Ha, sure.

How did you do it?

Do what?

Stay straight in the way you did for all those years.

I think what really saved me, in all my despair, was losing my friends, the disgust I felt at school while being disparaged by my relatives – not by my parents, though – and compatriots. I was born in a small town of 1500 people, so if you were even just a little different you were already doomed. And I was very different! The thing is, I didn’t give a shit what anyone told me, because I already knew what I wanted to do: sell clothes. That force was strong enough to help me get over all the disappointments.

How did you catch onto things, I mean where were you getting your information? Magazines?

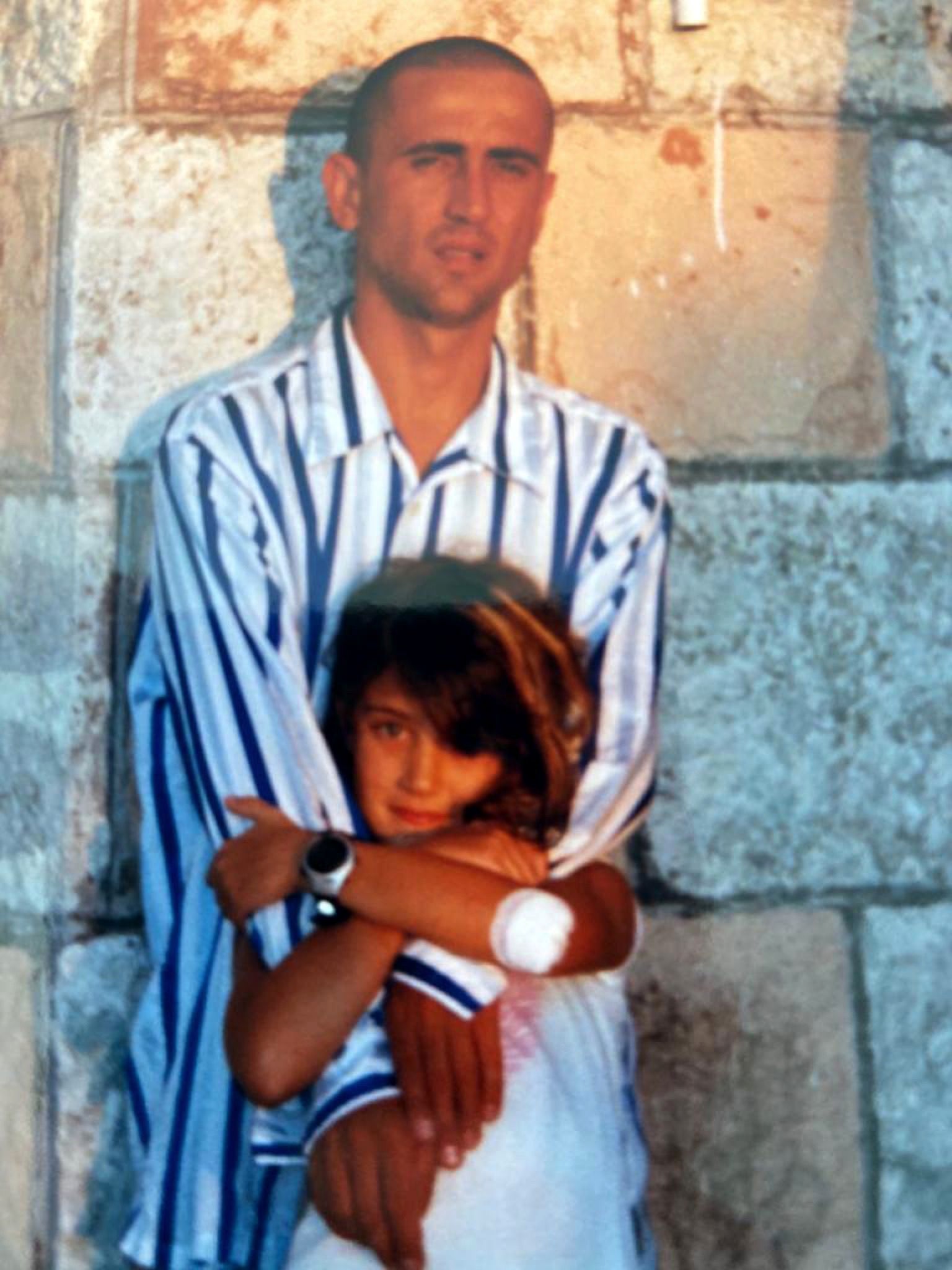

Someone actually said to me the other days, “You did so well, you had the sensibility needed to find things.” But real sensibility, I realized only last week, is first about being able to identify who to listen to and to follow. That’s so much more important than having a sense for being able to choose a brand like Stussy. There were people around me who I just sensed I had something to learn from. I also had a cousin. He was 20 years older than me and worked in Bologna at Centergross, a company that was mainly doing women’s fashion, but always somehow brought something new. He was first person I ever heard say he was “in love” with something. With what? It was the summer of 1979 and I’ll never forget it. He said, “There is a designer who I think is out of his mind.” Who was he? “Giorgio Armani.” I would never have considered Armani in 1979, but a year and a half later, I discovered I could: that’s when Emporio Armani came out. That was a very important moment to me. Another one was in 1982, with Massimo Osti’s Stone Island, and later C.P. Company. There are two other Italian realities that, after Fiorucci, have truly influenced me.

When did you start going to London?

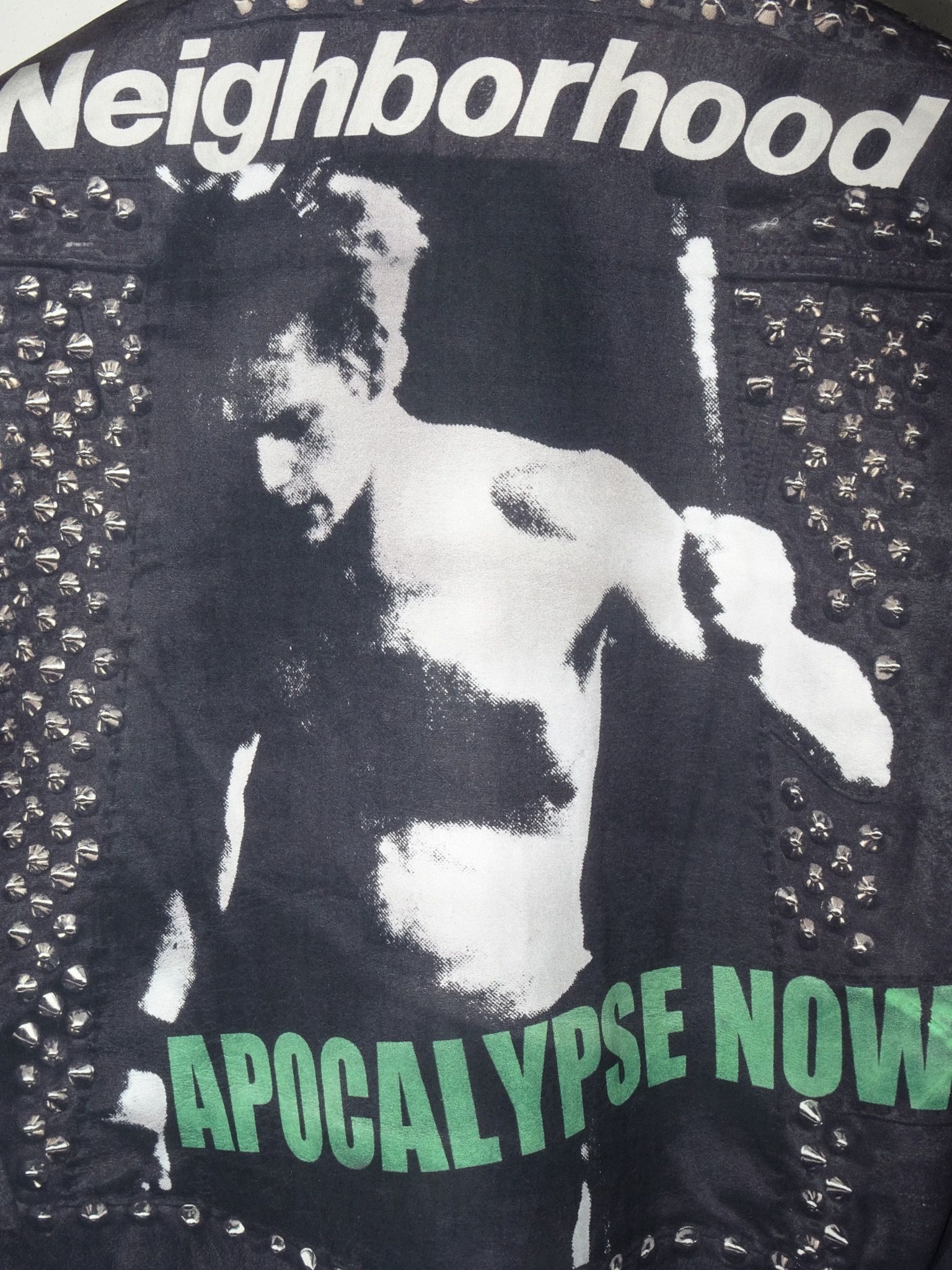

In the summer of 1988. That’s where I first saw this weird sticker that I didn’t understand. I was like, “what the fuck does that even say?”” It was Stussy. After that, I started to import things. As I mentioned before, there was a transition in the early/mid-1980s. For a few years there – let’s say before the release of “License to Ill” by The Beastie Boys – I was playing beat stuff, psychobilly, and I was really attracted to the whole Northern Soul skinhead moment. So the first thing I imported was Lonsdale.

I heard you once hauled a load of Lonsdale t-shirts back from England in your car.

Yeah, I drove to London to pick them up. At the time there wasn’t much communication – we didn’t even have fax machines. So the order was sent by mail, then I wired the money for the deposit. I only had 3 million Lire, so I took the car to Carnaby Street, where Lonsdale was, to pick up the order. I was afraid I would send the money and they wouldn’t send back the stuff, or they’d send me the wrong stuff.

Luca, there’s something I’m still focused on from that period. I might be wrong, but I think there’s something in it. As the extremely aware and intelligent person that you are –

Thank you.

You realized that there was a turning point, that an era was coming to an end – and that even the idea of decades was disappearing. There is a certain point of release that we are talking about that I place around 1977, which I link to the political movements of the time, when Michel Foucault and Deleuze and Guattari attended rallies against repression in Bologna. We still think in terms of decades – the 1980s, the 90s, the aughties, the 2010s – but it’s a mental division which in all probability expired this year. To look at a longer period, over the last 40 or 45 years, we have seen human life completely metamorphosize – to quote Harari – with great, unprecedented rapidity. You managed to intercept these changes as they happen – changes dictated by an idea of freedom. We entered an economic period in which social capital and communication took the place of material activity. How we decided to live and dress in that space – and inhabit sonar spaces – became palpably different from what we did in the past. It’s been a four-decade-long turnaround. The incredible thing is that while the 1960s and 1970s gave birth to dozens of musical genres, that pivot between the 1970s and 1980s is where we see the rise of all the genres that have dragged on into the present.

Sorry to interrupt, but in 1988 at the Ethos Mama Club [another cornerstone of electronic dance music at the end of the 20th century, as always near Rimini/Riccione], which came out of Aleph –

I went to both, unfortunately. That’s where I left my health.

It was the beginning of house music, and I was saying to myself, “How long will this last?” I was thinking two, three years – as you say, I was used to that rhythm of evolution! Every two years, there was a change, something new. Now 30 years later we are listening to the same things, in part.

Or derivations thereof.

Or derivations thereof, yes.

And the same thing, for this perspective, happens in the world of style. Because Emporio and Fiorucci, among others, unhooked the way we conceive of fashion. They spread it out. From that point on, street styles began to impose a code that has prevailed until the present day. In 1982, people in hip-hop wore tracksuits; now, we all do.

True.

I’d love to know if that change was something you anticipated, if you instinctively intercepted what has happened in the last three decades. Do you assign this nature of visionary to yourself?

Look, I can think back on many things – and I could give you a long list – that don’t make me feel like a visionary. The only thing I can say is that the field I went into turned out to be fertile ground for many years, something now recognized even by those who thought there was nothing there. To tell the truth, I don’t do a lot of research – I’m still going mostly on instinct. I see something that attracts me, and that’s where I go. It’s like a magnet. I don’t know how else to explain how I have approached music, art, or sportswear over the years. When I went to Los Angeles for the first time, I went to this sports/activewear retail fair – and in 1988 or 1989 in California, what that meant was a flip-flop and bikini fair. But at some point, all these brands were born, and suddenly when you went to see clothes, you would also see the Wu-Tang Clan rapping in another room and people skateboarding on the roof. What I felt was an energy that went beyond the beauty of a t-shirt. That was “the thing.”

It’s an animal thing; it’s pheromonal. You sniff the power of the other. You’re a diviner who is there looking, following rivers to fountains of youth.

Absolutely.

And this “thing” you describe has inevitably kept you young. Do you want to be like Elon and live to 150? Or you don’t give a shit?

No. Fuck, no.

How do you connect with 18 year-olds, how does contact with young people happen, now that this transformation of human experience has taken place?

Again, I look at people. I am talking about collaborators who work with me and near me, who can help me. The other thing I did, at least until the end of last century, was always make sure I was at the bleeding edge, feeling these and smelling things and seeing things up close and with my own eyes. I no longer see things from the frontline, but through the eyes of collaborators who help me, in their individual ways, to intercept these phenomena.

How do you choose them?

It’s not easy, because competence and professionalism aren’t enough. In sales, marketing, and digital, I choose people who seemed to have something more than that, something that makes me feel that they have the antennae to intercept what used to come naturally to me, but that is sometimes more difficult to catch now. Apart from travel and everything else, I’m 60 years old, as you noted. I’m here, trying to understand the moment. But when will there be a revolution worthy of note? That’s not what I’m seeing now, though I may be wrong.

What kind of revolution?

I’m speaking musically. I hear a lot of things I don’t like very much.

Are you concerned?

No, I’m not worried. But there are a few things used in music that are so violent that they cancel out everything else.

Such as?

The fucking vocoder, for one!

You mean Autotune?

Sure, whatever. I’ll tell you in a banal way: I like the underground. But there’s isn’t much happening underground. Not that’s influential. I’ve always used music – or bands, or DJs – to make events, to communicate something, right? I respect Kanye, I respect A$AP Rocky, I respect Travis Scott, but what I don’t like is this: either you are completely visible or not seen at all. It’s not like, there’s this, but there’s also that. You’re either there or you’re not.

You’re talking about the visibility mechanism of the digital sphere, which then somehow excludes the presence of an underground, of a laboratory where things happen. But there is also a micro-visibility, and lots of micro-niches under that that are perhaps harder to perceive. I think the issue instead, which brings me to the next question I wanted to ask you, is the fusion of cultures: where you were coming from an Italian context and immediately got immersed in an Anglo-American culture. Then you went to Japan, right? This instinctual M.O. took you to this metropolis that was pulsing at the time, and that was completely different from the other reference points.

Absolutely.

And there you intercepted other sensibilities – there was an element of streetwear, but also Kawakubo and Yamamoto. I’m also thinking of your choice to distribute Undercover, which is a brand influenced by the deconstruction and destruction that has infused Japanese culture since Hiroshima – and also this idea of supersonic youth mixed with a sense of searching for the unobtainable, for disappearance, for rarity, a trick that Supreme would co-opt years later. So where do you go looking for new sensibilities now? Do you have a sense of where the new avenues are?

I don’t have an answer for you, even though it’s something I think about often. I was attracted to Japan because, before streetwear, my great love is fashion, clothing, and Tokyo brands took American streetwear, which had a lot of content, and took it to new levels of quality. In music, I don’t like a four-hour set that starts at 110 bpm and goes to 130 – I like it to jump to 150, to 180 – and it’s the same thing with fashion. When I got the “yes” from Stussy in 1991, Italy had jeans stores and sporting goods stores but in my opinion none of them were good enough to carry that brand. So my first approach, because I saw this gap, was to go the fashion route, to take it to luxury boutiques – and it was only logical that they slammed the door in my face. But I had a vision of a store that would carry Yohji Yamamoto and Helmut Lang alongside Patagonia. And that’s exactly what’s happened today.

That’s what we’ve been calling “luxury streetwear” for a while now, right?

Meh – seeing streetwear as an end in itself, or a luxury retailer as an end in itself, is boring to me. It’s like the DJ set again – if they’re only playing house or only playing techno, it’s boring. The personality comes out in the assemblage of different worlds, in the combination of things that seem totally far away from each other. That’s where a DJ, or a store owner or buyer, has the opportunity to show their own vision of the thing, in a way that’s personal, intimate. Sure, it’s complicated. It’s easier to go up to the DJ booth and play house music for the whole set, or to open a store that just has Gucci and Saint Laurent inside.

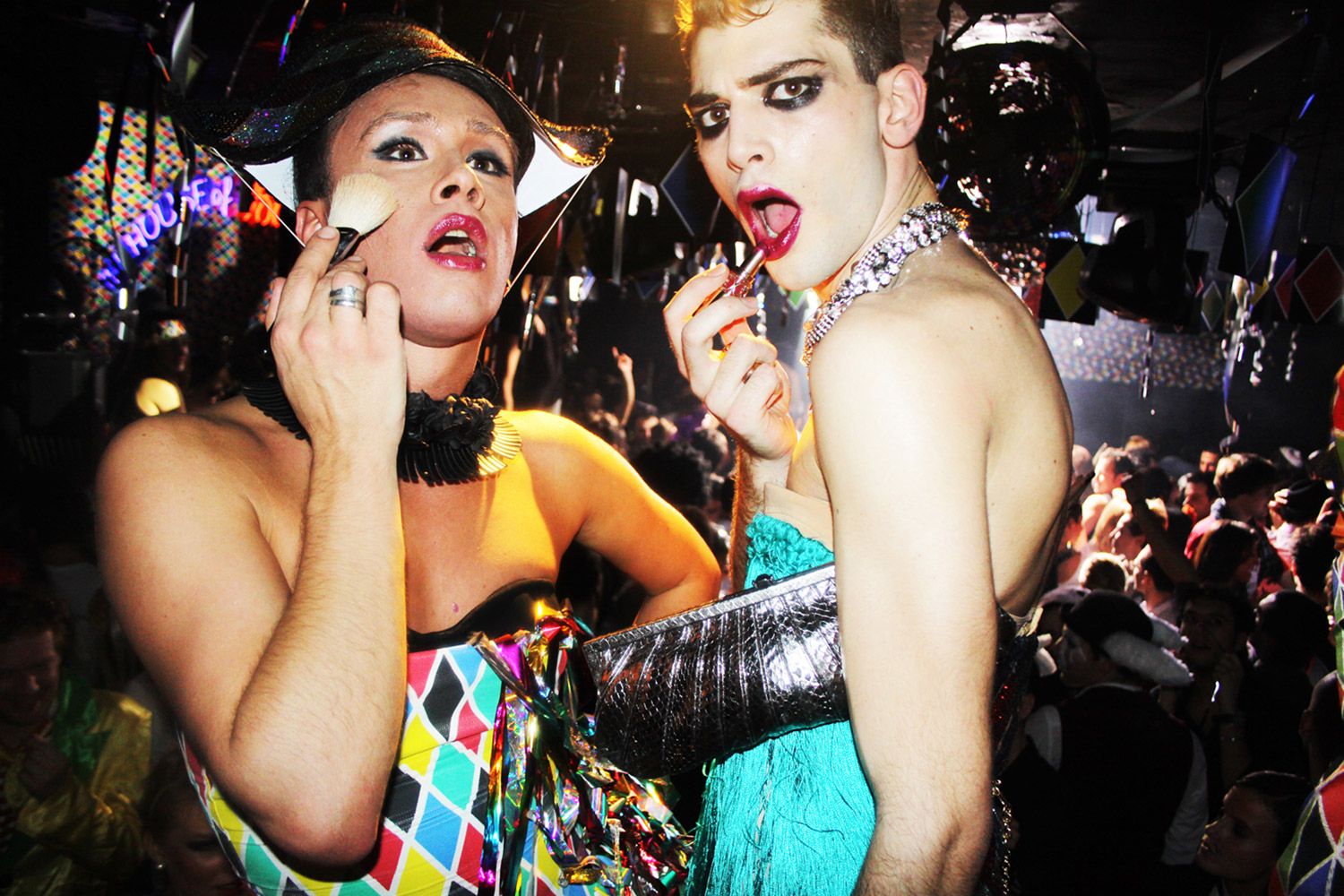

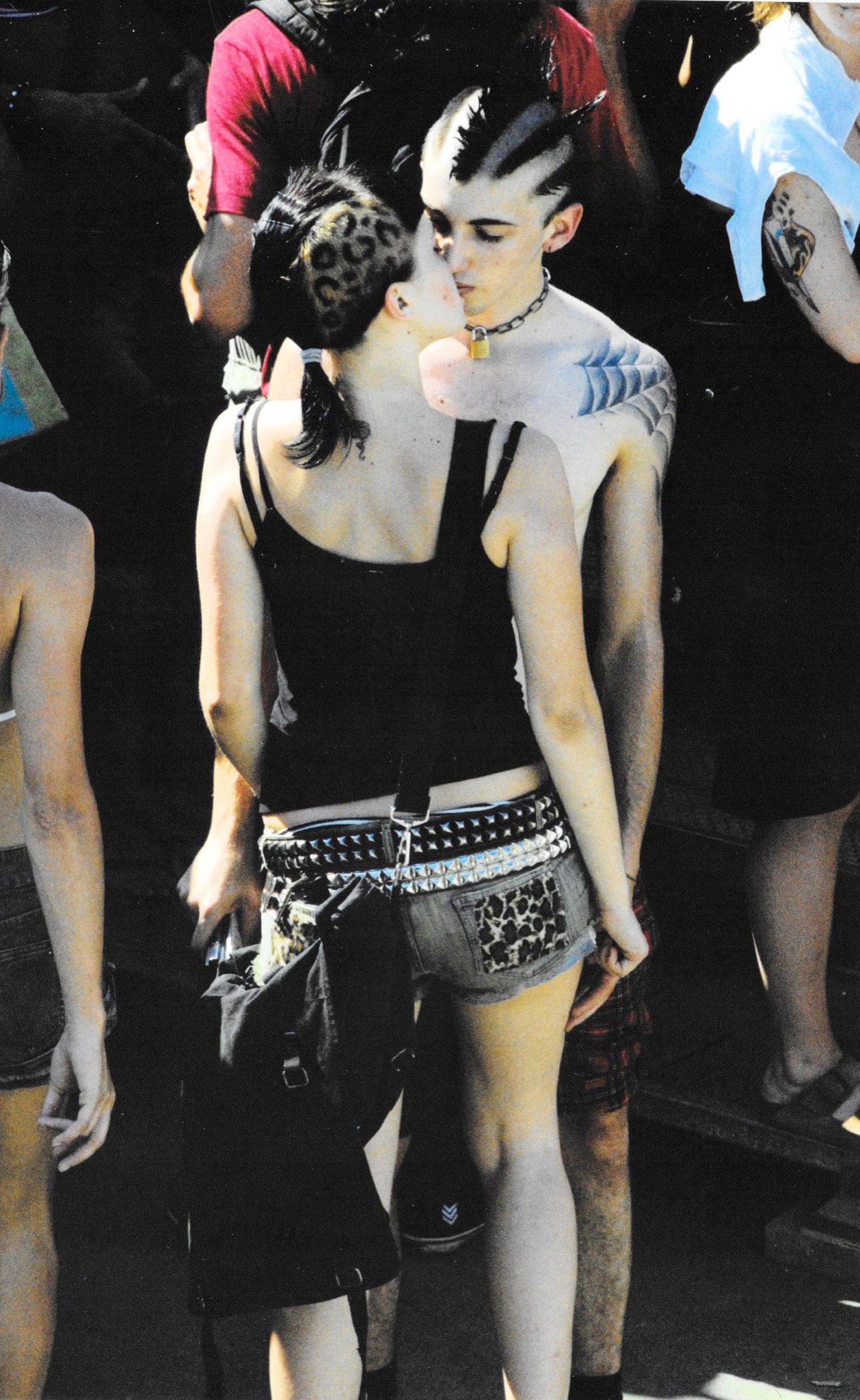

The actual intersection of nightlife, music, and fashion that you encountered in the late 1970s – and that informed our experience at Plastic, Aleph, and then Echoes in the 1980s and 1990s – offered a parallel world of other possible identities. It was also about sexuality, of course. Nightlife made possible a representation that revealed the truth. It provided a fundamental place where you could be what you wanted to be – and you needed the right clothes to occupy that stage, and to build that image into your everyday. It seems that you are somehow dealing with that relationship between a person and their identity, providing tools for transformation, for the various mutations of how one can occupy and be oneself within the urban fabric.

I can only totally agree.

We haven’t spoken much about the present day, but all these questions stem from my visit to the fantastic new site of the Slam Jam archive. This interview, in a way, is just the soundtrack for that presentation – which I should add also includes an actual 2.5 hour soundtrack comprised of vinyl from the archive itself. Contemplating these materials and the nostalgia they bring up for viewers made me wonder: is there a melancholia or a longing that has helped or motivated you in this journey?

Just the one! I live in constant melancholy and nostalgia. It accompanies me daily. But why do you ask?

Because that’s what I do.

Well, it’s certainly a question that hits home.

And it’s also at odds with what you do, right?

I’m not even bothered by it anymore – to tell you the truth, I actually enjoy it. When a situation is all happiness, I always want to leave. I like to feel some darkness, some melancholy. It’s something I’m not only used to, but that belongs to me. It’s a part of my soul.

The same soul that allows you to feel the energy of others! That’s why you have that magnet there to capture certain forces. The magnet is there: melancholia.

It’s there, huh?

It’s there.

(Many thanks to Achille Filipponi.)

Credits

- Interview: Carlo Antonelli

- Images: Courtesy of Archivio Slam Jam

- Special Thanks: Achille Filipponi