KERRY JAMES MARSHALL and the INVISIBLE MAN

|CHRIS DERCON

During a visit to Berlin, painter Kerry James Marshall speaks with future Volksbühne director Chris Dercon about his legendary self-portrait, the futility of abstraction, and the scandals surrounding Dana Schutz and Kelley Walker.

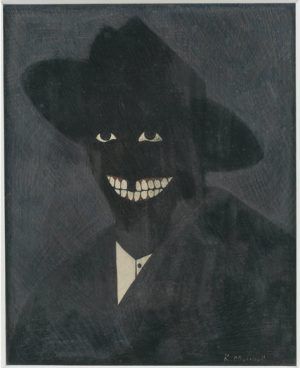

Since April of last year, Kerry James Marshall’s retrospective “Mastry” has been criss-crossing the United States — from premiering at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago to the Met Breuer in New York to where it is currently on exhibit at MOCA in Los Angeles. Aside from its critical acclaim, the exhibition has been a success in terms of Marshall’s own bluntly-stated aim: to populate the museum with more black figures. The artist’s figurative and often historical paintings began with a powerfully singular work, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self — a self-portrait in which the white surfaces of Marhsall’s eyes and teeth float on top of a largely black expanse. As an allusion to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, the artwork clearly defines the political and aesthetic notion that visibility — and its opposite, invisibility — is the strongest tool of power.

CHRIS DERCON: It all started with a very tiny self-portrait that was not larger than a book, and that painting was called A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self. You show this portrait with this amazing gap between the teeth, almost like a caricature. But what’s interesting is that you refer to Ralph Ellison’s book, Invisible Man, written in 1952. Why did you start with that single portrait as a kind of manifesto? And why did it have to be so tiny?

KERRY JAMES MARSHALL: It didn’t have to be so tiny. It just is. It’s probably that scale because I was doing a lot of collages, a lot of mixed media collages at that time that were about that size too. I had been interested in finding a way out of the aesthetic sensibility that collage allowed one to operate within. Which was in part, built around certain stances of chance. There was a point in which making works that had an element of chance ceased to be interesting to me, because it had lost the kind of challenging dimension that I was excited by. Ralph Ellison’s book presented me with an idea that struck me as being really meaningful and worth exploring, the way in which a thing could be two things at once — the condition of simultaneously being present and absent in the world, but not as a phenomenal condition. When HG Wells writes The Invisible Man, he physically becomes invisible, transparent to view. But in the case of Ellison’s character in the novel, it’s not a physical invisibility, it’s a psychological invisibility. That whole scene in the prologue of the book, where he has the encounter with the man on the street and he talks about the fact that, “I could cut his throat right now and he wouldn’t know what happened to him.” Because, essentially, he doesn’t see me. Even though we just bumped into each other here, this is an interaction we’re having because he is psychologically incapable of seeing who I am.

This is clearly also important for addressing the issue about the absence of the black man, or the black woman, in museums. The Louvre, the Nationalgalerie, Altes Museum – where we’ve only seen, so far at least, white men. You wanted to address this critical mass, which is absent. And it all started with that portrait.

Well, in anybody’s work, you reach a moment of crisis. You recognize that the direction you’re moving in, now may come to a modest kind of success, but it’s never going to get you to the thing that you’re really trying to access. The marketplace can be seductive, with the kind of money that flows through the art world. And a certain kind of market success can lead you to continue to do the same things over and over and over again, because you want to keep the money coming in, or you like to keep going to the parties that the galleries throw. All of that stuff is kind of nice. But you end up with the empty, hollow feeling about what you’re actually expending your energy on. I had arrived at a moment like that with those collages where I knew: with a certain amount of work, you sort of push the paper around, push a little paint around, build up a nice surface, get some nice colors on there. You can do that for a little while, and it will coalesce into something that you can more or less be satisfied with. That was no longer interesting to me. I needed something that gave me more challenge, something that was more precise. That image allowed me do it and allowed me to reconnect with my interest in particular, I would say Florentine, Italian Renaissance frescos. The thing that I liked about that work most, was that it seemed so cool and so calculated.

When I made that picture, I was trying to do something that used all of the devices they used in those paintings, but without having to make a picture that tried to look like those paintings. The way in which these absences present themselves, you encounter them in the books and you encounter them in museums, but if you go to art school – I went to art school even before the 1970s – you go in there and you take these life drawing classes and these painting classes, and just like in the museum and just like in the book, every single model they had in those classes was a white woman or a white man. That body is being the body that’s supposed to be in a painting. You sort of structure your expectations that way. It’s supposed to look like these ones that Michelangelo did, or Rafael did, or Titian did. It’s supposed to look like that because these models also look like that. Every time I would go into class, that’s who’s up there. You never get this sense that you are a part of any of that. And so, how do you move from that kind of expectation to constructing another paradigm? If that painting is a kind of manifesto, that’s when the manifesto starts to take shape and the beginning of a reset. From the moment from that painting, everything else I did was trying to create this model in which the black subject would be central, not peripheral to, the kinds of paintings I wanted to make. The condition of blackness in the paintings would be more absolute, not provisional.

You probably also wanted to take a stance in the debate. It was a very important debate in African American art in the 1950s and 60s — the debate about abstraction versus figuration. A lot of the African American painters in the 50s and 60s, they pleaded to paint abstractions in order to avoid this whole issue about figuration and blackness, because they considered it as no way out. Was this also a declaration in this sense? To say, “Listen guys, we have to try on. We have to do these figurations.”

When I graduated from high school in 1973, the question of whether abstract painting was more advanced than figurative representational painting had pretty much been exhausted and turned into a non-issue. And, for me, as a black man, what is it that I would be trying to achieve in the abandonment of the image? If you don’t achieve that equivalency — meaning, if the presence of the black figure in the painting is the exception to the rule and not a part of the general rule — then you’ve arrived nowhere. If you want to achieve a certain level of equality, for me, that means that you are able to operate independently without fear of the consequences of having it done. If what art history is structured around is privileged artists who seem to have contributed something to the practice of making pictures or paintings that had an impact on how other artists who followed you were able to think about what they were able to do, well, then then that’s my goal there. My thing was that I wanted to have images like those in the museum. A single encounter with an image like that has the capacity to change your expectation of what you’re likely to see when you go to the museum the next time. It is no longer the exception to the rule. It is a commonplace.

I think a remarkable line in one of your writings, it’s in the text about Emmett Till, you write, “David Hammons always meant more to me than Bruce Nauman. Just because …” Dot dot dot. Just because what?

Well, just because. [Laughs]

But just because of what?

It’s proximity. When I encountered real artists in the flesh, one of those artists that I could encounter in the flesh was David Hammons. Long before I was ever going to meet Bruce Nauman. That matters. When Kellie Jones curated the show called “Now Dig This!” — about black artists in LA between 1960 and 1980 — there was a roundtable discussion about that specific exhibition. John Baldessari was a participant in that conversation and this thing that he said sort of makes the “dot dot dot” comprehensible. He starts in his remarks: “All the artists were in Venice. David Hammons was isolated somewhere out there in South Central LA.” I was in South Central LA. so David Hammons was not isolated in South Central, he was there with me. My perception was not that all the artists were in Venice, because all of them were not. Your world view is the circle of people you move around with, and so what Baldessari’s comment highlights is that the art world is as narrow as any other kind of domain you would find anywhere else. The artists that John Baldessari was hanging out with were not talking about the same things David Hammons was talking about. They were not trying to do the same thing David Hammons was doing. The things that David Hammons did seemed pretty interesting to me.

When we talk about African American art today, there seems to be a canon established by certain museums. Of course, we mention David Hammons, we mention Kerry James Marshall, and then we have artists like Kara Walker, or Fred Wilson. Is there now a certain group where you say: “I, Kerry James Marshall, I belong to that group. These are my folks. They’re addressing the same kind of thing as I want to address, but in different ways.”

Yeah, but I’m older than them. I know a lot of people, and we do feel like we have a certain affinity for each other because we’re interested in some of the same things. We have some of the same kinds of conversations, you know. This is the kind of thing that goes back to some of the differences between the Black Liberation Struggle and the Civil Rights Movement. You have a Black Liberation Struggle, which was overtly committed to an idea of self-determination, and a Civil Rights Movement that was overly invested in an idea of integration. Self-determination requires no compromise. You establish a structure that allows you to get what you want, independent of what anybody thinks you should have. That’s what self-determination means. So what we don’t have as a group, a culture, is a certain kind of self-determination. We don’t have an independent economic apparatus that generates the kind of money that museums, art galleries, collectors have that helps make the art world run. We don’t have control of an apparatus that can generate the same kind of money and the resources that already exist in what people call the mainstream. We do not have that.

But you have Beyoncé, you have Kanye West, you have a kind of commercial African American culture.

That’s not it.

Ok, so what is it then?

That’s not it.

I mean, Raoul Peck was saying that when Beyonce decided to put herself on a stage and do the black panther fist movement just in television time, that doesn’t mean anything to him.

Yeah, but on the other side of it, there’s a difference between earning a lot of money and creating capital. Those are two different things.

So, Beyoncé is doing what?

She earns a good living. She does not create capital.

So, we agree.

Capital is the foundation of an economy. And more people can tap into the economy that generates capital than can get benefit from your generosity if you earn a lot of money and give a lot to charity. Those are not the same things.

Then we come to the last topic, and it’s unavoidable. When Kelley Walker put up his art works at CAM in St. Louis, the black community of Saint Louis protested. The curator who put up the show, he resigned. The second issue is of course involving Dana Schutz, because when she painted Emmet Till, Kara Walker had to take her defence against other artists like Hannah black and African American activists in New York. Of course this topic is much broader, it’s all about cultural appropriation. But what is your view? Can you give us advice on how to look at these things in different ways?

No. I mean, I don’t know what kind of impact those things would have on anybody else but me. I don’t have a prescription that would be a kind of prophylactic against the backlash that Dana Schutz could take. She couldn’t take a pill that would make her immune from backlash with the production of an image like that. I mean, you do it and you have to take it as it comes. Artworks are not benign, they are not immune to this kind of reaction, and the museum is not a completely hermetic protected barrier. Historically, it is not out of the ordinary for artworks to be destroyed — and I’m not saying that her work needs to be destroyed, but it’s not out of the ordinary for artworks to be destroyed or to be damaged when one regime comes into control. They don’t just keep the stuff the people had there before.

Ok, but what you’re saying is that Kelley Walker, Dana Schutz, and the curators putting up the works should have known what they’re getting into.

Well, I would say you should have some idea. If you don’t, what does that say? That either, you are painfully naive about what’s going on in the world. Or, there’s a kind of arrogant sort of disregard for the impact you might have on other people. Because nothing happens in a vacuum. If you think about the historical, the moment, in which the things that we make become publicly available, they create a climate in which the reaction you get from it is kind of predictable. And depending on the kind of responsibility you’re willing to take for the image you make, if you think you’re bad enough, do it. Do whatever it is you want to do. And if people come at you, don’t whine about it.

Kerry James Marshall visited Berlin as a Max Beckmann Distinguished Visitor of the American Academy. For more from this conversation, click here.

Credits

- Interview: CHRIS DERCON