“AMERICA IS ME”: The Life and Times of GORDON PARKS

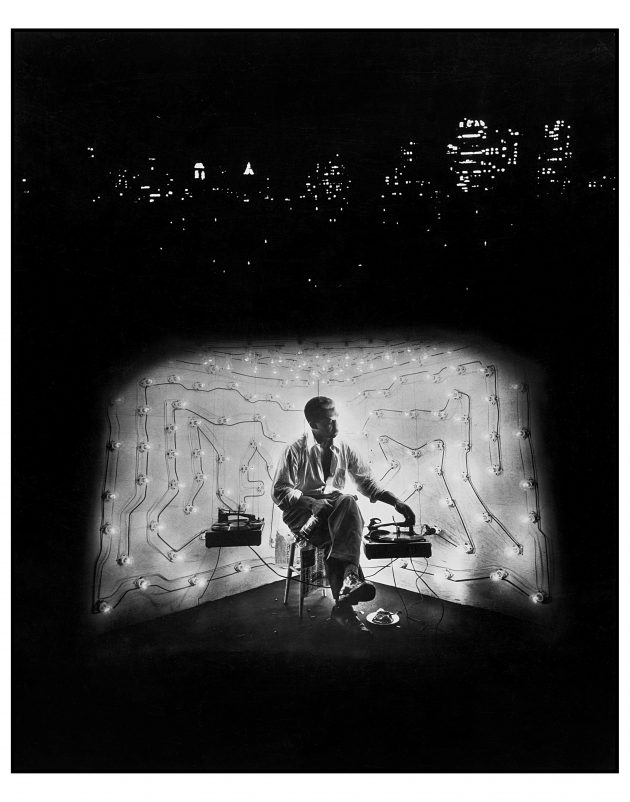

In 1952, Gordon Parks collaborated with author Ralph Ellison on a photo essay for Life Magazine titled “A Man Becomes Invisible,” restaging scenes from Ellison’s novel Invisible Man. Published only a few months prior, it tells the story of an unnamed African-American protagonist whose skin color renders him invisible to the eyes of people he calls “dreamers.” Its narrator elaborates: “I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination – indeed, everything and anything except me.” Employing elements of surrealism, Ellison succinctly describes his very real experience of US American racism. But his stunning novel blurs the border between fiction and reality further, since describing the invisibility of an experience carries the promise of increased visibility.

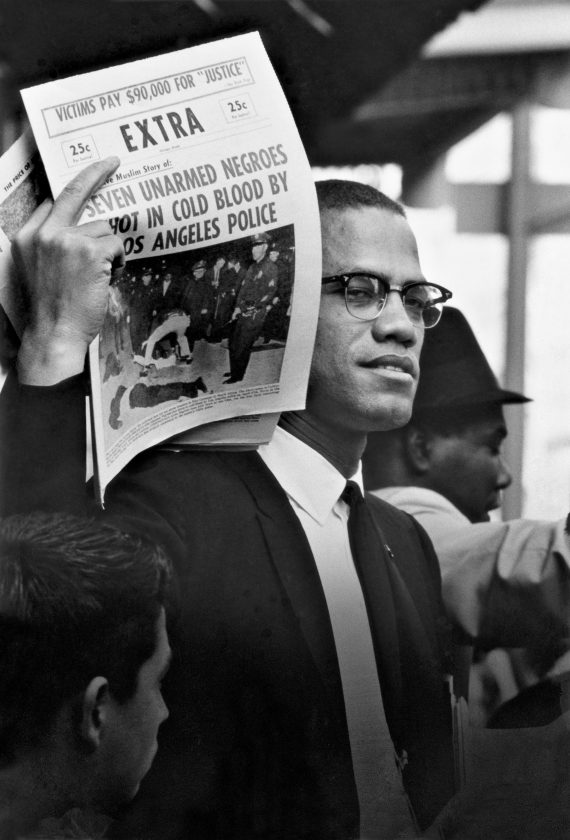

Parks’s work as a photographer and writer for Life carried a similar promise. At the time, he had already portrayed the lives of young gang members in Harlem. He would later go on to document the social and racial inequality of American life further through a gut-wrenching reportage centered around an impoverished black family in the district. “I picked up a camera because it was my choice of weapons against what I hated most about the universe: racism, intolerance, poverty,” Parks said. Simultaneously, he also shot glamorous fashion editorials and piercing portraits of cultural icons from Ingrid Bergman to Duke Ellington to Muhammad Ali. He traveled back to Kansas to poetically capture the setting of his upbringing, which eventually resulted in him directing The Learning Tree, a movie based on his book about his childhood of the same name, and the first Hollywood movie by a black director. He shot a groundbreaking editorial on the Black Muslim community in Chicago and New York, and vividly documented the civil rights movement’s march on Washington. The immense versatility of Parks’s work is highlighted in I Am You, the monograph of his work published by Steidl, The Gordon Parks Foundation and C/O Berlin on the occasion of the latter institution’s retrospective of the artist.

Its dense 285 pages convey not only the multiplicity of scenes Parks photographed, but the consistency of his work too. Whether his subject was a film star, Malcolm X, or a young boy at a Kansas carnival, Parks was able to focus on the person he was to portray beyond the implications of their surroundings and accompanying projections. I Am You presents multitudes of Americas that existed parallel to each other or at times blended into one another between the 1940s and 80s. It sets them into relation with one another. Parks, who also directed Shaft and was among the co-founders of Essence Magazine, especially showed black Americans in previously unseen diversity. He captured their collective struggle with systemic oppression. And he also portrayed the leaders of the civil rights movements, as well as everyday moments of beauty and freedom. Rather than showing his subjects as faceless embodiments of their discrimination, Parks allowed them to exist as individual subjects with shared narratives. Sometimes even heroes, as he told Roger Ebert on the reception of Shaft in 1972: “Suddenly, I was the perpetrator of a hero. Ghetto kids were coming downtown to see their hero, Shaft, and here was a black man on the screen they didn’t have to be ashamed of. Here they had a chance to spend their $3 on something they wanted to see. We need movies about the history of our people, yes, but we need heroic fantasies about our people, too. We all need a little James Bond now and then.”

In his portraiture of social exclusion, Parks’s subjectivity as a black reporter is also always part of the image, lending visibility not only to his subjects, but also his own perspective whose vulnerability is caused by the same structures that threatened the livelihoods of many of the people he portrayed. Now, visibility does not guarantee equality or even safety. And multidimensional portrayals of people of color remain very rare in mainstream culture. This year, Issa Rae’s excellent HBO comedy series Insecure has been lauded for its authentic portrayal of black female friendship. Barry Jenkin’s outstanding independent movie Moonlight told the story of Chiron, a gay black boy growing up in Miami. Both Moonlight and Insecure’s storytelling, photography, casting and soundtrack choices are exceptional. As long as the identity positions of their protagonists further their exceptionality, Parks’s striking glimpses into the not-so-distant past are of immense importance. One that exceeds the historical relevance of his oeuvre. Because as long as one is invisible, seeing your experience and its multidimensionality reflected in cultural products is of immeasurable value. In the words of Parks himself (“A Harlem Family,” Life, March 8, 1968):

“What I want. What I am. What you force me to be is what you are. For I am you, staring back from a mirror of poverty and despair, of revolt and freedom. Look at me and know that to destroy me is to destroy yourself. You are weary of the long hot summers. I am tired of the long hungered winters. We are not so far apart as it might seem. There is something about both of us that goes deeper than blood or black and white. It is our common search for a better life, a better world. I march now over the same ground you once marched. I fight for the same things you still fight for. My children’s needs are the same as your children’s. I too am America. America is me. It gave me the only life I know–so I must share in its survival. Look at me. Listen to me. Try to understand my struggle against your racism. There is yet a chance for us to live in the peace beneath these restless skies.”