If You Are a Cop You do Not Have Permission to Cook This: Chinese Protest Recipes with CLARENCE KWAN

|Octavia Bürgel

Chinese Protest Recipes, a new zine by Clarence Kwan, announces three goals in bold typeface on its fourth page:

1. SUPPORT BLACK LIVES MATTER

2. RAISE AWARENESS ABOUT RACISM AND WHITE SUPREMACY

3.RESIST THROUGH CHINESE FOOD

A particularly concentrated period of anti-Black violence rippled across the United States earlier this year, a confirmation of the dark prophecy indicated by the nation’s disregard for the disproportionally Black and Brown victims of this pandemic. We shared, marched, rioted, and donated; we read, cried, taught, wrote, and pored over the news. But many of us, people of color in diasporas worldwide, are still grappling with the devastation. Chinese Protest Recipes comes at a time when Asian communities in the West are suffering under racist aggression newly emboldened by Covid-19, and the deliberate misinformation circulated about its origins. “I realized I had a lot to say,” Kwan tells me during our correspondence.

Having volunteered on the ground in Toronto’s Chinatown, cooking and distributing free meals to community residents in need, the Chinese-Canadian cook took to his Instagram (@thegodofcookery) to begin sharing messages of solidarity between Black and Chinese communities after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. “Whether you are conscious about it or not, you are making a political act and actively upholding white supremacy three times a day when you choose what to eat,” he wrote on Instagram. Calling for a decolonized approach to cuisine, Kwan urges his audience to look beyond what has been validated by Eurocentric accolades or institutions – and toward an exchange of cultural knowledge produced and perfected with patience, practice, and love.

+DOWNLOAD CHINESE PROTEST RECIPES FOR FREE BELOW

I’ve been happy to see more conversation and mobilization around food justice as a result of the uprisings in the States. Ghetto Gastro has been using its Food Is A Weapon campaign as one way of centering access to food within discussions of racial equality, and many of my peers and friends around New York and in other cities have been initiating and maintaining community fridges to supply free, fresh produce to those who may not otherwise have that access. Chinese Protest Recipes is another amazing effort to encourage solidarity between communities of color through the language of food. What jumps out to you about the way North Americans relate to food?

First of all, the Ghetto Gastro crew is awesome. I really respect how they fight through food. I’m based in Toronto, but from what I’ve seen, I find Americans eat and relate to food similarly to the way they live – within their comfort zones. It feels very binary. People eat food that feels safe, and avoid the unfamiliar. Discovering other cultures through food still remains a novelty to most, and that’s reflected in the way people live and interact with each other, which is to say, it’s still very divided. Many people are still choosing big corporations to feed them overly sanitized food, rather than a neighborhood mom and pop. Unadventurous, gentrified, white-washed eating habits have led to a breakdown in the way we interact with one another, and in how we support our communities.

What, if anything, have you found to be missing from the food justice conversation?

In terms of food justice, I think the discussions are just beginning. People are starting to understand the concept of food insecurity. This pandemic has raised massive concerns about poverty and homelessness, and about the fact that many people still struggle to eat well on a regular basis. Racism in food requires a deeper level of seeing. The idea that erasure, colonialism, and white supremacy are alive and well in the food world is still a very new concept to many people. What is missing is a baseline level of awareness – that certain forces uphold and keep the status quo going, both in food and in other sectors. Action needs to happen, but it can’t occur without a re-examination of the food system that we live within.

“It’s written through my lens as a Chinese-Canadian person working at a New York-based, Black-led social impact agency, and cooking part-time in a Chinese BBQ restaurant during a Sinophobic pandemic, in the middle of the biggest racial uprising in modern history.”

The act of cooking is deeply entwined with notions of care and love. In this time when gathering together is still quite restricted, how do you hope that people will engage, share, or actualize the notions of refusal inherent to the recipes?

Even in a pandemic, I think you can still resist through food. You don’t have to gather in order to do so. Food is culture, and once you understand that concept, you can start investigating your assumptions and relationship with food. Question what you cook and eat every day. Is it diverse? Is it the same old continental menu every meal? Do you consider eating ethnic food “adventurous”? Do you ever get groceries at a BIPOC-owned store? These are questions I want people to ask themselves. Your relationship to food is often a reflection of your relationship to other people and communities. Challenge your palette, challenge your assumptions, and challenge your comfort zones.

Do any of the recipes you included in the zine carry legacies of protest within Chinese history?

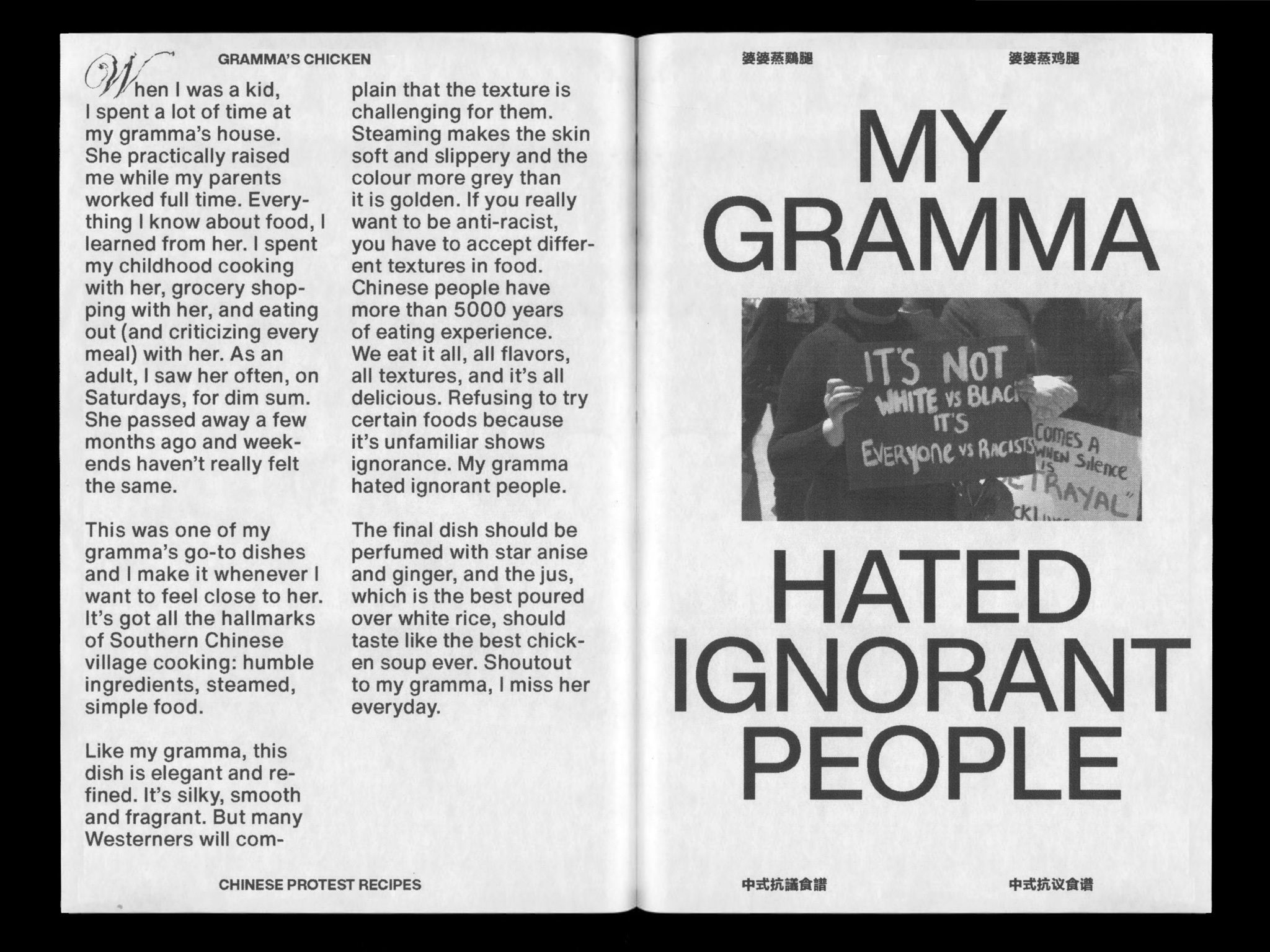

I didn’t grow up in China, so I’m not sure if these recipes are particularly “protest-y” over there. But as a Chinese person who grew up in a Western society under a white gaze, I think all Chinese food is inherently protest food. Our food, just like many BIPOC cuisines, has been ridiculed, mocked, insulted, and literally spat on. I believe it is one of the grandest cuisines in the world, yet it remains in the gutter of white society, even though it’s been in North America for nearly 170 years.

I think eating food from your heritage, boldly and unapologetically, is a form of protest that you can participate in three times a day. BIPOC shouldn’t let white shame change their eating habits. Be proud of who you are and where you came from. When I was a kid, I was embarrassed of my native food. Somewhere along the line I realized I will never let that happen to me ever again. I eat BIPOC food every day as a middle finger to how the white world “wants” us to eat.

“Challenge your palette, challenge your assumptions, and challenge your comfort zones.”

There is a long and radical legacy baked into the zine format – the affordability of materials, their DIY nature, the anti-authoritarian spirit, the capacity for quick dissemination. They have been mobilized to speak to all manner of political struggles over the decades. Have you always made zines?

I have made zines before! They’re so raw and personal. One of my old food zines made it into a MoMA exhibit as part of The Newsstand project a few years back – shoutout to Lele Savari! I’ve always been inspired by that aesthetic; I grew up admiring Raymond Pettibon, Tom of Finland, and early punk zines. I’ve always been inspired by Chinese restaurant menus – how they are always raw, honest, and have accidentally amazing design.

I worked with Ron Tau of Meat Studios to design this project. The message of the zine is very direct, so we avoided anything overly designed and tried to let the message be straightforward. It was definitely inspired by the legacy of classic protest design – no BS; black and white; no affectation whatsoever. It hits you like a bat – you can’t walk away from it.

The zine does a great job of addressing the sometimes tense relationship between Black and Asian communities in North America. You call out specific anti-Black attitudes within Asian communities while also highlighting the severity of the racism leveraged toward Asian populations in the West – especially in the Covid era. Did you have a particular group in mind as your primary audience?

I didn’t have a specific audience in mind when I created Chinese Protest Recipes. I wrote it from my personal experience as an outlet because, to be honest, I needed to get some things off my chest. It’s written through my lens as a Chinese-Canadian person working at a New York-based, Black-led social impact agency, and cooking part-time in a Chinese BBQ restaurant during a Sinophobic pandemic, in the middle of the biggest racial uprising in modern history. I realized I had a lot to say.

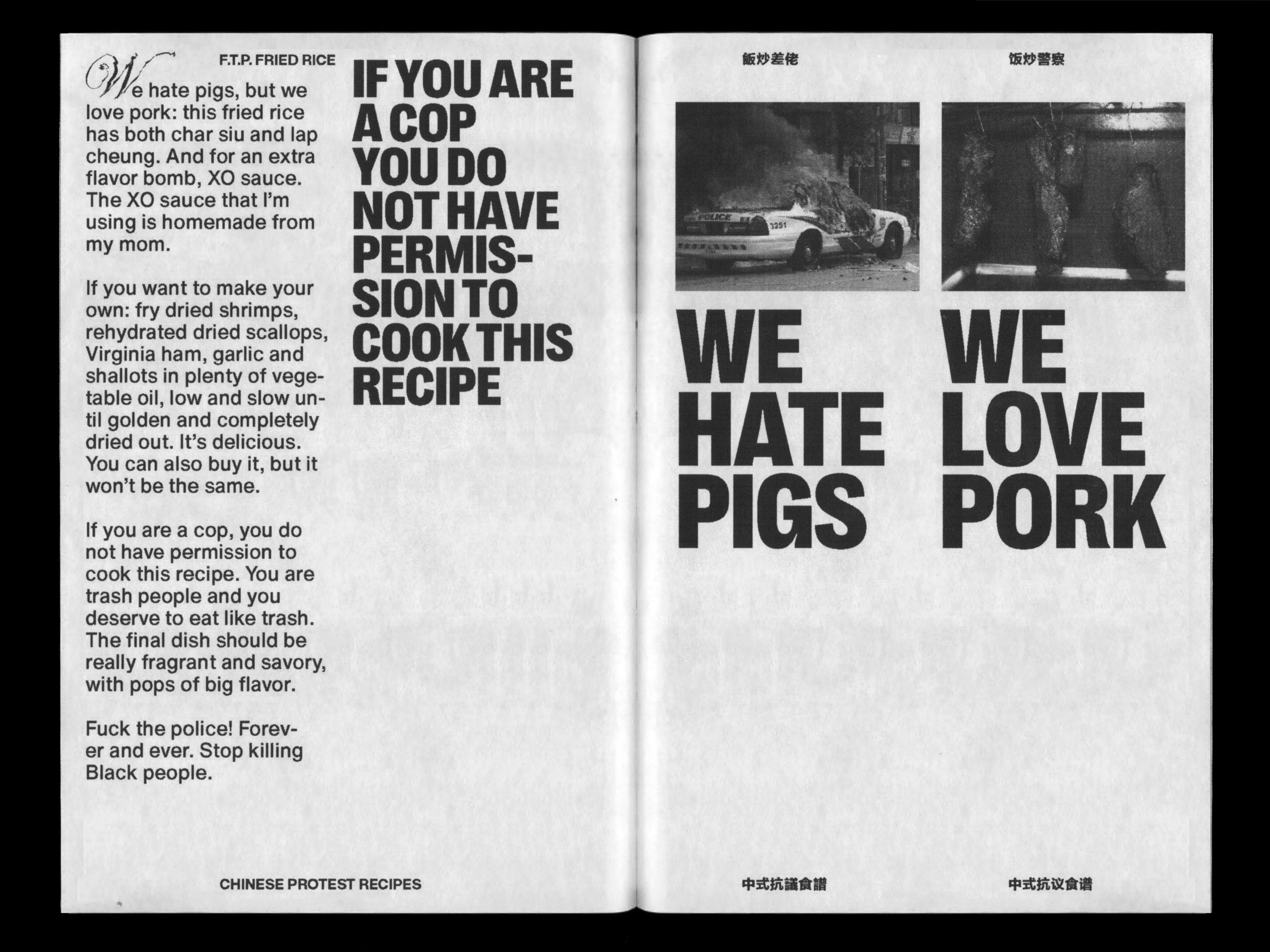

There is no one audience; the message is different to different people. Sometimes I’m asking Asians to pull up for Black people, even when we are hurting. Other times I’m asking white people to break their habits. Sometimes I just put cops on blast. It’s a really complicated time right now, so I feel like just about everyone has something to learn and unlearn, including myself.

Did prior solidarity movements between communities of color inspire or affect the way you approached this conversation?

I grew up seeing all the iconic images of Yellow Peril supporting Black Power from the 1960s. Seeing all the POC communities pull up for Black people during these protests was really inspiring. Seeing signs like “Palestine supports Black Lives Matter” gave me goosebumps, because any person of color can relate to the idea of struggle. There’s a huge feeling of solidarity that sinks in. At the same time, I will never know what the Black experience is like. So I wanted to create something that helped to raise awareness and center the issues at hand, but to do it through a platform that was authentic to me, which was Chinese food.

Speaking of solidarity, when the initial uprisings began in the US in late May, I saw a lot of young people on social media exchanging protective protest strategies and circulating vital information that came directly from student protesters in Hong Kong. That hasn’t seemed as prevalent in the intervening months, but it feels like a critical time to support and maintain that exchange of knowledge. In what ways can we continue to encourage solidarity across these global movements?

Oppression is oppression, no matter where you are in the world. We’ve seen that in Hong Kong over the past few years. Hong Kong and Cantonese culture are under threat. At the same time, here, in North America, Black people have been fighting oppression for four centuries. There are certainly parallels, even though the level of oppression is not comparable. But what we have learned, over the many uprisings we have witnessed, is that there is power in numbers, that speaking out, using our voices, and standing up for our rights, no matter where we are, is vital. If you value freedom, you need to stand up against injustice and show solidarity.

Strategically, I think we’ve witnessed how data and social media can be weaponized – for good and for bad. We are in a new era of protesting where we can organize and communicate online. Use your platforms, no matter how tiny. It will make a difference. That’s what I did. There is a massive learning and unlearning going on right now; we just need enough people to wake up and make it a part of their lives, on- and offline. History has taught us that any regime can be toppled. We have more tools than ever before. It’s now time to stand in solidarity with BLM and dismantle the system, because, as Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panthers, wrote, “the power of the oppressor rests upon the submission of the people.”

DOWNLOAD CHINESE PROTEST RECIPES HERE

Credits

- Text: Octavia Bürgel