In conversation with EBONY L. HAYNES and NIKITA GALE

|Katja Horvat

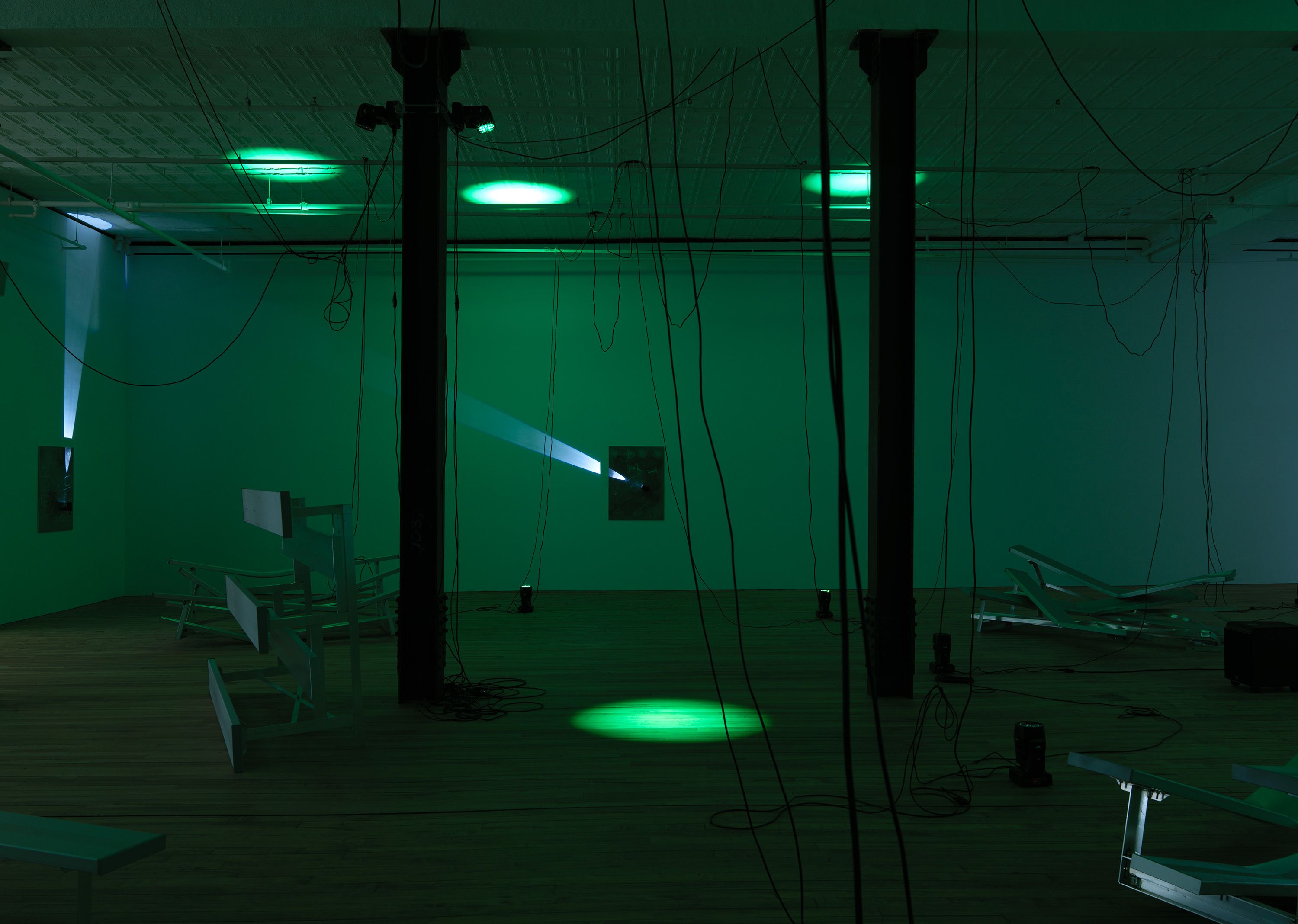

52 Walker is a David Zwirner Gallery offshoot that opened in Tribeca in October 2021 with an inaugural show by Kandis Williams. Directed by writer and curator Ebony L. Haynes, the space was conceived to bring a critical and curatorial approach to the traditionally commercial blue-chip platform, emphasizing research and dialogue. Haynes’ slowed-down program, complimented by a robust series of talks and live engagements, presents just four shows per year, expanding and nuancing artists’ scope engagement with viewers. 52 Walker’s second show, opened in early 2022, was Nikita Gale’s “END OF SUBJECT,” the result of an intimate conceptual conversation between Haynes and the artist, centered on the history and politics of sound.

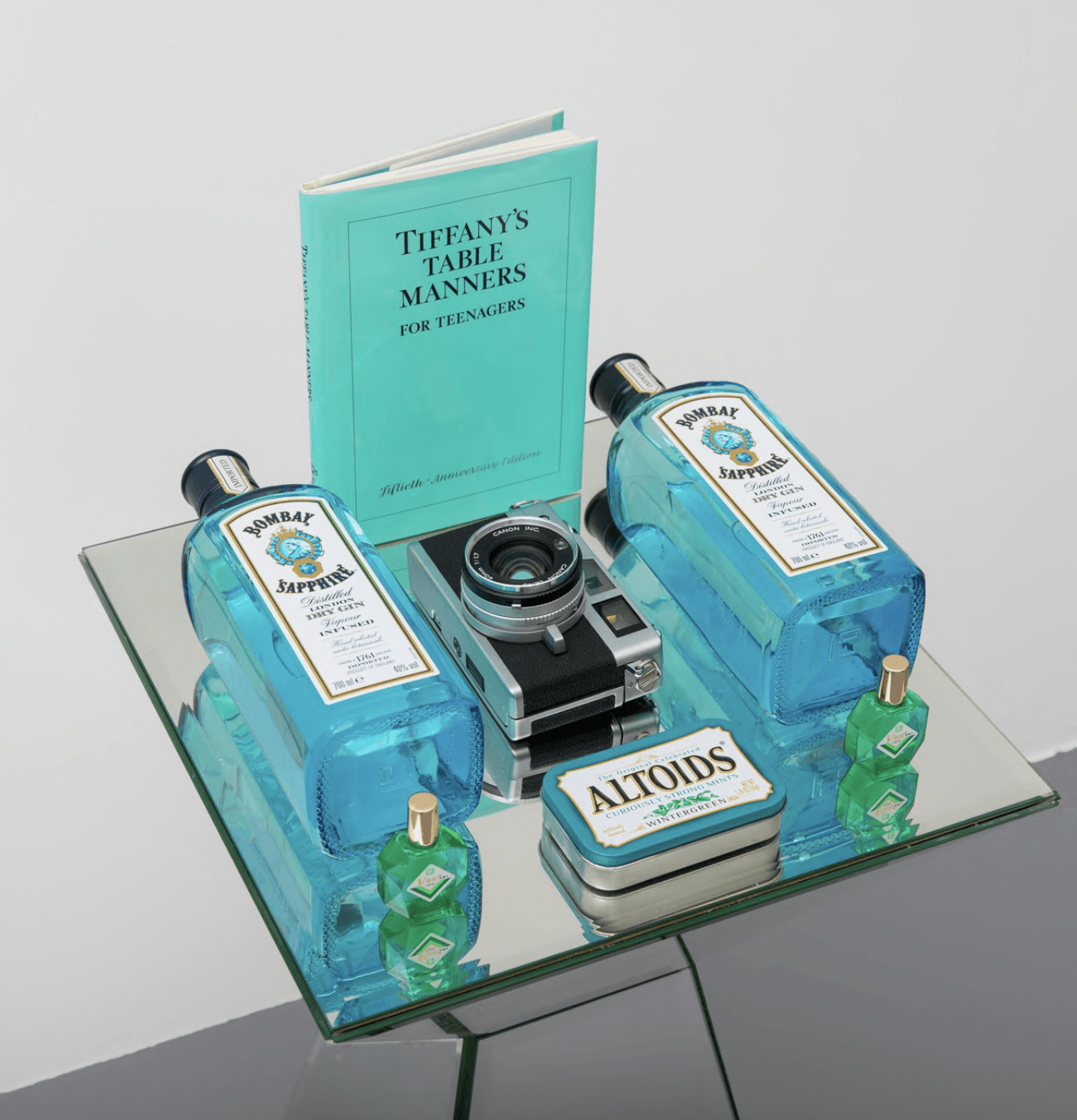

Born in Alaska, educated at Yale, and currently based in Los Angeles, Nikita Gale is interested in our understanding of memory, identity, and relationships – including the relationship between image, sound, and text both written and spoken. “END OF SUBJECT” explored these connections by marrying the audio-visual with the physical in an immersive, multi-sensory installation that considered objects as messengers and artworks as speech. As means of expression of an array of sentiments – moral, political, or purely emotional – what these physical creations communicate, Gale’s practice tells us, is contingent on context and perception. Viewers bring personal biases to their understanding of each work’s message, and the artist and curator provide a narrative onto which they can subjectively project. Gale’s work confronts this interplay with a study of memory and its synthesis as verbal, visual, aural, or tactile experience. At 52 Walker, “END OF SUBJECT” asked: how, precisely, do power relations and the politics of visibility influence the perception of an artwork?

In the second installment of her series of conversations for 032c, Katja Horvat speaks to Haynes and Gale about origins and pathways to art – and whether or not there is a wrong way to understand it.

Katja Horvat: Why do you do what you do?

Nikita Gale: Honestly, I often do things because I am not good at them. I like doing things I am good at, but I also like doing things I am not good at.

Ebony L. Haynes: Well, that is why you are good at what you do! Because you figure out ways how to do it. All your work is about figuring something out.

NG: I guess that is true. What about you? Do you do what you do because you are so good at it?

ELH: Actually, it's the same as you — because I am not good at it. I always felt not good at it, in a sense that I didn’t formally study art history. I had a whole other life before working in art. And until I interned at the gallery, I had never even physically stepped inside one.

KH: What were some of the weirdest jobs you both had back in the day?

NG: When I was an undergrad I took a semester off, and I worked in food service at Jillian’s, which is kind of like Dave & Busters. It was so intense, probably one of the most stressful jobs I ever had, and I was not good at it, ever! [Laughs]

I spilled food and drinks on people a couple of times. One time I spilled an entire tray of Coca-Cola’s over a mom at a kids’ birthday party.

ELH: I don't know if I should use this outlet to divulge all the weird jobs I’ve had. But, one of the fun jobs I had, which is totally outside of the field I ended up in, is what’s called a “mutual” at a horse racetrack. It was during college, and my job was to take the bets. I got really good at it too. It's like a coding system you need to figure out. I would also gamble all the time, but then again, I love any type of gambling, still to this day. I love dice, lottery, scratch cards, roulette. The only thing is, I don't bet big enough to win big.

KH: Let's backtrack for a bit. What did you both study? Nikita you are an anthropologist by education, correct?

NG: Yes, I studied Archaeology and Anthropology.

ELH: Me too, Anthropology.

KH: Me too. Cultural Anthropology and Ethnology.

NG: Cool! [Laughs]

ELH: And here we are: The Anthro club.

KH: I studied in Slovenia, and, how do I say this nicely, my studies were pretty outdated and post-university career options were minimal. They were mostly overly institutionalized, underpaid, and unappreciated jobs. How was that in the States? Was it more diverse in terms of career prospects or the same situation?

NG: In my studies I focused more on archaeology. I remember thinking during that time about what kind of career I could have. It was very clear that it would require way more outside resources and knowledge if I didn't want to take an expected field job or end up working in real estate, as they hire archaeologists in case, they come across some indigenous cultural artefacts.

ELH: I studied Cultural Anthropology and African Studies. I always thought I would work in some public sphere. I mean, I don't even know what that means apart from governmental stuff, public spaces, playgrounds, grant money, or maybe public programs.

But Nikita, let me ask you a question: When I look at your practice and how you do things, you are an archaeologist in your work as an artist. It's not like you are trying to dig up bones, but the idea from an overarching lens of ruins and history is very much there — looking at the foundation of the ruin, how we categorize and value ruins and the systems that create them.

NG: I agree. Going into archaeology, it was all always so speculative. If you found something that no one knew existed before, the whole narrative changed of what was once known. This element of speculation gives me more confidence in agreeing with you that my work is archaeological.

KH: What did you want to be growing up?

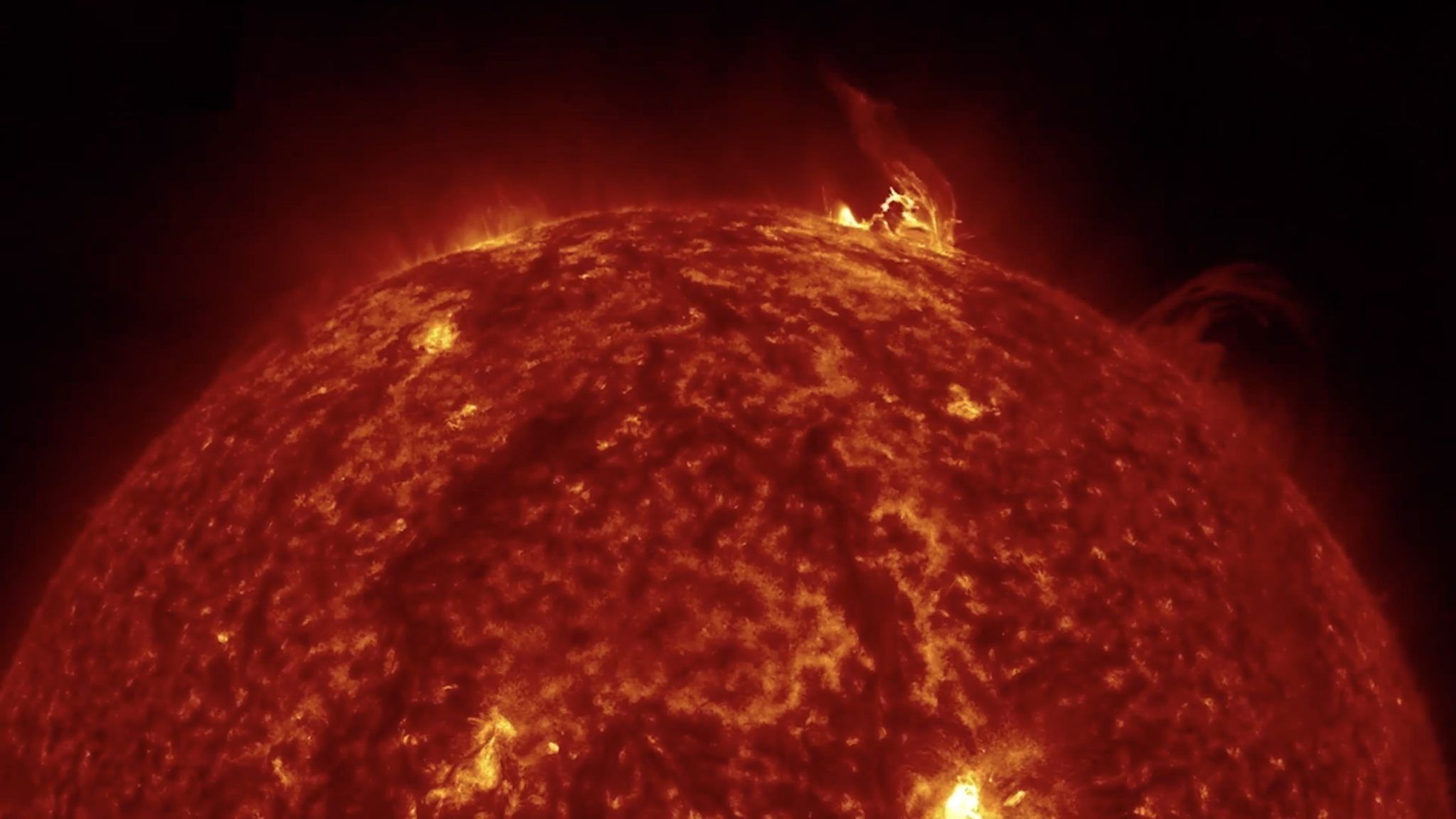

ELH: Let me try to guess for Nikita — I would think something NASA related. Not necessarily an astronaut but something to do with space. I don't know what I based this on, as Nikita mentioned nothing space-like to me, but it feels like it could be a thing?

NG: This is funny, because when I think of you, I would think you could be a pilot or some other aeronautical thing. [Laughs] Is it too late for us to do it?

ELH: It's never too late! But what did you actually want to be?

NG: When I was a kid, I wanted to be a truck driver. But then I watched Jurassic Park, and I wanted to be a paleontologist. And by now we know how that ended.

ELH: We are somehow aligned as one of my earliest aspirations was to buy and refurbish a cargo van; live in it and travel across the country as a DJ. That’s what my dad did that when I was little.

KH: For the career path you are now on, what do you see as the actual beginning?

NG: This is hard as I feel like there are so many starting points. It also feels cumulative, in a way. I would have to say the first time I did a residency was when I understood what it meant to have the attention and support of people I was learning from, and that was in 2011 at the Center for Photography at Woodstock in Upstate New York. There are so many other moments, but that one feels the most tangible in terms of how it all would eventually evolve.

ELH: With me it goes back to my first gallery internship, for which I moved from Toronto to New York at the time. And that was it for me. I was like, this is what I want to do, and that was over a decade ago.

KH: When it comes to your work now, as an artist, as a curator, what is your take on how work is being perceived and understood by the larger public? Do you think there is a right or wrong way to understand someone’s practice/work?

ELH: No, I don't think there is ever a wrong way. That also goes to show why my job is so awesome. I do have a privilege to show work in a certain way and how I envision it with an artist. That is the thrill of it all as a curator. You are trying to present a lens through which people see the work, and you encourage them to see it, but you can never dismiss how someone inherently sees something. It's a subjective experience, and that creates critical conversations either in agreeance or an aversion to it, which is equally interesting.

NG: I would have to agree. I don't think there is a right or wrong way to interpret someone's work. I do feel like my primary mode of operation for my work is just ambivalence, so with that comes a real moving target in terms of what kind of conversations and interpretations come out of the work. As cheesy as this sounds, I like to think of the work as an invitation to have a conversation. I get excited when people just interpret something in a way I would have never anticipated.

ELH: There is an interesting twist to interpretation, though. Sometimes people imply that you have done something egregious or insulting because they misinterpret the work, which we can’t say is wrong because if that’s how they are reading it — that’s their right. But to imply that was artist’s or curator’s intention feels misdirected.

NG: Not just when they are offended, but anytime someone responds to something, you are getting a snapshot of that person. They are revealing something to you about themselves, about how they are interpreting the world and the accumulation of experiences they have had until that point. Sometimes just a smell or an interaction they had before they walked into the space dictates how they perceive and see the work on that particular day, or what type of conversations they want to start.

KH: When you work on something, do you then ever think about how work will be interpreted or how to convey a message stronger? Or in the process of making, do you just work, and the implications of whatever happens after, also come after?

NG: When I am working on something, all the questions that happen along the way I am answering with myself in mind. I don't think about the broader scale in that sense. I know he is a problematic figure now, but there is this David Bowie saying that artists do their worst work when trying to appease the desires of people who are not them. I would have to strongly agree. Some of my most disappointing works have been made in the context of trying to think about some imaginary desire of an audience or a curator or somebody I am making work for. I do this work for myself, and because I want to see certain things in the world. Then I want to share those things and have conversations around it. It's an extreme privilege to be able to do what we do, so I often think, “How can we make this worthwhile?”

ELH: Absolutely. Then, my work as a curator is to go deeply into someone's practice and really understand what a show is meant to say or do for the artist and do my best to channel that. At the same time, I am thinking heavily about the people coming into the show, but more so as a mediator between the artist and the public.

KH: How much of oneself should be given to the public? If we look at artists, how much should they share? Is work enough or they are equally important players?

NG: I would love to separate myself from the work and let that exist separately If I had the option. This is also why I am particular about portraits and images of myself circulating and being attached to the work I create.

These days, so much attention is being placed on the artist's persona and that can dictate what work is acceptable or not. We live in an image-driven economy of attention right now, where the image of the artist is so inextricably linked to the work. But now. when you encounter something that is an unknown entity, you want to have the background information on who made it, what the ingredients are, and who is informing the experience the viewer is having. It's an additional part of this logic and informational system that can also feed into cancel culture, where once a mistake has been made, all other works from that artist can be diminished. Which can be a fucked-up thing in and of itself.

ELH: From my perspective, the answer is whatever the artist wants. One of my favorite artists of all time infamously never appears at their own openings. That doesn’t mean I love or hate the work any less. Their presence in that way is almost irrelevant. What they do is their message. But sometimes, other artists are more open, and we can spend more time together and talk about the work directly, which is also amazing andI’m appreciative of. Personally, the work is enough. I don't think artists should be compelled to do photoshoots and keep up with social media. It should not be a requirement; it should be a personal choice.

KH: The looming feeling of necessity and keeping up with social engagement really needs to be checked. This also deserves to be a whole other conversation, so let's just keep it simple and finish off with where do you both see yourself in twenty years from now?

ELH: I better be retired and chilling in 20 years from now. If I am not doing that, please send a rescue team. [Laughs]

NG: OK! Got you. I have been on this kick where I just want to move to Alaska and fly around in a little plane.

ELH: Yeah, I want to move too. Go back home to Canada, have a small house with solar panels and grow veggies and fruits, don't wear shoes, write a book.

NG: Oh my god, yes, that sounds amazing.

ELH: And when the apocalypse comes, at least I am in the woods.

NG: [Laughs] Well, that’s the title of your book: At Least I Am in the Woods!

Credits

- Text: Katja Horvat

Related Content

DEANA LAWSON: The Selection of Images

JOHN GRAY: Post-American Age

JANUS: Searching for a Sound that Doesn’t Exist

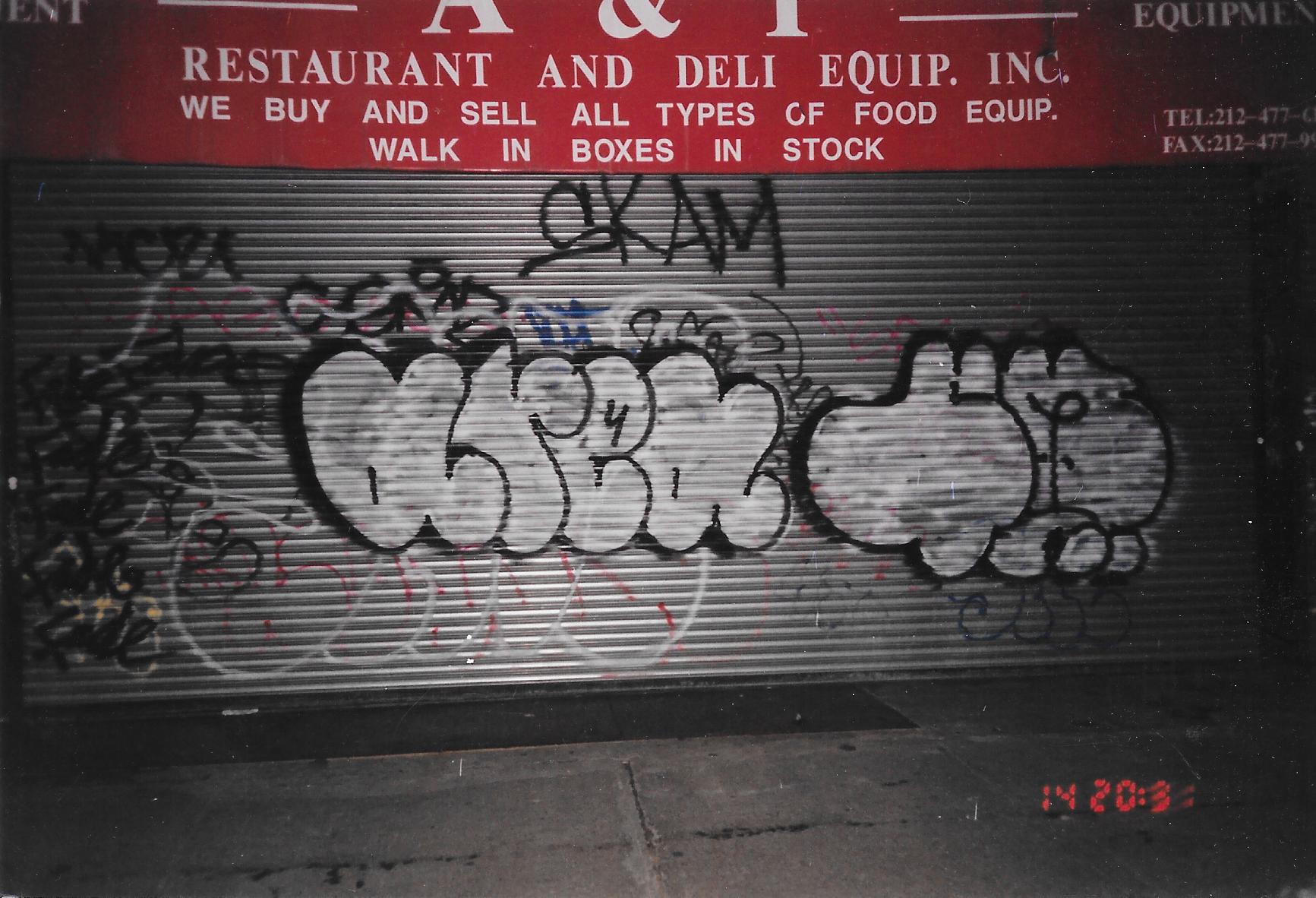

In Conversation: IRAK – KUNLE MARTINS AND BEN SOLOMON

“AMERICA IS ME”: The Life and Times of GORDON PARKS

SMASHED COLLARBONES: Berlin Art Week 2022

SPRÜTH MAGERS: The Art Gallery and the World

Creativity in Motion: On Walks of Life

CULTIVATED ASPHYXIA: “Exposition N°120 (maybe)” at Balice Hertling

I WAS THAT ALIEN: Filmmaker ARTHUR JAFA in Conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST

“It is by far the BIGGEST EXHIBITION I’ve done in a small space over the past 25 years.”