JASON DILL Takes us to Hell and Back to FUCKING AWESOME

Jason Dill isn’t ready to press pause. He is now 40, and how he even managed to get this far is something of a miracle. Known mostly as an iconic pro skateboarder, Dill is so much more than that. He is one of life’s true explorers, following his psychotic intuition up mountains that have pushed the limits of his body—both as part of the athleticism required to pursue a brutal sport, but also in search of the recreational pleasure of getting fucked up.

Sometimes better known for his eccentricities, Dill’s time as a pro rider for Alien Workshop over 15 years solidified his reputation as an iconoclast in an industry defined by iconoclasm. His story is an odyssey that travels from the depths of anarchy to founding his own skate brand, Fucking Awesome. It is an appeal to the creative power of only doing what you want.

Dill’s story is one with an inauspicious start. Born in 1976, he was raised by his mother in California. As he explains: “I come from fucking nothing, man. We come from a trailer park. When I first got money, I gave it to my mom. I got a check for 600 bucks and I gave it to my mom, and she let me go to New York. I would give my mom money, she couldn’t tell me no. If I’m only 16 and I’m paying the rent, then I’ve got some say so.”

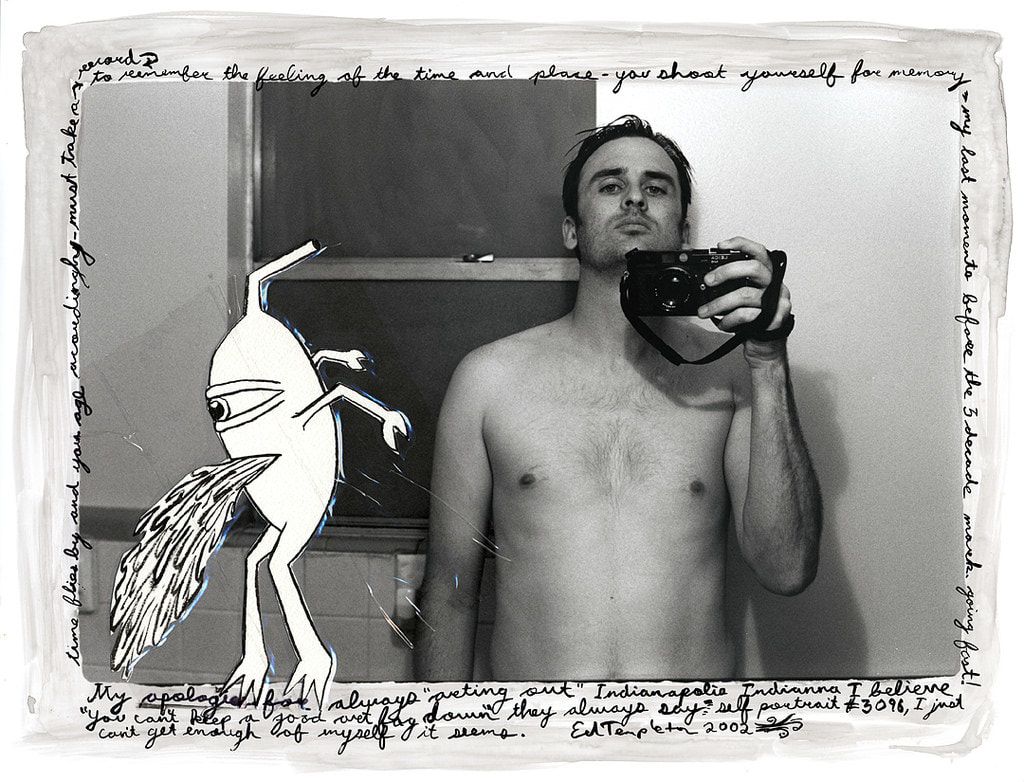

Living in Huntington Beach at that time, he was in close proximity to pro skater Ed Templeton, and this, together with his own drive, propelled him into the sport. At this point in skate style, jeans were oversized and skate shoes were huge. It was DC and Droors. In 1991, at just 12, he appeared in his first video spot for A1 Meats, a skateboard wheels company. It was clear from this early part that Dill was a prodigious and fearless talent, displaying a powerful and effortless style that was beyond his years.

Dill’s career moved quickly, and at age 15, he attracted his first sponsor, Spitfire Wheels. Then he got a spot on the World Industries 101 team, headed up by Natas Kaupas. He was a loud-mouthed kid who constantly proved himself at contests. After hanging out at a competition in Canada with Alien Workshop pros Josh Kalis and Rob Dyrdek, he was added to the team in 1998. From that point on, the ticket for Dill’s permanent vacation had been fully paid for. As Dill reflects back on these early years, he sighs quizzically at how much he was able to get away with: “What kid goes to school until he’s 14 years old, drops out, and then flies around the planet? Usually you get the reverse. You drop out of school and you have to get a job at the gas station. I got rewarded. Skateboarding rewarded me. Skateboarding is totally insane. There have been plenty of times when I should have been demoted, but I was rewarded. Rewarded for my bad behavior.”

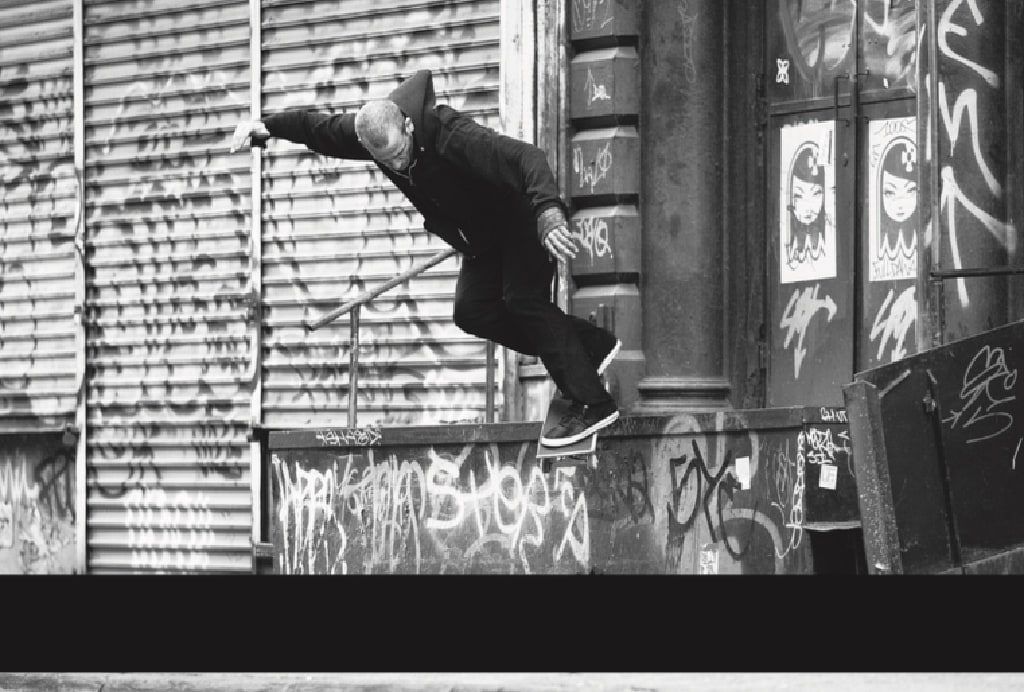

During the purple patch of his eminence as a skateboarder, Dill filmed a part for Alien Workshop’s Photosynthesis video that is widely regarded as one of the most crucial sets of tricks performed and documented. The celebrated line on the video begins with a 360 flip into a fakie shove-it over a barrier, and then, in an almost vaudevillian move, he picks up his board, runs down a flight of stone stairs, and ollies a massive gap down the second set of stairs. Dill still looks back on this fondly as a pinnacle in his career: “Yeah, I mean, shit, I’m real happy that exists. I just think that was the shift of things in my life that really personified everything that was going on with me. I trusted those guys at Alien Workshop, visually. Whatever you guys want me to do, I’ll do it. That was the last video part that wasn’t painstaking. Everything after that was fucking hard and difficult and not as enjoyable. Photosynthesis was the high life, a lot of frivolous times caught on film, and somehow it all worked. It’s strange. It makes me feel weird when people say things like this, but they might have captured the greatest time of my life on there. That was a five-minute video part, filmed between 1998 and 2000, and I’m so goddamn happy that exists. It’s nice to have things in your life that you wouldn’t change in any way.”

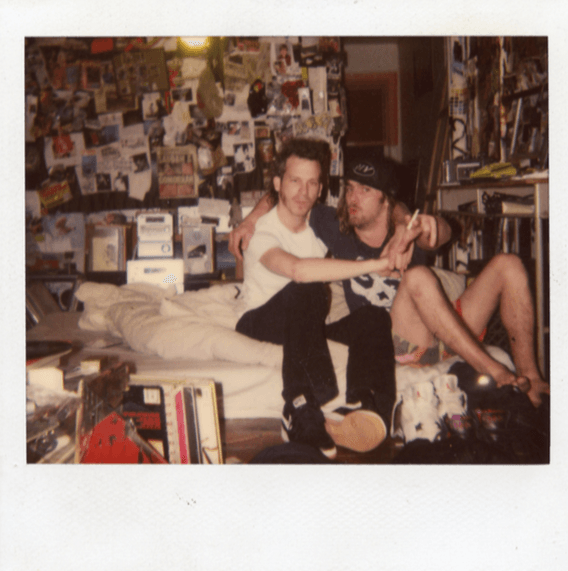

Each step along the way was schooling Dill, and this was definitely not a college education, but the kind of education that you can only receive if you embed yourself in New York street life. The inspiration to move east to New York initially came from his brother Chris introducing him to Scorsese movies. Then it all just made sense: “Once I was 13, I became friends with Gino Iannucci and Keith Hufnagel, and all of these skateboarders from New York. And they were like, ‘You need to come to New York.’ A lot of my first things happened in New York. The first time I took acid was in Queens. My first pro contest. The first time I ever hooked up with a girl in the back of a taxi. All in New York. It’s all magical. I’d never want to come back to California back then. I met so many people when I came that had a giant effect on me, from the mid-90s to early 2000s. Aaron Bondaroff, Dash Snow, Kunle Martins, Gio Estevez, my friend Mikey, so many people around my age that were very much doing their own thing. I learned a lot from watching people and talking to them, basically about the process of making things and living a life as a result of what you make.”

To put this all into context, when Dill arrived in New York in 1994, he was too young to go and watch Larry Clark’s Kids at the Angelica cinema. Another critical landmark appeared that year, and this was the arrival of the Supreme store on Lafayette: “I walked through the doors of the Supreme store in 1994, and it changed my life. For me, I was let into the inside of wherever in New York because of the people I already knew. Then there was the whole thing of meeting people and hanging out all night long. Like talking to Harold [Hunter], and being like: ‘Wait, what? You guys are all in a movie?’ I think about how young I was, and how green I was. I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing. Every corner I turned, I was dumbfounded. But I could not let anyone else realize that. I was stoked at everything.”

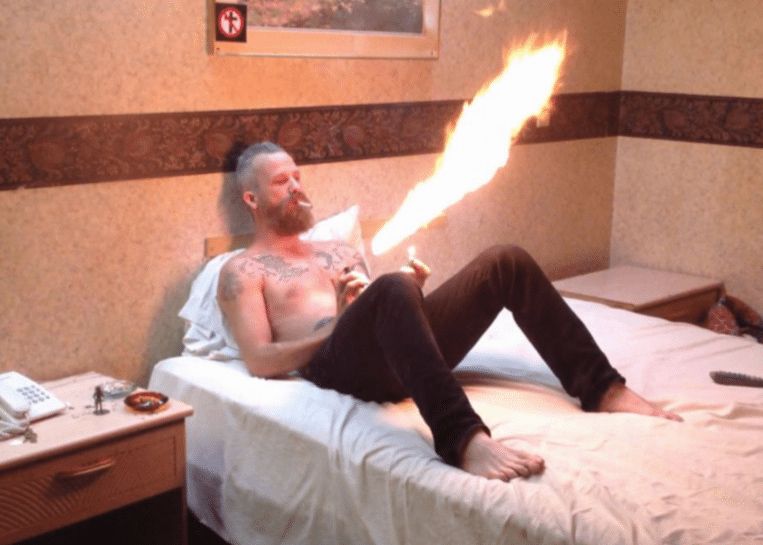

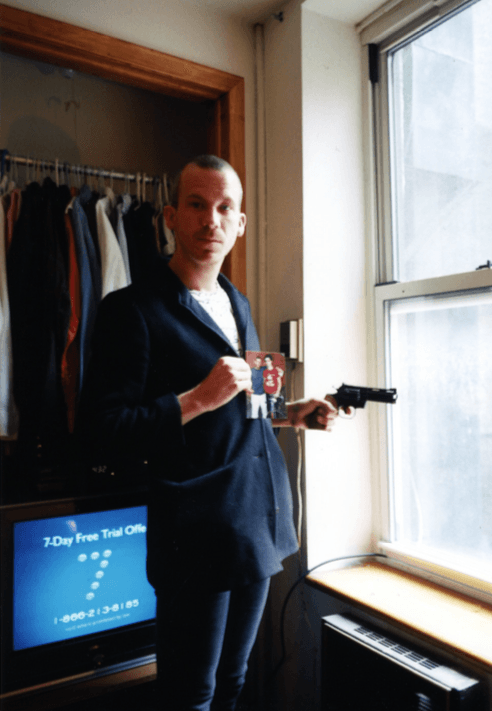

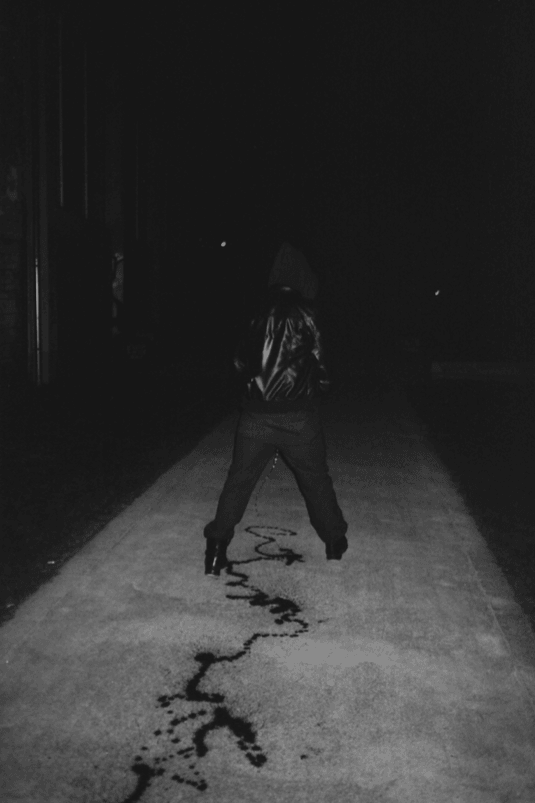

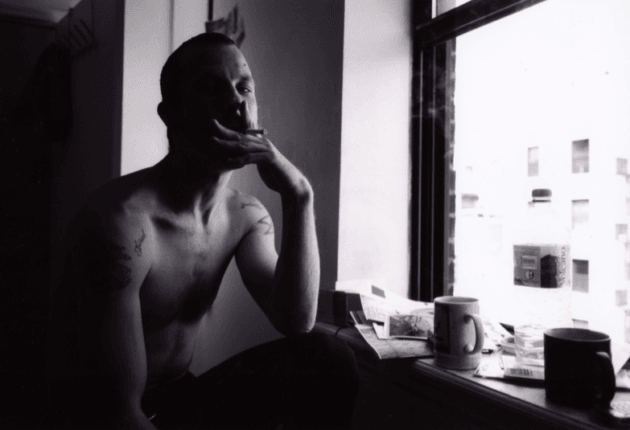

Dill became embedded in the DNA of Supreme. As a fixture on the bench outside the store, he became the embodiment of the brand, modeling for their look books. He took on everything the city could throw at him. That side of New York, at that time, was its own world of unruliness. Dill quickly descended—or ascended—into being a “completely psycho, drug addicted alcoholic.” His life inside and outside of skateboarding became a part of the city’s folklore: “From there in my twenties, I spent over a decade blacking out and being super psycho. And I loved it. I absolutely had the greatest time. It caused a lot of problems and people got really bummed, but such is life, you know. The pictures I took, the people I met, the life I led, the things I got to do, the places I went, I’d never take that away. Well over a decade, but so what? I’m not still the same. I just put different shit in my gas tank. I’m not sober nowadays by any stretch of the imagination, but that’s why I don’t wake up and look back. I had a decade-long vacation. A huge amount of my life that came out of those days helps me now, which sounds totally crazy.”

The Hole on 2nd Avenue became Dill’s home between 2002 and 2005. Just to do something different, he decided to work behind the bar there: “Wednesdays and Saturdays were our nights. It was everything—our gay friends, our straight friends, graf kids, skate, anybody. Old New York people. It was fucked up. The bathroom door was gone. I asked if I could be a bartender there. For a while I did that. I’d do the best I could. Sometimes I’d smoke PCP while I was working. Then I had this girlfriend who was really into smoking crack at the time, so she’d bring some into work. It was so wild. It was so dark in there, so you could get away with anything. It was a beautiful time.”

During this era, he continued to film video parts, but was deep in a wormhole of partying in New York. As a pro skateboarder, his name had become a brand. “The existence of being a pro skateboarder in your twenties—and there’s product with your name on it. You go out and do whatever the fuck you want. I was a pro skateboarder who wouldn’t look at a magazine or touch a skateboard for a year. Because what I was, was a product flying around the world.”

Yet this hardcore life on the frontline of drugs and booze has not been without consequence: “In my case, it was just elevating at times. And the complete opposite at times. Complete hospitalization, being completely broke. All that stuff comes from being a drug addict and an alcoholic.”

Hospitalization would more squarely read as being as close to death as you can be without actually dying. In no uncertain terms, he elaborates, “I had a gastric hemorrhage and I was in pretty bad shape even upon being discharged from the hospital.” This served as an epiphany to slow down a little, along with the untimely passing of two of his closest friends, both from drug overdoses: “A good friend of mine died of a drug overdose and that really slapped me in the face. And about a year before that, another friend of both of ours, he died of a drug overdose. That happened, and I was sober for a couple of years, and that took me up to 34, skateboarding with all of my might. My actions on a skateboard between 33 and 37 brought us to where we are now.”

But Dill is not one to stay on track: “Almost a year and a half ago, I had my first intervention with a bunch of friends. What can I say? I love drugs. All that AA and stuff, I just can’t do it. I get the system, but it’s just not for me. But hey, I’m an asshole. If I stopped smoking weed, what would I do? Start hiking? I don’t even know if I like hiking.”

Not one to blame any single reason for falling into addiction, Dill admits that the life of being a pro skateboarder in your twenties with access to relatively unlimited cash certainly contributed: “It’s tailor made for it. Well, we’re not talking about millions of dollars a year. We’re talking 100,000 dollars a year, maybe more. And you can get real fucked up on a hundred grand a year. It’s like being a rich kid with your dad’s money, but instead, you’re by yourself. You help pay for your family because they’re poor and you can act like you’re rich. You’re completely on your own. You go out and do whatever the fuck you want.”

Dill moved to LA five years ago, simply because he wanted to throw himself back into skateboarding more. He had spent time living in LA in 2001, and his recent move back was partly prompted by the New York winter cutting too deeply into the time he could commit to skating. But that’s not the only reason: “You constantly hear people saying you missed the greatest generation in New York, whether they talk about the 1920s or early 2000s. 9/11 changed everything. Before then, there were so many more skate spots downtown, less of a police presence in general. When you’d skateboard in New York, all the way down Battery Park, all the way up to midtown, the CBS Building, Time Life, you’d know where places had security. After 9/11, the deli had security. New York will always be for young people, that’s what I find anyway. I also just needed to find out what was left of my skateboarding career. Then, luckily, when I came back in, they put me on the cover of Thrasher. I was like: ‘Holy shit, woah, people want to see me skate still. Cool.’”

He decided to leave Alien Workshop, the company that had supported him for 15 years, and just get on with it: “In 2013, it was all just a bit stale. And me being older. And not wanting to die with a company. And Alien Workshop turning into the Titanic. I realized I needed to leave otherwise I’d rust. It was super emotional and gnarly to leave something that you’ve been a part of for that long. But I had to go and do my own thing. In my eyes, there was a lack of something in the skateboard world in 2013. Skateboarding in 2013 felt like it was at the mall. You just put your stuff on an ageing pro skateboarder who has some sort of lineage. It was so squuuaaaare. So accepted. It was a mixture of knowing that it needed to get beat up a bit for being a kook.”

By 2013, there was another watershed moment in his career. Dill decided to seize this opportunity to take life more seriously and step it up a notch or two: “I just thought: ‘Fuck this! I’m gonna make Fucking Awesome a skateboard company and do the whole deal.’ It wasn’t so much coming-of-age, but getting to an age and thinking, ‘Fuck, I can’t just keep doing the same thing.’ I need to re-appropriate what I do and put out what I put out. Instead of maybe putting out skateboard tricks, I was putting out an entire line of everything. That’s what happened, and I wouldn’t take it back.”

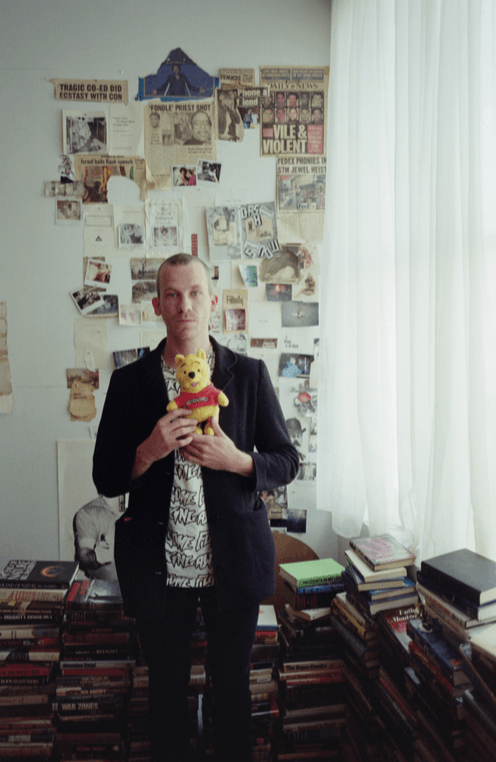

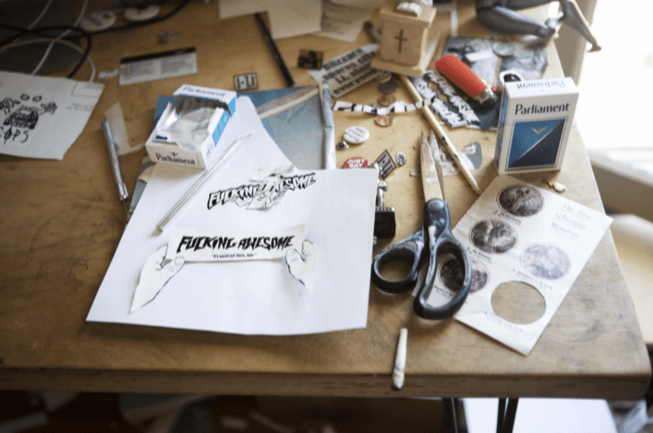

Dill’s role at Fucking Awesome, as he puts it, is “the sole proprietor for imagery.” The brand has one eye on the appropriation of American counter-culture and one eye on provocation. The Fucking Awesome logo is brash and unapologetic. The company’s roots, it could be said, are in Steve Rocco’s approach with World Industries, Blind, and Big Brother magazine. The brand’s attitude was typified by a t-shirt featuring five dictators and George Bush, each with one hand up, emblazoned with the line, “All those in favor of Fucking Awesome, raise your hand.” Outlining his working process, Dill offers: “When you’re making shit, no one gets it. No one understands. I don’t just sit there at a computer moving shit around. I go out in the world, whether it’s Paris or Pittsburgh, or a fucking shop in Stoke Newington that sells old books. I’ll stand there for three hours and look through all that shit. And I might not find anything. But all of this is accumulated and shot out through my system. It’s how the whole operation works as far as making this company.”

By turning Fucking Awesome into a full-blown skateboard company, Dill has put himself in a position he never expected to be in: “I never wanted my own company. A skateboard company. The government is still taking half of my paycheck because I fucked up my taxes for so long. I can’t even take care of myself, or my own company of myself. I thought having your own company would be nothing but a pain in the ass. And guess what? I was right. It’s constantly a pain in the ass. I’ll be out for dinner with my old lady, and I’ll be trying to concentrate on what she’s saying, but at the back of my mind I’m thinking: ‘Oh my god, how many of that did we make? Is it going to sell?’ All these little fucking catastrophes in your brain, and you hang out with anyone, and they just think you’re a weirdo. I’m not complaining about it. It is what it is.”

Dill’s work at Fucking Awesome presents him essentially as an artist—always filming Super 8 footage over the years to add into his video parts, taking photographs that were published in the 2011 book Dream Easy. Dill would no doubt balk at the idea of being considered an artist, but it seems to be the safest catch-all term to capture what it is he does. This is how he breaks it down: “I don’t know much about anything, but I just know how to take things apart and put them back together until it fits or looks right.”

Dill has also taken on the added responsibility of a young team of pro riders who look up to him now as an elder, something he’s not sure he ever expected, and it has presented him with a platform to offer a new generation the power to do exactly what they want: “I don’t know if I enjoy the responsibility, but I enjoy the response. It’s different now. The kids are older. The oldest is Nakel [Smith] who is 22. Tyshawn [Jones] is 17. He’s the youngest and tallest. It is what it is. They’re flying around the planet now. If it wasn’t for my kids on the team, this wouldn’t be what it is. It would just be me, this old white fuck, and no one gives a fuck about me. I’ve been doing the company since 2001, but now it’s a whole different deal. And now I don’t know what it is anymore. I still love it and I’m really proud. But if it ends tomorrow, I’ll be sad because I need money still. We cut the head off skateboarding, and it’s been really great.”