Welcome to Hell: Skater ED TEMPLETON Exhibits Suburbia

|Sam Kavanagh

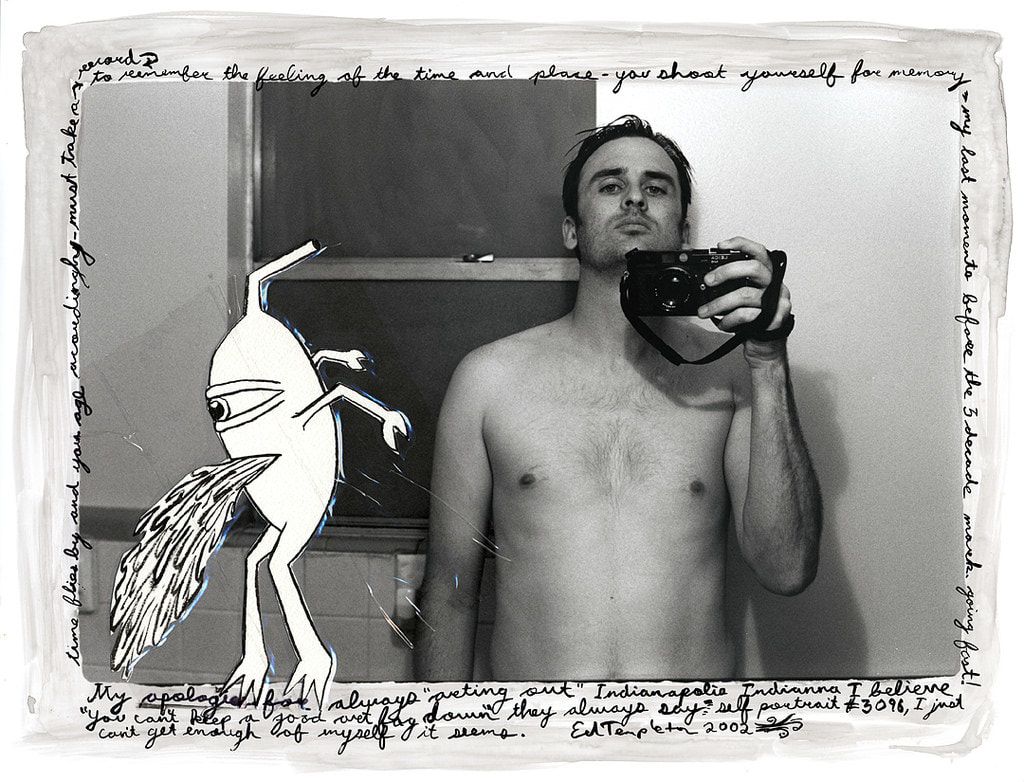

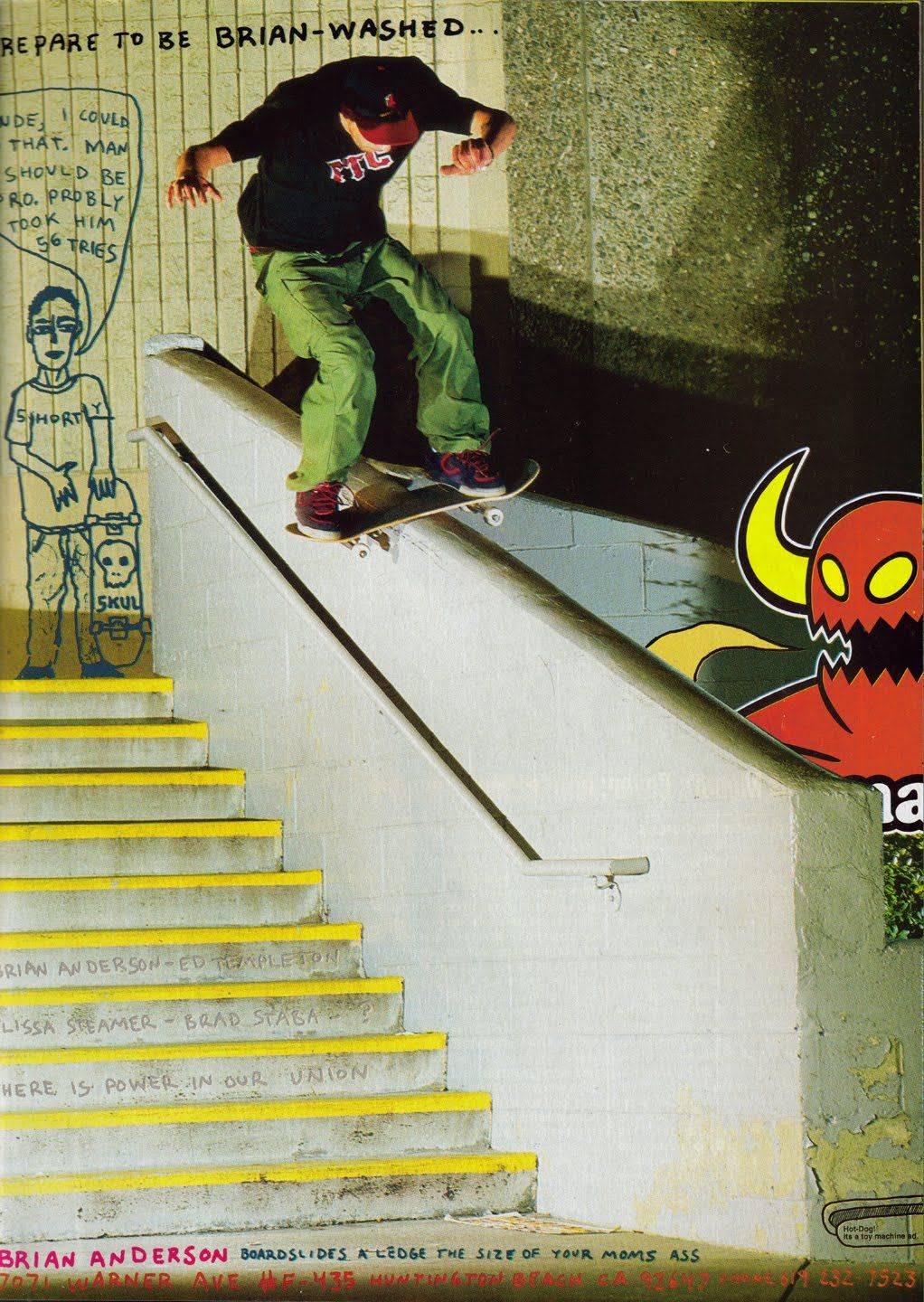

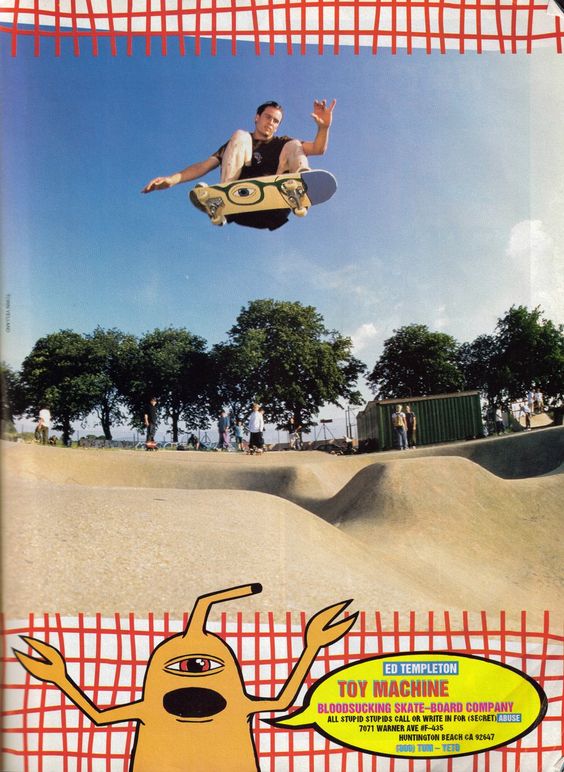

In 1993, California native Ed Templeton – who became a professional skateboarder in the mid-1980s – launched the “Bloodsucking Skateboard Company” Toy Machine. As the artist behind the brand, Templeton designed some of the most recognizable and eye-catching deck graphics in the industry, inventing cult classic characters such as the one-eyed “sect” and devil-horned monster, which still populate skateparks today. Templeton credits his interest in art and the success of Toy Machine to the influence of his grandma, who – in addition to raising him – took him to art galleries as a child.

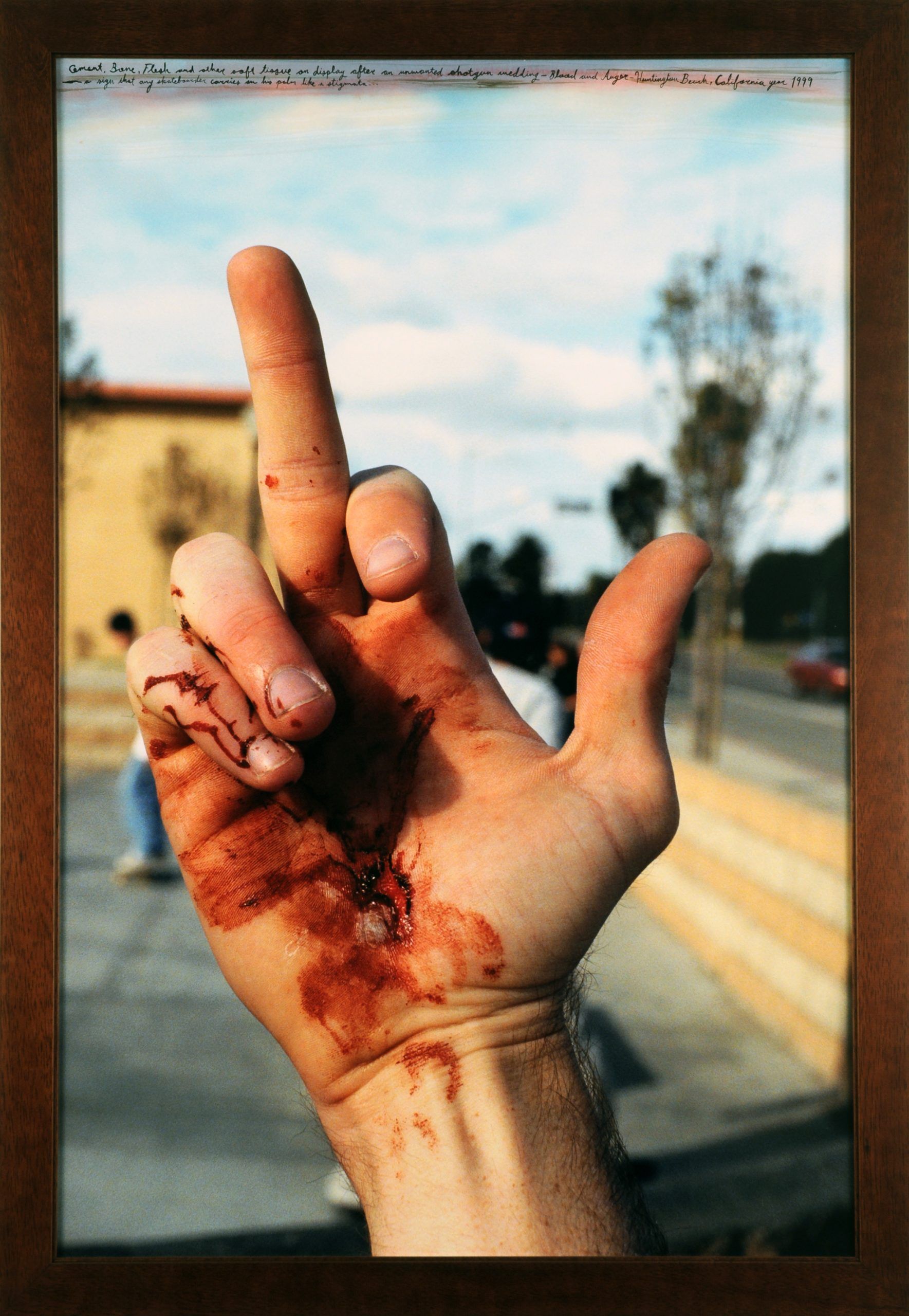

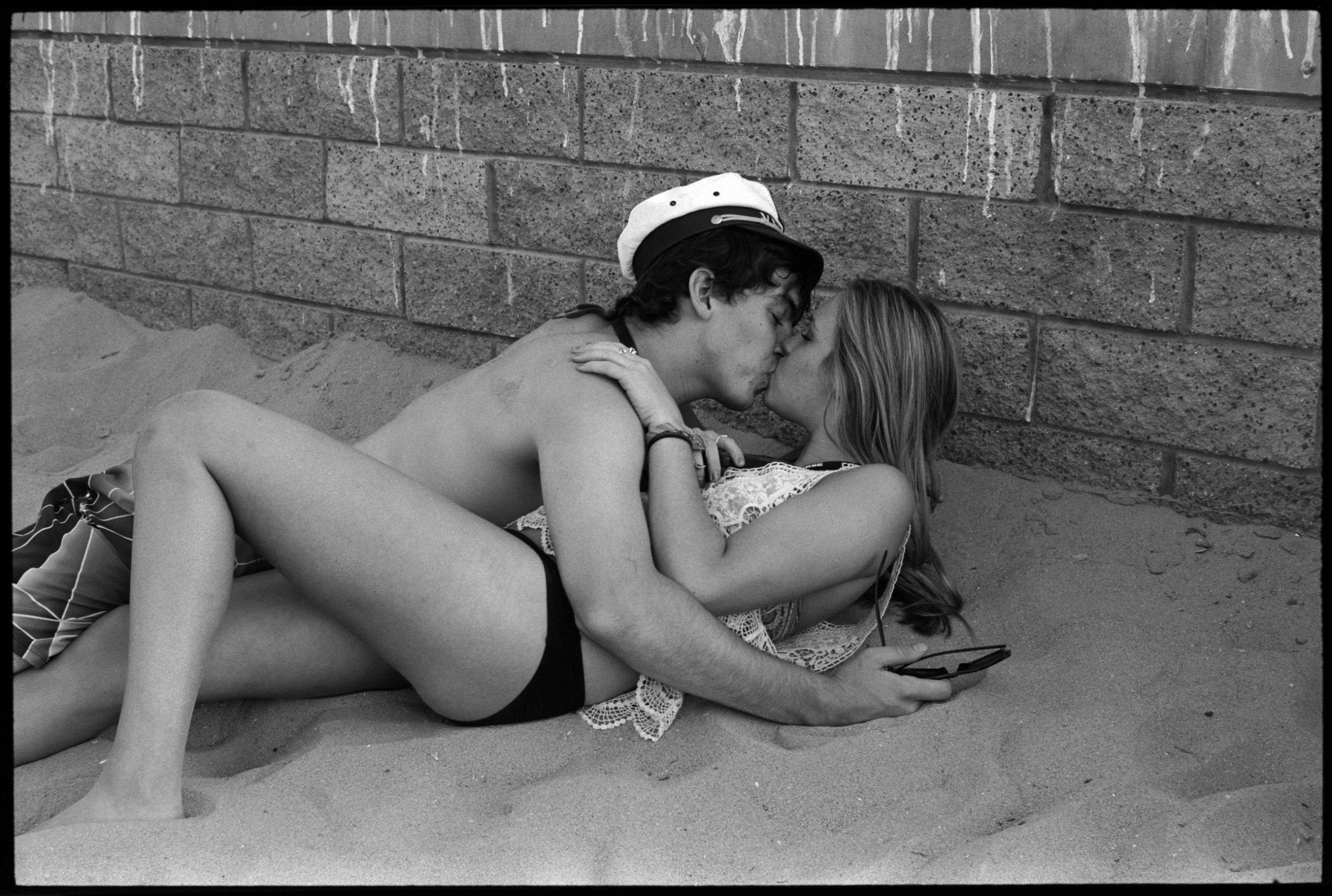

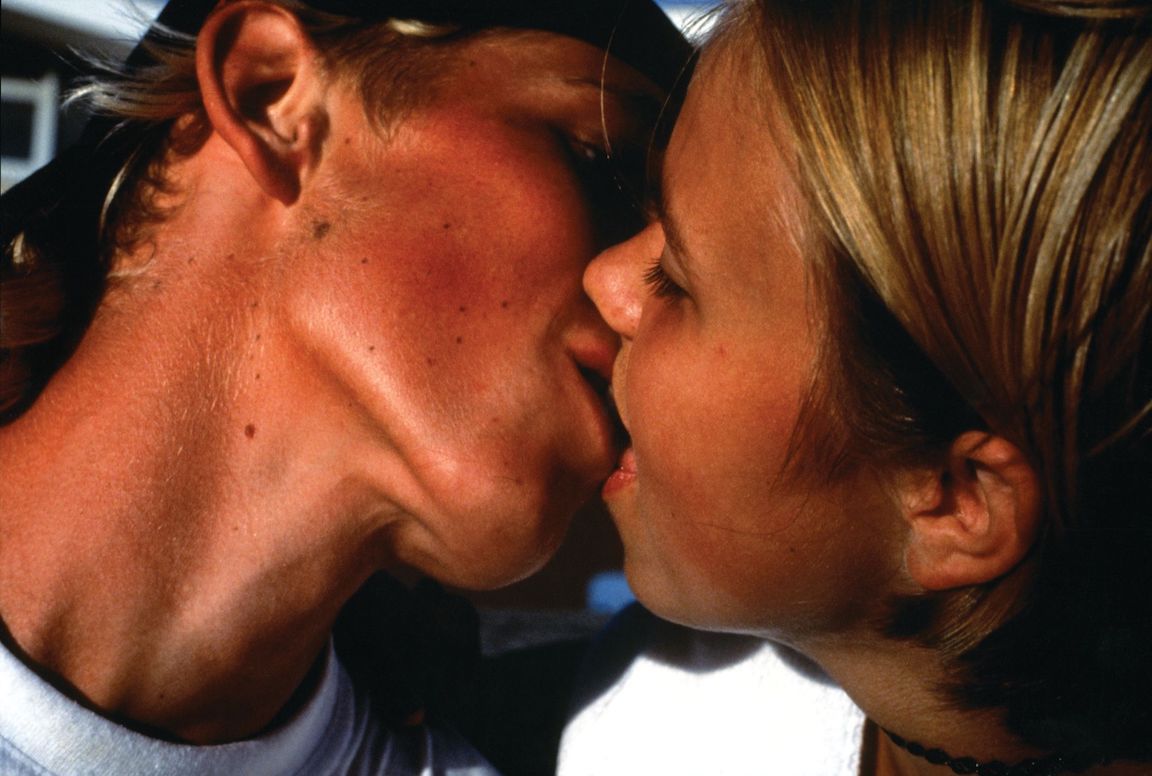

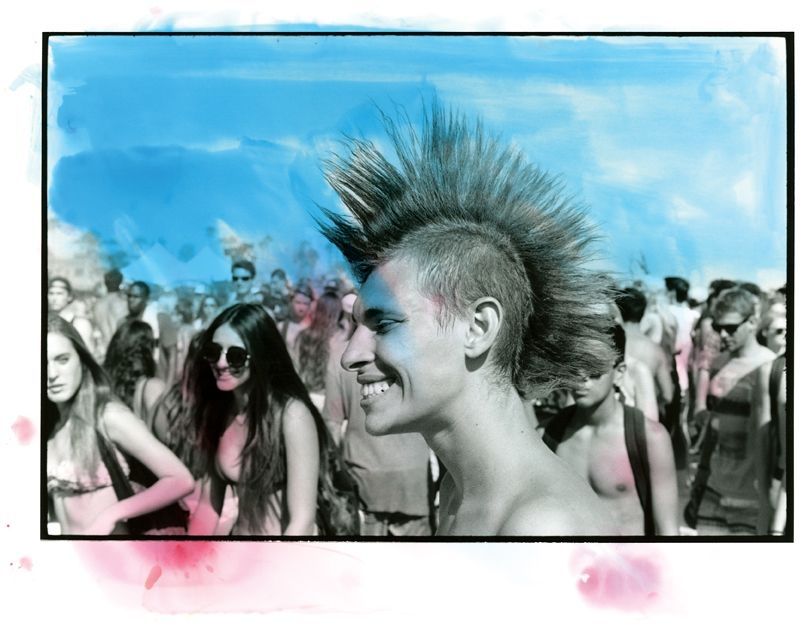

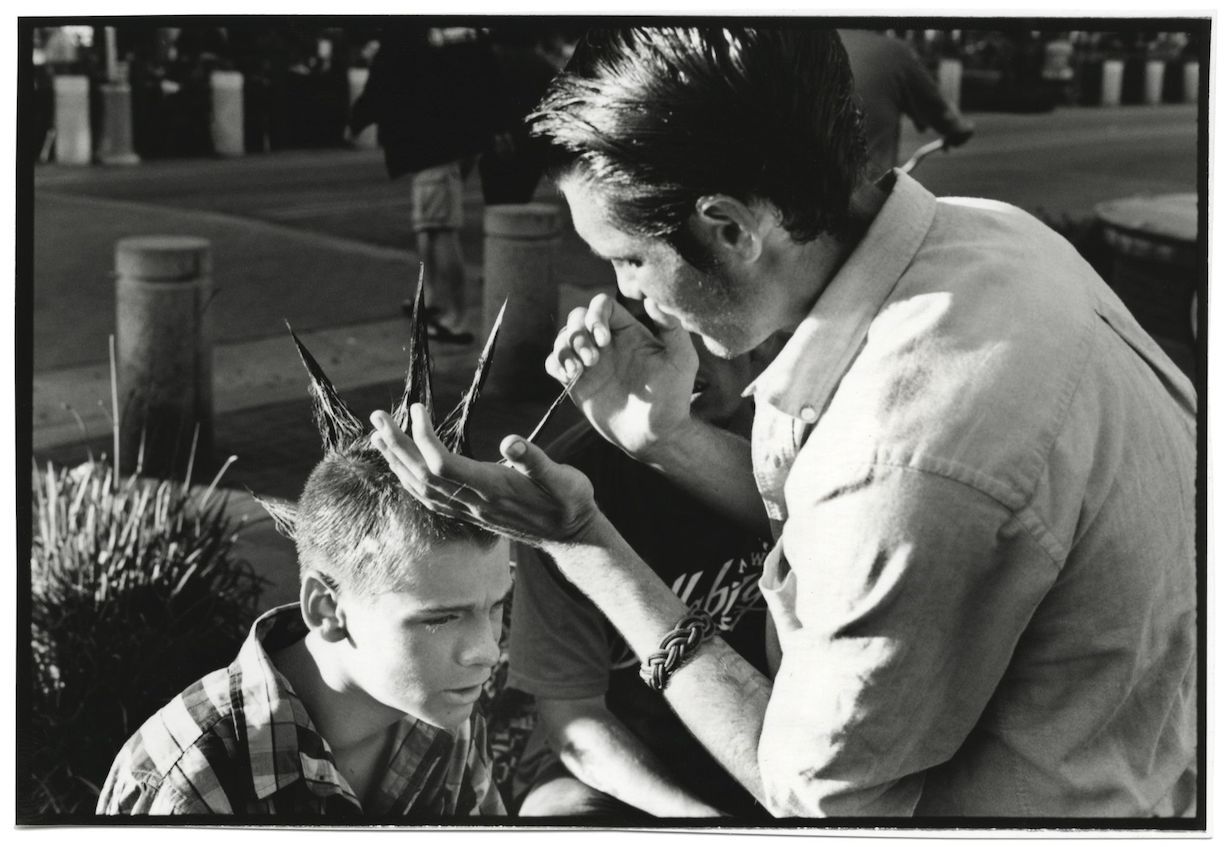

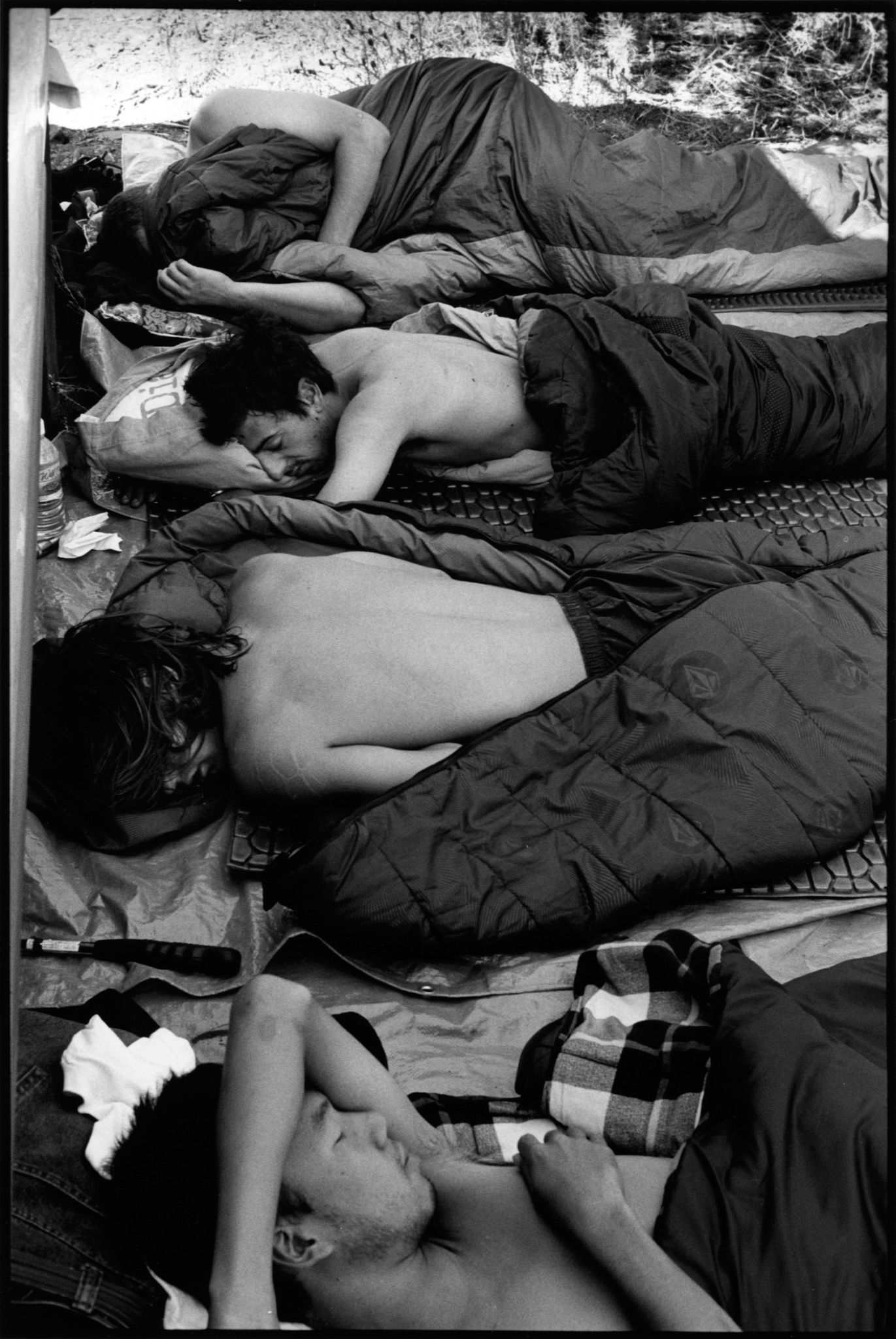

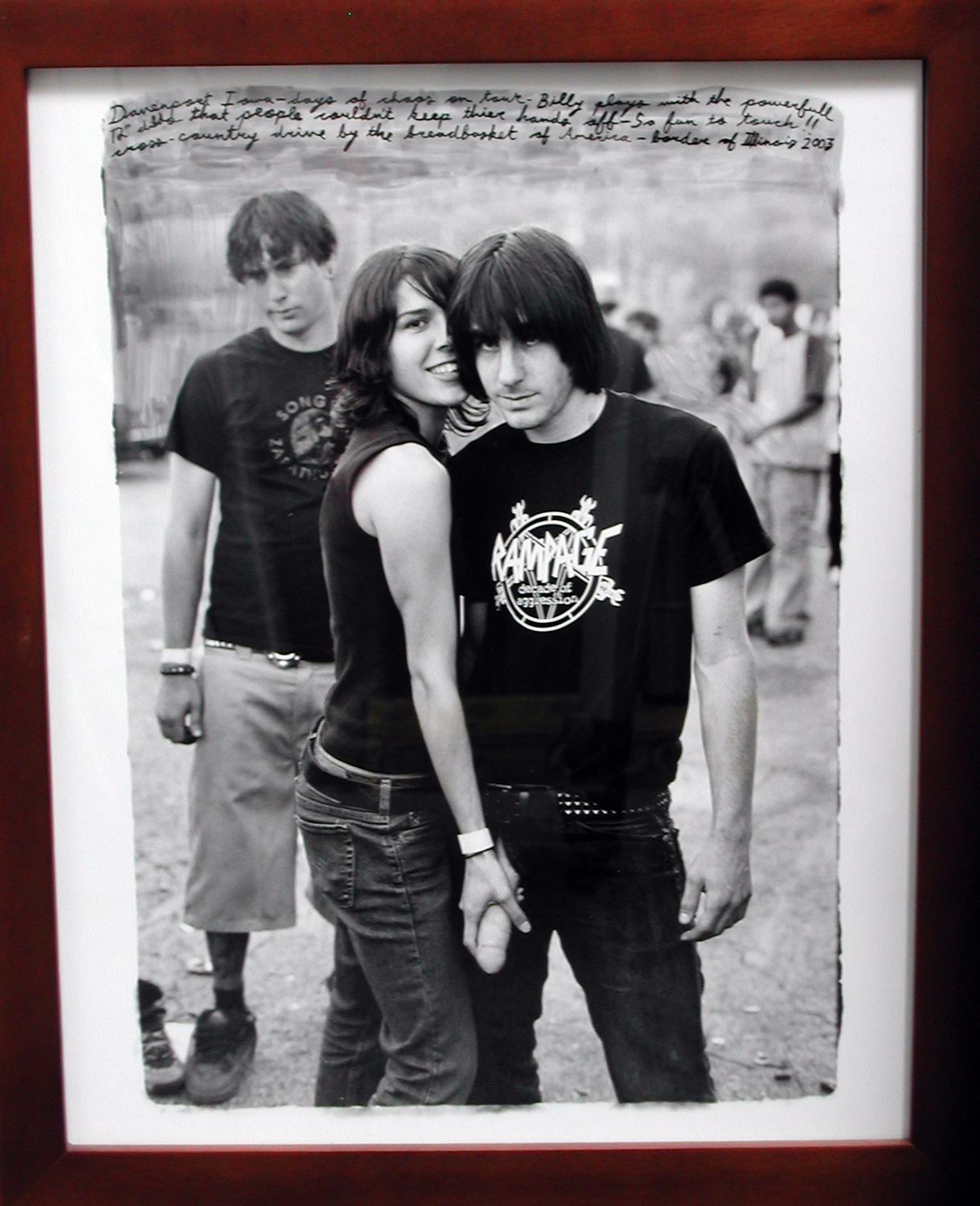

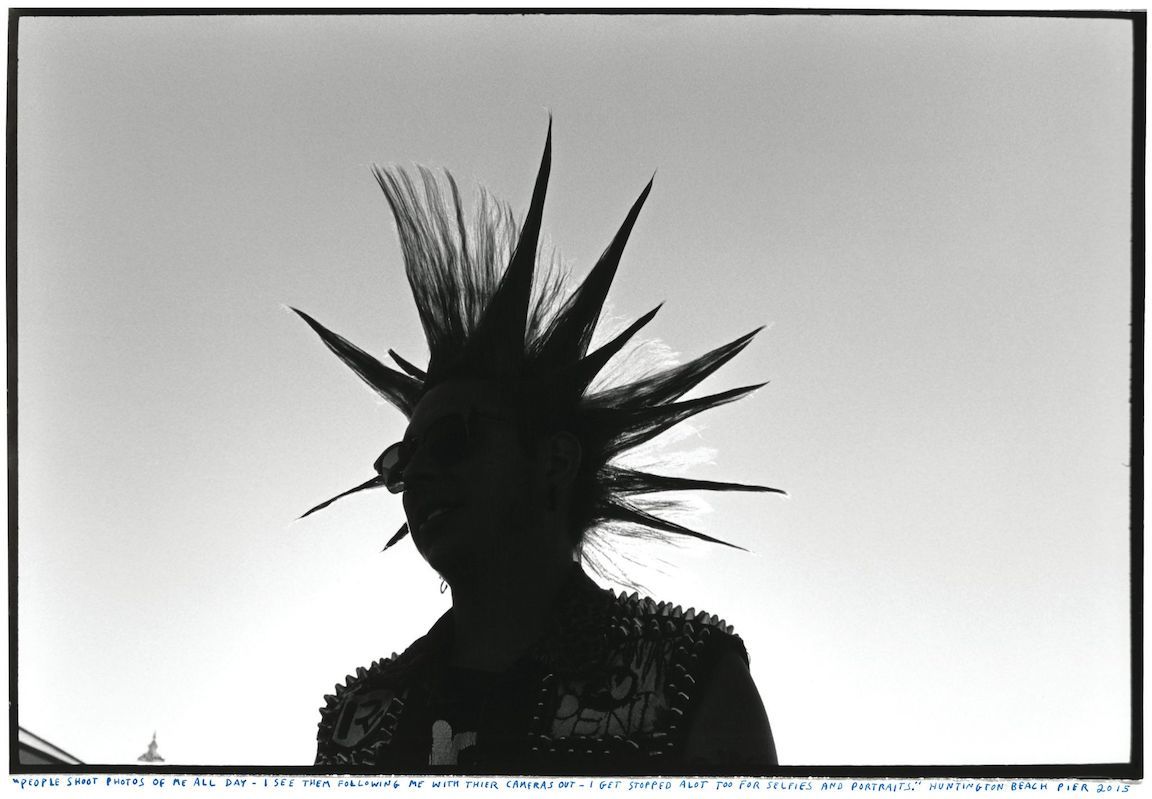

As he toured the world as a skater, Templeton photographed the young people he encountered along the way, creating a raw body of work that has earned him comparisons to youth culture icons like Larry Clark and Nan Goldin. His photographs of teenage smokers, lovers, and punks radiate the charming naivety of youth, capturing the impassioned desire to rebel that compounds under the thumbs of parents and in the numbing cul-de-sacs of the American suburbs. Photographing the beauty and banality of everyday life remains a part of Templeton’s creative practice, which now includes painting.

From now until March 5, 2022, Templeton’s recent paintings, alongside a series of drawings and photographs, will be on display at Roberts Projects in Los Angeles. The exhibition, titled “The Spring Cycle,” unpacks his complex relationship to Orange County, the conservative district in California that he still calls home. “I found punk music and skateboarding which altered my worldview and disappointed my grandfather,” Templeton said. “I was eager to escape this provincial region, but through twists of fate ended up staying here and planting roots among the endless blocks of tract housing.”

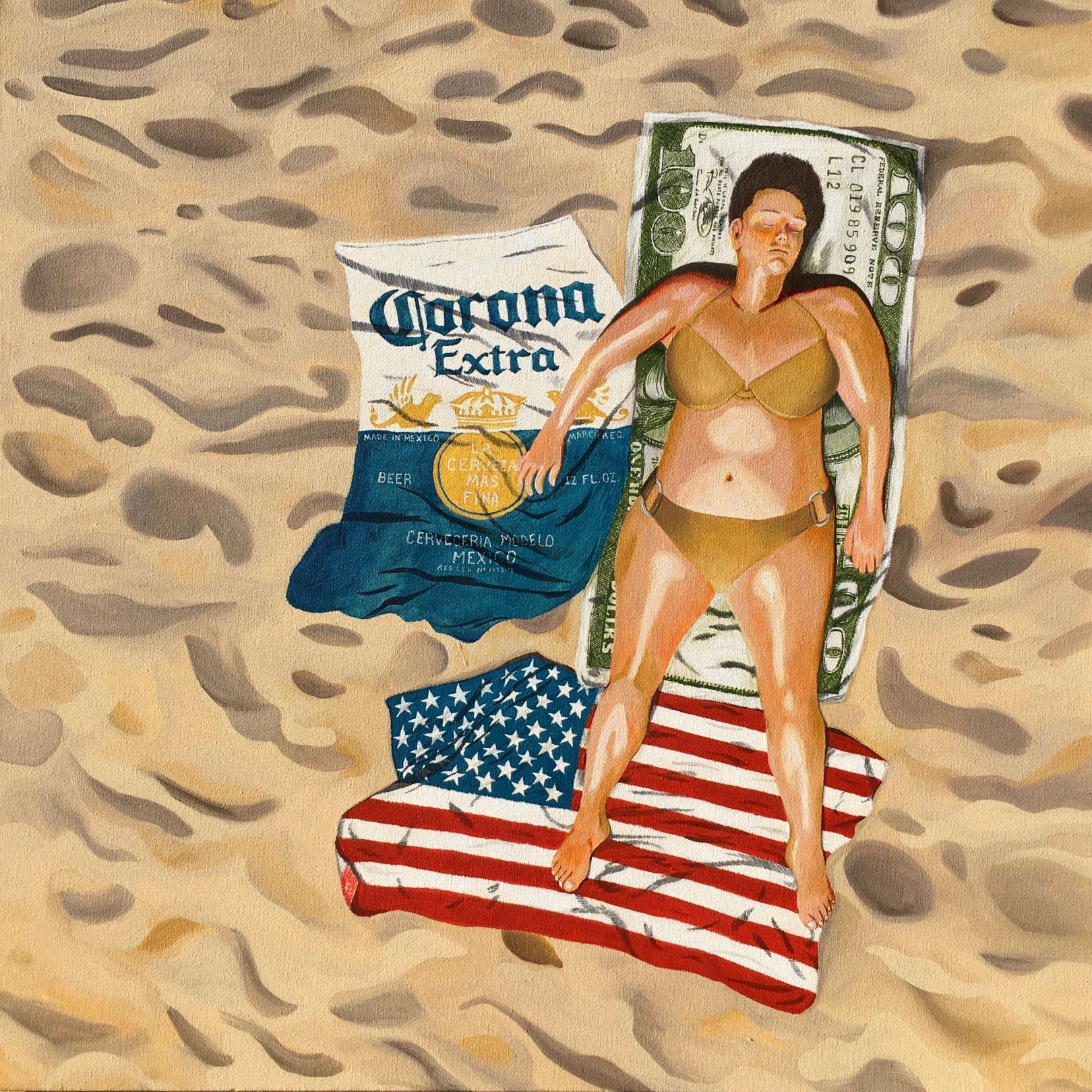

Using a composite photo technique, Templeton paints bits of mischief into the ordinary landscapes of his neighborhood – a Trump and QAnon stronghold littered with religious pamphlets and roads lined with thick, concrete walls. The quirky paintings are both serious and satirical, reflecting his conflicted feelings about the place that has shaped him. The works in “The Spring Cycle,” however, beckon a question that haunts people well beyond Templeton’s zip code. Why do so many of us end up right back where we started?

SAM KAVANAGH: Would you describe “The Spring Cycle” as political?

ED TEMPLETON: I’m criticizing the idea of suburbia – and to some extent, humanity. I always say I have a love-hate relationship with suburbia. I still live here, so I can’t hate it that much. California is a blue state, but where I live in Orange County is very conservative. During the pandemic and the BLM movement, there were also other protests like pro-Trump rallies, and even a KKK rally in Orange County. I’m looking at these themes, but I wouldn’t call the paintings pedantic. They’re more subtly political.

How would you describe suburbia in 2022 compared to when you were growing up, in the 60s?

In the 60s, upwardly mobile Black people moved into cities, which caused “white flight.” Suburban areas in the U.S. exploded in that time period, and I’m a child of that. I don’t mean to say that everyone who moved to the suburbs was a racist, but white fear was part of the zeitgeist. A lot of white people wanted to build a family and thought getting a house with a picket fence and a little backyard was going to be a “safer” place for that family. My grandfather was guilty of that.

The suburbs still have these nice and clean facades which suggest that “everything is fine.” But the people are the same and the problems are the same. Inside the houses, deadbeat husbands are still getting drunk and beating their wives. Homelessness is everywhere. Disrupting these facades is really the core of my work.

In the particular suburbia that I live in, there are a lot of walls, so when you’re driving down the main streets with walls on either side, you can only see people’s roofs. That’s all you get to see of other people’s lives. They’ve become a motif in this body of work, representing what you can see and what’s hidden behind them.

I also noticed a lot of religious motifs.

That’s been an ongoing theme of mine. Religion, and how it affects people, and how it manifests in public. I was raised by my grandparents, who were born-again Christians and took me to church every Sunday. When I got old enough, I immediately became an atheist, after seeing how it changed them. For example, in my work, you can see these religious pamphlets that people pass out on the pier. People take them and inevitably just throw them away, so the ground is covered with them. I have to admit there’s a bit of beauty in them.

Are there any types of people that you are drawn to feature in your work?

A lot of times it is just people living their life here in Huntington Beach, the performativity of it. I’ve always been fascinated by girls doing their makeup in public and casually parading around with very little on. It’s a pretty big contrast to the dress code in other states.

In recent years, skating culture has become popular within a mainstream context, and many creatives and designers alike have looked to the subculture for inspiration. How did you feel seeing the culture transform in this manner?

Up until the early 90s, skateboarders were the trendsetters. Then, as hip hop got bigger, it took over – and started to influence skateboarding. Now it might have come back full circle because a lot of what’s happening in skateboarding alone has made its way into popular culture.

But I welcome it. I’ve always described it as branches of a tree. The act of hardcore, illegal, street skating is still the same, and that’s never going to change. The Olympics and the Mountain Dew commercials, those are new branches – but they coexist with the old. And more are growing. For example, skateboarding is becoming really popular within certain communities in Africa. To me, it’s not a new iteration of what skating is. It’s just a different side of the same coin.

You started skating back in the mid-80s and gained a cult status in the LA scene. Have the values of the sport changed?

People’s approach to skateboarding and the accessibility to it have definitely changed from when I first started out. There seems to be no stigma anymore. In the 80s, there was a certain skater stereotype that I fit into. I came from a messed up family and all of my friends were in the same boat. We were all alienated kids and felt like a band of misfits. Back then, the “jocks” would kick your ass for being a skater. Now, if you’re a skater, you’re like the coolest kid on campus.

If you’re someone like me, who’s lived most of his life before cell phones arrived, social media is a complete game changer. Especially for skateboarding. It used to be that, every couple of years, we would release video content. We would sell a ton of videos and that was our biggest product. Now you can just open Instagram and see the same quality stuff every day. Every kid is putting out clips, and it’s crazy how much the value of a clip has changed. Not to mention the value of photography itself.

As a street photographer, the moments I captured back then creep into my psyche, almost as if I’m haunted by nostalgia. My favorite photographers are from an era before cell phones. The street photographers in the 50s, 60s, and 70s mostly took pictures of people waiting. Now, it’s very difficult to find people who are not on their phones.

Would you say skating is a form of self-expression?

For sure! The way you use and maneuver the board can be somewhat poetic. Skateboarding really has its own poetry with movement that can also be very brutal. The best skaters out there are doing super creative things on weird obstacles – and that’s the essence of it. There’s also a healthy lineage of creativity in skateboarding. So many skaters have gone on to work in visual arts and do things outside the sport. The director Spike Jonze is just one example.

Do you still skate?

Not since last June. I broke my leg in 2012 and that has hindered me a little bit. I was able to recover eventually, but never fully. Part of it is because there are two plates that go down both bones in the bottom part of my leg. If I was to skate again, I’d have to take at least one of those plates out, because there’s no flex in the bone. So, I still skate, but I always have this fact in my head, which ruins the fun.

Maybe you’ll take the plates out one day?

Templeton comeback at 50.

Credits

- Interview: Sam Kavanagh