Every FRANCIS BACON, Ever.

|THOM BETTRIDGE

“What directly influences Bacon is a violence that is involved only with color and line: the violence of a sensation (and not of a representation), a static or potential violence, a violence of reaction and expression. For example, a scream rent from us by a foreboding of invisible forces: “To paint the scream more than the horror.” In the long run, Bacon’s figures aren’t wracked bodies at all, but ordinary bodies in ordinary situations of constraint and discomfort.”

– Gilles Deleuze

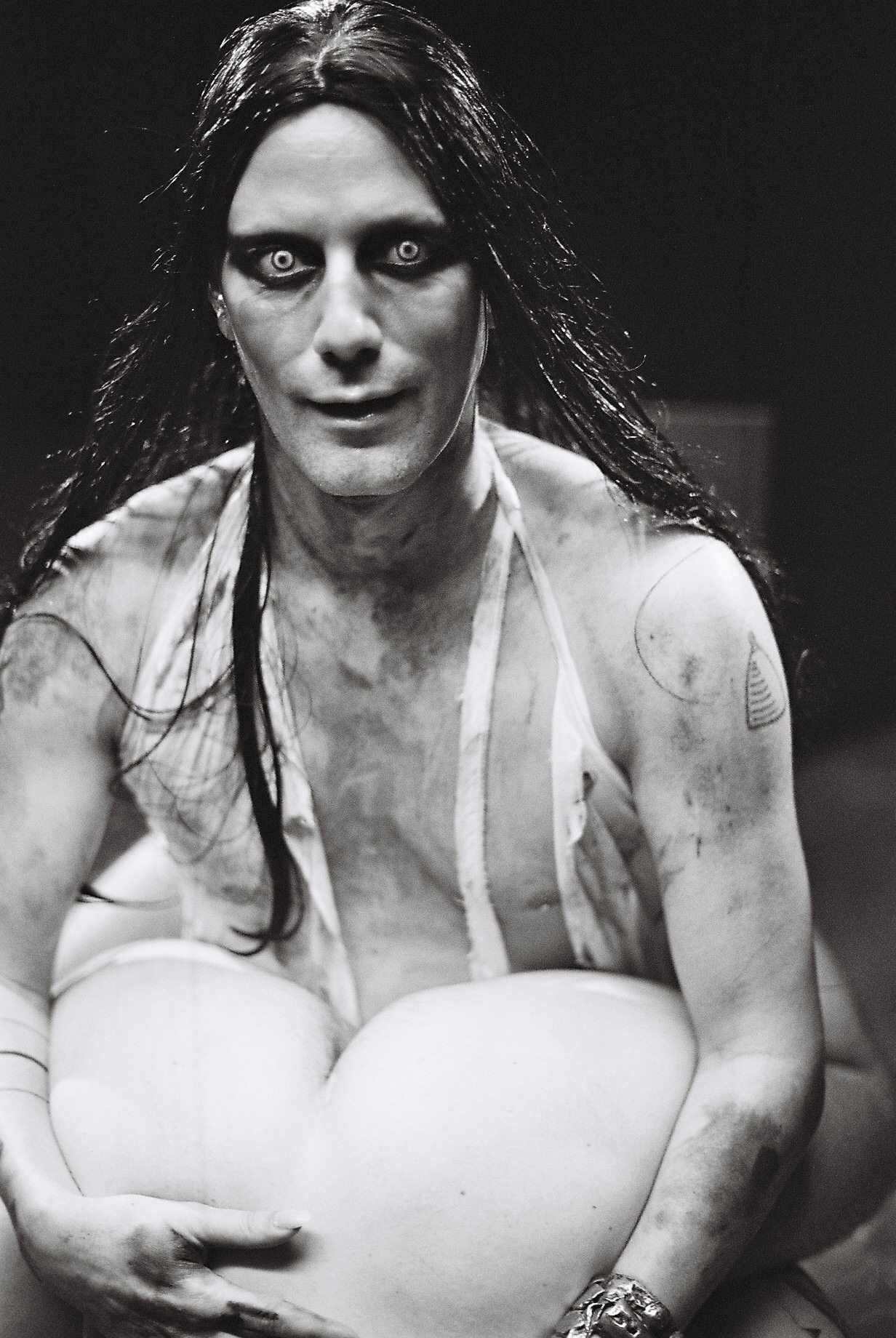

Edited fastidiously over a period of ten years, the catalogue raisonné of Francis Bacon – assembled by art historian Martin Harrison and published by HENI – is a strange and triumphant labor of love. It includes every work in the British artist’s oeuvre, of which are more than 100 never-before-seen paintings. Its 1,538 pages are contained across five volumes, assembled together in a matte-black box set that looks like an ominous hard drive. Leafing through the endless and chronological book enacts a slow dance. Francis Bacon’s primary subjects were humans – bodies – often alone, often in colorful rooms that sometimes have windows or doors. They are torqued, deformed, feeling something page after page. They are crushed by something unseen.

What does WiFi look like when it hits the body? Francis Bacon never asked this question, but his oeuvre provides an answer for it. The philosopher Gilles Deleuze dedicated an entire book to his work, claiming that Bacon was a painter of sensations, one who made invisible forces visible on the human form. In this sense, the painter proposes a study on the grotesque, or rather how the grotesque can become effortless and natural. In this age of constant sensation, in which we dot our world with yoga ball desk chairs and other ergonomic solutions for a life committed to media, Bacon’s paintings predict a human body that is forgetting itself. His bodies often look as though they are on the verge of being cast off, heavy forms in multicolored interiors, propped up by certain social formalities. His men sometimes wear shirts, sometimes dress shoes, sometimes ties. Sometimes they read the newspaper. Sometimes they are naked puddles curled onto the floor. This is what wildlife looks like in the opposite of nature, “the great indoors.”

Sitting in an Aeron chair and flipping through HENI’s Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné, we are forced to remember our bodies again. In this sense, the 15 kilogram box set serves as a type of anchor, a grounding force for our minds as they slip away into the Cloud. In an uncanny prediction of the present zeitgeist, Bacon once said to fellow painter Graham Sutherland, “Nothing matters or will happen until someone makes a new technical synthesis that can carry over from sensation to our nervous system.” These words feel ironic when said by a painter who spent a lifetime studying the tissue of the body. This monumental book dedicated to Bacon’s work presents a similar irony, especially in light of another one of the artist’s proclamations, “When I’m dead, put me in a plastic bag and throw me in the gutter.”

Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné is published by HENI (London, 2016).

Credits

- Text: THOM BETTRIDGE

- Image: FRANCIS BACON, “Oedipus and the Sphinx After Ingres,” 1983