How to Survive with Kembra Pfahler

|VITTORIA DE FRANCHIS

East Village performance queen, pioneering feminist, and fashion muse Kembra Pfahler has expanded the boundaries of performance art through provocative interventions at CBGB’s in the 1980s and CIRCA’s worldwide screens today.

Founder of the glam punk rock band The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black and co-initiator of Future Feminism, Pfahler left Los Angeles in the late 70s to “learn to be herself” in New York and eventually became an icon of counterculture. On a sunny afternoon, we sat together at London’s Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, where she was residing during her 12-week project for CIRCA, The Manual of Action, and talked about life philosophies, beauty, nudity, feminism, modeling, and the future.

VITTORIA DE FRANCHIS: The Manual of Action is one of the first projects you did in the 80s after moving to New York from Hermosa Beach. It is now being presented as a 12-week course by CIRCA online and on worldwide screens. What is the project’s genesis?

KEMBRA PFAHLER: When I moved to New York in 1979, I went to the School of Visual Arts. There, I had two fantastic teachers: Mary Heilmann and Lorraine O’Grady, who taught Surrealism and Dada. It was the first time in my life that I started to learn about art history and methodologies from other generations. In that period, I started being involved with an alternative gallery called ABC No Rio, a space basically given to us to curate. I met my first husband, Samoa [Moriki], and we started curating, doing performances or actions at the gallery. I always wrote about my live performances and drew pictures of them which I started calling “nonfiction illustrations.” That was the start of The Manual of Action, a way to document and understand what I was doing. It wasn’t a directive text or a manifesto. The Manual of Action was a way to figure out what my vocabulary was, it was the start of a new language.

VDF: You eventually started teaching your philosophies around “Availabism”—making the best use of what’s available—in worldwide art spaces and educational institutions such as Columbia University. Did you envision The Manual of Action as a practice that could also help other artists?

KP: I started teaching because other people started asking me to, especially young artists in need of support on how to build things or how to resource things like free art materials and where to work. I shared what I thought was missing in art schools—how to tangibly and psychologically prepare for an artist’s life, since they never really tell you what to expect after graduation. I always suggested never to complain or worry about what you don’t have and to work towards what you can have. That’s Availabism. I showed my students the possibilities of how to survive in a difficult city like New York, how to curate performances, how to do bookings in nightclubs or galleries, and how to do proposals for museums. I shared what helped me the most when I started being an artist. In the 80s, I was very lucky to meet people like Jack Smith and Mike Kuchar, who encouraged me to continue doing what I was doing, as there weren’t many people doing such extreme work. When I teach, I feel like I am continuing the legacy of support I had and helping other artists find their way.

VDF: Over the past four decades, you have been part of and led various collective projects, such as Transgression Cinema, The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, and Future Feminism. How did your community come together?

KP: When I was in Los Angeles, I was part of the first wave of LA punk rock, which you can learn about in The Decline of Western Civilization by Penelope Spheeris. During that time, I witnessed extreme performances by artists such as Diamanda Galás or Johanna Went which really empowered me. When I moved to New York, I began trying to make a living through performances, inspired by the bold acts of incredible women in unconventional venues. I was still young and people were not inviting me to perform in galleries or museums and so I started to approach punk rock clubs as CBGB or The Peppermint Lounge. When asked what I wanted to do, I’d simply say, “I have no idea. Just give me a night, and I’ll create something.” We had to create our own scene; there wasn’t already one we could just become part of. My community became the people I worked with: Samoa, with whom I founded The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, Valerie Caris, a painter from Massachusetts, Gordon Kurtti who died of AIDS at 27, Jack [Water] and Peter [Cramer] from the P.O.O.L. dance company, Nick Zedd… Not everyone liked what I was doing. I remember Jonas Mekas telling me, “Why are you making yourself so ugly?” And I’d reply, “What are you talking about? I’m not ugly; this is a costume, and it’s beautiful.” I always had a feeling that what I was doing was very beautiful.

VDF: You grew up in Southern California, where Hollywood’s stereotypes, especially concerning the female body, heavily influence aesthetic standards. What brought you to suggest a different kind of beauty through your work?

KP: I wanted to present my own idea of beauty as I didn’t resonate with the one that was being pushed around me. It took many years for people to understand what I was doing. At a certain point in the 90s, I got an invitation to model for Calvin Klein in my regular look with my daytime makeup. Before that, everyone used to tell me to keep my hair blonde and not wear that crazy punk rock makeup and make myself look more normal and attractive, as a young female “should look.” Luckily, I had met other people in LA who were trying to do things differently and didn’t care. One of them was Kenneth Anger who was from Santa Monica. I always knew there was a place for my work. It never really mattered if I was popular or not, what I cared about was to exist the way I wanted to.

VDF: You’ve boldly embraced nudity in both film and live performances, disregarding criticism and stigma to become a feminist symbol. Why did your body become an integral part of your practice?

KP: When I was a young girl in Los Angeles, I constantly got criticism from other adults, both male and female, who made comments on my appearance. “You would be so beautiful if you lost 20 pounds.” How harmful is it to tell that to a young woman? I grew up with so much shame about my body. When I moved to New York, I needed to reclaim my body and learn to love it; this is why I started working with it. When I started being invited doing performances in my 20s, I just though what could be the most extreme and ridiculous thing I could do. I was sitting in my apartment, opened the fridge and there was only an egg. That was the start of “Availabism”, I decided to perform standing on my head, naked and crack an egg between my legs. The first nude works truly empowered me. I recommend people reclaiming power in any way that feels right, not necessarily through extreme physical acts. Cookie Mueller humorously remarked, “Once you show your vagina, you’ve ruined your life forever,” which I find true. Performing naked is serious; it’s a lifelong commitment. People are not going to talk much about the artwork you’ve done but about the fact you didn’t wear clothes.

VDF: Ten years ago you initiated,Future Feminism—a movement advocating for genre equality and ecology—with Anohni, Johanna Constantine, and CocoRosie. Together you wrote “13 Tenets”, a series of principles starting with “The subjugation of women and the earth is one in the same” and ending with “The future is female,” which eventually became your manifesto. How did these come to life?

KP: In 2014, we were invited by the gallery The Hole in New York to do an exhibition. Even if the idea that the future is feminist already existed, no one was talking about feminism the way we did in New York at the time. We wanted to reinsert the discussion in the art world because it was not “cool” to talk about it and so no one did.The basic underlying tone for our tenets was the analogy between women and the earth, as the same violence is being done to both. Despite all the internal political issues, the fact remains that we won’t have any opportunity to discuss them if we don’t have a place to live. The harm we have caused to the planet has escalated to such an extreme degree, it’s shocking that we are not all protesting about it on a daily basis. Ironically, we wrote the tenets in stone—rose quartz, to be exact—but the whole point was just to start a discussion and raise awareness on the fact that that the world still devalues women and it needs to be fought, now more than ever. The “13 Tenets” of Future Feminism are not laws but starting points for discussion and hopefully change.

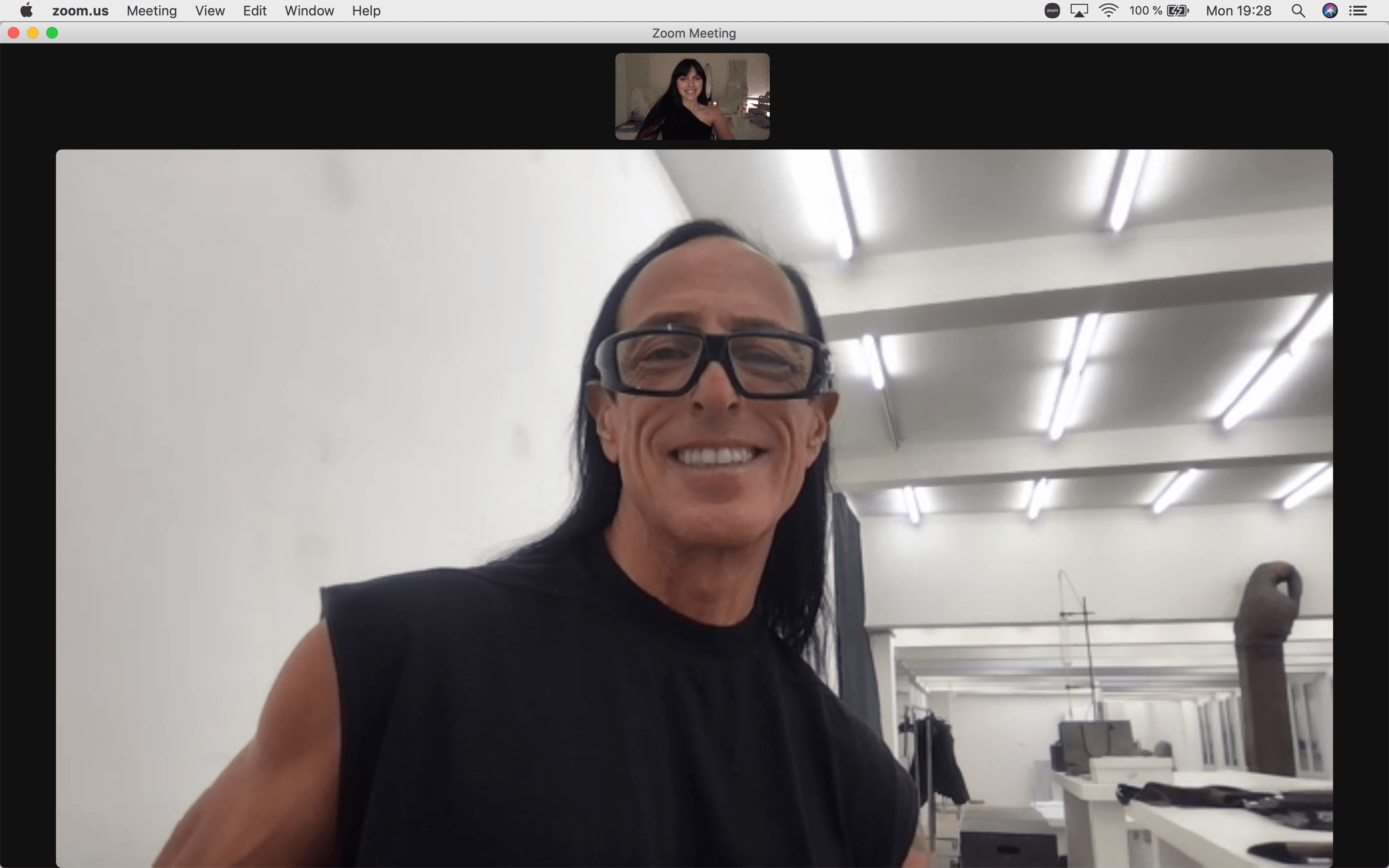

VDF: Calvin Klein, Helmut Lang, Mugler, and Rick Owens are some of the designers for which you have modelled. With Owens, you established a long-lasting collaboration and friendship which culminated in a capsule collection, released earlier this year. When did you meet Rick?

KP: I was introduced to Rick in the early 90s by Bryan Rabin, who was in the punk rock scene, and I immediately thought he was an artist. He had an art studio and was always cutting up things and making sculptures. Rick used to say he was not an artist. He has always been so humble about his process. Yet everything he touches becomes a work of art, and he’s just gotten better over the years. The first thing we did together was “Black Beauty,” his debut fashion show. I was modeling all of his clothes, standing in front of the film screen with The Goddess Bunny by Nick Bougas playing in the background. I haven’t worked with Calvin Klein or Mugler or any of the other fashion brands the same way I worked with Rick. We did an exhibition during FIAC in 2019 at Centre Pompidou and so many other things. At the beginning of the pandemic, we decided to work together on a capsule collection. He was so patient with me as I had no idea what I was doing. I would send him these Flintstone-like kind of drawings and he would explain to me how to transform them into fashion illustrations. It took us around four years to make it happen.

VDF: What’s in Kembra Pfahler’s future?

KP: At age 62, I can say I know less than I’ve ever known. I still want to grow and change and thankfully I can do that through my artistic practice. It’s time for me to do my best work, that’s my priority. There are a lot of things coming up soon: I’m performing at MoMa PS1 with my band for the Pride, doing a solo performance around Availabism at Terraforma Exo in Milan in mid-June, planning a performance gala with CIRCA in London to celebrate the project we did together, and finalizing a book with Rizzoli which will be out next year.

Credits

- Text: VITTORIA DE FRANCHIS

Related Content

Discovering the Aura with Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

Taylor Swift Is A Virus

Who the fuck is Vaquera?

Gross AI Spam with Cory Arcangel

What Karl Marx Taught KENNY SCHACHTER About the Art World and Classic Cars

Choreographer ADAM LINDER Dances for Hire and Disrupts Contemporary Creative Economies

Brenda’s Business with RICK OWENS

Primal Beauty Advanced Technology