Choreographer ADAM LINDER Dances for Hire and Disrupts Contemporary Creative Economies

|JEPPE UGELVIG

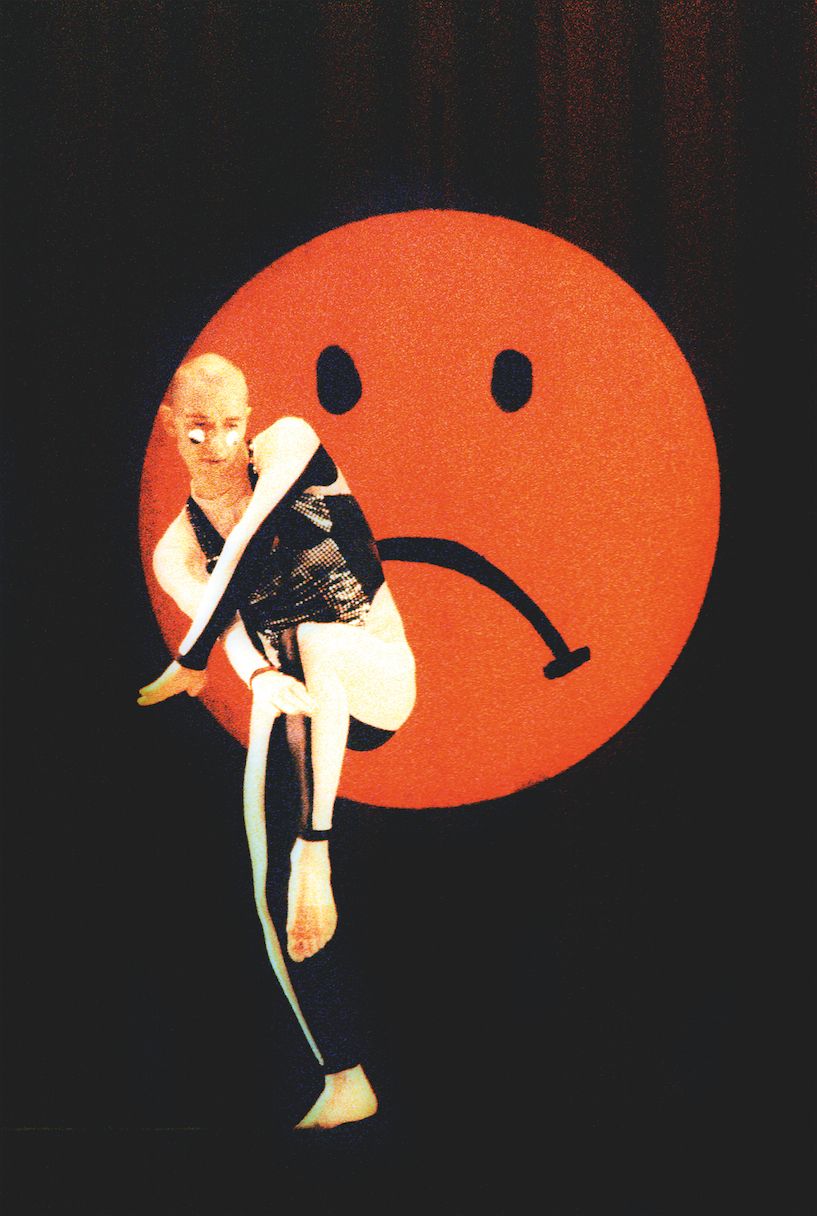

“I’m riding, I’m riding, I’m riding…. Catherine Damman,” Adam Linder chants while he circulates the empty room skippingly, as if to clear its energy. It’s Thursday at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and the dancer and choreographer is for the third consecutive day presenting his newest choreographic invention, entitled Some Riding. Opposite a small hallway, in which a magnified artist’s contract is exhibited, dancer and collaborator Frances Chiaverini, having called upon a different name (“Sarah Lehrer Graiwer”), hypnotically enacts a form of associative critical text in bullet-point form while synchronizing her utterances with a distinctive popping of her limbs. Chiaverini informs me as she moves that “popping” (the rapid contracting and relaxing of muscles resulting in a series of distinct bodily punctuations) is actually a dance form, originating from Fresno, California in the mid-1970s and attributed to Boogaloo Sam from the television show Soul Train (Frances informs me as she moves). The couple is dressed in a utilitarian costume consisting of a white t-shirt, a deep burgundy “skort,” suspenders, and a neck-tag, each labeling them with the essays they are embodying and performing: Special Economic Zone and There is No Such Thing as The Body. Their visceral choreographic embodiment of written texts (commissioned by Linder himself) collapses the critical distance that we’re used to in a culture dominated by linguistics – suddenly, the dynamics of the body affect the text, just as the text affects the body.

Through his touring “services,” Linder offers a critical reflection of his immediate art-showing environments, whether that be a buzzing art fair, a visual arts institution, or in the office of a private collector. He presented his previous work Choreographic Service No. 2: Some Proximity at the booth of his Berlin gallery Silberkuppe at Frieze London in 2014, where an art writer’s witty critical prose was performed via energetic gliding movements. As a service that can be bought (antithetical to most choreography) on an hourly basis, he imagines a format for dance outside the theatre, exposing the real-time economic principles that support dance and most creative labor: a sort of travelling contextual critique-cum-choreographic spectacle.

But Adam Linder’s poignant critique of the economic and institutional structures does not hail from any academy or art school. Born in Sydney, Australia, he began dancing at the age of eight, and at 13 he went into serious training in classical ballet. At 15, he was scouted by the British Royal Ballet School and arrived in London to train at one of the most prestigious institutions for dance in the world. Although proud to have been admitted, he knew almost instantly that his future did not lie in the classical institution with its old-fashioned repertoires and hierarchical companies of 90-plus dancers.

It was a broken foot after three months of training in London that enabled Linder to look beyond the insulate chambers of classical ballet. During his compulsive rehabbing, he spent his time roaming the many galleries and museums of the capital, and exploring the alternative dance scene housed in the city’s various smaller studio theatres. After leaving the Royal Ballet School after 18 months, a short contract in Holland and freelance work followed, subsequently working with the British iconoclastic choreographer Michael Clark.

Linder seems spaced-out but animated as we meet in the institute’s cocktail bar after his 3.5 hour performance (a short one, compared to the other days where Linder and Frances would do two of such sessions daily). As I buy him a glass of wine, we discuss the institutional backdrop of his performance, and he makes it clear that he is, before anything, a choreographer – and that choreographic activity will always be the source of his practice.

JEPPE UGELVIG: Was there a moment when you started thinking about your dance practice in more discursive or conceptual terms?

ADAM LINDER: I stopped performing for people in 2011, the last being for Meg Stuart in Berlin. I think I just started to realize through what I was seeing and what I considered to be relevant that I was much more interested in approaching dance from a conceptual position, rather than an expressive or movement-research position. Conceptual dance had its real breakthrough in the late 1990s and early 2000s with people like Jérôme Bel, and I think a lot of the expressivity, virtuosity, and specificity of movement got somewhat extracted out of dance, transforming these works into text works or deconstructive works about dance. They were not really interested in cultivating any dynamics of the moving body specifically. My generation has somehow digested that, and is now responding to it: we’re coming at things conceptually, but we’re trying to pair it with a very rich and embodied approach to the body. Things like virtuosity, style, and aesthetic are no longer dirty words in dance. That’s really what I’m interested in, and what my work is moving towards.

You’ve been doing choreographic services since 2013, as well as conceiving pieces for the theatre. How do those two relate?

Fundamentally, they just have two very different histories and architectures. At the heart of my work are questions about how physical and verbal languages intersect each other: how they are valued or exploited, and what the conditions for them are. That’s always at the root of my work, whether it’s in the theatre or in the format of services. In the theatre, I can treat the experience of viewing choreography differently: I can stage it, I can deal with a very sculpted singular perspective, I can treat time differently. There’s a different kind of social contract in the theatre. The services are really about zeroing in on distilled singular aspects of choreography.

Do you ever feel like you need to adhere strictly to a particular dance style?

No, I definitely don’t feel like I need to or can. Like, I’m obviously an accomplished dancer, but I’m not a professional popper. I’m really interested in all styles and what denotes a language, or how a particular form can be used for a particular work. I’m always somehow re-skilling, bringing in new tools into my work, having them come back and inform me. In the contract [signed with the ICA] I call this form adagio popping, because Fran [Chiaverini] and I bring this very controlled, agile thing to it — traditional popping is very tricky and flashy. We bring a much more fluid approach to it, which I think comes from the history our bodies have.

What about when you throw speech into the context of dance? How is that language different?

I’m particularly interested for my work to unfold this right-brain/left-brain dichotomy — the analytic versus the expressive. I love this idea of finding forms or situations in which the body is vocalizing whilst moving, and how they’re kind of riding each other. I think this work really distills that. I think that we’re so navigated — not only in cultural production, but in culture at large — by language. It’s such a strict, codified, preordained force in Western civilization. So what do you do with it? Meeting this language with the body is my way of softening those edges, to make these languages look back at each other. The visceral quality of seeing a moving body has an effect on the language that you’re hearing. I like that in the piece the eye loses itself in the moving body, but is then suddenly brought back by me repeating, “Who’s hiring? Who’s buying? Who’s servicing who?”

Have you ever been hired for just one hour?

Once, I did just two hours. But I don’t do that anymore. I try to reap a longer commitment from the institution or client. There was one instance where I did Some Cleaning in the office of a private collector. There was just one person watching. But it wasn’t a lesser experience! Last night, there were 20 or 30 people in the space at all times, and that’s very different from this afternoon, where there were 2 people. I don’t think what affects the piece is so much the architecture or the status of the space. I think what changes most is how many people are viewing it at the time. There’s been some really enriching moments, where you’re just there with one person.

In the piece you ask rhetorically, “What are we getting out of this?” And reply, “You’d have to stick around for a while to figure out.” This piece can’t be archived, it can’t be collected. What are you achieving?

It’s a good question. In practical terms, the purpose is to live off my work, which is not yet entirely happening! It is a commodity, it is a service. I’m working and I’m getting paid for my work, but that’s just the practical aspect. Beyond that, I think I’m gaining a lot of experience. I learn a lot about my self, a lot about how to work with other people, how to be with other people. Since Tuesday, Fran and I got much better, which is one of the stipulations of the contract. The client who hires the service supports us gaining corporeal knowledge. It teaches me how to stick to something, how to be dedicated, how to be focused. And I have to say, there’s a spirituality in the time that I’ve spent with it. When it comes Sunday, Fran and I would have spent 27.5 hours doing this thing!

Credits

- Interview: JEPPE UGELVIG