FRED TURNER: Silicon Valley Thinks Politics Doesn’t Exist

|Nora Khan

Technology isn’t handed down to us by the gods. At 032c, we inspect the components of our digital reality, fully expecting to see ourselves reflected back. In this interview, excerpted from Rhizome’s Seven on Seven conference publication, What’s to be Done?, editor Nora Khan spoke to media theorist Fred Turner about the tech industry’s frontier puritanism, the myth of “neutrality,” and the idealist art on Facebook’s Menlo Park campus.

Fred Turner is widely considered one of the foremost intellectuals and experts on counterculture’s influence on the birth of the tech industry. He is the Harry and Normal Chandler Professor and Chair of the Department of Communication at Stanford University. He has written three books: The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (University of Chicago Press, 2013); From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (University of Chicago Press, 2006), and Echoes of Combat: The Vietnam War in American Memory (Anchor/Doubleday, 1996; 2nd ed., University of Minnesota Press, 2001). He is also a former journalist, writing for a range of publications from the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine to Nature.

Nora Khan: You’ve written at length on the New Communalists, their rejection of politics, their attempts to build a pure new world on the edge of society. This ethic was translated into tools, infrastructure, and material for the technological world we are in today.

But, as you’ve argued so well, that rejection of politics, embedded in tools, has given us a series of disasters. To me, it seems the most insidious effect is when this claim suggests more advanced technologies are apolitical, amoral, or neutral. It seems particularly absurd when you start talking about machine vision, predictive policing and their algorithmic phrenology, databases sorting people by their employability, or psychographic maps.

I often hear tech activists and critics decry technology companies’ claims that their tools and platforms are neutral. I also do the same. But where does this idea of technology as neutral, come from? Is it similar to how business leaders claim the market is amoral?

Fred Turner: Well, I’ll speculate, and I hope it’ll be useful speculation. There are a couple of sources. One is chronologically proximate, and one is probably a little bit more distant. The proximate one remains professional engineering culture and its educational system. Engineering education is a system in which explicitly political questions are generally relegated to other fields entirely: political science, sociology, history, English, and on down the line.

The practice of engineering is too often taught as if it were simply the design of functions, the design of things to do things. It’s sort of an explicit ethical choice, inside all parts of the field, to leave politics aside. (Although I think that’s changing.)

This means you’ll get people who tell you, “It’s not my business whether the bridge is good or bad. The bridge has to work. The bridge has to hold up.” That’s the goal. That whole tool orientation is a pragmatic, self-serving vision inside professional engineering training. It’s been there a long time.

There’s a deeper thing, that goes way, way back to the early modern period. It’s about where the seat of the government is. In the era of kings and queens, government resided in the body of the monarch. Technology was implement through which the monarch got the job done, but it was only an implement. The power to rule was was in the blood of the monarch.

Kings and queens would demonstrate their organic power by building automata and staging amazing mechanical expositions in their courts and gardens. Chandra Mukerji of UC San Diego has written a beautiful book on the Gardens of Versailles and how they were, essentially, models of royal power. But they became models of royal power when Louis XVI demonstrated technology. The power itself resided inside him. The political was the king, the inheritance, the social role around the king, the court. It was people. As we look through time, I think that idea of politics being people gradually morphed and became attached to the idea that politics could live in writing. Politics is what we say and do. Tools are, by definition, things that help us say and do that, but power is, itself, something deployed by living beings, in person eons ago and later through letters and printed proclamations.

Today, thanks to Marx and especially Foucault, we think about power and technology differently. It’s Foucault who teaches us about governmentality. More recently, most everyone in the academy on the social science side has had some encounter with the study of science and technology, particularly, actor-network theory in which it’s always a social actor.

There has been a whole lot of work bringing things back into the social world, and that’s just work that’s been done since Foucault, Bruno Latour, and all the different folks that they’ve worked with in the United States and Europe. The question of why technology is considered neutral is only possible because we’ve had that last two generations of scholarship.

The next thing you know, you’re deep in an Orwellian swamp.

NK: And it gets more tricky when such effort is invested into maintaining an image of the tool as neutral. Many of the engineers and narrative designers who are sitting in these rooms are perfectly aware that you are persuading someone to feel and think. The design of technology hides its political imperatives by presenting as neutral.

It seems the most accessible and powerful example of this is narrative and conversational design, mediated through bot and virtual assistants and interfaces. You have poets and playwrights who are brought on to write bots, creating soft and pliable brand personalities. Add to that psychologists, cognitive linguistics scholars, and of course, captologists, trained in the study of persuasive design – hey, a department based at Stanford! – channeling a carefully targeted design through interfaces.

FT: Here’s where you can see that wonderful migration of the material engineering position, a position born out of mechanical engineering, with physical engineering migrating into social engineering sort of unconsciously. It makes the migration by moving from thing, to text.

So, when an architect or a builder builds the building that constrains the behavior of the people in it, everybody’s happy; that’s the point. Building objects that constrain behavior in benevolent ways is what engineers do. It seems that way, I think, to many folks who imagine and think of themselves as engineers. (There’s a whole other question about whether programmers are, in fact, engineers.)

But if you take it seriously, that these are too, engineers, then the notion of moving from a physical architecture to a nudge architecture* isn’t such a big leap. The notion is that the option of benevolent influence through infrastructure, or team design, seems a pretty reasonable choice.

But of course, it isn’t, right? Because text and interfaces – interfaces being symbolic structures rather than material ones, although they have a material base – they work differently. They have different kinds of effects. They get inside us in different ways. If I have a material wall in a building and I just walk into it, it says, “Oops. Now it’s soft; can’t go that way.” “All right, no problem.” Nothing sort of inside me has really changed.

But a nudge infrastructure that changes my desire such that I desire a red Popsicle, not a green Popsicle – that’s different. Once it starts to change so that I desire a baby made with brown hair, because we need more babies with brown hair, what happens then? You can walk down that line very quickly.

The next thing you know, you’re deep in an Orwellian swamp. Engineers barely think about that swamp, because building architectures for benevolent influence is what they do.

NK: Relational AI is another swamp, building a mind that is mirroring our consumer desires back to us. It’s becoming more difficult to see this design, these tiny incremental micro-adjustments to interfaces and infrastructure. So how can the average person understand and track this process, especially when a company’s design thinking is proprietary, locked away in a black box? How is the average person to begin to demand ethical design or legible design? Other than, say, mining the brains of tech workers who abscond to activism, and tell us what’s going on inside.

FT: Oh my gosh. That’s the $60,000 question. You probably know Tristan Harris?**That’s one of the questions he’s trying to answer and I’m going to put my money on him. I don’t have an answer to that question, but I do have some comforting historical context to offer.

We are building these kind of mirror systems, these mirror minds, that reflect our desires, and then act on them. I think what’s different about them compared to historical examples isn’t the mirroring part, so much as the mode of interaction.

Everything that you just said about the AI, with the exception of how we interact with them, could’ve been said about the Sears Roebuck catalog in 1890. The Sears catalog was a desire analogy, a desire mirror that was carefully tweaked. The products were carefully removed and inserted to produce desires in people on the prairie and to give them means of satisfying those desires.

It also gave them the means of interacting with Sears as a company. What’s changed since then is the speed at which the interaction between the user and designer occurred, as it does now in virtually real time. The catalog had to be mailed out and read, and purchases had to be made. The speed was months and years. But people were as disturbed at the end of the 19th and in the early 20th centuries by the arrival of new kinds of media in those periods as we are about AI. Many of the fears that we have are very similar, the mirroring one being a leading one.

NK: On our survey, we asked a question about Openwater, a consumer wearables startup that’s trying to develop a ski cap to “read your mind,” using data about oxygenated blood flow to the brain to read desires, thoughts. This is a claim made by the founder, formerly of Facebook and Google (an expert engineer around holograms, high-pixelated screens), on stage at conferences. She calls this move toward mind reading inevitable, a statement made with total confidence, and very little irony or pause.

What is at play in some of the more possibly ethically dubious inventions in Silicon Valley? Is it a drive to own all human “territory,” inside the body and out? I also think of the archetype of the White Hat Hacker, the lone genius with access to code that no one understands, who knows what is best for society. The unknown may seem terrifying, he says, but you’ll soon see.

FT: I think that’s absolutely what’s at play. I was struck in the late ’90s and early aughts as some of these early systems were being built, but how many of my friends would say, “Oh, you worry too much. The good hackers will protect us. People will crack open those systems. We’ve all cracked open other things.” And that’s tremendously naïve. It’s part of a deep prejudice in American thought. Americans tend to think in terms of individuals. They tend to not think in terms of institutions.

One place that it happens is in how we read what we can do with technology. We think, “Sure, big systems may come along, but individual rebels always triumph.” That’s part of our deep cultural narrative. “And it’ll happen here, too.” It’s a way in which that same cultural narrative gets taken up by engineers – and you’ve just given me a fabulous example of that happening on stage – where these folks imagine themselves as the archetypal American frontierspeople. The nature of the frontier is to be conquered is irrelevant; it’s the conquering that matters. The actual westward push of Europeans stomped all over native peoples. Now, you see people like the founder you just described, quite happily, marching across our brain space as though it was just the latest in open, organic American fields to be conquered. We’re the natives in this story and that’s terrifying.

NK: The brain is just more material to examine and absorb. People are raw material. Code to be unlocked.

FT: Exactly. The brain is just another material. There’s a lot of deep American mythology at play. That declaration about wanting to read your mind: it is a classic case. One of the things I’m most interested in these days is the ways that technologists are thinking like the early American Puritans, who were my first intellectual love.

My idea of utopia is actually a hospital.

NK: There’s a lot in your “Don’t Be Evil” interview for LOGIC that I really enjoy, particularly your moments of reflection at Burning Man. You traced a line from this desert excess back to a more Puritan, deeply American idea of the restart.

There’s a religious zeal in wanting to restart society from zero. I visualize this in terms of the simulation. If you can build a world from scratch, you can also build a person without history or politics.

This seems optimistic until you realize that what some designers are hoping to get rid of are the more “troublesome” aspects, like race or gender or history. They are modular add-on features that can be removed. That is an ideology. It now drives social engineering and corporate-driven city planning and design. San Francisco is a good example.

FT: There’s long been a lot of traffic between urban designers and game designers, even before things got digital. I find that fascinating.

You are saying something that I want to pick up on, because I think it’s really important: this idea of building a person or a place without a history. I think that’s a deeply American idea, because we leave the known. We’re supposed to be the country that left Europe. We’re supposed to be the country that left the known.

Why did we leave the known? Well, so we could become the unknown, the people without history, the people without a past. When you leave history behind, the realm that you enter is not the realm of nothingness. It’s the realm of divine oversight, at least in American culture.

When the Pilgrims came to Massachusetts, they left the old world behind so as to be more visible to God. The landscape of New England would be an open stage and they would, under the eye of God, discover whether they were, in fact, the elect: chosen to go to Heaven after they died.

No technologists today would say they’re a Puritan, but that’s a pattern that we still see. We see people sort of leaving behind the known world of everyday life, bodies, and all the messiness that we have with bodies of race and politics, all the troubles that we have in society, to enter a kind of ethereal realm of engineering achievement, in which they will be rewarded as the Puritans were once rewarded, if they were elect, by wealth.

The Puritans believed that if God loved you enough to plan to take you to heaven in the end, he wasn’t going to leave you to suffer on this Earth before you came to him. Instead he would tend to make you wealthy. Puritans came to see that as a great reward. Puritans, and broad Protestant logic, deems that God rewards those whom he loves on Earth as in Heaven.

You can see that in the West a lot now. Folks who leave behind the social world of politics and are rewarded with money are, in fact, living out a deep, New England Puritan dream.

NK: The city on a hill. The early settlers on it, looking down at the wilderness, mapping civilization. This idea of having a God’s eye view of society maps a bit onto building of the simulation or the model. Being a worldbuilder means you can position yourself as neutral, as the origin, which is an amoral, evasive point which you can never really capture. It vanishes.

But there are a remarkable amount of coders and programmers thinking in terms of ethical design who want to help us visualize a world with history and politics. Do you think ethical design could help us do that? Is that an imperative that is useful now?

FT: I think everything helps. I think that what we like to call ethical design – well, you have to think very hard about whose ethics are built into the system, and how people have agency around that. This is an old lesson in science and technology studies, that if you build a road that only accommodates cars, then only people with cars will be able to ride on it. You may value independence, and you may see that as an ethical choice, but it may be that some people don’t even have access to that ethical framework because of the kinds of lives they lead on the material plane. And then, you’re stuck.

I’ve always found it very hard to think about any system, any planned, top-down system as, by definition, benevolent. The best systems and institutions are constantly focused on negotiation, on structured negotiation. So, the best institutions are places that have a constant system of check and balances.

My idea of utopia is actually a hospital. [Laughs] A hospital is a place where people get together, work very hard over very long periods of time in defined roles, checking and rechecking each other’s work, and they work toward a benevolent goal of saving lives. If you were to build a society built along similar lines, hopefully not one where everybody wears scrubs and white jackets, that starts to be a better place. So, the building is architected, so the systems are architected, but the negotiation is constant. That’s what I’d like to see.

NK: That’s lovely. I think of how Kiyoshi Izumi redesigned psychiatric wards in Canada after dropping acid. The caged-in architecture, the lack of privacy, of clocks, the barred, high windows like a prison; Izumi felt how distressing and inhumane it was. The ideal mental hospital valued privacy; patients had sound proof rooms with unbarred windows. Sources of perceptual distortions, like silhouettes, terrifying to someone with mental illness. Patients had less distress in this communal space driven by a different set of ethics, one more compassionate.

FT: I want to riff on that for a second. If we go back to that question of these neutral worlds, if you act like a God and build a world that doesn’t take account of differences, but rather tries to neutralize them in a single process, or a single code system, or under a single ethical rubric, what you end up doing is erasing precisely the kinds of differences that need to be negotiated.

So, it may look like a benevolent system to you. In fact, a form of a truly benevolent system is one that, I think, allows people to negotiate the distribution of resources across differences. That’s a very difficult problem politically. That’s what politics are for. You can help with those negotiations. If you can help people work with those who are different from themselves, you’re better off.

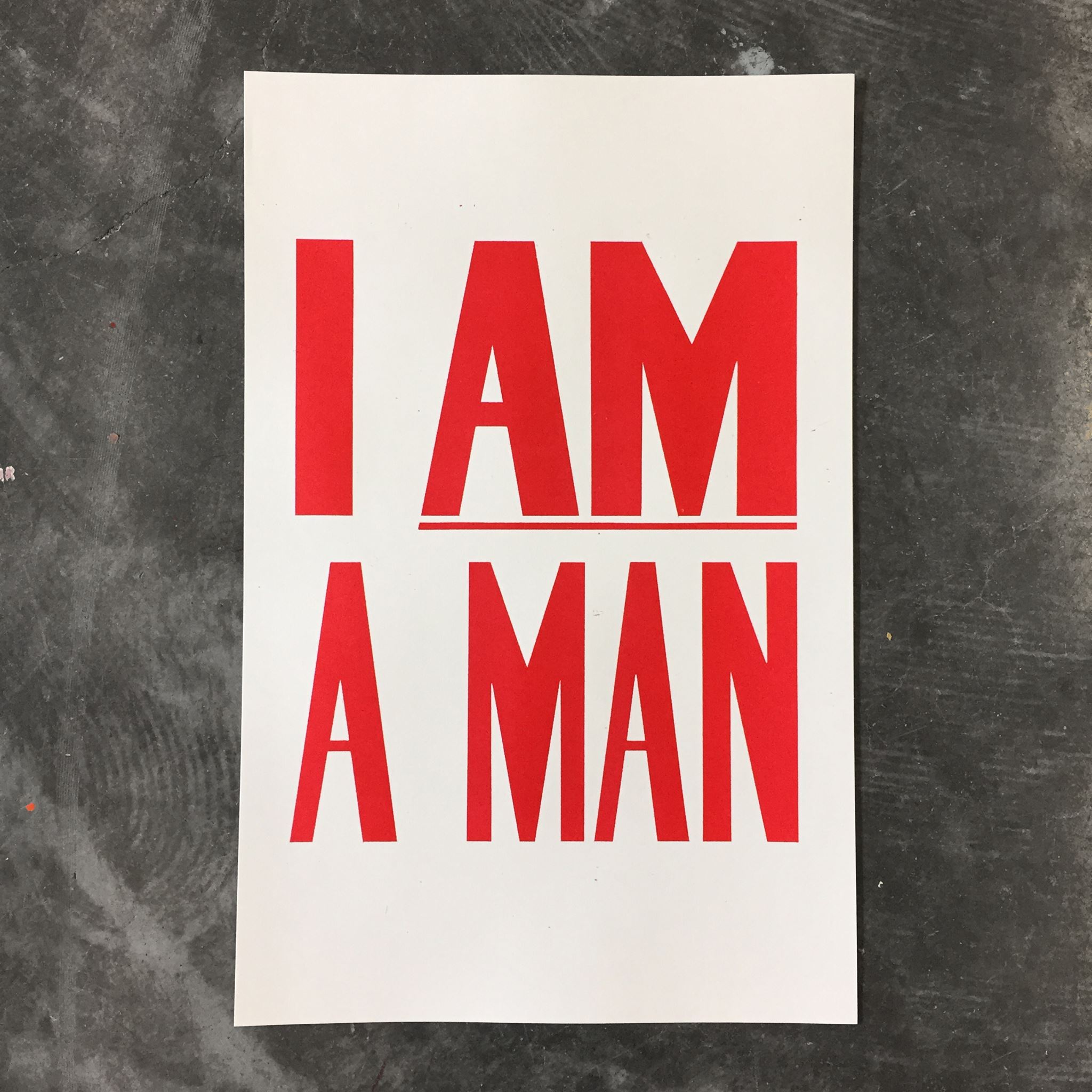

NK: And this seems even more difficult to accomplish when diversity and identity politics are embedded in corporate marketing. I’d like to talk about your new piece on the aesthetics of Facebook, on the play at diversity and identity politics without ethical follow-through. There’s a perverse contrast between the poster at their Menlo Park headquarters asking visitors to “Take Care of Muslim/Black/Women and Femmes/Queer Latinx …” and so on, when there are no unions in sight. I’m guessing the hiring process would suggest some realities that are not quite aligned.

What is the danger in this flattening, this validation of diversity as a cover for violation? The image of counterculture, progress, transformation – these are very seductive images to imagine oneself embodying. How are people to stay alert to the difference between iconography and action?

FT: We’ve done it differently in different eras. There was a lot of work to help people resist propaganda in the ’30s and ’40s. There were whole institutions formed to do that. There was a lot of work to help people resist the rise of commercialism in the ’20s.

But something has changed since then: Individualism and attention to identity are sources of elite power right now. Facebook’s mission is entirely consonant with identity politics. It precisely helped people break apart identities and become even more factional in identity. They give clear terms for this expression, they just market those expressions back. In those kinds of differences are exactly the kinds of market segments that matter to them, the segments that Facebook wants to monetize.

The focus on identity is one of the keys, I think, to being an elite American these days. That’s part of where you see the backlash in the South of Trumpism. When we focus on identity, we focus on different modes, what you’re describing, rightly, of market segmentation.

What we lose track of is just raw poverty. Modes of separating that are geographically-based, modes of separating that are age-based, modes of separating that have absolutely nothing to do with our race, our gender, or our ability to express our identity diversity. Those are all important issues. I don’t mean to knock those at all, but to the extent that elite Americans focus on identity diversity and look to that as a way to make solutions to the problems they’re seeing – they’re going to get stuck.

The way that we fix a Facebook is not by learning to read its representations more effectively. It’s by using the democratic institutions that we have. We have to recognize that it’s a company, not a system of conversation, but a for-profit firm, and then subject that for-profit firm to precisely the kinds of regulation from the state, elected by the people, that we apply to car companies, to architects, all the other industrial forces in our lives.

We have to recognize that Facebook isn’t special. Weirdly, to do that, we have to start recognizing that identity itself is not special and above the political fray. We need to do our politics through institutions. We need to return to that old, boring style of recognizing differences and negotiating across across them.

NK: It’s the core setup of neoliberalism. You find many First-Generation immigrants who are leftists or socialists have great, serious critique of neoliberal identity politics. This position isn’t the same as not valuing the expression of identity; it’s a critique of how the expression of identity alone syncs so well with the financial imperative of platforms.

I don’t see identity politics addressing the real material issues of our time, like how racial capitalism intersects with city planning. I see perfectly expressed identities in fiefdoms, without any politics on which we can agree, or a space in between in which we can gather together to effect material change.

FT: Yes. That’s exactly right. Facebook’s power blew me away. The poster that bothered me the most in Facebook was a poster of Dolores Huerta, who was an organizer of the farm workers. She’s still alive. You’ll know that she was one of America’s greatest union organizers in the 20th century. And Facebook is a company that has relentlessly resisted unionization.

Some of its contract workers are unionized, but that’s it. So, you have to wonder, why is a company not just tolerating, but promoting the image of Dolores Huerta around its place? Part of the answer, on the part of the designers, is trying to help workers appreciate that there’s a diverse world out there, and they need to be in touch with it. Fair enough.

But I think that a poster of Dolores Huerta only works inside Facebook if nobody remembers what it was that made her Dolores Huerta. So long as you can turn her into an image, particularly, a Latina female image inside of a firm with a dearth of Latina females, you sort of check that expressive political box, then carefully uncheck the institutional box of unionization or making institutional change, that would actually distribute resources to the communities she represents.

NK: It’s unbelievable. As long as her image means nothing in particular, then it means just as much as any other image.

So then, this support for full expression overlaps very neatly with support for “unfettered creativity” and experimentation, so, art. Who wants to get in the way of people living their passions? Art’s status as an unarguable public good, makes it a powerful space for pushing ideology.

FT: Oh, very definitely.

NK: Without tipping into institutional critique, how does this ideology of creativity, at all costs, change the kind of risky, experimental, challenging art that can be made?

FT: Let me address the issue of creativity. Certainly, inside Facebook, one of the reasons that they have art everywhere is, I think, to remind programmers and engineers to think of themselves as creative people. Ever since the Romantics, the creative individual has been an American icon.

But the kind of creativity that’s never gotten any attention is working class creativity. Do you know how creative you have to be to be a single mother with a below-poverty-level income, intermittent access to food stamps and food, some job or no job, and be able to make a living, and make a family stay together?

That’s the kind of creativity, the kind of MacGyvering, that engineers just never think about. It’s not even on our radar with regard to creativity. We talk about the ideology of creativity, and what we’re talking about is an elite theme, an elite hope that we engineers, we who architect this new surveillance reality are, in fact, the descendants of Walt Whitman, the descendants of the artists in the 19th century, descendants of American romantics. That’s just hooey.

In the meantime, as we pursue that vision, we very carefully elide all the modes of creative action and interaction that sustain people who don’t have the resources that we have.

Notice the language I’m using. I’m very carefully not using identity-based markers for those people because what matters is their economic standing or their regional location, the fact that they may be the children of woodsmen, who can’t move anymore because the logging industry is dead. These are folks who are living lives below the poverty line, in sort of post-industrial spaces that don’t look like Silicon Valley, and there’s some of them living in Silicon Valley. The whole rhetoric of creativity explicitly ignores them. It says to be creative is to build media goods that generate a profit and to have fun doing it. Bah! [Laughs]

I absolutely think that art and tech can go together and can help produce art that will, in time, will eventually be seen as being as beautiful, as valuable, as the Michelangelo paintings were seen by the Church.

NK: It is totally destructive to critical thinking. Creativity is for making media goods; criticism is in this way threatened by the ethic of technology and engineering, which demands we produce sense, or consumable, working ideological products. But successful art might be, sometimes, useless, or critical of labor. Actual dissent, not just an aesthetic of dissent.

How do you see “Silicon Values,” as critic Mike Pepi writes, shaping our relationship to art? He describes how art is deployed as a vital tool through which to push technological business models.

FT: Let’s step back and ask, what is tech, in regard to art? One answer is that the tech industry can be the sponsor of art. In that sense, it’s a lot like the Catholic church. When you ask me about artists at Facebook or artists at large companies or artists working with technologists, I think about the many generations of artists who worked with the Catholic Church from the early Middle Ages on.

Now, the Church is a complex institution. It has been the home of the Inquisition and its leaders have ignored and even hidden acts of child abuse around the globe. Yet the Vatican is also the place where Michelangelo paints the Sistine Chapel. The beauty of the Sistine Chapel, or of Michelangelo’s paintings, are not reduced by their appearing under the sponsorship of the Church. The best art, I think, can outlive the circumstances of its creation.

I think we also sometimes imagine that art is immune to the forces that drive every other thing that we do. It’s immune to commerce. It’s immune to greed. It’s immune to failure. It’s immune to ugliness. It’s immune to collective pressures. It’s always the product of an individual mind. The hope that we could have an art that would be outside the industrial world which is so clearly driven by tech, is a little naïve.

That said, I’ve seen art inside Facebook that has dazzled my sensorium. Truly. I’ve seen art using and leveraging devices created by people in Silicon Valley at places like the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and marveled at the beauty and the way that it makes me rethink what the natural world might be.

So, I absolutely think that art and tech can go together and can help produce art that will, in time, will eventually be seen as being as beautiful, as valuable, as the Michelangelo paintings were seen by the Church, or as landscapes sponsored by hideous patrons eons ago might be seen as beautiful today. I don’t think the sins of the sponsors necessarily ruin the experience of the art.

NK: And then there’s the second kind of art doing the support work, the oblique shilling.

FT: Yes. Art doing the work of tech legitimation. I hear, a lot of times, that we need to get artists and technologists together in some space, because the technologists will be able to show the artists their tools, and the artists will be able to adopt the tools to come up with creative new uses. The technologists will, in turn, be able to monetize those uses in terms of new products. This does, in fact, sometimes happen.

In the artist-technologist collaborations that I’ve looked at from the ’50s and ’60s, the work that went onwas primarily ideological. Collaboration helped everybody imagine that they were creative, that they were making something valuable. It made it possible for engineers who were building our media and communication systems, the Bell Labs sound system, or the engineers working at NASA on rocket engines that would send things into space, or people working in Silicon Valley on Polaris missiles, to imagine themselves as the same kind of exquisitely sensitive and culturally elite person that, say, a John Cage was, or Robert Rauschenberg was.

By the same token, Rauschenberg and Cage and others who collaborated with technologists in that period, were able to get new ideas, get money, and borrow some of the legitimacy of the engineers, who were winning the Cold War at the time. I think we see that now. I think we can see artists borrowing legitimacy of technologists, and then taking their money. We can see technologists borrowing the legitimacy of artists, and taking their ideas.

I think it’s a mutually beneficial relationship so far.

NK: At present, the Whole Earth Catalog, chaos magic, and mysticism, of the kind expounded on in Erik Davis’s Techgnosis, are seeing a strong resurgence within tech. It seems to me there’s a feeling that it is possible to go back to the original idea, that computers and platform can yet still mediums for liberation, rather than platforms for control.

So. What would a Whole Earth Catalog for our time look like, if we learned from past failures?

FT: Yeah. Hm. Oh, boy. Well, if you ask some of the people associated with the actual Whole Earth Catalog, which I’ve done, they will tell you it would look like Google. It would be a global system for an individual to search out the things that individual needed to build a life on their own terms. I think that’s fine.

But I think that definition misses the key part of the Catalog, which is the way that it didn’t actually sell goods. It printed recommendations for goods.

The recommendation letters came from people living on communes at a time when the only way know what communes were out there in the world, was to get on the telephone, or use snail mail letters. The Catalog become one of the first representations of the commune world. It was a map. Embedded in all those products was a map of all the different communes that were using and recommending them.

So, the thing that I would like to see, that I don’t think Google is, is a map, a kind of map of an alternative kind of society, a better kind of society. I don’t think the Whole Earth Catalogs mapped a better society, but they tried. Can we see a map of alternative communities, communities that are taking things in different directions, not just, can we search using digital tools for tools that help us lead our life the way we want to? I mean, that just sounds like the L.L. Bean catalog on steroids. Can we identify communities that are taking us in directions we want to, map their interconnections, and find some way for ourselves to search our way into new kind of community, and new kinds of institutions? I think that’s what I would like to see.

We have inherited from the Whole Earth Catalog a language of individuals, tools, and communities, which we’ve translated, I think, in tech speak, into individuals, communities, and networks.

There’s something I’ve always held against the Catalog, and that’s its individualism. The opening sentence, you remember, in the front of the book, is “We are as gods, and we might as well get good at it.” The sentiment, We are as gods, in the Catalog, meant that they were able to take the products of industrial society, and put them to work for individual purposes in what Stewart Brand called“a realm of intimate, personal power.”

To the extent that we imagine the politics take place in the intimate realm of personal power we’re going to get lost. We’re going to keep building interfaces that allow for expression, that allow for the extension of intimate personal power, and we’re going to precisely not do the work, the boring, tedious, structural work of building and sustaining institutions that allow for the negotiation of resource exchange across groups that may not like each other’s expressions at all.

So we have inherited from the Whole Earth Catalog a language of individuals, tools, and communities, which we’ve translated, I think, in tech speak, into individuals, communities, and networks. I would like to see a language of institutions, resources, and negotiation take its place.

NK: Beautiful. I’m going to go walk around in the woods and think about that.

FT: There’s another thing hiding in here, under the Catalog, an idea that the counterculture and neoliberalism share: if you just free people up and build a market structure, things take care of themselves. What this idea ignores is the persistence of subsidies, of regulation, of shared state resources, of things as basic as roads and bridges. If you don’t tend to that subsidy, you can’t have any of the other freedoms

So, that’s what we need. We need to be alert to sharing and sustaining our public resources.

NK: Artist Caroline Woolard speaks of this as a defiance of the academy’s teachings. This generation, she says in a recent Brooklyn Rail interview, is one of artists that makes cultural organizing, community arts, and advocacy a central part of artistic practice. To rebuild that degraded civic spirit, artists can’t be disengaged.

FT: Well, I think a lot about Eastern Europe during the Communist era and how artists dealt with that. Some artist became critical. Some artists became politically active. Other artists just wrote beautiful stories.

I do think there’s a role for disengaged art in a moment when otherwise our lives need to be engaged. I think there’s something to be said for laying aside objects of beauty for when times are better. I’ve spent the morning today at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin looking at early Renaissance paintings, filled with violence, but also stunningly beautiful.

Alongside these kind of political paintings, were all these little portraits that the artists did, just people’s faces from eons ago, totally disconnected from the politics of the time. They were just interested in the subjects’ physiognomy: their hair, their skin, their noses. Those faces come down to us as emblems of the kinds of connections we can make with each other across time that aren’t political in any direct, immediate, historically specific sense, but are the most deeply political in that they offer us a vision of seeing each other with love. That’s something that the arts can do almost uniquely, but they can only do it, in a weird way, when artists stand a little to the side of the political fray.

*Ed. – Nudge or choice architecture is a development of behavioral science, in which consumers are ‘nudged’ to make socially desirable choices, like eating better or recycling.

**Ed. – Harris is a former Google Design ethicist and founder of non-profit Time Well Spent, aiming for development of ethical design standards in tech.

This interview is excerpted from What’s to be done?, a limited-edition zine marking the 10th edition of Rhizome’s Seven on Seven. The publication was edited by Rhizome’s special projects editor Nora Khan, and designed by W+K’s Richard Turley, Justin Flood, and Frank DeRose. To purchase a copy, please email info@rhizome.org.

Credits

- Interview: Nora Khan

- Images: Facebook