Do We Want Anarchy Or Guerilla Warfare? Julian Klincewicz & RASSVET

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

“Do we want anarchy, or do we want guerrilla warfare? With the guerrillas in the forest, anarchy doesn’t achieve much, but guerrilla warfare can achieve revolution,” says Adrian Joffe, president of Comme des Garçons and Dover Street Market.

During the last Women’s Paris Fashion Week, I sat down for a roundtable with Joffe, founder of RASSVET Tolya Titaev, and artist Julian Klincewicz, on the occasion of Titaev and Klincewicz’s newly launched collaborative collection for RASSVET. The collection, which consists of denim, t-shirts, and eyewear, takes the poem/song “Oh Brother, I’ve Been Dreaming” as its starting point. As Joffe—who has known both Titaev and Klincewicz since the beginnings of their careers—joined, our conversation went beyond the specificities of the collection and opened questions around the general state of the creative industry. At what seems to be the peak of multi hyphenates and interdisciplinary work á la “I’m a DJ/artist/actor/singer,” we were asking if everyone can (and should) really do everything?

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: The main source of this collaboration is a poem and music piece that you made, Julian. Can you talk a bit about these two works and how they initiated the collaboration?

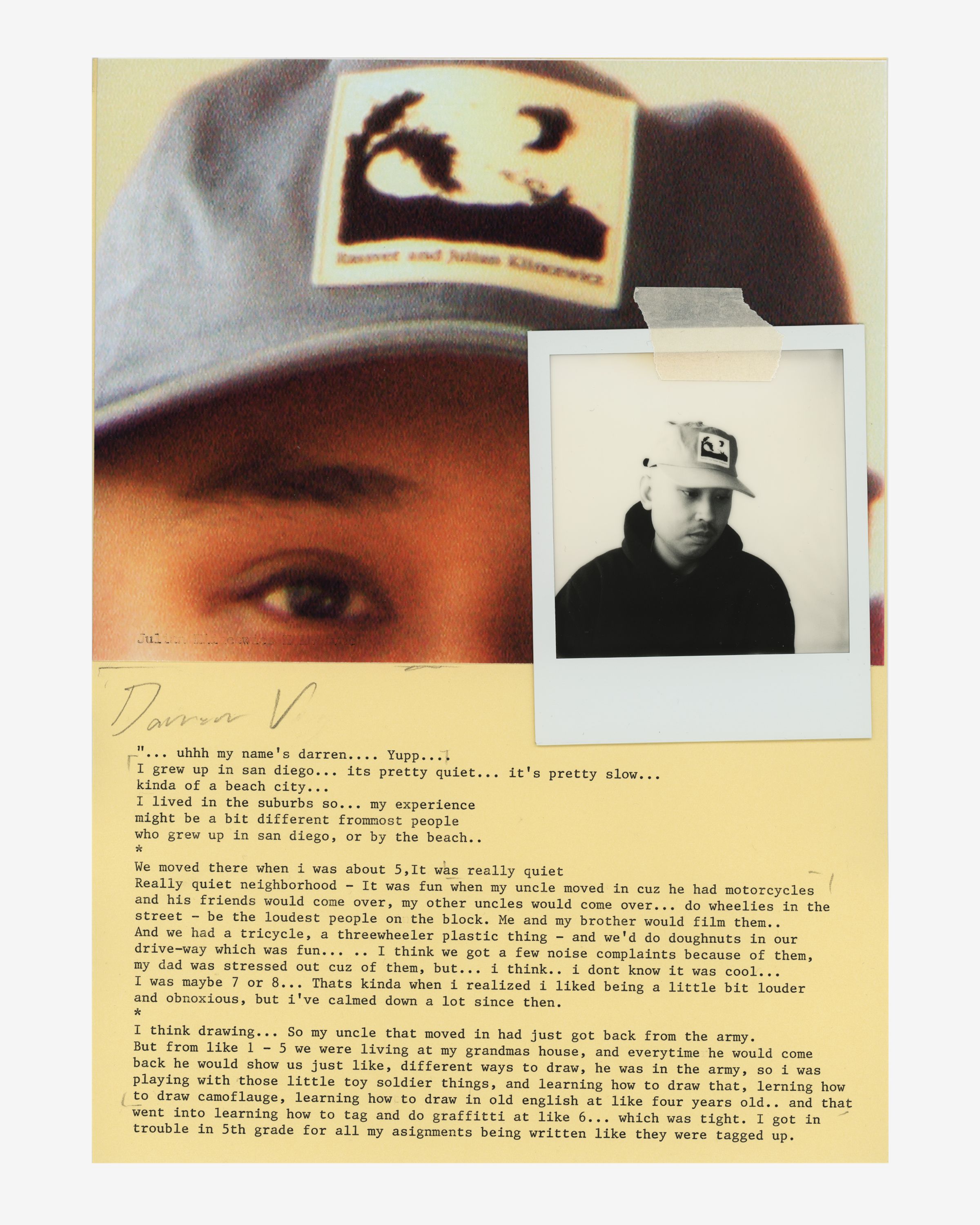

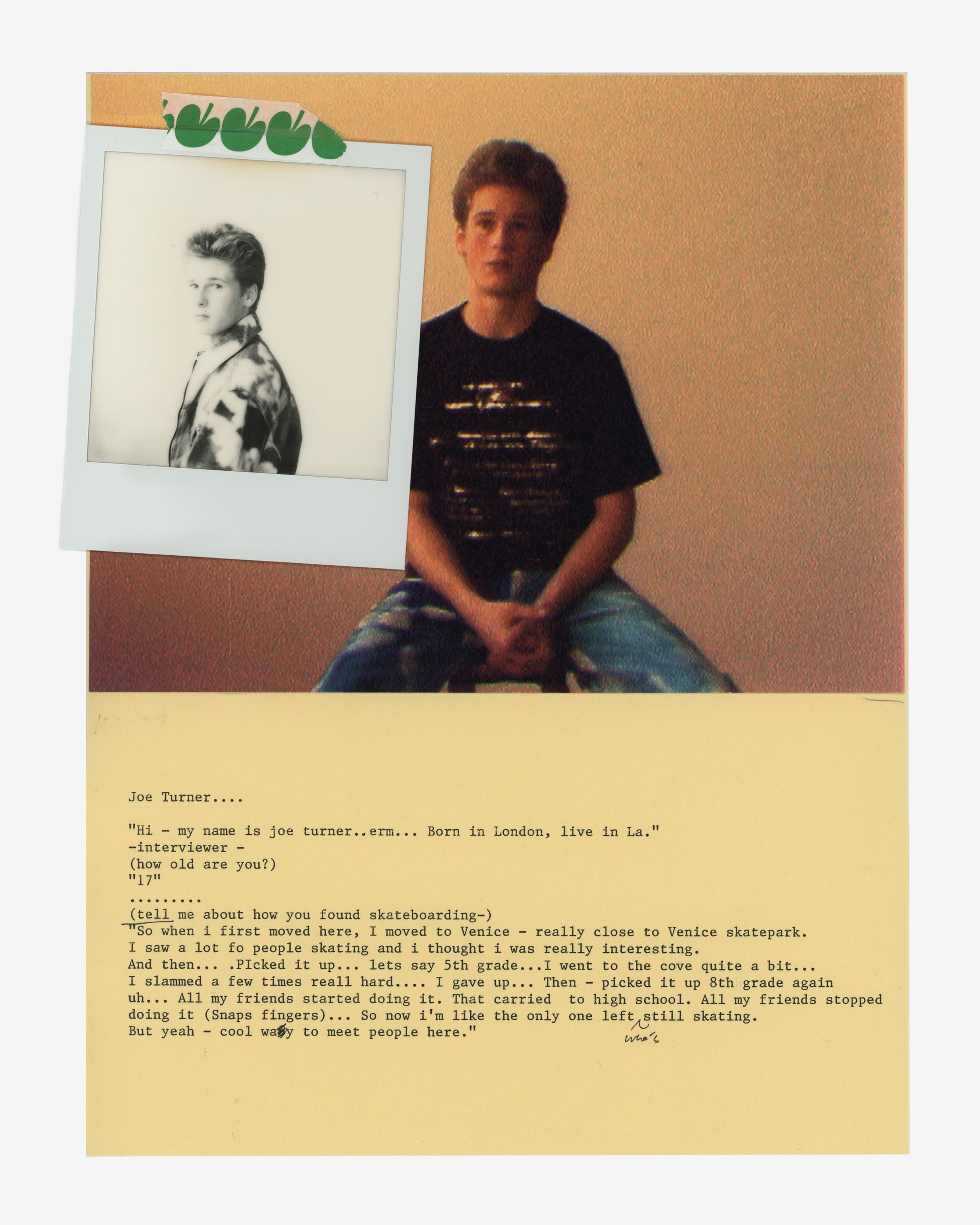

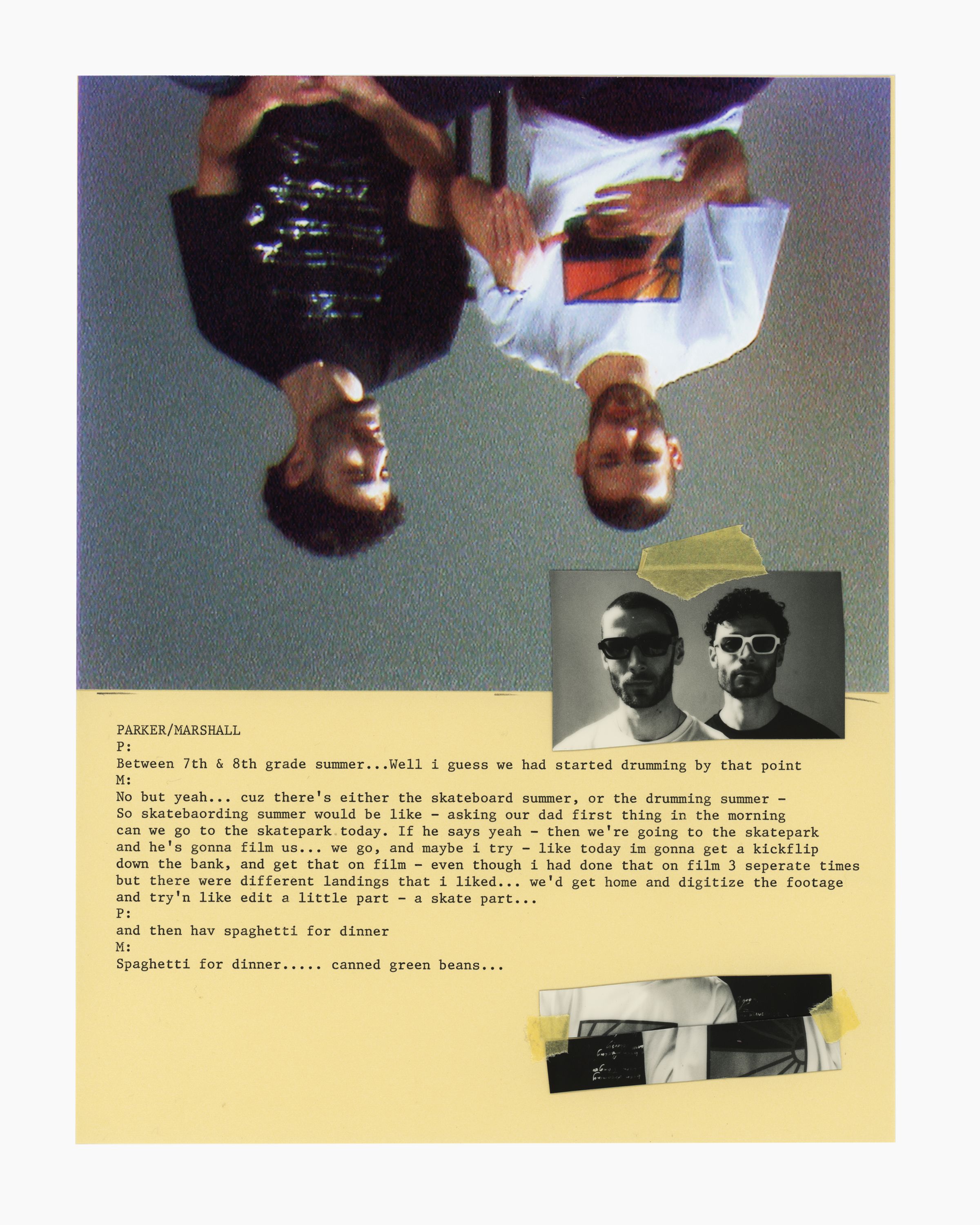

JULIAN KLINCEWICZ: Yeah, I’ve been slowly working on this poem/song called “Oh Brother, I’ve Been Dreaming,” which I started writing when I went to Lisbon a few years ago. I was filming a piece there with two 18- to 19-year-old boys and It reminded me a lot of when Tolya and I first met and of the intersection of skating and fashion.

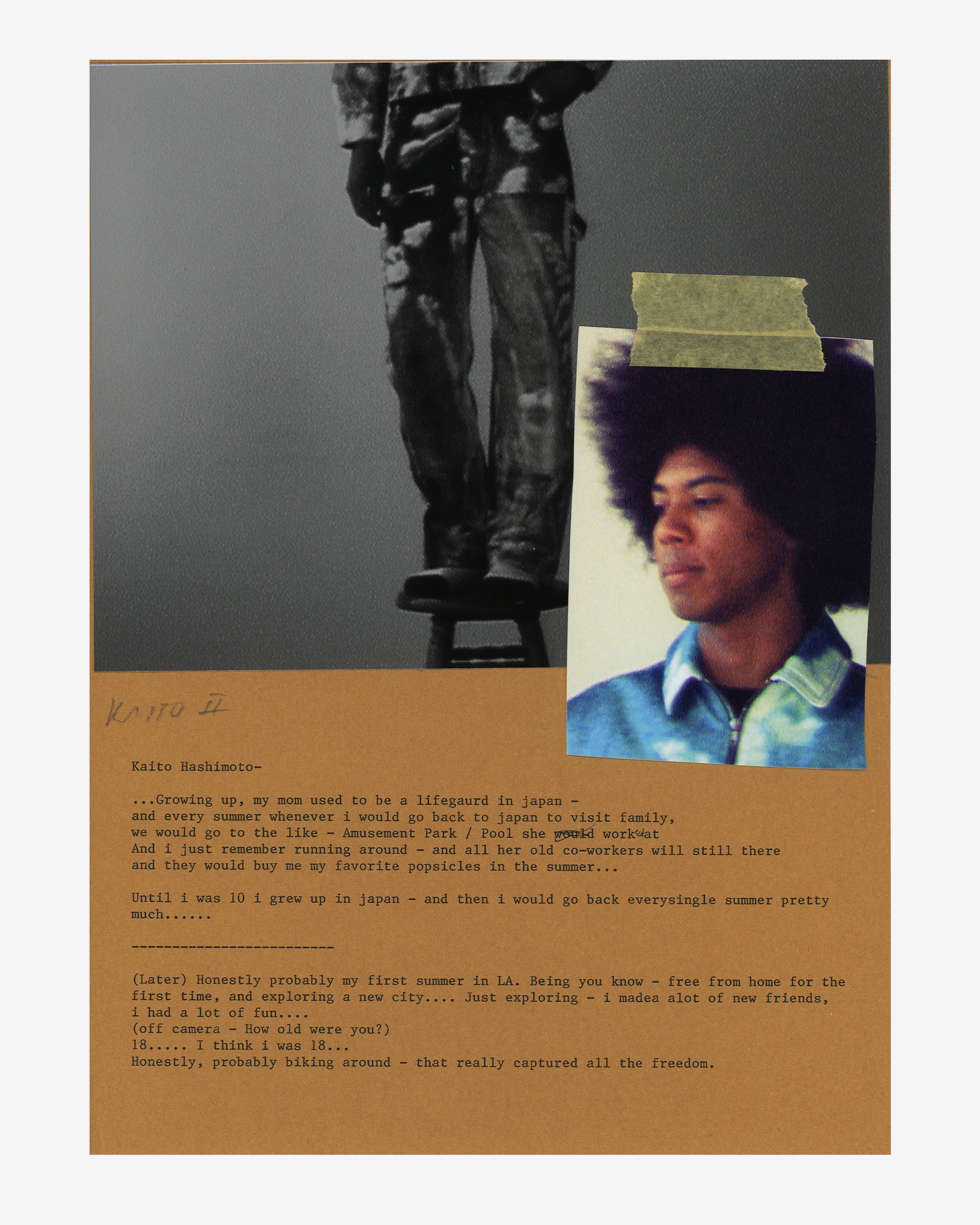

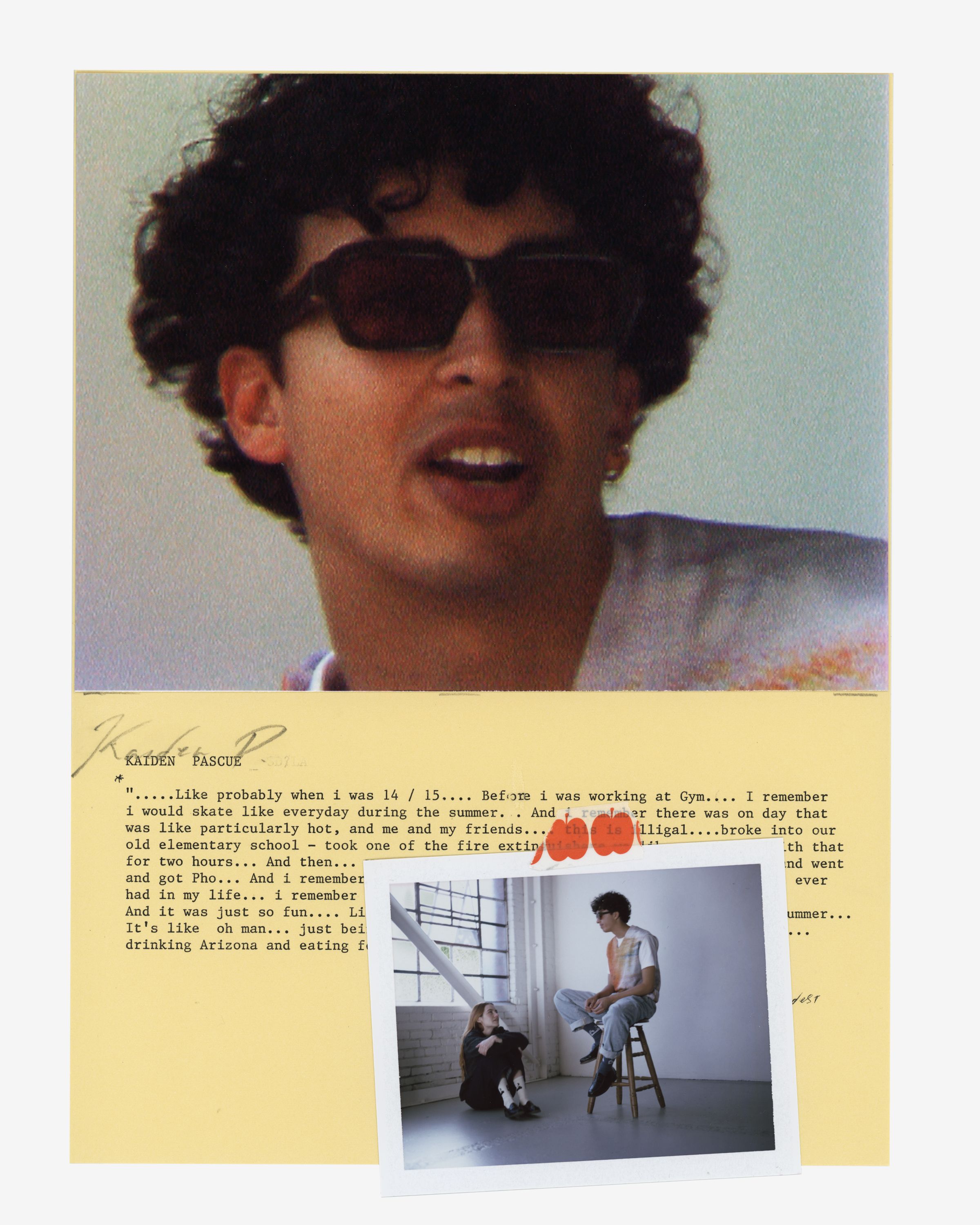

My first opportunities in fashion came from the Comme Des Garçons/DSM family and are also tied to skating and there’s always been some sort of tie between my fashion work and skateboarding. The poem/song wrestles with feelings of coming of age and of becoming slightly confused as you move through life. But then there are people who come back into your life to ground you, and I feel like Tolya has always been one of those people—someone who is very good at seeing the best parts of people and reminding them of them. I was thinking about being younger and skating, and about the perfect summer—all of that went into the song. That was around the same time Tolya reached out to do the collaboration. So, the whole collection revolves around this feeling of brotherly love.

CKE: How did you translate writing and sound into physical garments?

JK: For this collection, I started with the song and the feeling, and then Tolya sent images of my work that he liked. I had done this drawing of a tangerine, which reminded me of my summers with my Polish grandma when I was little in Michigan and there would always be fruit on the table. It felt like boyhood. And then I pulled a different image of a motorcycle blended with a wheat field. That felt like a visualization of a part of the poem. So, I approached the collection like a visual poem. Bringing together different elements into different parts of the collection. The whole collection for me is more like a body of artwork—the clothing illustrates feelings from the song. And the music in the campaign videos captures different feelings from the poem.

In general, I think about the starting point and connect as many dots as I can, trying to make a constellation. I think this process was quite collaborative. I designed some stuff, sent it to Tolya, and he would tweak it. Then we would work back and forth.

TOLYA TITAEV: On my end, the perspective is more on the shape we’re going to use or what we are currently developing that we can provide the artists to work on. This includes going through the archives and seeing what it can be. With Julian, it’s been hard, because there’s so much material to work with.

JK: We probably designed three collections worth.

CKE: From what you said, it sounds like community is a big part of your practice. This is also connected to the very present question in fashion whether to prioritize garments and craft or entertainment and community.

JK: Most of my projects in fashion have always been directly with people. The most important long-term collaboration I had was doing visuals for Virgil at Louis Vuitton. For me, Louis Vuitton was just a brand, but Virgil was a friend and a mentor. When we worked on projects for the campaigns, it didn’t feel like I was just trying to sell a handbag, it was more about building a world and telling emotional stories—and that was super meaningful. Since he passed away, I’ve still done a lot of fashion campaign work, but sometimes it can feel less meaningful without that truly personal connection. If creativity isn’t at the heart of it, it feels hollow. This project was really nice because I had been searching for the past couple of years for a new home with friends, brands, and a community where we’re on the same wavelength.

TT: My desire has always been to build a platform for skaters and artists to have a base to create from. We often collaborate with artists, friends, or people I personally know to create something for the collections. Doing a bigger collaboration with Julian felt natural.

ADRIAN JOFFE: It’s about synergy, when one and one makes more than two. There’s something added from the crossing of the borders and opening out to the community, where it’s not just the creative director getting somebody to do a job that’s going to sell more bags. Dover Street Market is about making a community that’s bigger than the shop. We’re not interested in just making a shop, getting things and selling things. We have to do things in a new way. Otherwise, there’s no progress. We're just repeating and repeating. Virgil was one of the leaders of that—he was multifaceted, he did so many things. I think it's the way people have to work—break out of their boundaries and collaborate with people to make something better.

CKE: From a business perspective, Adrian, it’s important to not only be a store but to also actively support brands and build the right audience—one that goes beyond customers—and host more artistic projects. At the same time, do you feel you have to prioritize the business part over, say, the artistic part?

AJ: I don’t think you have to. I don’t prioritize business. First comes creation and community, and then hopefully business will follow. Sometimes you have to think about it, because there’s no use doing things that have no business potential. But as for the community aspect, there’s this very building, which is going to be Dover Street Market Paris. We got it during COVID-19 and had three years where we couldn’t build the store. We did loads of things in this building, and it built a community even before we opened. So, fortuitously, it was great in a way—and we were lucky to have that time to build that community. The ultimate aim, of course, is to survive and grow and help more people—and help us. But it’s always a two-way street.

JK: Is that something that has always been natural? Or has it been a learning process?

AJ: It has always been a learning process. I didn’t know we would end up here. I’ve learned from Rei Kawakubo that it’s important to try and do things that people haven’t seen before. Without creation, you can’t have progress.

Once I was asked, “What’s your business strategy?” And I said, “My strategy is not having a strategy.” My strategy is: let’s see what happens. Be open to everything, and if it feels good, then do it.

JK: That feels like true creativity. To perpetually find ways to see things nakedly, to see things as what they are and what they can become and be open to the potential and the mystery that calls. Once you know what you’re doing, you’ve lost it. It becomes less interesting. I recently started a seashell collection and I have no idea why. Every day I look at it in my studio, and I’m like, “This is something.” What it is, I don’t know. What it will become, I don’t know. But it’s the mystery—this is the future. I fluctuate between thinking this is going to be huge and I’m a grandma.

TT: The same goes for when we’re starting a skateboard project with raw footage. You need to have the tricks in there, but then you start to think, “What will be the message?” What do you want to show? What’s going to be in this video? When you’re starting it, you don’t know how it’s going to come together.

CKE: I think that especially looking at young brands, the point at which many of them are struggling is when it comes to building a business strategy, having a financial plan. Even if your collections are exceptionally good, that’s what you need to reach the next step. Can you explain your idea around not having a strategy, Adrian?

AJ: The strategy is no strategy doesn’t mean there’s no idea. The most important thing is that you have a vision and work hard. I don’t think that it’s going to be overnight, it takes time. I guess that’s a strategy, but it's not like, how you're going to make lots of money. And then when it comes to selling and more concrete stuff, I can help with that. We have shops, and we get different people to come. But that's not exactly a strategy, is it? It's just like hints and help.

CKE: All your work is quite multidisciplinary, Julian. It reflects working modes of the culture industry that are extremely hybrid and probably becoming even more hybrid. Would you say this kind of intersectional work is something that came naturally?

JK: My natural go-to is very maximalist. I think I’m very much a product of our times. I am very multi-hyphenate, and at the end of the day, it’s about organic evolution with the people around you. 80 percent of that is chance. You make the best work you can and hopefully it aligns with people who can see your work for what it is or who see you clearly and you can connect with.

I’ve had a lot of amazing mentors. I had mentors in high school who were painters, and after that I had fashion designers and musicians as mentors. I’ve gotten to work with some of my favorite artists and see their processes and how varied there are. The one thing that feels really consistent is intuition and love of the creative process.

The one caveat is that I’ve also been really encouraged. They say all children are artists, right? Then a child shows a natural talent for painting and everyone’s like, “Oh, you’re a painter.” This limits the creativity. Looking back, I was really privileged and lucky that when I was little, I would draw, run around, make music, and take photos, and no one was like, “You’re this or that.” I was encouraged to do all of it—that sort of stuck as the baseline.

CKE: Then, at a later stage in life, you’re kind of forced to professionalize your work and yourself. Do you think this hybridity of the culture industry is always something positive? Different communities come together, but, at the same time, it potentially blurs the terms a bit. Who’s an artist, a curator, a photographer? Would you also look at this critically?

TT: I think it’s a great thing. Only positive.

JK: I love the phrase, “It takes all kinds.” You need everything, you need everyone, and you need the cross-pollination. Streamlining things is a capitalist construct.

AJ: I think that what you mean is that there are no more “kinds of artists” because everybody is doing everything. Is that a problem? Eventually it will be a problem if everybody does everything.

CKE: I think it is, in a way. For instance, the term “curator” is being used for everything—people “curate” their Instagram feeds. But this is not the same thing as curators who work for museums, have studied for years, and have built close relationships to artists.

AJ: There’s a danger when everybody thinks they can do everything.

JK: I think the danger is thinking you know everything but only have a little experience. Everyone could be a photographer, and I think that potential is amazing. The danger is the lack of discipline. You need the humility to study, understand, and really spend time to absorb everything until it’s so personal that you know it in an intimate way.

AJ: I think we saw this in fashion journalism when blogging came out. There used to be very good writers in the 80s and 90s. Fashion journalists studied fashion, went to school, and studied writing, and they could write beautifully.

TT: There needs to be time, dedication, and learning.

AJ: I think that there should be somebody in control who says, “Okay, you can do everything, and you can’t.” Do we want anarchy, or do we want guerrilla warfare? I think guerrilla warfare is good. We need rules and regulations. With the guerrillas in the forest, anarchy doesn't achieve much, but guerrilla warfare can achieve revolution. What do you think of that?

JK: I have to chew on that [laughs]. I’m thinking of phrases such as, “Jack of all trades, master of none.”

AJ: That’s what people used to say, but I don’t know if you can be a master of all. I mean you are in a way, Julian. Nobody should ever have put limits on you. And you're lucky that no one did. But not everybody should think they can do everything.

JK: I guess it’s experimentation. I felt a huge crisis of faith in art. That’s the feeling I return to every time. I think I can make meaningful things that will connect with people. And then you make the thing, and you’re like, “Oh, my god, no one's going to like this.” It's that crisis of faith where you’re perpetually skirting the line between thinking it's everything and nothing.

AJ: Is it important that what you do is liked by somebody?

JK: No, but as an artist, I want to connect with people and have a dialogue. That can happen through like or dislike.

CKE: Where do you see this hybrid culture industry heading? Boundaries between different sectors are already dissolving, will it just be one big haze in the end?

JK: I think you’ll have people going back to craftsmanship that is very specialized because it’s going to become a rare commodity as things become more digital and accessible. Simultaneously, I think you’ll have another reality where it will be quite commonplace for everyone to do everything—as such, this will no longer feel special. And once that becomes ubiquitous, then people will go back to specialization.

TT: At certain stages, it feels like there’s never going to be anything new or anywhere where things can go. And then, after years, things keep going and going. For instance, we’ve been talking about skateboarding with Julian. And for some time, it felt like everything had already been done. But now it’s very different. It’s the way you’re looking, the way you’re skating.

AJ: I think you’re right. It’s all cyclical. There are Dark Ages and there are Renaissances. We’re in a Dark Age. You have to believe it’s going to get better. You have to have good faith and do your best to bring in more light.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

- Photography and Video: JULIAN KLINCEWICZ

Related Content

This Means DAWN: PACCBET Skate Film in Los Angeles

JULIAN KLINCEWICZ: The Wunderkind, All Grown Up

JAMES BLAKE Seeks A Higher Vibration

CAN IT SKATE?: Skateboarding’s History of Cannibalizing the Footwear Market

ABC of CdG

ROLE MODEL: JOHN WATERS on REI KAWAKUBO

VIRGIL ABLOH: “Duchamp is my Lawyer”

GOSHA RUBCHINSKIY