“Once the Needle Goes In, It Never Comes Out”: LARRY CLARK on Sale in London

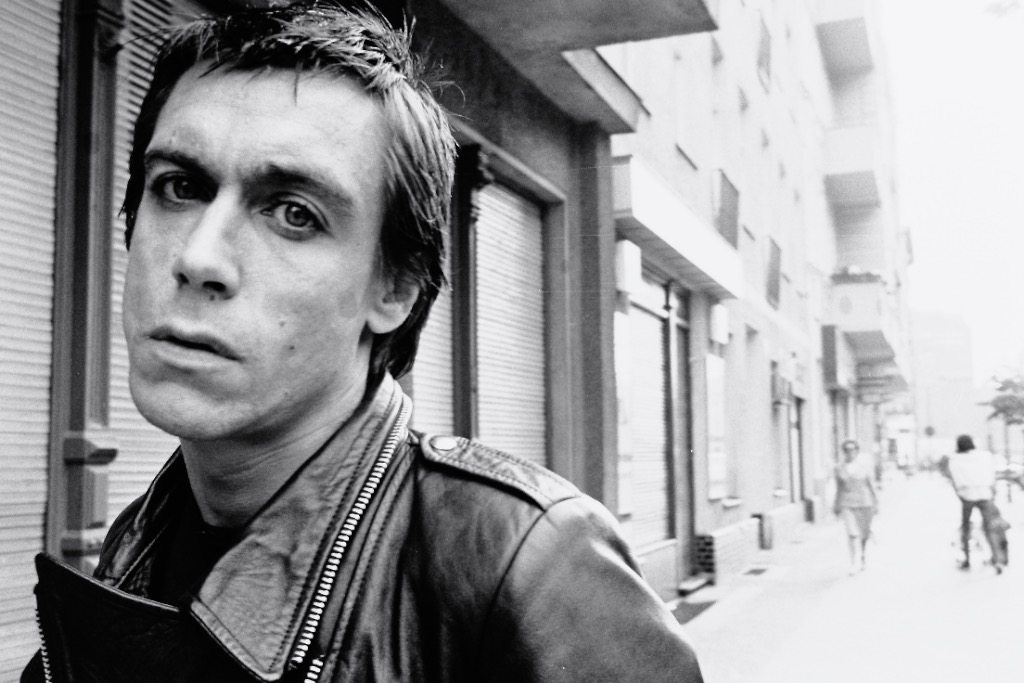

From July 1-6th, London’s Simon Lee Gallery is shedding a new light on the photographic legacy of Larry Clark, the artist and director largely responsible for the contemporary image of adolescence.

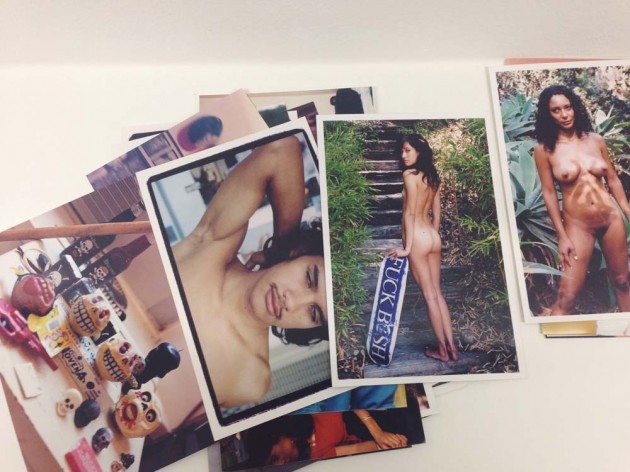

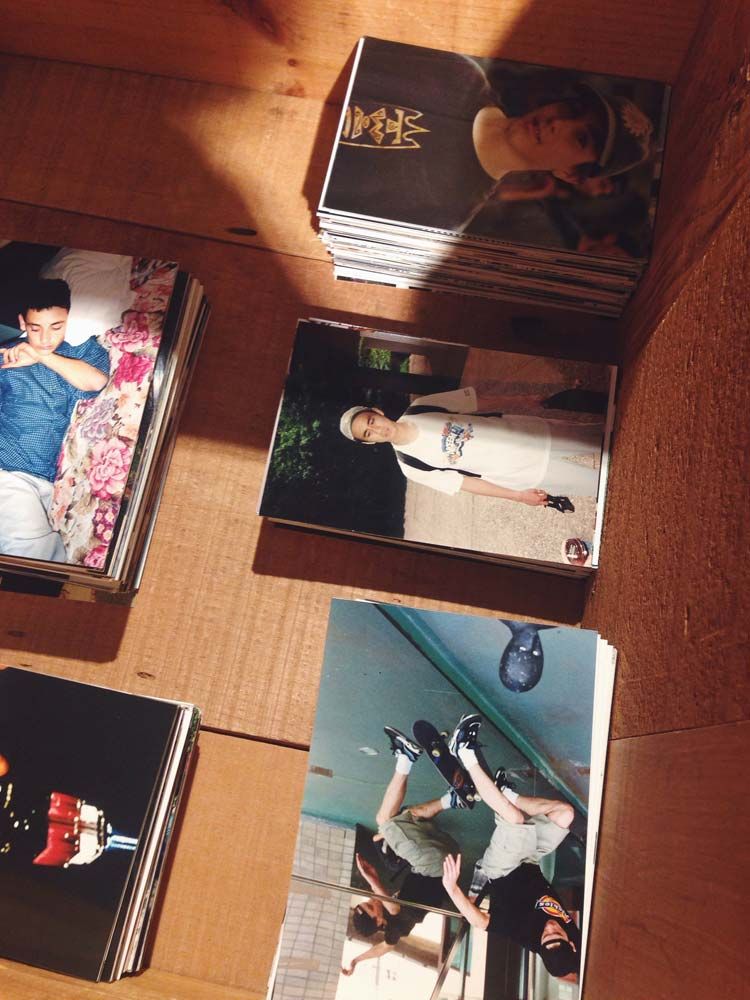

After a considerable amount of time in the queue outside the gallery, the doors open to a white space in the gallery’s basement. Inside a banged-up crate, Larry Clark’s photographs are piled in neat stacks. The images, shot between 1992 and 2010, largely feature Clark’s extensive family of friends and collaborators, skaters, muses, and kids.

The photos are classic Clark – skaters on a small town street, palm trees in LA, a girl under the night sky bursting with fireworks in New York, empty basketball ground under flat blue sky, legs, kisses, sneakers, an opium pill, a naked teenage couple. There are recurring narratives: numerous portraits of Tiffany Limos who starred in Ken Park and Jonathan Velasquez from Wassup Rockers, lots of naked girls from Supreme campaign, Clark’s self-portraits, often blurry, yellowish, and dozens of kids, depicted in transition from childhood to puberty.

One of young guys at the sale is particularly desperate. Wearing a bandana and black running shoes, silver earrings, heavy rings on his fingers, he’s torn between two portraits: a smiling kid brushing his dark hair back and a surfer-looking guy in a white T-shirt. “That one looks like a Gap commercial!” someone shouts. Or maybe Gap commercials just look like early Larry Clark these days. When I see the guy outside I ask which one he got. “Both”, he says. “I couldn’t separate them.”

Clark’s career as photography’s outlaw and prophet started in 1971 when he published the now iconic book Tulsa. “When I was 16, I started shooting amphetamine. I shot with my friends every day for three years and then left town, but I’ve gone back through the years. Once the needle goes in, it never comes out,” he wrote in the introduction. In its brutally honest depiction of teenage sex, violence, and drug abuse, Clark captured the black hole of the small Oklahoma town with the tender affection of an insider. Clark’s second book, Teenage Lust, came out in 1983. Completed while addicted to heroin, it featured images of Times Square hustlers, a decade before the dawn of the New York AIDS epidemic.

With the archive sale, Larry Clark is giving the kids at Simon Lee Gallery more than just a huge purchase discount. He’s giving them an unforgettable experience of joy and frustration, at the visual speed of the new generation – look through 500 pictures in 15 minutes, read the images, relate, fall in love, cherish, or reject it, and finally choose one to spend their hundred on. All the while questioning their own choices, hesitating in their attempts to narrow the selection down one by one.

Today, Larry Clark is 71, vegan, and sleeps 4 hours a day. He doesn’t skate anymore, but he still hangs around skate kids (and vice-versa). His latest film, The Smell Of Us, features a gang of young Parisian skaters and is due out this year. In the meantime, he keeps busy filming the second part of his Marfa Girl trilogy in Texas. Tulsa and Teenage Lust are currently on show at Foam Photography Museum in Amsterdam. Clark’s legacy is larger than life, and no small source of anxiety for the director. (In an interview before his opening at Foam, Clark expressed his fears of dealing with the back catalog of work he never had the time to deal with). The print sale could be one of the ways to deal both with the fear and the amount of material: outsource the archives to his devoted followers. In introducing his audience to the painful process of editing, he’s exposed himself as an artist like never before, and created a new level intimacy with his audience, all in the mundane form of a 10 x 15 photograph.