I Like Being an Amateur: Dennis Buck

|Claire Koron Elat

Dennis Buck, Photo: Nils Müller

In his latest body of work, Dennis Buck invites viewers into a world where meaning isn’t read—it’s felt. Moving away from sculptural interventions and toward a tactile, painterly language, Buck’s new series blends thick oil paint, sun-bleached fabrics, and intimate fragments of text to explore memory, perception, and the slippery terrain between image and object. Marking a significant shift in his practice, these works embrace form and gesture as vessels for emotion and embodied language.

In conversation with Claire Koron Elat for 032c, the artist reflects on poetry beyond words, slowness as resistance, and why the grid never fully disappears.

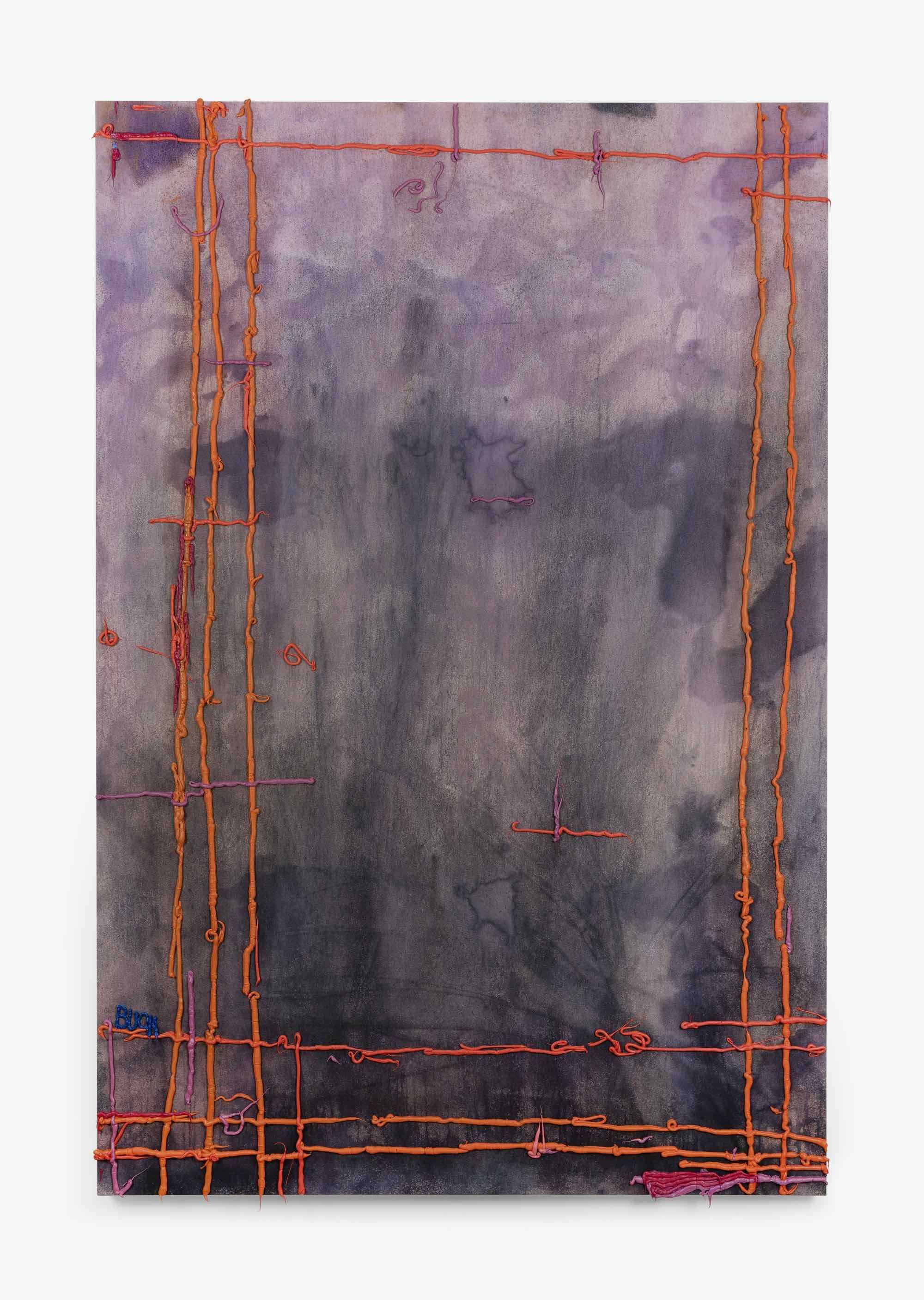

“A man being videotaped fly fishing in Central Park / two men having a conversation about their favorite sport / it rains without my permission,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

Claire Koron Elat: The show is called “Amateur Poems.” How did you choose it and how would you define an amateur?

Dennis Buck: I’m an amateur in writing, and I think an amateur is somebody who does something out of the love for it. They don’t necessarily have to make a living from it. They aren’t dependent on doing it. You can be really good at something and still be an amateur. My paintings also work as poems because they have poems as their titles. That’s where it comes together—the amateur poems.

CKE: The concept of an amateur is interesting in our field because most people made a job out of their hobby. Do you think the idea of an amateur is more related to having hobbies? In your case, you make the poems part of your artistic practice, so it does seem quite professionalized.

DB: I think it’s nice to be an amateur. If something becomes professional—too good or too institutional—it can also be frustrating. I mean, sometimes you’re an amateur and want to become a professional, and then there is this interesting moment of transitioning.

CKE: When you first started your painting practice, did you also feel like an amateur?

DB: Even in this field, I still feel like a bit of an amateur because I have been changing mediums quite a bit. I started with oil painting when I was studying, then I became abstract, and then I started working a lot with silicone. I think you’re an amateur every time you get into a new material. So maybe you’re actually an amateur for every work you make, and then it starts to progress, and it becomes something good that can stand on its own.

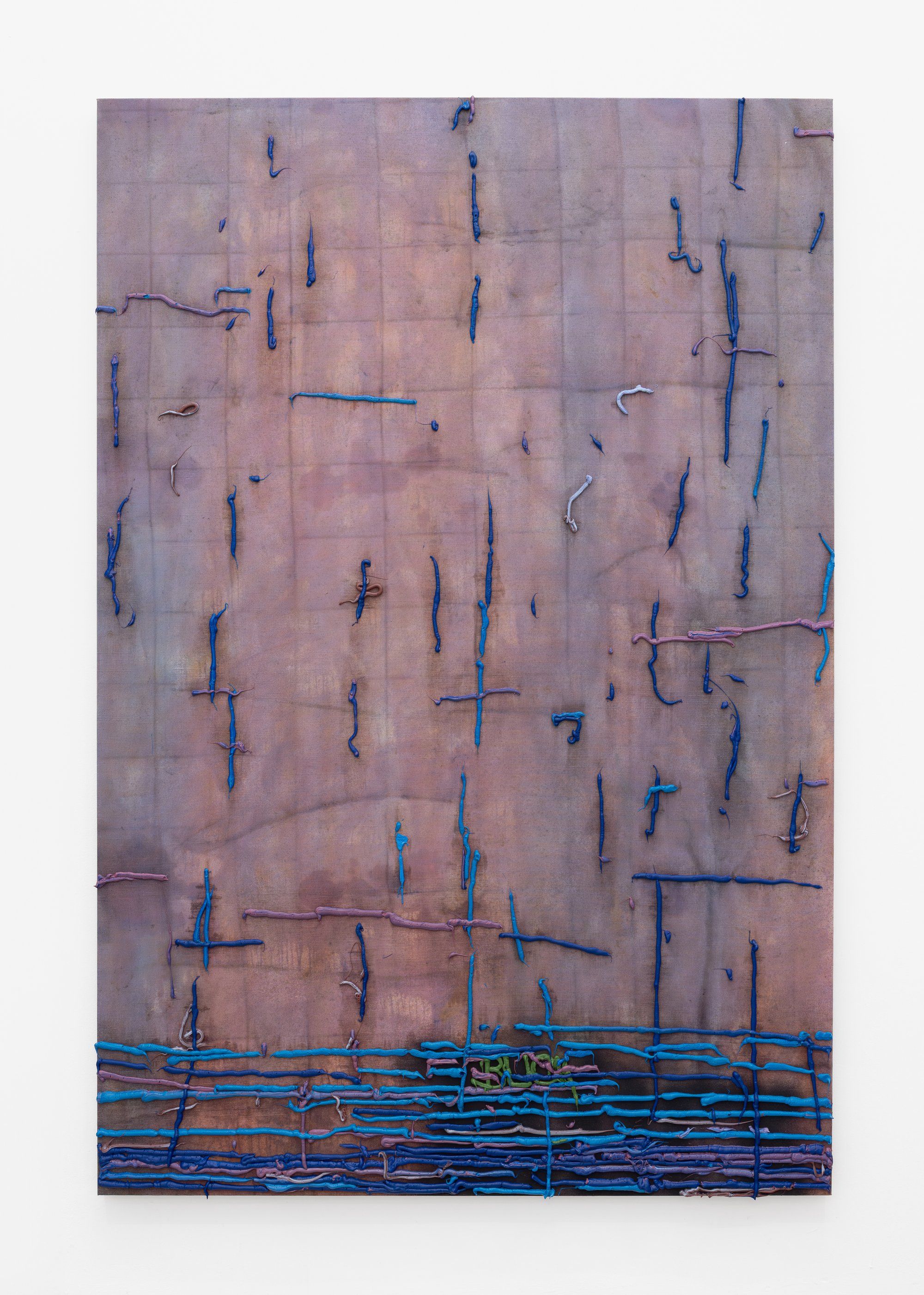

Left: “The liar / is a friend / the liar / does not work / the liar / pays rent / the liar / has dreams / but he lies,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

Right: “My mosquito friend / writes reviews / then she wrote an article / about her writing reviews / and my review is / I want more,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

CKE: Your new works mark a transition from silicone back to oil paint. What prompted this shift? And how does oil paint allow you to mimic or extend the material presence you previously achieved with silicone?

DB: The silicone works are a series, and they’re now in a cycle of new materials and plasticity. I’ve been doing sun-bleached paintings for seven years now, and I started to add oil last summer, because I always wanted to paint on them when they were done with the bleaching process. It didn’t feel right to put silicon on this piece of fabric that basically was made by the sun. It needed a more natural material. And then I went back to oil, which was familiar, as I was using it when I started to paint. But now, I’m using it in a different way. There is a difference, in terms of viscosity for example. I make my own oil paint with somebody that helps me. In that way, we’re way more flexible with the viscosity and how we mix the pigments, the oil, the marble dust, and all these things. There’s a wider range in colors than in the plasticky medium.

CKE: You bleach the canvas in different places, for example at a residency you did on Mallorca but also in your studio in Berlin. Does the place where you bleach them also change something about the final work?

DB: It definitely does, because they’re like a time capsule of the period where they were laying. Sometimes there’s wild animals running over them—or rabbits pooping on them, leaving stains. The poop, for example, throws a shadow on the fabric, and it doesn’t continue to bleach that part. It also changes depending on how sandy or dusty and windy it is—whether it rains or not. A lot of these factors play a role in how the pigments are treated in the work and how it comes out.

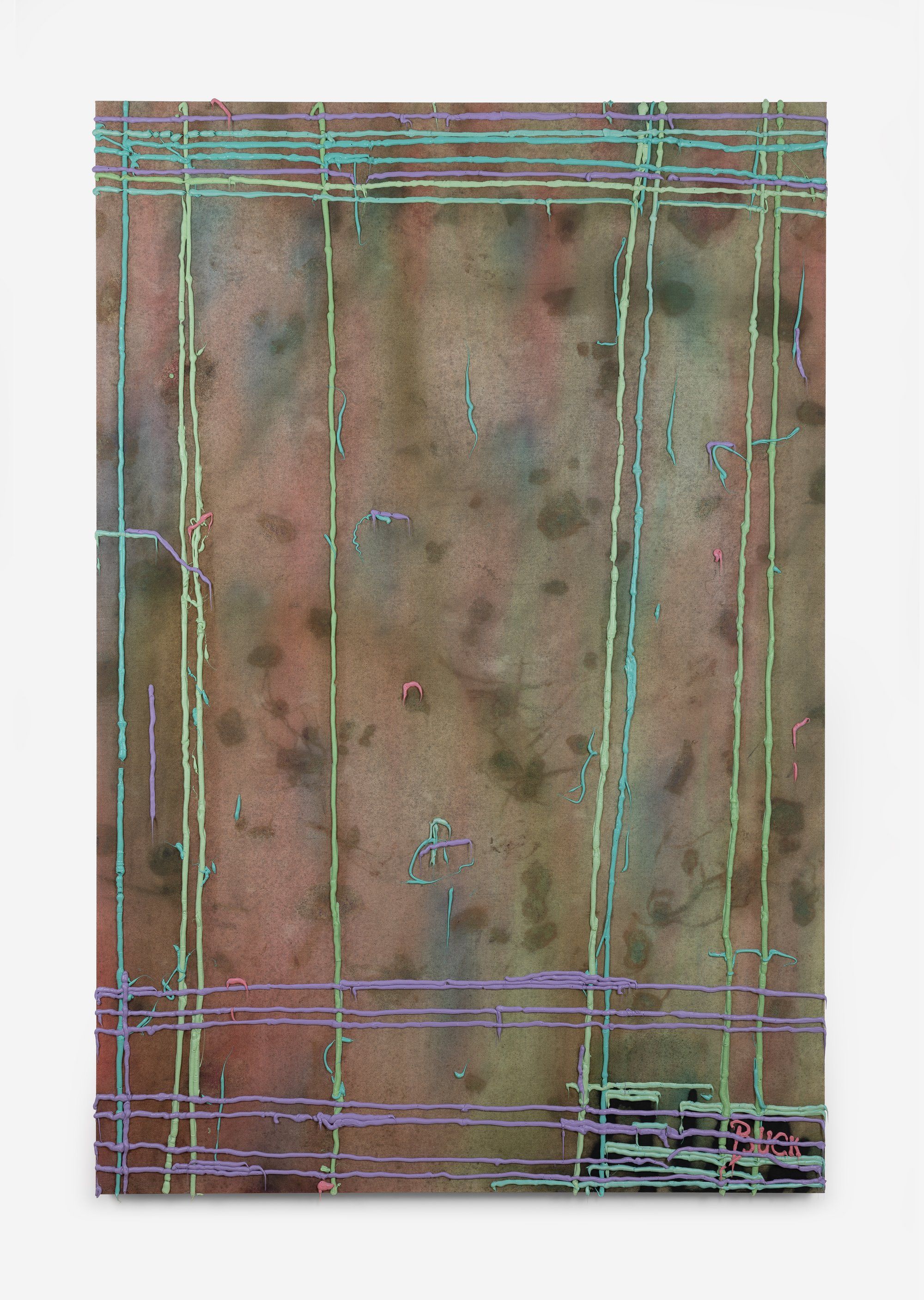

Left: “She used to say / the light is so beautiful / and he laughed / they were young / and I can not / remember him,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

Right: “Shredded Gruyère / pain in my left elbow / the smell of sweat / a beer burp / too much reality / a recipe for a day,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

CKE: The bleaching process seems to be a rather slow, almost meditative, process. Do you like to take time with the productions of your paintings? How long does it actually take for them to be fully bleached?

DB: That varies a bit from how much sun they get, and how good the weather is where they bleach. In the hotter climates, they obviously bleach much, much faster. In Berlin, it sometimes takes up to seven weeks. I think the fastest was at Joshua Tree—it was maybe two and a half weeks. And then with the oil—it happens over the course of maybe a couple of days. It’s quite quick. It’s more of a drying process. That takes a while and takes out the quickness of the painting. The oil has to dry for up to five months until they’re ready to be transported. It’s quite nice for me, because I have to be more structured in terms of when I start and finish something. It’s not like I can produce a show in a week. Also I can’t participate with new works in something that’s more spontaneous, but I also like that.

CKE: Your work is very much interested in the grid, not only as a visual structure but also as a conceptual one. How do you relate to Rosalind Krauss’s interpretation of the grid as both a Modernist ideal and a transcendent form?

DB: I like her viewing or reading of the grid with a rationalist and spiritual meaning at the same time. And I think it gives the painting a formal organization. But for me, it’s important not to be dogmatic. That’s why my grids can also dissolve, and why there’s more chaos and it’s more spontaneous.

CKE: What is your intention with destabilizing the grid?

DB: It just gives me more painterly freedom. But it’s also about the viscosity of the oil paint, and how I apply it. I could 3D print it, but then it would be very straight and the human touch would be non-existent. I like all these errors and failings that make the grid something that isn’t perfect.

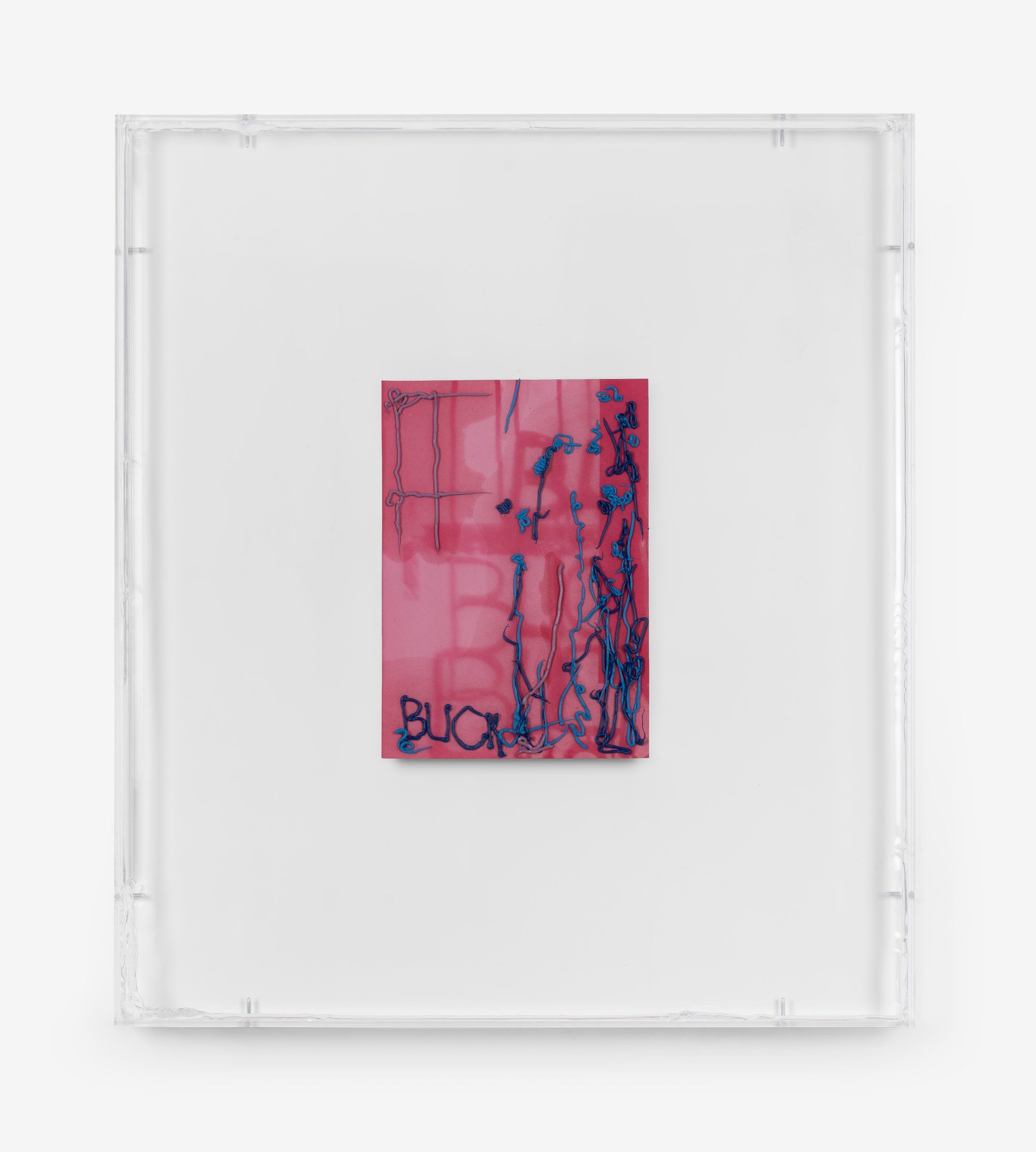

Left: “Baby breeze,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

Right: “My dear friend,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

CKE: In what ways does the historical canon of painting influence your work? Likewise, do current positions in painting have an influence?

DB: New York Minimalism and color field painting played a huge role in my education as a painter. But there are contemporary positions that also work in abstract ways that I’m inspired by.

CKE: How do you approach titling, do the texts precede the paintings, or do they evolve alongside them, and how do you pick the right painting for the right title or vice versa?

DB: The poems usually write themselves. I mostly have a small notebook with me, where I just write half a sentence or two sentences, and then I open it some other day, and then I continue to write. It happens a lot in spaces where I have to wait or when I’m traveling. So, it’s not like I sit down at my studio desk and start writing. I sometimes try, but it goes better when it just happens.

If a painting feels a bit dark to me, and I have a darker poem, then that goes basically hand in hand. And the titles function more like an opening or an addition to the painting, rather than as an explanation or a description of the painting.

Left: “Please keep moving,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

Right: “Hard or soft,” 2025, Courtesy of Ruttkowski;68 and Dennis Buck

CKE: The poems emerge from your personal memory and your daily situations. How do you then translate this into a visual form? In the past, you were working more with text that was also present on canvas, right?

DB: Yeah, the text fell out because it became abstract in a way. And you couldn’t read the whole poems anymore anyway. So, you had the poem paintings before, and now the poems became the titles of the painting—they’re still there and important. But since the writing was not legible, it made sense to do it that way. Instead of having abstract letters, I decided to take out these letters with the exception of my signature. And, instead of a B, I can also just have some abstract symbol sitting on a painting. That was kind of the way it became abstract. It was a naturally evolving thing for me.

Dennis Buck’s new solo exhibition at Ruttkowski;68 opens on July 6 and runs through August 3, 2025.

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat