THE COMING WORLD: Ecology as the New Politics 2030 – 2100

|Aleks Eror

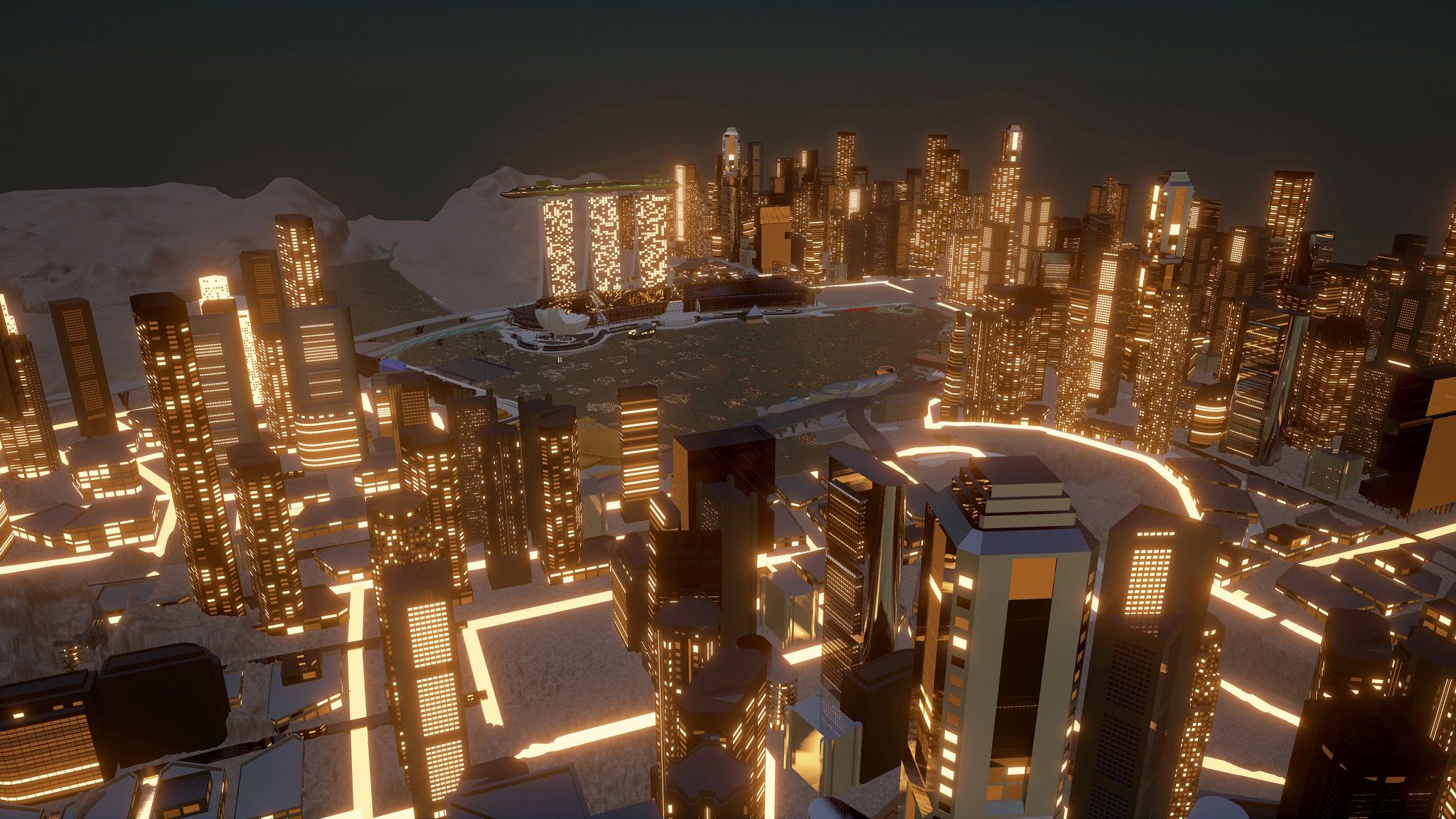

The Coming World: Ecology as the New Politics 2030–2100 is a sprawling exhibition at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow’s premier contemporary art institution, that tackles the subject of climate change, looking speculatively towards a future that’s currently in the making. This fictive future, where global politics is defined by the aftershocks of the impending climate catastrophe, unfolds between two imagined historical bookends: 2030, the year that according to the predictions of biologist Paul R. Ehrlich our planet’s oil reserves will finally be exhausted, and 2100, which science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke prophesied would be the point at which that humans would be able to migrate to other star systems, leaving this decaying Earth behind. However, The Coming World inverts this latter proposition and presents 2100 as the moment that, surely to Elon Musk’s chagrin, we come to the somber realization that there is no planet B and that we must live with the consequences of humanity’s present-day actions.

Using works by more than 50 Russian and international artists, as wide-ranging as Ilya Kabakov and Rimini Protokoll, Garage boldly steps onto a terrain dominated by scientists and politicians, attempting to construct a conceptual framework for the climate struggle. But rather than offering a path to salvation, the show’s curators, Ekaterina Lazareva and Snejana Krasteva, avoid tangible solutions and invite visitors to face up to our collective ecological trauma. It’s a novel approach that raises questions about what role art can play in the climate debate – if any.

What was the inspiration behind The Coming World?

Ekaterina Lazareva: With these political crises today it was very important to find a new sphere where art could be helpful and political and critical, and ecology was one of the most obvious spheres for this. So I think it was very natural because Snejana was interested in ecology and I was interested in activist art – themes that weren’t very familiar to the Russian art scene. It was not easy to find artists who would work with ecological themes in a Russian context. But during the two years that we were planning the exhibition we saw that something actually changed, and now it seems much more relevant than when we started.

Why do you think this was the case initially?

EL: Russian art became very skeptical about activism after the avant-garde experience in the 1920s. It sticks to its autonomous territory and doesn’t try to change the world. Russian art doesn’t really believe in the activist potential of artistic practice.

Snejana Krasteva: Also, the avant-garde legacy is so close to life and so wanting to change life and create a new human, and everything that resulted from that makes this a very bitter experience for many Russian artists. There’s cynicism, but there’s also skepticism. Art can interfere with life so much that it dissolves it, and there’s a lot of critique of the avant-garde that it dissolved so much that it had no power anymore – or that it was not necessary to do that, that art needed to keep its autonomy to remain powerful.

The climate debate is obviously dominated by scientists and politicians. Can art really play a role in this debate?

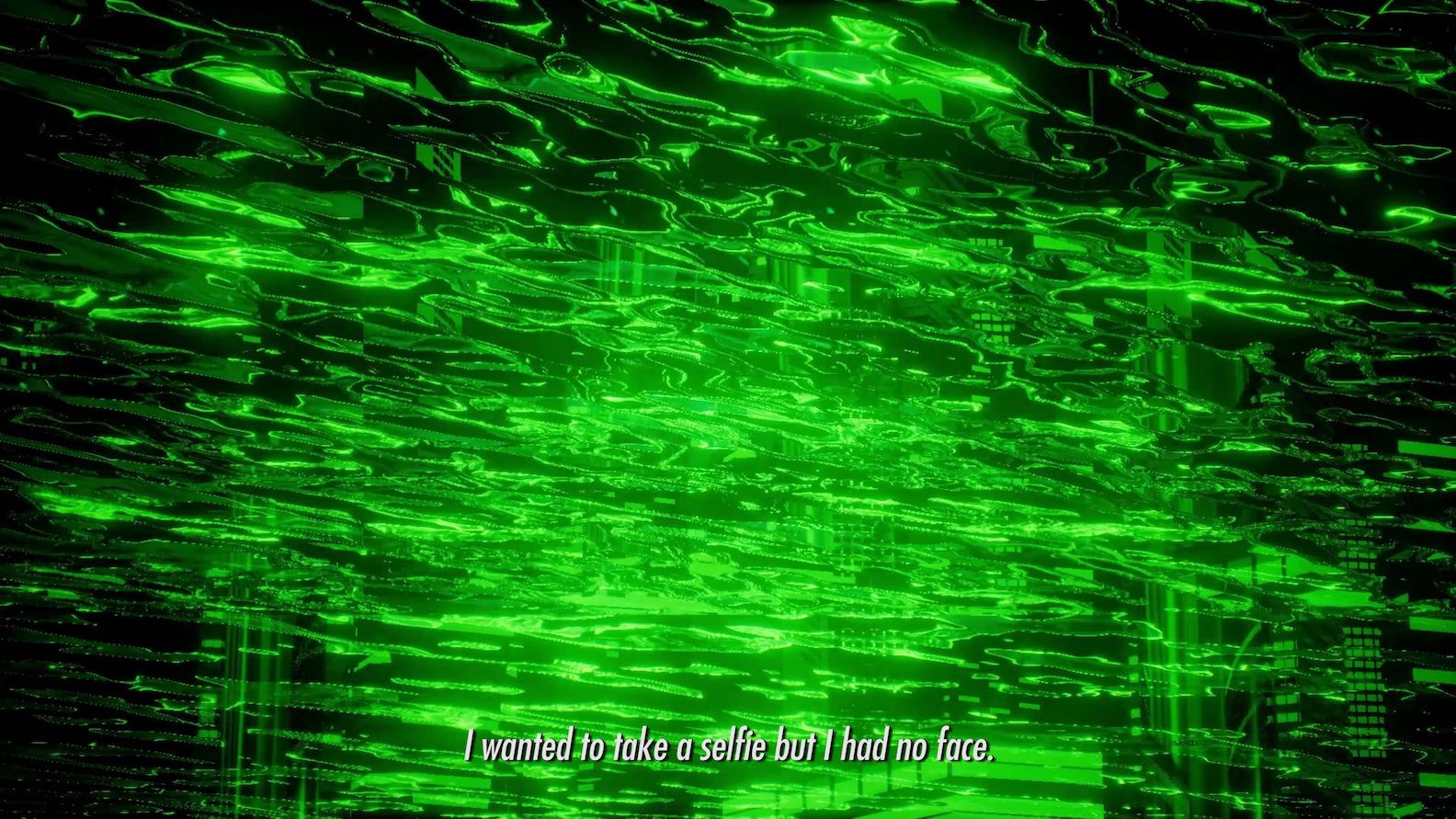

SK: Climate change leads to many things outside of the obvious effects. Rising criminality in regions affected is one. In my mind, the power of art in relation to these reality-related issues, especially the ecological catastrophe that awaits us, is actually not on the straightforward activist level anymore. Its power lies in showing different realities, visualizing what this crisis looks like, what awaits us.

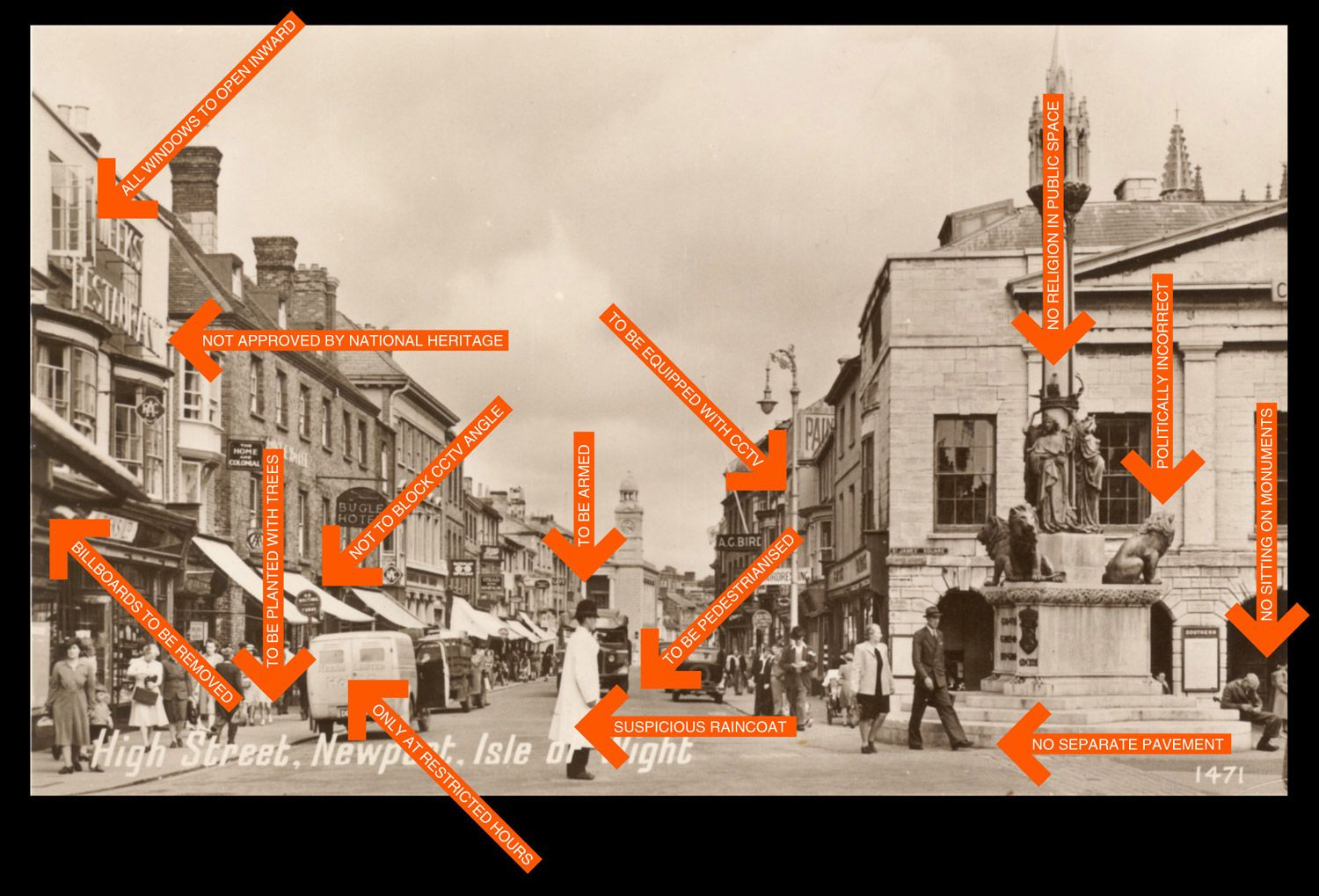

EL: It seems like art is the only territory where all these very different, but very related questions can be discussed together. If you have scientists talking about global warming, they don’t talk about biodiversity at the same time. All these climate debates are very specific and pragmatic. What art can offer is a general overview of all these themes and help us move beyond data and numbers and statistics towards a felt understanding of reality.

When we spoke on the day of the opening, you said that the climate debate in Russia is at a much less advanced stage than in the West. Do you think there’s a greater capacity for art to have an effect there because of that?

EL: The problem is that debate isn’t allowed in Russia, and the public has so few resources to change anything. I would say that people are quite conscious, they just don’t know how they can get together and change things politically.

SK: It feels like in Russia, first of all, you need to start talking about these issues before you say “it’s fucking late” or it’s at the point of no return.

EL: It was very important for a Russian audience to understand that these are not foreign problems that are apart from Russia – because here everybody thinks that we’re a huge country with huge forests, we have a lot of water, we won’t experience a deficit. It’s a very isolationist position, but about two Irelands’ worth of forest burns down every year here. People need to reflect on that somehow.

It’s interesting – historically Russia’s climate has actually protected it from outside threats. When Napoleon and Hitler tried to invade the country, their advance was halted by the Russian winter. Now that’s been turned on its head, and perhaps the climate itself is the threat.

EL: You know there are people who reject climate change and say that Russia will benefit from global warming. For example, melting permafrost will make land available for agriculture. It’s very contradictory.

SK: That’s another problem in Russia: you never really trust official systems and what they tell you.

Do you think that Garage, as an art institution, could break through to people on this topic in a way that the government can’t?

SK: I do think that Garage is a little oasis of freedom. But we work with visual arts here, and artists don’t give very simple solutions to any issues. What they do is look at perspectives that we never thought existed or that raise more questions than answers. That sounds so stupid sometimes when I hear it, but the questions here are not just simple questions.

Are people expecting the exhibition to present solutions to ecological problems? Does that create a certain pressure to deliver upon those expectations?

SK: It does, of course. There was an expectation that this would be more of a pragmatically oriented, of a more activist exhibition. But whenever you put activism inside a museum it always makes it so powerless, in a way. It’s frustrating sometimes to have to say that this is an exhibition, that it works in a different way than a book or a set of instructions on where to recycle.

In the press briefing you said that tangible steps towards sustainability aren’t enough, that there needs to be a conceptual framework for the climate struggle, which is something that this show aims to create.

SK: The show is the conceptual framework. It’s this spaceship that’s sort of leaving, but not leaving the planet – that is held still by what we have not yet resolved and the desire to stay and fix our home.

Do you worry that maybe contemporary art isn’t the most effective medium for this? Not all people who come to the exhibition will have the tools to decipher the intended messages from the works. I certainly feel that’s the case for me – I’m not an art critic, and I think that limits my understanding of the exhibition. Which then raises the question: does art present more limitations than it presents opportunities?

EL: There are definitely limitations of time and place – not everybody will be able to get to the show in these five months. Exhibitions are a very specific medium: the experience is very unprogrammed, and everybody feels something different and thinks something different in response. These limitations can be advantages.

SK: Contemporary art is like contemporary life: it’s fucking difficult and complex. We’re bombarded with information, we don’t know anymore what’s true and what isn’t, we don’t know how to filter information, we constantly live in anxiety that we’re missing out. I don’t think art is easy to understand, and I don’t think it should be. Because our lives are difficult to understand.

“Maybe it’s fine that the ecological crisis is inevitable: maybe it will restore the natural hierarchy that was lost, maybe marginal species will become more central and maybe all the sick, human-made hierarchies will be rethought. Maybe it’s good, maybe the human race deserves to die.”

The exhibition is remarkably free from despair. Did you make a conscious decision to avoid making the show feel hopelessly apocalyptic?

SK: Yes. We had this conversation about individual responsibility and the feeling of guilt driven by eco-fascism – this notion that you, very little you, are responsible for this big ecological disaster, when it’s actually big corporations with big factories that are responsible.

How did you do that?

SK: By having less straightforward work that avoids taking any black-and-white or positive/negative positions. We focused on the ambiguous, the speculative – on work that asked questions.

Recent data indicates that climate change is taking place at a much faster rate than initially predicted, which makes catastrophe feel inevitable. In these circumstances I think that the real value of art lies in its ability to present us with a vision of the future that might help us come to terms with this inevitability, or at least help us mentally prepare for disaster. Do you think that artists should actively avoid solution-based thinking and focus on visualizing the future instead?

SK: One work by Anastasia Potemkina in the show questions if maybe it’s fine that the ecological crisis is inevitable: maybe it will restore the natural hierarchy that was lost, maybe marginal species will become more central and maybe all the sick, human-made hierarchies will be rethought. Maybe it’s good, maybe the human race deserves to die.

Credits

- Text: Aleks Eror