An Anthropologist Discovers Workwear and Gets Over His Dread of Stuff

|Josh Berson

Deferred Maintenance

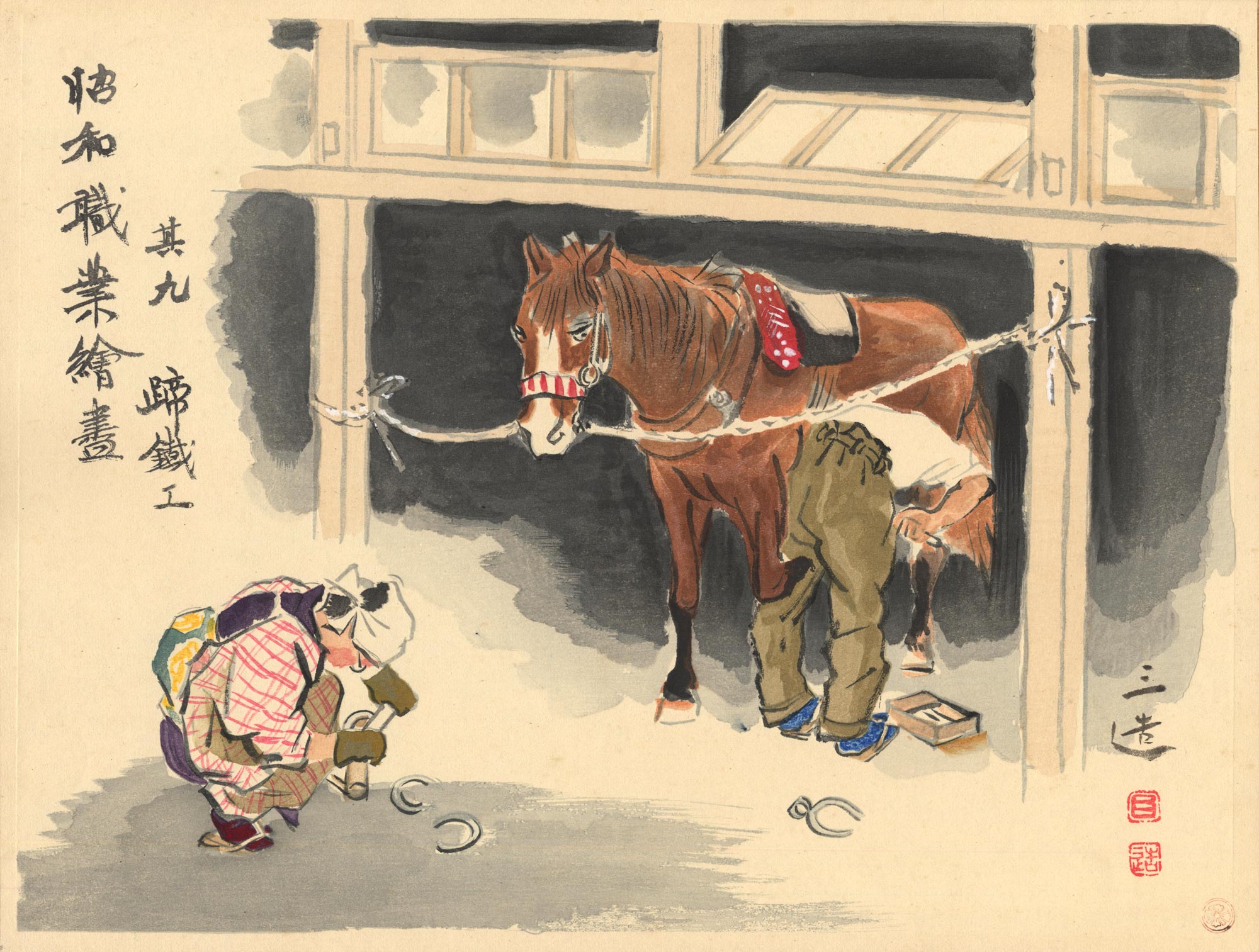

In a woodblock print from the series Sketches of the Occupations of the Shōwa Era (1938–41), the Japanese painter Wada Sanzō (1883–1968) depicts a couple, a woman and a man, making horseshoes. The woman squats before a horse’s stall in a red plaid smock, hair wrapped in a tenugui, preparing the horseshoes. The man stands at the threshold of the stall, fitting horseshoes to a placid sorrel. His upper body is obscured by his posture. His lower body is clothed in a direct ancestor of the trousers I am wearing this morning.

For many people — at least, those with the cultural and relational capital to have spent the past 22 months working from home — the pandemic has been a time of nesting, of substituting material comforts for the consolation of friends. For me, the first 18 months of the pandemic were a time of shedding clothes and resisting the comforts of stuff. This was not something new. Ten years living out of a knapsack had inculcated in me a kind of allergic reaction to the acquisition of new things. A pair of pants might require six months’ brooding, a pair of winter boots two years’. In the years when I sometimes did not know where I’d be living in four months’ time, this habit of deferral had served a kind of protective function, sparing me some of the tedium of moving house. But it had long since passed into the pathological: I had developed a dread of stuff.

When the first wave of border closures caught me between visas and far from the closest thing I had to a home, not to say the person who made it a home, my dread of stuff tipped over into a kind of anti-hoarding syndrome. Shorn of cause to give much thought to how I looked in public, I spent the afternoons tramping around the local football pitch in a kind of demented walking meditation, engaged in the sort of visualization athletes give themselves before a competition — save that in my case the exercise consisted in compulsively packing and repacking a mental knapsack, imagining contingencies, confrontations with harried flight attendants and customs officers. What did I need? What could I do without? How quickly could I be ready to move when the time came?

“Like a state that has spent decades ignoring the upkeep of critical infrastructure, only to find itself unable to procure timber, liquified natural gas, and truck drivers in its hour of need, I was facing a situation of deferred maintenance.”

Even once I was safely back at home, I found myself unable to relinquish my death grip on the fantasy of a life free of stuff, of worldly dross, of anything that might impede my progress when the time came, as inevitably it would, to Go. This worked well enough so long as the weather held and I had no travel plans save periodic runs to the mysterious shop that stocked our preferred brand of rice vinegar. (The one thing I have never been short of is well-made bags for all the stuff I don't have, a distinct advantage in a panic shopping scenario.) But in September, on the first cold morning of the year, I awoke to the realization that in four weeks, after more than a year in which I’d hardly ventured further than a half hour’s walk from home, I’d be leaving for at least six months abroad, much of that time to be spent in the mountains of the American West — and I had no clothes fit for cold weather. Above all I had no pants capable of stopping a cold wind, let alone keeping one’s lower limbs intact slogging up a canyon the morning after a night of snow. Even today, five months of the year the trails of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest demand traction cleats or skis, not to say waterproof shoes, gaiters, and layers. In ten years that may no longer be the case. Dimly, I began to see that my aversion to stuff was symptomatic of a kind of spiritual trauma — and that the cure lay in being outdoors in the cold.

Like a state that has spent decades ignoring the upkeep of critical infrastructure, only to find itself unable to procure timber, liquified natural gas, and truck drivers in its hour of need, I was facing a situation of deferred maintenance. Unlike a state, of course, my personal deferred maintenance situation was easy to fix. The world abounds in guidance in how to get dressed, and as one who had learned to substitute brooding about getting clothes for actually getting them, I had long been an avid consumer. This was not exactly a guilty pleasure: my interest was more clinical than salacious, not to say professional — the greater irony is not that I spent a part of most evenings lurking on /r/Outlier and used the term “upper block” in casual conversation but that I had just spent the better part of three years writing a book on the anthropology of thermoregulation. Now, irony curdled into a sense that maybe I was a fraud, and a double fraud at that: I had failed at renouncing stuff — really renouncing it, renouncing it in spirit — and I had passed up who knows how many opportunities to participate, bodily, in the forms of life I had been writing about.

It did not take much thought to understand what I was after: structure, patina, clothing that looks better the more use it sees. In short order I found myself in possession of the aforementioned trousers, a repro Baker fatigue in an updated silhouette, sewn up in the kind of shuttle-loomed slubby reverse sateen that has made the textile mills of Okayama the object of awed whispers in a certain segment of the menswear demographic. The orSlow Slim Fatigue was everywhere last year. It struck the elusive fine balance between structure and drape, the sober and the playful, that lends an article of clothing versatility. It had character without being demonstrative about it. And unlike the bagged-out polyamide dungarees I’d got in the habit of wearing every day, it would, with time, develop patina — it held open a space for mono no aware, an appreciation of the exquisite impermanence of things. But by the time I chanced upon it, the new season was upon us, and with it the uncertainty of the Drop. Everywhere I turned, resellers were stocking out, like the little squares going dark when everyone leaves at the end of a Zoom. No, the seamstress on the corner insisted, she did not sell tape measures — but wait, she had one on hand, and I could have it for €2.50. I measured myself, bargained with a reseller Stateside about exchange windows, and took a leap.

To my delight the trousers exceeded their billing. For the first time in my adult life I knew the pleasure of a pair of pants that simply fits the moment you put them on. I would not say I wept. But when I tried them on I was swept with a kind of mournful compassion for the self — what had taken me so long? Inspired by my success, I turned to Grailed. This yielded a couple early coups — a beautiful Ues Unevenness Satin Work Shirt in Olive (more a flannel than a satin), new without tags, from a kind soul outside Philadelphia, and an all-but-new And Wander fleece hoodie from a mysterious benefactor in Colorado — and one half-miss, a pair of used orSlow Fatigues from an earlier production run, nominally the same size as my new ones but mysteriously ill-fitting. (It turned out for the best, as my partner then appropriated them.)

“For the first time in my adult life I knew the pleasure of a pair of pants that simply fits the moment you put them on. I would not say I wept. But when I tried them on I was swept with a kind of mournful compassion for the self — what had taken me so long?”

Having come this far, I began to see that perhaps the fault lay not so much with me as with intrinsic properties of the lower body of a biped. Shirts had always presented less of a challenge, and now I turned for insight to the individual who had done more than anyone else to sort out my shirt issues. Courtney Holm is the founder of the Melbourne label A.BCH. I cannot now recall how I came across her work, but she made the first shirt I’ve owned that makes me look like something other than a bedraggled whippet. In fact, she’d been making shirts — and skirts and jackets — for years before she launched a tailored trouser. Trousers, she told me, are uniquely hard to get right. They take a lot more wear than other categories of clothing: tensile wear through all the squatting, bending, sitting, and walking we do, not to say abrasive wear — we’re far more likely to support ourselves with a prop under the pelvis or legs than the trunk. Tailored trousers need to accommodate the vagaries of digestion and menstruation. And if, like Courtney, you’re committed to full biodegradability, elastane is out — despite claims from some of A.BCH’s peer labels, no one has come up with an elastomer that resists microfiber shedding and biodegrades in the wild, i.e., without the addition of special inoculants. Today, when most of us are measuring ourselves at home and buying our clothes online, a small label like A.BCH is at the mercy of customers’ often misguided understanding of how to measure themselves — say, adding a couple cm to the waist to account for off days (a properly tailored trouser will be cut with seam allowances to accommodate day-to-day variation in the size and shape of the body). If you’re running your own cut-make-trim, Courtney told me, incorporating made-to-measure customization into an off-the-rack manufacturing process is not all that difficult. The difficulty is getting the measurements right in the first place.

Since the start of the pandemic, many people seem to have given up on fitted trousers altogether. But there will, I trust, always be those who aspire in an abstract way to the corporeality, if not the cold, the pain, the exhaustion, the tedium, of agricultural and industrial work. It is unlikely my own fatigues will ever be called upon to clasp the lower foreleg of a horse, like those of the farrier in the Wada sketch, though when they have acquired enough patina that no task is considered beyond their remit, they may, in time, see service splitting wood, lighting a fire, digging a posthole, cutting up a fallen tree with a hacksaw. We are losing, the artist and philosopher Simon Penny writes, our awareness of how much skill is folded into industrial manufacturing activities. Our screen-mediated lives have given rise to a wide-ranging sensorimotor debility. Penny quotes Roger Kneebone, professor of surgery at Imperial College London, lamenting, in 2018, medical students’ declining “ability to do things with [their] hands, with tools, cutting things out and putting things together.” In this light, workwear fashion begins to resemble something like phantom limb syndrome, an irremediable longing for a sheared-off form of bodily engagement with the world of things.

But perhaps it is — or could be — something more: a gateway back into the world of things, of things loved for the skill they exhibit in the making, for the wear they show in use. Among my other discoveries, in this season of deferred maintenance, has been Herrie, the eponymous label of a Savile Row-trained tailor who, in 2020, lost her shop in Nashville to a tornado. Herrie and her partner Kyle decamped for Vermont, where she has started making jackets in ready-to-wear sizes. Herrie’s jackets are slugged chore jackets, and they do draw inspiration from French chore coats of the mid twentieth century, not to say US and British military field jackets of the same era and cool-weather noragi of the sort that make frequent appearances in Wada’s Sketches of the Occupations of the Shōwa Era. You could, in fact, imagine wearing one for outdoor chores. Admittedly, when you buy something from Herrie you’re committing to her distinctive vision of post-historical workwear — not quite cosplay, but something you might call loompunk. But what is most captivating about Herrie’s project is how the clothing she makes fits into a broader vision, of a way of life. This winter, Herrie and Kyle are building a new workshop — with their hands, in the snow. Here is Herrie in knit sweater, snow pants, and work gloves, felling spruce with a chainsaw, raising a gin pole to build an outdoor staging shelter. It is enough to make you want to be cold.

Credits

- Text: Josh Berson

Related Content

THE COMING WORLD: Ecology as the New Politics 2030 – 2100

Paranoid, and Cousins: CHRIS DERCON in Conversation with BROOMBERG & CHANARIN

Between China and the Arabian peninsula, a “maritime silk road” powers global capitalism – even in the age of the cloud. LALEH KHALILI explains.

Revenge of the Real: BENJAMIN BRATTON on the West’s Covid Ineptitude

“Solidarity is the Only Remedy for Embitterment”: Interview With HEINZ BUDE

Meth Modernity

ZYGMUNT BAUMAN: LOVE. FEAR. And the NETWORK.

IYKYK: An Interview with Chris Kraus and Hedi El Kholti, Editors of SEMIOTEXT(E)