Paranoid, and Cousins: CHRIS DERCON in Conversation with BROOMBERG & CHANARIN

|Chris Dercon

Artist duo ADAM BROOMBERG and OLIVER CHANARIN are propelled by a suspicion of images. Stemming from an editorial post at Colors magazine, their partnership as photographers has gradually morphed into a form of rhizomatic anti-journalism.

They are hackers who operate in live terrain – embedding themselves as conflict reporters in Afghanistan, or masquerading as anthropologists amongst Pygmies in Gabon. Their projects spill across vectors of history and geography, sprawling ad infinitum through the paranoiac logic of and, and, and, and … They are surrealists with plane tickets and IP addresses. Tate Modern director CHRIS DERCON visited Chanarin and Broomberg in their studio on Princelet Street in London, where he was greeted by a dog named Otto Dix. It was only the first layer to a conversation that oscillated fluidly from Instagram to Isis, from Yiddish Theatre to South African octogenarians.

CHRIS DERCON: Let’s start with your dog. Why is he named Otto Dix?

OLIVER CHANARIN: When we were in Cairo doing a residency at the Townhouse Gallery, we did a project about unearthing the Egyptian Surrealists. The founder of the movement, Georges Henein, was an Egyptian who studied in Paris with Breton. When he went back to Cairo, he wrote the manifesto of the Egyptian Surrealists, which was called Long Live Degenerate Art. We did a lot of research into that movement, and at one point, we wanted to invite scholars to create a séance in Cairo to go back and connect with all the Egyptian Surrealists, and also the members of the 1937 Degenerate Art Exhibition – Otto Dix being one of the them.

How did you stumble across Egyptian Surrealism? A lot of scholars have become interested in it. Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, who curated “Tea with Nefertiti,” are now working on an ambitious show about Surrealism in Egypt.

ADAM BROOMBERG: We arrived to do our residency and there was a show scheduled to open at the Townhouse that day. But the government came and censored it. So we were asked by the director William Wells to concoct a new show. That night we met Maria Golia, who had just written a book called Photography and Egypt. And, in that book, there is one paragraph about the Egyptian Surrealists. And we thought, “Hang on a second, this can’t be true!”

OC: But there wasn’t much information about them. There were only a few of them.

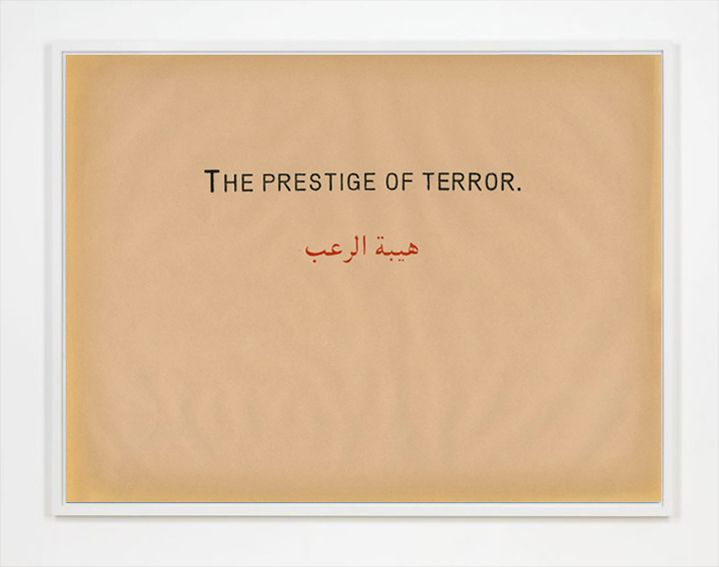

AB: So we proposed to do a show in reverse. We got the local sign painter to paint a sign saying, “Anyone with any information about the Egyptian Surrealist movement please come and bring it.” This old Trotskyite came in, who lived in a tiny apartment filled with amazing books – Russian first editions. He smoked cigarettes, ate peanuts, and drank beer – that’s what he survived on. And he was the only person to translate Georges Henein from the French into Arabic. He translated probably one of Georges Henein’s most heroic and brilliant pieces, The Prestige of Terror – which he wrote just days after Hiroshima was bombed – in which he accuses the allies not of defeating fascism, but of assimilating their abuse of power.

OC: The thing about the Egyptian surrealists was that they were very aware that it was a bad time to be a Surrealist in Egypt. It was a moment when there was a huge rise in Arab nationalism, so this Francophile movement was totally defunct and people didn’t really want them. They were very aware of their own demise and they spoke obsessively about their own death.

“If you type “Egyptian Surrealism” into Google, our names come up first. That’s the tragedy of the Internet.”

AB: If you type “Egyptian Surrealism” into Google, our names come up first. That’s the tragedy of the Internet.

In a way I think your method of working is very much influenced by the “paranoiac critical method” of utilizing spontaneous and unconscious links, which is very crucial for the Surrealists. Rem Koolhaas, the famous Dutch architect, brought it back into actuality, because Rem is also someone who is trying to look beyond and behind something. Then, just like in serendipity, you always find what you were not looking for. Everything is connected with everything else. Are you guys like a new type of Surrealist?

AB: We’re paranoid and we’re cousins. So everything is connected, yes. We discovered after working together for twelve years that we’re related.

OC: I don’t think we’re Surrealists. Counter-insurgents, maybe? We insert ourselves into systems of power, like athlete’s foot.

You’re hacking.

OC: We often find ourselves in these strange relationships with power.

AB: Afghanistan is a good example.

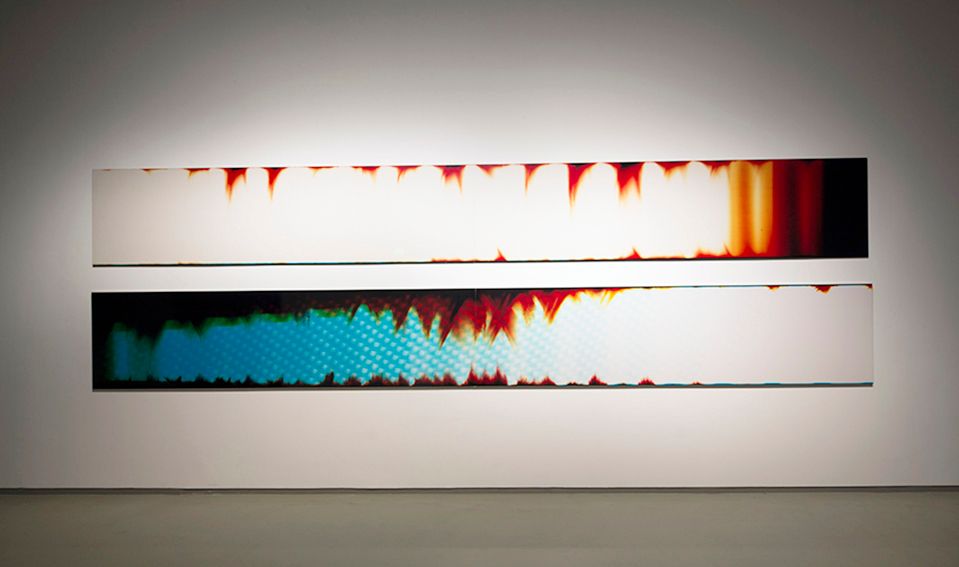

OC: Yes, when we were working on The Day Nobody Died, we were embedded within the British army as journalists.

AB: We lied and said we were journalists.

OC: If we said we were artists, we never would have gotten in there. We were making this work, and after about twelve days in Helmand Province, the military turned around and said, “These guys are not doing what we need them to do.”

AB: In fact, we were just making photograms, not photographs.

OC: We’re now engaged in a new project related to cadet performers, which is similar in a way. We’re spending a week in a cadet camp on a military base in Liverpool. They’ve given us access, but we’re bringing a clown. They don’t know about that. This clown is actually a bouffon, or dark clown. The bouffon’s job is to mock power.

AB: In Medieval times, the king would allow the bouffon to come in from the margins of the city, and, for that day alone, he was allowed to undermine power. Although if he pushed it too far, he was decapitated!

OC: Risky occupation.

What will your bouffon be doing?

AB: We’ve conscripted a very strict bouffon, who’s coming with us to teach the kids how to unlearn what they’ve spent the day learning – military timing, marching, discipline. One of the disciplines that a bouffon learns is how to move around the room as a group without anyone taking the lead, which is the opposite of a military parade.

OC: In our minds, we keep bouncing between the idea of precision and chaos. The clown obviously represents chaos in relation to strict military discipline. We’ve also made a photograph of a strange and rather magical object. It’s the result of an improbable moment when two bullets have accidentally hit each other during battle and fused. We found a man in a small town in Washington who is a collector of these fused bullets. He’s got ten of them, which is the biggest collection in the world! There’s a precision and chaos built into these molten lumps of lead, but when they are photographed with a macro lens and printed the size of a wall, they resemble some kind of meteorite.

The famous photo-historian, Val Williams, once quoted your statement, “Everything that happened, happened here first in rehearsal.” In a way what you do is go to moments before the so-called “documentary photography.”

OC: It’s the opposite of aftermath.

You’re trying to fabricate something that leads up to an accident, to slow it down.

AB: I’d like to respond by bringing in the word “fiction.” On a number of levels, fiction cannot help but be documentary.

You also have a fascination with the machine – with the technology of the photography.

OC: We’re interested in the politics of the material. We’re opening a show in two days about the history of Kodak and its relationship to race. For another project we did in South Africa, we looked at how Polaroid supplied the Apartheid regime with machines to do all the passbook pictures. They developed a camera that had this button on the back to increase the flash when you’re photographing somebody black. It’s a piece of equipment that embodies a particular ideology. And I think that’s what we’re interested in – that intersection of politics and technology.

AB: But we’re also interested in narrative. When Samora Machel took over in the 70s, he invited Jean Rouch and Jean Luc Godard, because there was no television station. He said, “Listen, let’s not follow the Western model. Let’s revolutionize this thing.” And Godard famously said, “I’m not using Kodak, because Kodak is predicated to white skin. It’s racist.” And so he used video.

You made a work about that, no?

AB: We were invited to enact one of these ridiculous 19th century commissions, “Come and document Gabon!” Two white boys for two weeks. And we went on a five-day journey to the end of the primary rainforest to witness a very rare Pygmy ritual. We made sure we took only the film that Godard would call racist – unexposed film that predated 1970. We shot forty rolls, came back, and it took six months to process. And when it was finished, they told us, “Bad news. One picture came out – and it’s pink.” That was beautiful for us.

Tell me about your work with prisms and optical technology.

OC: Those are for our upcoming show in Warsaw. The optical industry was important during World War II, as it produced all of the optical equipment for German weaponry, and for that reason became a target of allied bombing. That’s partly why Dresden was flattened. But then, at the end of the war, the Russians came and the first thing they did was go to the Leica factory. They stole all of those technical drawings and spawned an entire optical industry in Russia.

AB: We’ve been collecting those original prisms, which – along with the bullets – are essential to that idea about precision versus accident.

OC: We’re calling the film about army cadets The Double Act. In slapstick comedy the “the double act” relies on those types of oppositions – a fat man and a thin man, Laurel and Hardy, a clever guy and a stupid guy. We’ve been doing a lot of research into the history of slapstick comedy and the way in which pain is performed. When you see someone slip on a banana skin, and they fall over and hurt themselves, it’s funny because the action takes place within a comic frame. That allows us to feel less empathy for the person. We’re very interested in that, how the spectacle of someone else’s pain is funny.

How would you relate that to how we react to the videos of ISIS?

AB: There’s no comic frame there.

OC: Yet the only time you see pain performed to that extreme on film or TV is in slapstick. You’ll see an entire house fall on someone’s head, and then they get up and they’re okay. Or an anvil falls on a mouse, and he gets squashed, but he just pops back up. That’s the only time you see such extreme pain. A beheading is unthinkable outside of this comic realm. In our little film, we want to create that sort of tension. So you’ll see cadets marching around and parading, but then you’ll see these moments where they’ll be learning to fall over and play dead, or learning to slap each other and make it look realistic. These things will be cut in a way that you won’t be able to tell if something is official, or if it’s the influence of the bouffon.

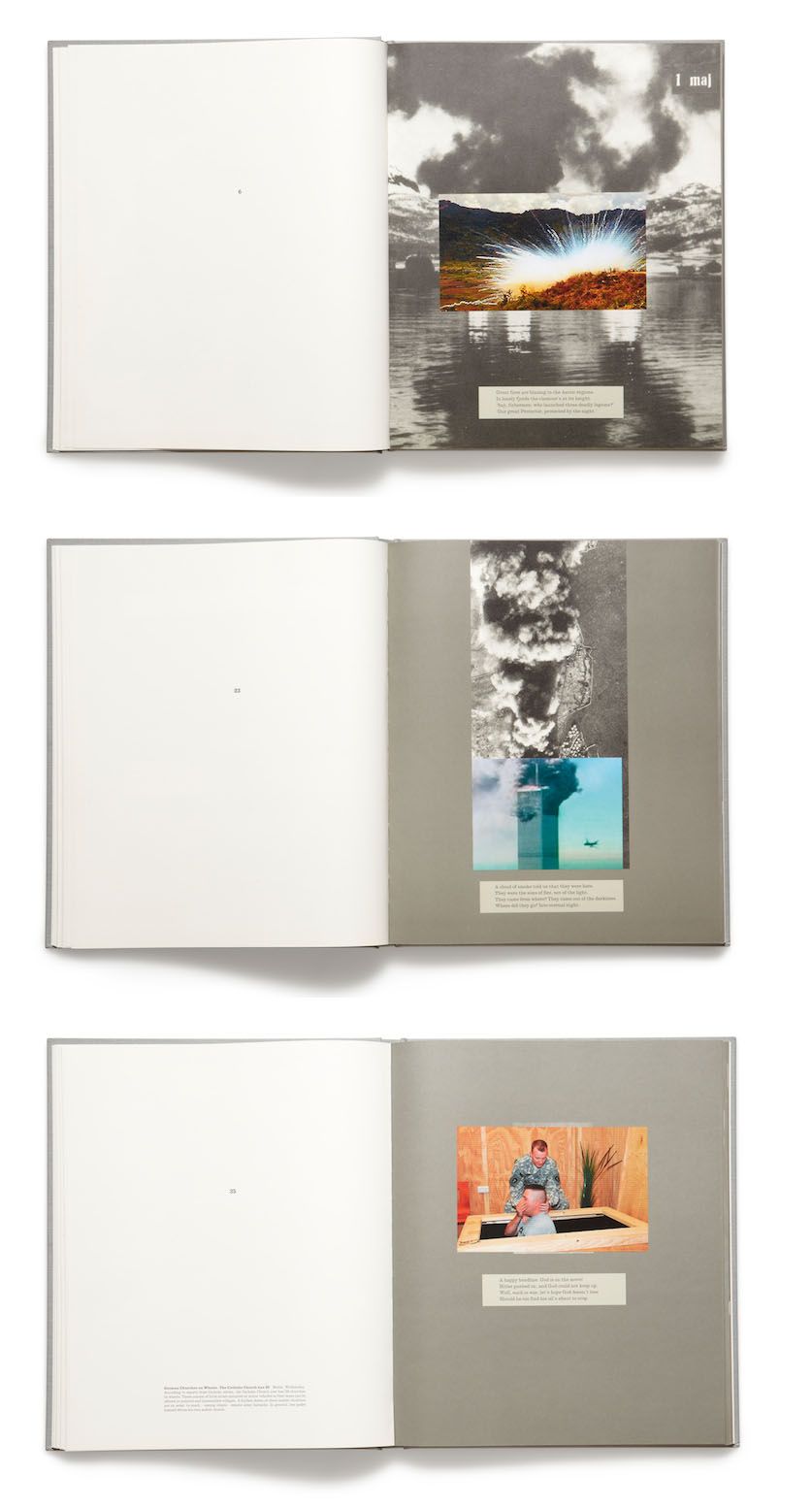

AB: We once produced a book called the War Primer 2, which hijacked a book by Bertolt Brecht. And we put the pictures on top of his pictures, and on the last page, instead of a photograph, we put a weird rectangle, which was there to represent a picture that we know exists, but has never been seen – a photograph of the body of Osama bin Laden, after he was captured and assassinated. It exists as a verbal description in an interview with one of the American soldiers who was there, but perhaps we will never see it.

OC: The soldier describes this ridiculous situation – quite comical actually – because they wanted to identify Osama’s body, and to do that they needed to measure the length of his body, but nobody had a tape measure on hand. So one of the soldiers lay down next to the body, and they took a picture to prove his height. He was famously tall. They used the soldier as a human tape measure. And that picture hasn’t been seen because the Obama administration has very cleverly withheld it.

It’s becoming almost impossible to see things as they are. What is a true image? It seems to be that the way we are seeing something is the way you make us see something. Maybe that’s the way of the future.

OC: I think that has to do with technology as well. The picture is there to act as a piece of evidence. Yet, we still need those pictures. They still need to be made, and we need things to be recorded as evidence of atrocities. But it’s totally un-professionalized. Whoever’s there will do it.

But we don’t want to believe the ISIS images. We don’t even want to look at them. We get rid of them.

AB: Because they’re not on “our side.” But this is a fake definition, because it’s almost an autoimmune problem now. Some of these ISIS people are coming from Hackney. You can’t carpet bomb Hackney. What’s happening now is that the people in control of the jihadi media are coming from inside our system, but they’re out of official control. So it’s a body that’s turning in on itself.

It’s like a cancer of images.

AB: There was a time when there was “good” and “bad,” and we sent out our photographers and they photographed the “bad.” But now the “bad” is being photographed by the “bad people,” who come from our own communities. So it’s a fucking quagmire.

It’s a very important issue. Who is in control right now? And then you also look at Instagram, where we have invented an entire genre that never existed before. If you look at something like the selfie revolution, it’s something that has gotten equally out of hand.

OC: Do you have an Instagram account?

No. But fashion models only get work when they can prove they have so many followers.

AB: Curators, too, let me tell you.

The selfie thing is becoming slapstick as well. Why do we – as adults – constantly place ourselves as a comedic act on the world stage?

OC: It’s economics. It’s a lot cheaper to have consumers produce their own content than to produce the content for them.

“Perhaps photography has reached the point of the grotesque. ISIS is the grotesque, but Instagram and selfies are also the grotesque.”

Perhaps photography has reached the point of the grotesque. ISIS is the grotesque, but Instagram and selfies are also the grotesque, which means that we finally have come to realize that we cannot achieve this ideal life.

AB: And what’s the reply of the art world? To go back to 1960s, Cal Arts abstraction. Because that abstraction is the place of the hallowed, non-vulgar, beautiful, and intelligent. I just find it reactionary.

You’re not the only ones who find the newest abstract painting reactionary.

AB: It’s a blank thing on a blank thing on a blank thing, and that’s supposed to be our “sophisticated response” to this vulgarity.

Have you ever been asked to make a fashion campaign?

AB: We actually did one in Cairo. For POP Magazine. Men dressed in the most beautiful women’s clothes.

OC: And we once photographed Naomi Campbell with her Rabbi! She refused to do the shoot without consulting him every ten minutes.

AB: So we put him in the shoot–a little Jewish man with a baseball cap.

So, if a corporation like Prada offered you a campaign, what would you say?

OC: Well, we disagree on this.

AB: We would not do it.

OC: I would consider it. It depends on what it was.

As long as you have your freedom?

OC: I would be interested in the tension of trying to make something that was pushing back against the machine.

AB: I would not.

OC: Luckily, we’re two different people. If we were the same, it would be so boring. Because there’s two of us, we can’t just pick up a camera and take a picture. We always have to have a conversation about it first.

For me, that’s a critique I have of your work. In some projects, I have the impression there is too much commentary – too much, “and, and, and, and …” Why are you so interested in adding layer after layer after layer?

AB: We have a real suspicion of images. They need words to somehow contextualize them, but there’s also something insufferably curious about them. We went to Mexico to dig up the wreckage of an airplane. We were sitting at a bar, drinking Mezcal with a curator, and Ollie remembered that in one of our first books, Fig, we photographed the skeleton of a dodo. Now, I don’t know if you know this, but there’s no complete skeleton of a dodo. Every skeleton is made up of many pieces. And we decided that “Dodo” was a perfect name for this thing, because we didn’t find the airplane. We found many pieces. Then we discovered that there is only one dodo egg left in the world, and it’s in East London, South Africa – where we both come from. So, of course, we have to photograph the dodo egg. And then there’s another layer.

OC: Yes, the next layer is how do you photograph an egg. What’s the right approach? Simon Baker once told me that photographing an egg was the first task of any photographer enrolled in the Bauhaus. It was only after you mastered photographing an egg that you could go on and try other things. So there were a series of games and experiments and instructions on how to photograph eggs, which we used.

But there must be a moment when you say, “Stop! We are not going to add that layer!”

OC: I think we’re both kind of just tickled by these things. It’s not even intellectual.

AB: We’re not that disciplined. And we’re not professional. I think most artists have immediately recognizable aesthetic strategies. Their own charming approach is immediately there. And then you go into these collectors’ houses, and they’ve got one of everything. They want to be able to take their friends and say, “This is a this. And this is a that.” But you can’t do that with us, because it’s, “and, and, and, and …”

But are you not afraid that, at the very end of the chain, the beginning is somehow lost?

OC: We have an internal conflict about it. On one hand, we want to make a soup that doesn’t make a lot of sense – that kind of takes you on a journey where you do lose the early thread. But then there’s another impulse to explain the “and, and, and, and …” To be more didactic.

AB: There’s also no end. Because you take a walk, and you stay on that walk. Herzog knows what that walk is, because he walked from Munich to Paris. There’s also a great story about David Goldblatt walking from Canada to New York.

OC: He cycled.

AB: Oops. Yes, he cycled to meet John Szarkowski at the MoMA.

OC: The photography curator.

AB: And Szarkowski said, “Your work is shit, but I’ll buy two because you fucking cycled here.”

This method of “and, and, and, and …” also connects you with a tradition that feels incredibly non-Anglo Saxon.

OC: Well, we are not Anglo Saxon.

Has it anything to do with Jewish culture? This whole idea of “the double act”?

OC: Yes, being Jewish is important. Right now we are researching the history of Yiddish theatre. It’s an incredible untold story, and we are hoping to make a series of feature films: imagine The Godfather for Jews. You know, when the first Yiddish theatre in Britain burnt down, the principle actor – a guy called Joseph Adler – went to New York and basically invented method acting. His daughter, Stella Adler, then trained Marlon Brando. At the same time, the directors of that theatre went to LA and started Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. They spawned the Hollywood industry. So we’ve been tracing back where these guys came from, and they all came from Odessa. And the reason that they came here was that the Czar – Alexander II – was assassinated and theatre was banned. So this form that was invented in the late 19th century, and existed for 50 years, was then destroyed.

AB: Then we discovered that when the assassins of the Czar were being marched to the gallows, they were surrounded by drummers. Why? To muffle their voices if they tried to shout out their ideology to the crowd. The drummers would get louder, effectively censoring them. Which led us to the idea of drumming as a political weapon. Which brings us back to “the double act”.

OC: Years ago, Adam and I did a project in South Africa where we went to my grandmother’s old age home. It was a Jewish old age home in Johannesburg. She is dead now, but she was in her late 90s. We interviewed all these little old ladies and we had the best two weeks of our lives. They described their experience to us as young girls escaping from pogroms in Lithuania, Poland, and Russia, getting on boats, arriving in Durban, and seeing black people. What’s so interesting is that the Jews had escaped this horrific situation where they were at the bottom of the social pond, but they arrive in South Africa and they were instantly elevated above the Blacks.

AB: And I think that kind of immigrant mentality – with all its baggage – is engrained in both of us.

Credits

- Interview: Chris Dercon