A Serious Journalist Can't Accept Gifts

The fashion critic exists in a space of ambivalence. Both insider and observer, they are part journalist, part socialite, part sharp cultural commentator. Their words used to launch designers into the stratosphere or cement their downfall. And for much of its history, fashion criticism remained an exclusive club, guarded by pedigree.

With the blogosphere and influencers, these barred doors were battered down and now content creators even have their profiles featured on The Business of Fashion.

The French fashion commentator and content creator Lyas is a shining star amongst them, and his BoF profile suggests that he is “formidable voice in fashion critique,” who is “making waves in the industry with his incisive runway narrations and analyses.”

Born Elias Medini, Lyas has gained hundreds of thousands of followers on Instagram and TikTok with his profound knowledge of the archives and his charm and no-holds-barred approach to storytelling have earned him sympathy from Galliano and backstage invitations to Rick Owens, among others. In 2024, he was named fashion correspondent for Interview and he has recently ventured into the digital couture space with the fashion gaming app Fenzy.

The interview with Lyas is accompanied by a visual story curated by him—his playful twist on legendary fashion critic Suzy Menkes’ dictum: “If you’re a serious journalist, you can’t accept gifts.”

MAX ROSSI: You call yourself a “fashion commentator” rather than a critic. What’s the difference, and what exactly do you do?

LYAS: I didn’t study journalism, so I’m pretty cautious. I know there’s some animosity between journalists and those who pretend to be journalists, and I love my journalist peers. I respect them. I don’t want to have a title that I didn’t graduate to get. I think commentating gives me the freedom to build and narrate things. It’s about storytelling, and I find critique a bit restrictive as well. I just say that I talk about fashion, and I think there’s nothing more to it.

MR: Most of your work gets shown on TikTok and Instagram. Why these platforms?

LY: Because they were the most accessible. It was—and still is—so democratic. Everyone can use it, and I think it’s a wonderful tool that you can use to your advantage and actually do good on—or not. But I think my original intention was simply to publish my thoughts and find a community that could resonate. And somehow, they did.

MR: You come from film and drama studies. How does that shape the way you see and talk about fashion??

LY: I think it allows me to look at fashion in a more narrative way—as a means of storytelling, which, for me, is the only way I’ve ever been able to make sense of fashion. Growing up, I understood it by crafting stories around the characters wearing it, imagining who they were based on what they wore. Even now, the collections and brands that resonate most with me are the ones that build a narrative and have something real to say.

But I think, in general, everything has influenced my sensibility and visual taste—cinema, books, museums, and the art I was exposed to when I was young and living in Normandy. Moving to Paris completely blew my mind because of all the culture, and I started drawing inspiration from so many other artistic fields. I think that’s the most important thing: you have to be curious about everything. I just got this book, Rimbaud in New York (1978-1979) by David Wojnarowicz, which is this amazing series of photographs of a guy wearing a cutout mask of Rimbaud—the French closeted gay poet—wandering through the streets of Manhattan. It’s also a take on queerness. If you look at the latest Rolling Stone cover, where Timothée Chalamet wears a printed cutout mask of himself, you’ll notice it’s a direct reference to Wojnarowicz’s work. And that’s what’s so cool—when you take inspiration from things outside of fashion, that’s when your mind expands, and you actually get better at understanding fashion.

MR: Yet, 60 seconds isn’t a lot of time. Does the format push you to be sharper, or do you feel like you're cutting yourself off at times?

LY: I don’t think I limit myself. I love restriction—I think it breeds creativity. When you’re put in a box, you find ways to explore every constraint of that box. I like that you have to catch the audience in the first two or three seconds—that’s my challenge. When I’m given too much space and freedom, my mind starts to wander. If I wanted to do long-form content, I’d be on YouTube, or podcasts, or I’d write. But I also like that TikTok is visual, and that it feels democratic. People don’t have an attention span anymore, so you have to find new ways to talk to them. You have to be with your times.

But now it’s getting longer. Before, all my videos were super quick to be catchy, keeping them under a minute. Now, I also do two or three minutes. We’re slowly but surely going back to long-form content. You can even post up to ten minutes on TikTok now.

MR: Posting your reviews on TikTok and Instagram gives you total freedom—no editors, no press guidelines. But where do you draw a line? What won’t you say?

LY: I will never talk bad about emerging brands, smaller brands, or young designers. Even if I think a collection is truly awful, I won’t say it, because there’s no point in tearing down people who are trying. If I have to go in on a brand, it’s going to be the big ones who can take it. I think you have to have morals.

MR: At the same time, there’s no filter or fact-checking. Hot takes spread fast. Do you think there’s a danger in that?

LY: I think in a year where Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk dismantle fact-checking and let anyone say basically anything, we have to be even more careful about fake news and misinformation. It spreads easily. But it's our job—at least my responsibility—to do the work, to study and research before posting anything. Sometimes I can be wrong, and that happens. If it does, I own my mistake, and that’s okay as long as it doesn’t happen too often.

MR: Where do you get your expertise and authority from?

LY: It’s really about pop culture. Everything in pop culture. From the fashion in Kill Bill—the iconic Moschino coat—or in Inglourious Basterds, the plaster cast with the heel. That was insane, and there's so much to explore in fashion there. Even artists like Lady Gaga and David Bowie—there are too many to count. Everyone taught me something, because these people were actually saying something through clothes, and that was something I didn’t know was possible. I grew up doing that, and a lot of delusion gave me the confidence to start talking about it. Everyone should be a little delusional.

MR: What do you mean by delusion?

LY: I think I put myself higher in my head than I actually am. Like, “I know better than you,” but I don’t really. I think you need a bit of delusion to do anything, to put yourself out there.

MR: And now that you got big online, how do you measure your impact beyond Instagram or TikTok reactions?

LY: It’s actually insane. For example, since I started shooting backstage videos with the iPhone 4, a lot of people have started posting like I do. Recently, I was in New York for a show, and there were like ten kids coming up to me with an iPhone 4, and that was really amazing. It felt even more like I’m here to change something, and that together we can do something cool. Now, with that impact, I’m trying to bring back lipstick for men, because in a society that’s heading towards fascism again, we have to be even more daring, be ourselves, and own it. Lipstick is a mark of that, I think. And as a man, to wear lipstick is punk. So, let’s be punk.

MR: Talking about being punk, do you think dressing well is part of the job? Can someone critique fashion without really engaging with it?

LY: It’s hard. I never really understood when people who talk about fashion don’t dress well. I was always suspicious of that. But again, everyone has their own taste. I think I love to play with my body and my style like a canvas, trying to explore parts of myself through that. Can you be a good critic of music without having a taste for music? I don’t think so. So, it is perplexing when I see someone who’s a journalist or a critic and they dress like shit. I don’t think I would trust them, but some people would probably say I dress like shit too, so I guess it’s very individual.

MR: Many shows nowadays seem to be designed with “Instagrammability” in mind. Do you think we’re in an era where fashion shows have become more about going viral than craftsmanship?

LY: That was definitely the case a couple of years ago, but I think we’re returning to craftsmanship. Just the idea of Matthieu Blazy going to Chanel represents that—a new wave of craftsmanship, the artisan. Him taking on the biggest job in fashion means something in this industry, and it shows that how we view fashion is shifting. I think we’re going back to wanting good clothes. We want clothes that make you feel something, not just a crazy set design or a celebrity in the front row. That’s what I see from my audience. I know they care about the set design or the big celebrity, but it all has to be linked to the collection. Otherwise, they wouldn’t care.

Even the last Dior collection by Kim Jones was especially good because he didn’t rely on any logo or print. Yes, there were Kate Moss and Robert Pattinson, but it felt like it was going back to couture—especially couture for men—and that, in itself, is a sign that we’re returning to craftsmanship.

MR: Could it be that we’ve gotten so used to being hyper-stimulated by shows that were so crazy, that now people are actually moved by the simpler things?

LY: Yes, it’s a return to minimalism—stripping away everything, every gimmick, everything that’s too much, to get back to a sense of truth. The artifice can take away from that truth. Personally, I love the spectacle when it’s justified, but it can definitely create a distance between the audience and the message of the collection for some people. And I totally get that.

MR: You talk about making fashion accessible to everyone, but high fashion is built on exclusivity. How do you face that paradox?

LY: I don't care [laughs]. I think it’s amazing that a kid in Rwanda can watch a Chanel show. Why not? Let’s democratize fashion. It used to be so exclusive and elitist—and fuck elitism. I’m here to tear down this idea that if you work in fashion, you have to be mean, that you don’t have to laugh or show emotions. Let’s cut that shit.

Plus, I don’t think it’s necessarily about being able to buy the clothes. I never could afford the clothes I really wanted growing up, but I still cared so much about fashion. They’re not selling the clothes, they’re selling the fantasy, the dream—and that’s what I care about most in fashion. It helps you escape reality, and you can do that by creating characters, creating stories for yourself and for the brand. You don’t need millions to do that—you can do a lot with just a few dollars at a thrift shop. Who cares? It’s about the idea of creating personas, escaping through fashion. Once you see it as art, as I do, you won’t see it as exclusive. Sure, a Monet costs millions, but you don’t need to buy it to appreciate it. You can look at it, and that’s enough. That is beautiful.

MR: Do industry people ever look down on you for not coming from the “right” path and not having done the right schools, internships, etc?

LY: Yes, of course. But that’s part of this industry, and that’s why we have to change things. A lot of people still look down on me, but I don’t care. I really don’t. I’m going to prove them wrong. It’s also a drive. For some, it can be an obstacle, but for me, it’s a drive to prove them wrong—and without that, I’d still be in my old cramped apartment.

MR: Do you think that the old-school fashion critic still exists? Can anyone in this industry afford not to have an online presence?

LY: I think people in the past did it especially well, like Cathy Horyn and Suzy Menkes, even though she’s apparently a “Trumpy” now. But I think you can still do it nowadays; it’s just way more difficult.

MR:Your radical honesty works because you’re independent. But can people inside the system—editors, creative directors, designers—get away with it?

LY: It’s very complicated, and I struggled with that a lot working with certain publications and maisons. The advertisers control everything; it’s the business model. I respect it, but I refuse to play their game. I think it’s a privilege to say what you want. It’s the most important thing in the world, and I would rather go broke and know that I’ve spoken my truth than lose my integrity to the demands of this or that publication.

Credits

- Text: MAX ROSSI

- Photography: AMEYA EDISON STEPHENS

- Fashion: PAULINE ABADIA

- Talent: LYAS

- Makeup: AXELLE JOVANOVIC

Related Content

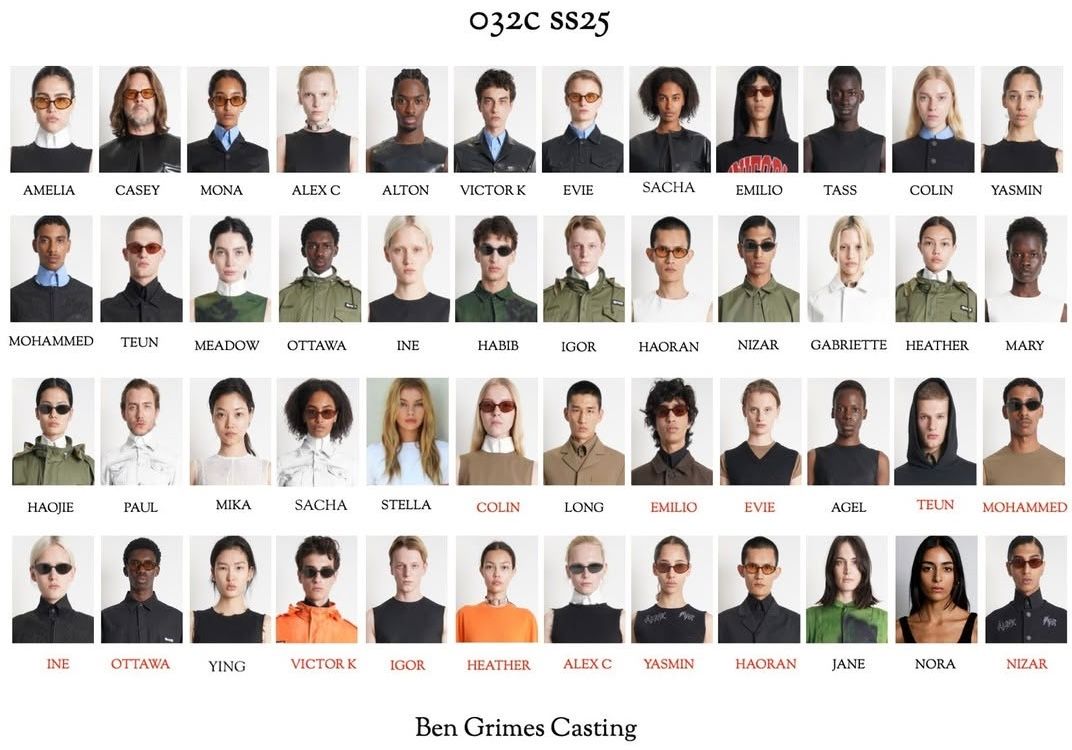

How to Cast for a Runway Show with Ben Grimes

Made in Heaven: Gerrit Jacob

How To Produce a Runway Show With Etienne Russo

Eckhaus Latta Prefers Glitches To Filters

Transcending Traditional Fashion Discourse with Massimiliano Giornetti

SUSPICIOUS MINDS BTS: 032c Readytowear Fall/Winter 2025

SUSPICIOUS MINDS: 032c Readytowear Fall/Winter 2025

MONA TOUGAARD in “The Whole World Glows Outside Your Eyes”

The Erotics of the Nerd

KIM JONES Interiors: A Room of One’s Own

MATTHIEU BLAZY’s BOTTEGA VENETA: Coherence in a Fractured Moment

Officecore with Gucci