WIP CARHARTT

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our issue #30.

Swiss clothiers Edwin and Salomee Fäh discovered Carhartt during a trip through the United States, while researching workwear for their jeans store in Basel. It was then that they began crafting their European re-conceptualization of the legendary Midwestern workwear brand, under the banner of Carhartt Work In Progress. With a name that suggests its own spirit of experimentation, it takes the no-frills mentality of union-made apparel to an expanded context. Its first set of marketing guidelines from 1994 reads like an anti-marketing manifesto: “No jeans. No fashion or department stores. No high street.”

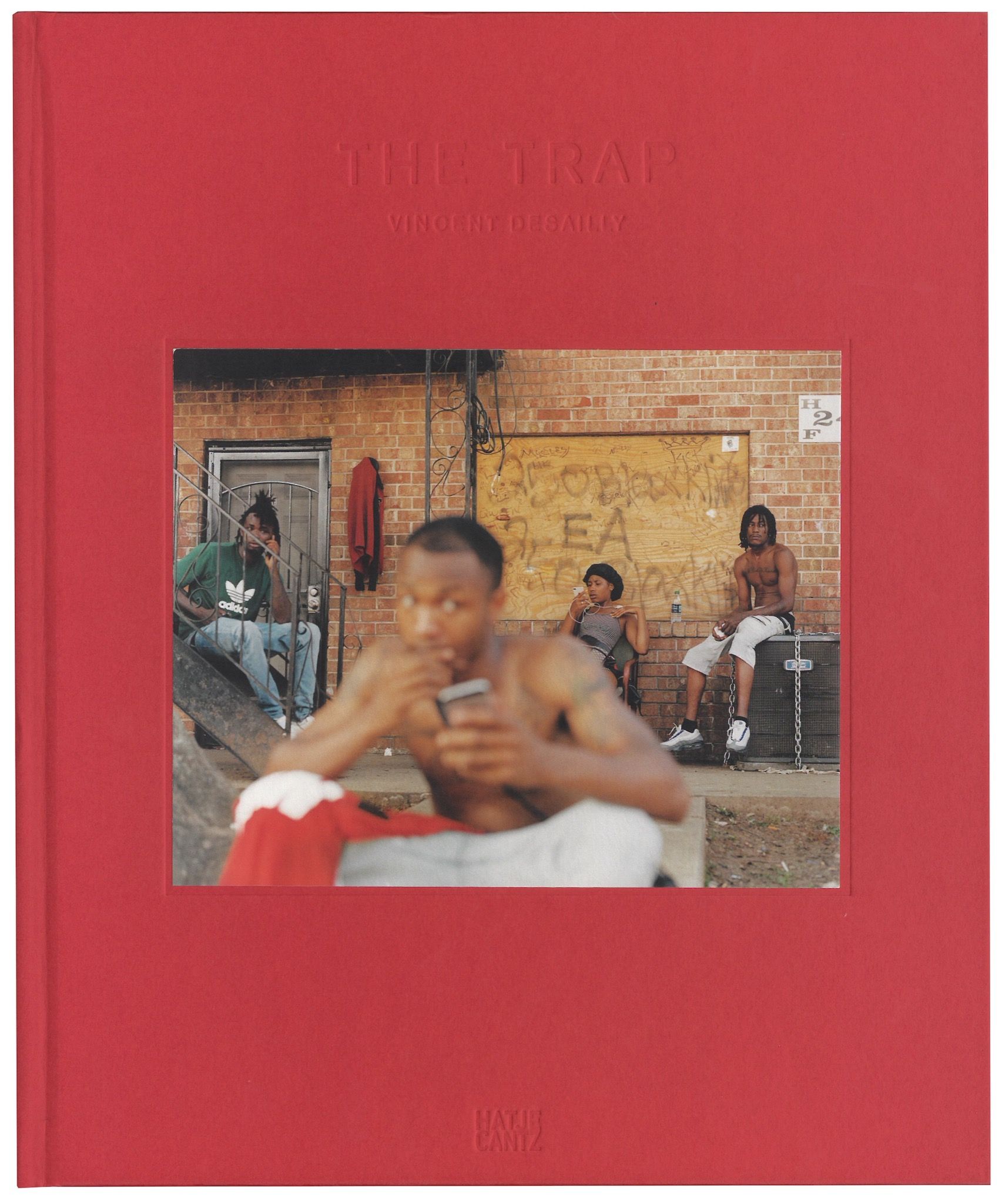

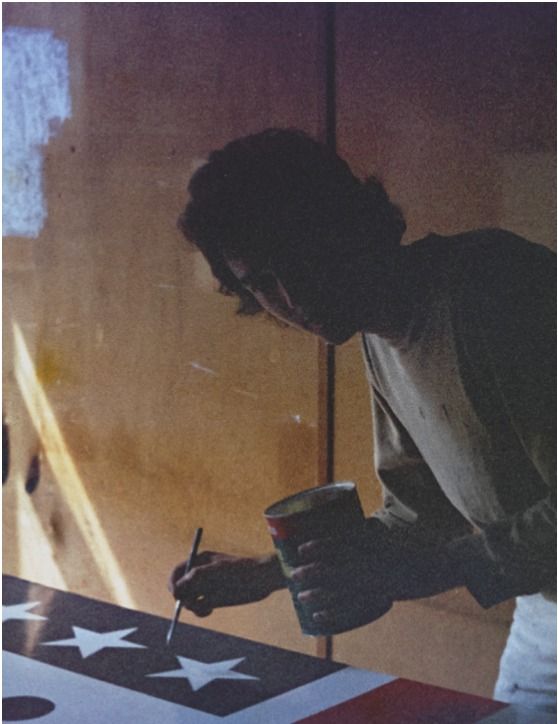

In the upcoming book Work In Progress — The Carhartt WIP Archives, Gary Warnett delivers A HISTORY OF THE WORKWEAR BRAND’S GLOBAL INFILTRATION into fashion:

Workwear became a true class statement in the 1920s, when the term “blue collar” was coined as a blanket name for manual occupations. From the beginning, it evoked images of denim or chambray as opposed to the crisp white collar of the office worker. Even at this time, working class life was heavily romanticized within the DNA of workwear brands such as Carhartt, which was founded in Detroit, the capital of America’s “Rust Belt,” in 1889. Putting in the necessary toil reflected the everyman, the American Dream, honesty, and to some degree the deification of the “self-made man” that typified consumer consciousness.

Carhartt’s migration from the construction site into the world of fashion took place through streetwear. In the 1980s – alongside army surplus items – workwear became part of hip hop’s uniform. In images of NYC’s fabled Latin Quarter club that date back to 1988, Carhartt is pictured alongside Louis Vuitton. The cover of rapper Diamond Shell’s 1991 album, The Grand Imperial Diamond Shell, depicts him in head-to-toe Carhartt brown duck. He wasn’t alone. With an uncompromising sonic shift, spartan looks suited the hip hop sound and Carhartt was heavily worn on both coasts. With loose, oversized attire in fashion, workwear’s full cuts fit in with ease.

By 1993 – a significant year for hip hop’s breakthrough into popular culture – the fascination with blue collar anti-fashion had attracted media attention. Skate style was steeped in oversized fits inspired by the era’s hip hop. There was a need for clothes that offered rugged protection against concrete. For skaters, a visit to San Francisco was practically a pilgrimage, and the working class reality of the area was reflected in local attire. Iconic spots like EMB – the birthplace of Thrasher magazine and Antihero – was also the place where workwear took root.

The anti-fashion appeal of workwear operates in dual directions. Some favor the severity of the aesthetic: stark, simple products that are expressive, but that operate contrary to the fuss and pomp of conventional fashion. Others gravitate towards its timeless look: with staple silhouettes barely changed over the decades, and garments that develop greater personality with each wear. Workwear is the antithesis of fast fashion and planned obsolescence.

Carhartt collaborations have manifested these cultural connections as limited edition objects. At its most logical, collaboration culture concedes that the best of both worlds is better and that there is little point reinventing the wheel if there is already a factory making it to a very high standard. For all that physical and cultural travel, wake up early enough, catch the subway, and you will see workers en route with Carhartt gear on their backs – no gimmicks, no irony, no trends. Just workwear put to work.

Work in Progress – The Carhartt WIP Archives is published by Rizzoli and will be released in October 2016.