Burberry: Berlin Review

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our issue #43

Coats are made for the weather

In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Thorstein Veblen suggests that clothes are not worn to protect us from the weather. Instead, they are supposed to show that we do not have to engage in labor. If we were the farmers or mechanics, we would need protective gear that would be covered in mud or grease, which would signify our need to work for money. For everyone else, clothes, Veblen holds, are there to demonstrate that we are members of a class that has the means to relax and can purchase new garments as change in style demands. He writes, “the standard of reputability requires that dress should show wasteful expenditure; but all waste is offensive to native taste.” Real taste, then, is about having things that last.

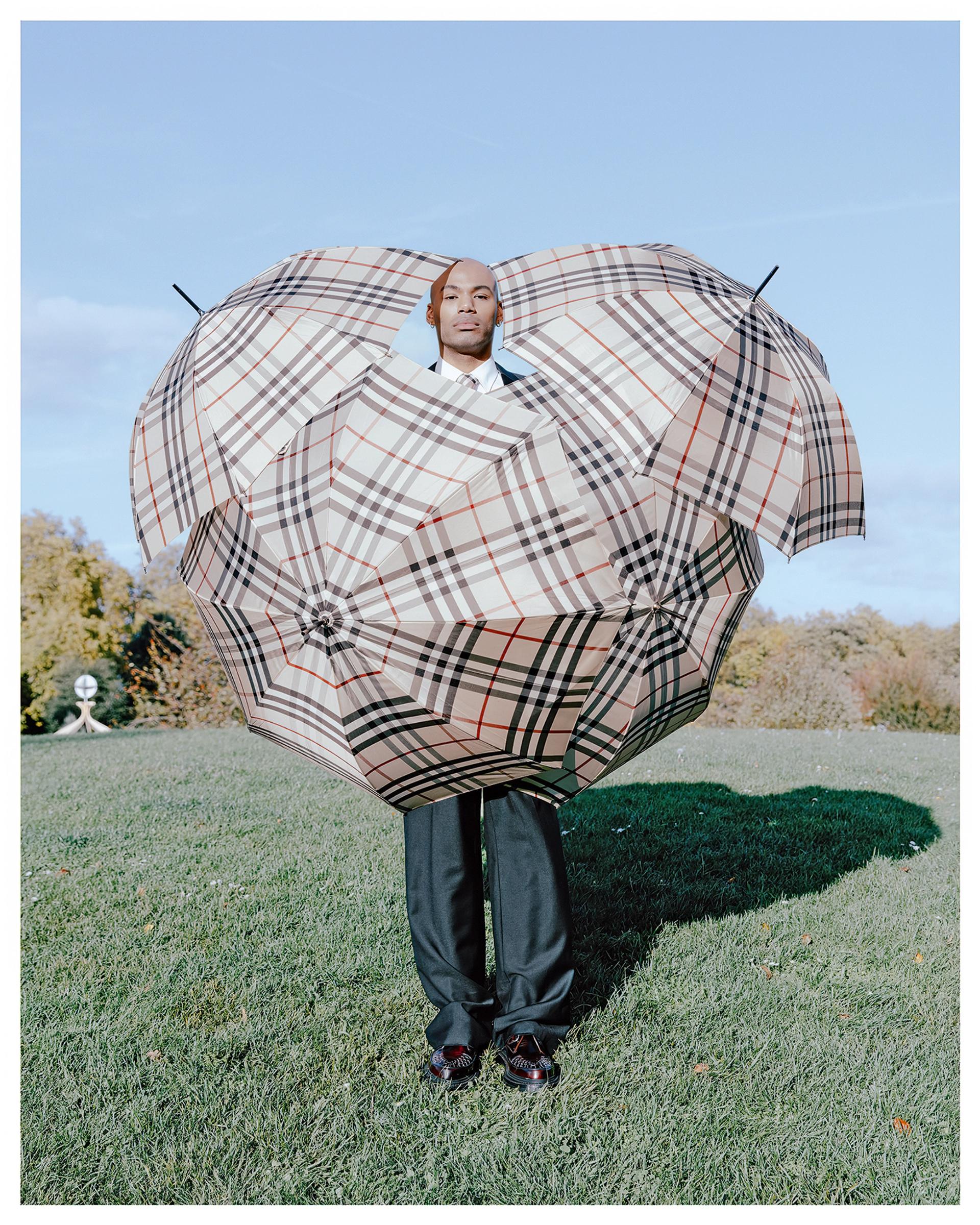

Which for me is somehow synonymous with Burberry. The checkered inner pattern and straw-colored outer shell of its trench coats are timeless, both in the sense that they have been around for more than a century—an eternity for trends—and that they have never felt dated, have always been updated, while retaining their relationship to legacy. Most importantly, Burberry coats last forever; they were designed to endure hardship. Anecdotally, I can still see the beige Harrington jacket of a wealthy high school friend that he had inherited from his father, and it is likely that one of his children will come by the jacket. There will be more stains from the past, but it will never not suggest a certain prosperity. After all, the Royals wear Burberry.

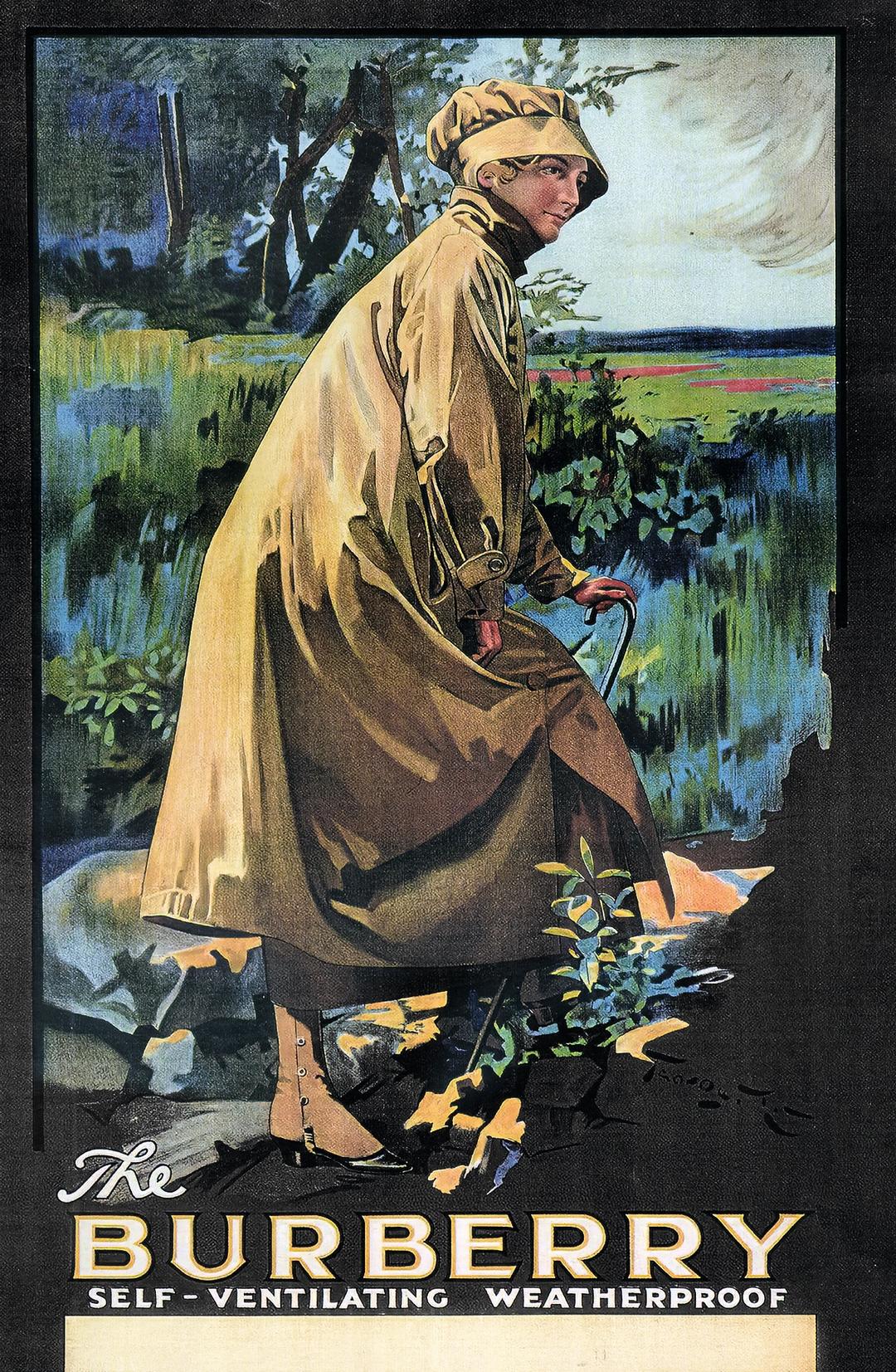

The brand might as well mean aristocratic, yet its origins are actually in workwear for the working class. Thomas Burberry’s first customers worked in agriculture, and the brand’s originator designed his clothes to brave the British weather. Alexander Fury writes in Burberry that “Thomas’ own nascent experiences, wandering fields and meadows in his rural upbringing, forged his idea of what British people need from their clothes: practicality, pragmatism, a shield from the elements that are characterized as ever-changing and uncertain.” Burberry, then, is a remarkable twist on Veblen’s thesis, as the company’s coats are supposed to be covered in mud, road dust, and water—Burberry historically has designed clothing for better riding, fishing, and motorcycling—but are nevertheless bought and respected like other clothes of wasteful expenditure. Somehow Burberry threads the needle and belongs to the leisure class and all others.

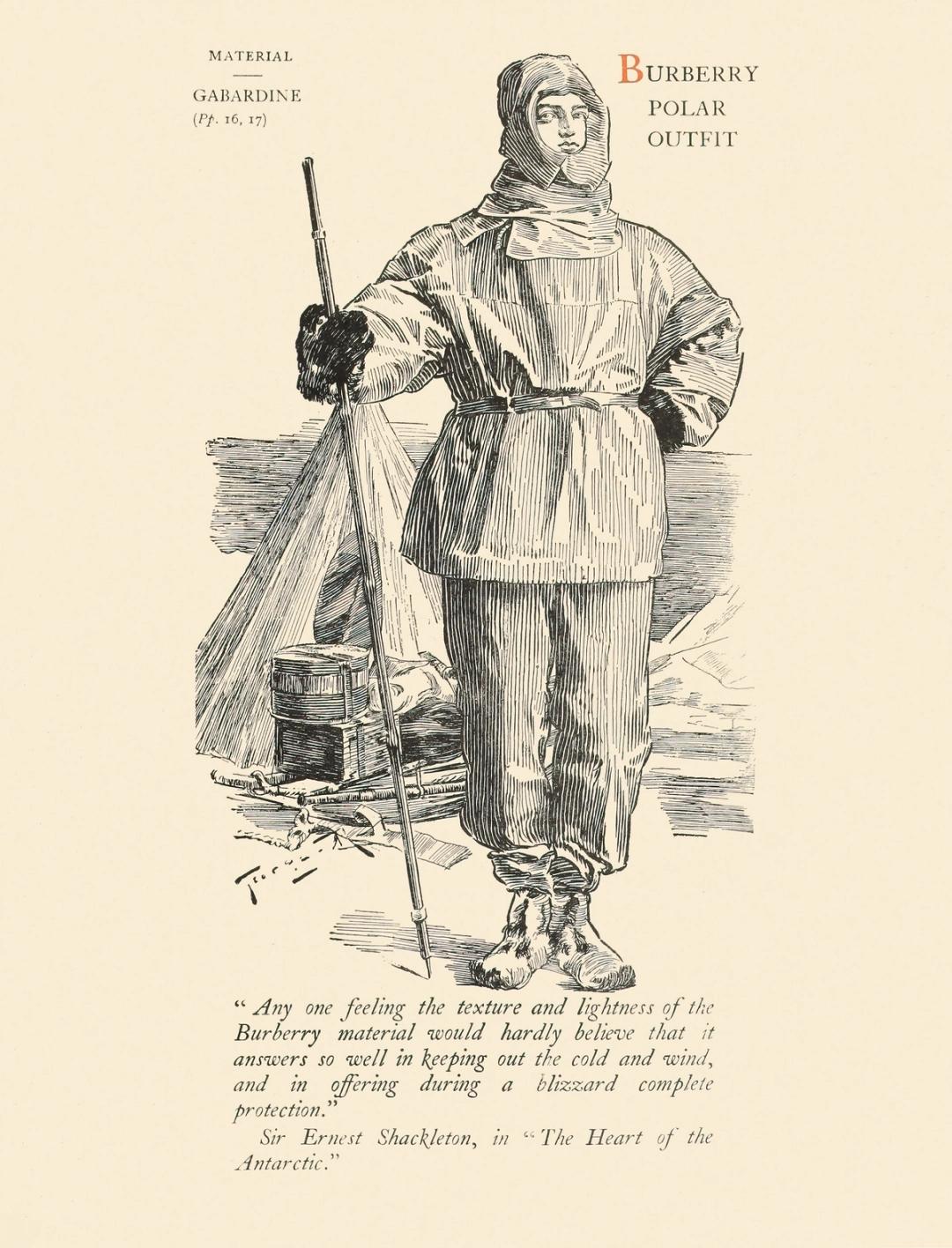

How the brand’s multivalence could come to be is something the reader of Fury’s Burberry can discover, as the author excavates the history of the house while demonstrating its mutating cultural significance under the guidance of Christopher Bailey and Riccardo Tisci, for example, or its current creative director, Daniel Lee. Despite its at times nauseating ad-speak and clichéd diatribes on “Britishness,” Burberry is a fascinating foray into the brand’s history, touching upon Shackleton’s Antarctic expeditions; such celebrities and artists as Beyoncé, Marina Abramović, and David Hockney; manufacturing techniques; and the importance of weather for clothes.

Burberry is published by Burberry (2023)

Credits

- TEXT: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

The Art of Collecting Chairs

Cobrasnake: Berlin Review

Hysteric Americans: Berlin Review

Artists as Messiahs: PETER FEND

An Internet the Size of a Room: Berlin Review

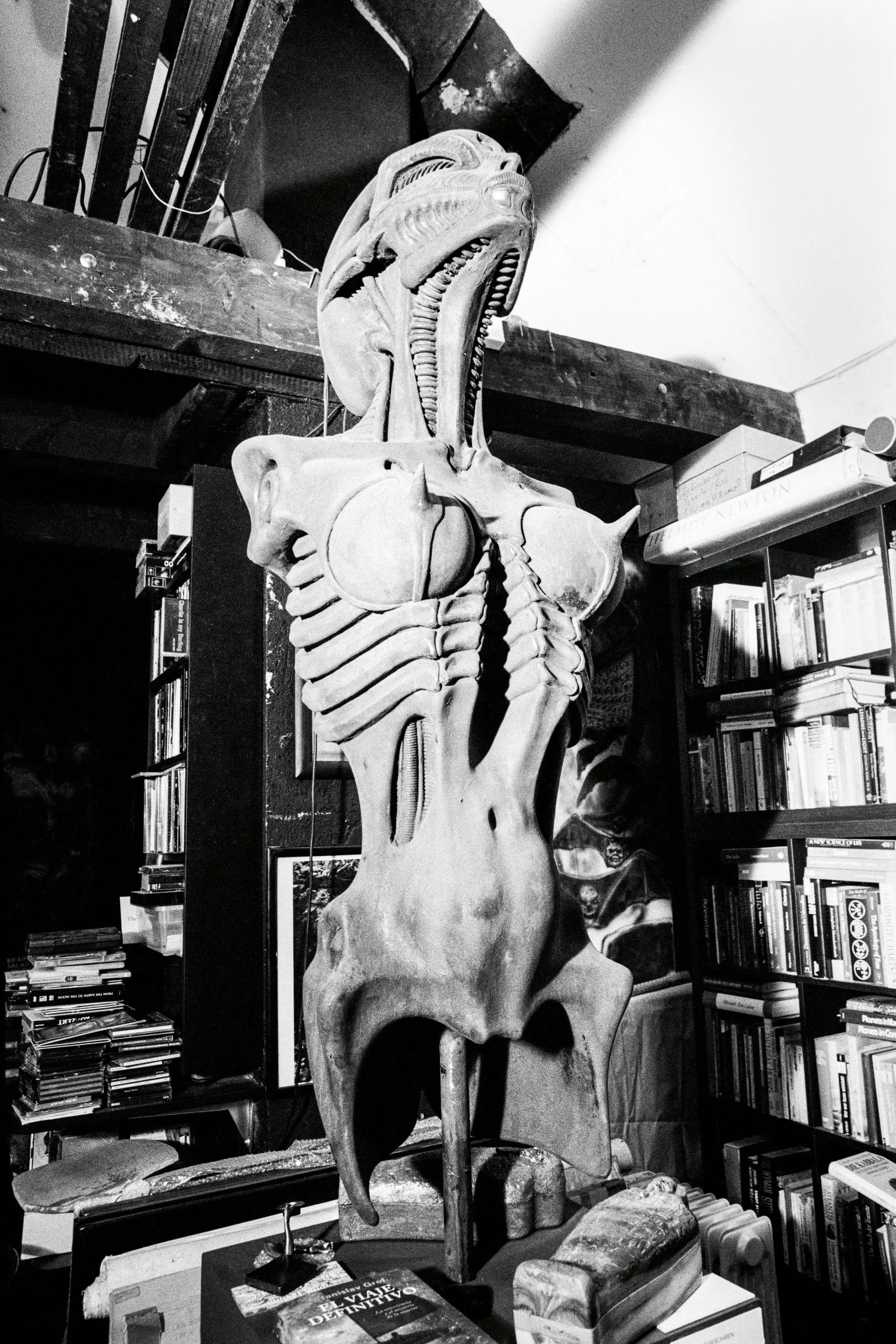

Libidinal Teratology: HR GIGER by CAMILLE VIVIER

Ice Cold: Jewelry as Political Embodiments

The Road to Burberry: An Interview with RICCARDO TISCI