DAVID CRONENBERG: The Wax Anatomical Model

|Shane Anderson

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

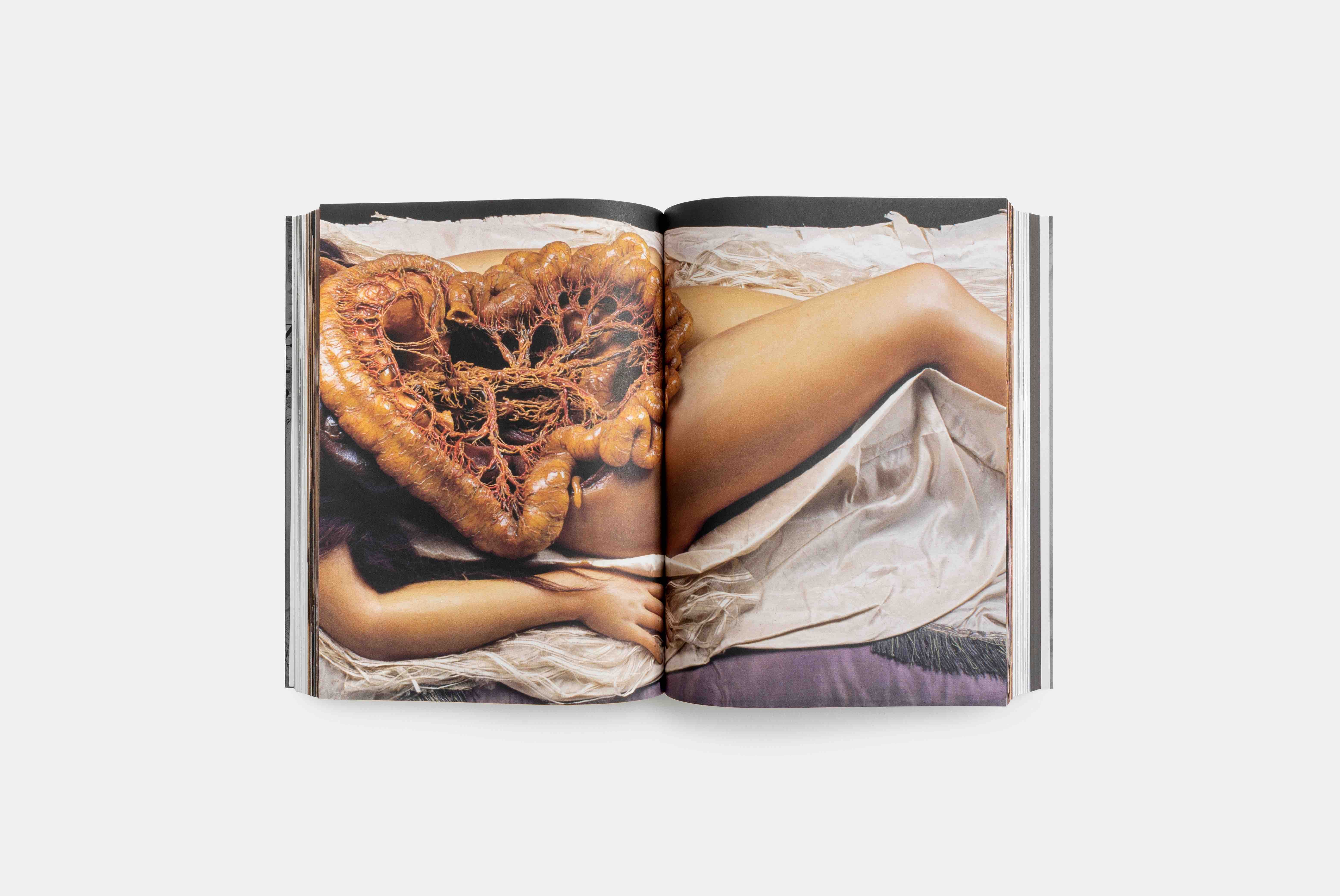

Inside the Museo La Specola are anatomical mod-els that were created sometime during the 18th and/or 19th centuries. These wax sculptures were praised by surgeons at the time for the knowledge they provided about the workings of our organs, and they were also esteemed by writers. Stendhal found them instructive. Goethe admired their blend of art, science, taste, and technique. And yet, there have also been detractors who find them morbid. Herman Melville, for instance, thought “they were horrible and nauseating” — a characterization that is certainly justifiable. There is some-thing repugnant about the yellowish hue of wax intestines with melted fibers mimicking arteries, or life-like twin fetuses — their necks wrapped with umbilical cords — nestling in a womb that has nobody attached to it, apart from truncated, hollowed thighs.

Finding the beauty in dismemberment and disgust has been the lifelong obsession of David Cronenberg, who has made more than 30 films operating in the realm of nightmares. eXistenZ(1999), for instance, is about a game designer on the run from assassins and features scenes with solid objects being swallowed by scarred orifices, and rotten food and loose teeth being fashioned into a weapon. In The Fly(1986), scientist SethBrundle becomes a hybrid fly–human monster who uses his corrosive neon-blue vomit to incapacitate an enemy doctor. The film also features a dream about giving birth to maggots and a baboon that’s turned inside out after being teleported.

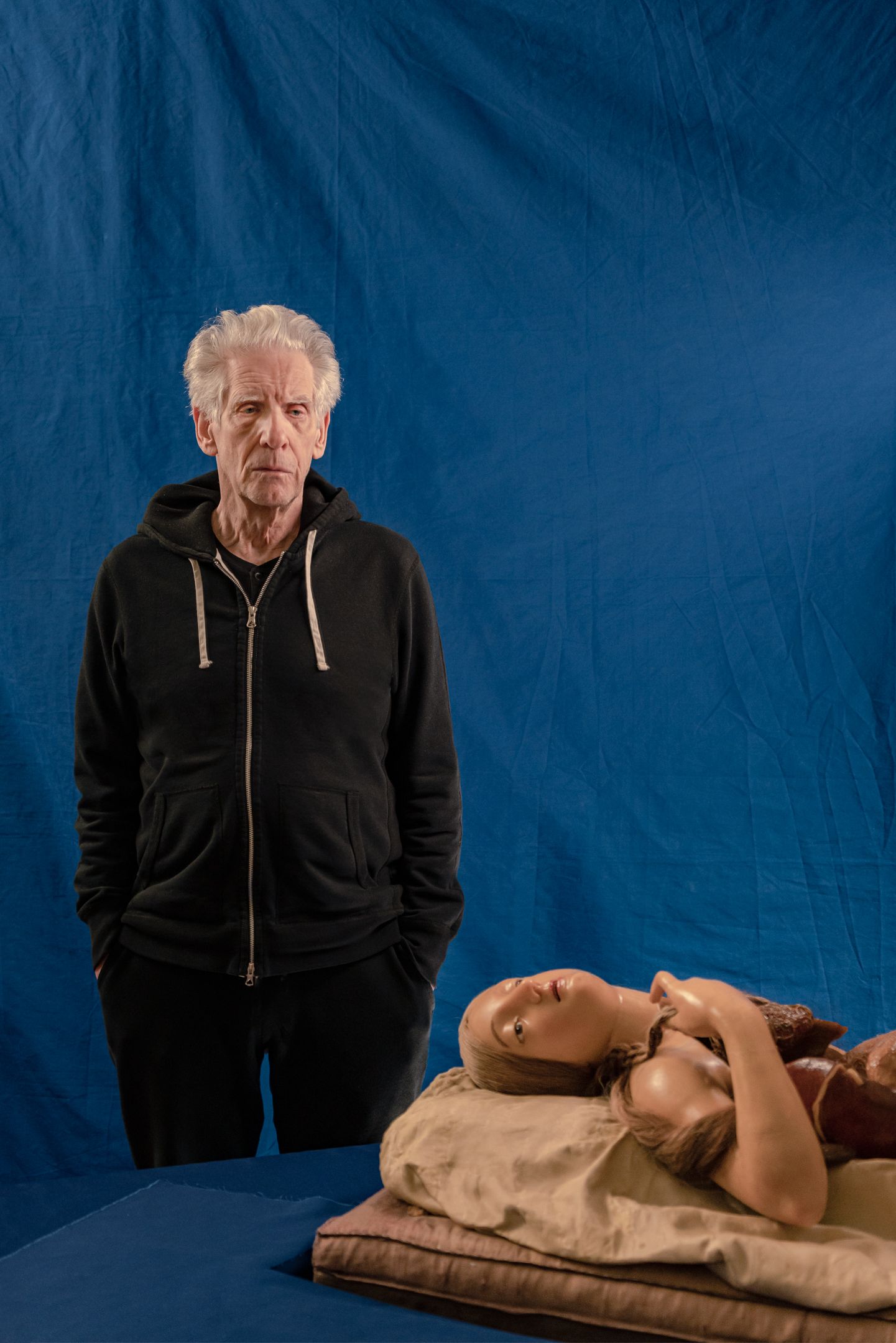

You could say that Cronenberg’s fascination with the body’s possible mutations shares an affinity with the Enlightenment surgeons who sought to unlock the mysteries of the human corpse.Cronenberg, whose films are classified as “body horror,” is interested in what the body is and can do, and the theme of dissection and mutilated body parts often plays a role in his work. As such, it makes sense that La Specola, which is part of theUniversity of Florence’s Museum of Natural History, teamed with the Canadian filmmaker for the exhibition “Cere Anatomiche” at the Fondazione Prada. In the exhibition, they displayed four of these female wax figures; nine body sections from the obstetrics group; and 72 drawings in tempera, pencil, and watercolor detailing various organ and nerve systems; as well as a new film by Cronenberg — a grainy investigation of the exhibition’s works, its look somewhere betweenThe BlairWitch Project and softcore porn. Throughout the exhibition, focus was placed exclusively on the fe-male sculptures and on how women’s bodies were represented in a “gender-based appraisal” — what-ever that means. Cronenberg suggests in the exhibition catalogue that the wax women do not “display pain or agony,” but instead seem to be “in the throes of ecstasy.” There’s something dehumanizing and objectifying about his assessment, which is of course weird, as the figures were never human to begin with. But this gendered standpoint never gets fully addressed. Instead, in typicalCronenberg fashion, he wonders: “What if it was the dissection itself that induced that ecstasy, that almost religious rapture?”

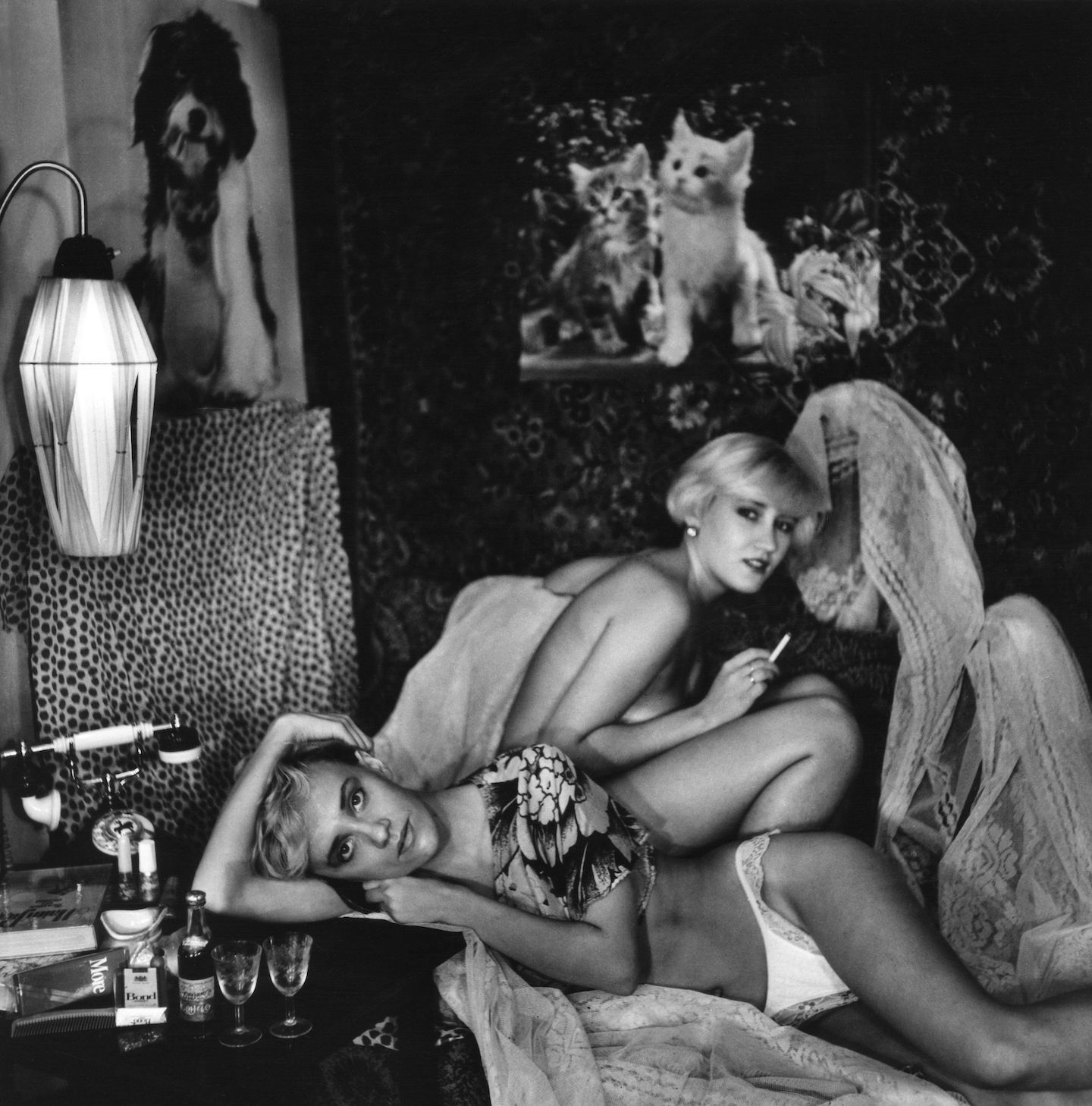

This guiding question is evident in many of the catalogue’s 126 closeups of the figures, where in their heads are tilted back, their lips slightly part-ed, and their calm, half-open eyes stare into the distance. Their facial expressions, juxtaposed with images of livers, kidneys, and ribs, resemble such Renaissance works as Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa (1647—52), which upon completion was criticized for the saint seeming to be engaged in a sexual experience, rather than a religious one. Similarly, La Specola’s wax figures are highly sexualized in the catalogue. Bare thighs, pearl necklaces, lace bedding, and hands fingering strands of hair evoke shoots for Playboy from the 1980s, despite the subjects’ entrails being visible. It’s a mixture of sexuality and gore that does what the best of Cronenberg’s films do: they make the monstrous alluring. Sadly, this achievement can’t be attributed to the rest of the catalogue, which is rounded outwith 28 conversations and essays on the museum, the collection, Cronenberg’s films, and wax figures. If you’re not interested in the his-tory of anatomy, then much of the book’s first half can be skipped. One highlight, though, is Georges Didi-Huberman’s “Nudity Opened: The Venus ‘of the Doctors,’” in which the philosopher meditates upon the (sexual)impurity of Florentine humanism. After reading the essay, I couldn’t help but wonder: Is Cronenberg a modern Marquis de Sade or just a pervert?

Anatomical Waxes: La Specola Di Firenza is published by Fondazione Prada (2021).

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson