WILL BENEDICT’s French Cuisine

|Shelly Reich

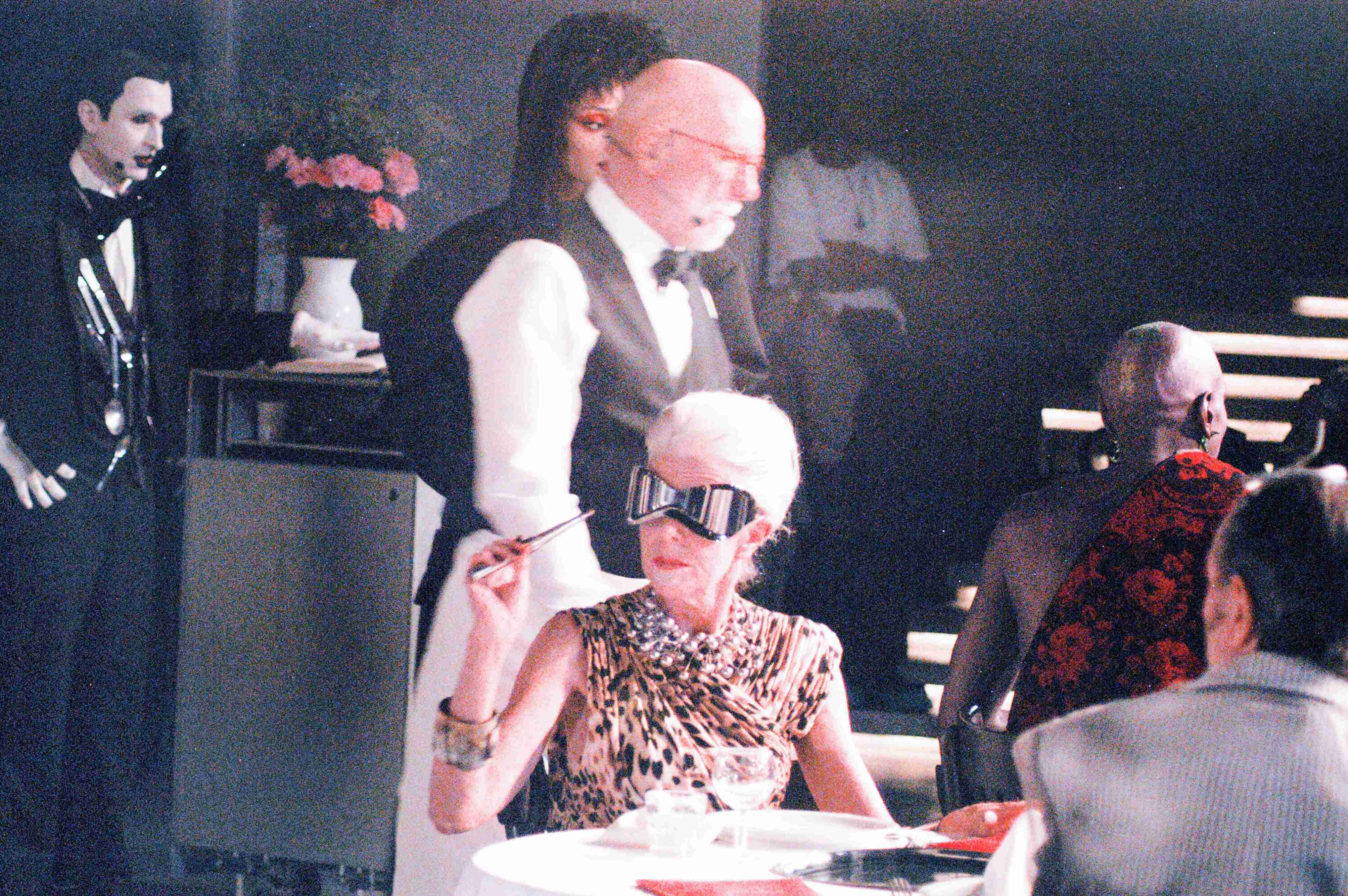

This fall, artist WILL BENEDICT staged Pandemonium, a one-night-only avant-garde musical theater piece at the Pinault Collection in Paris. Satirizing the vivacious culinary and nightlife scene of the city, Benedict orchestrated more than a dozen performers, each embodying the flamboyant personas commonly found in these establishments.

Federico Nessi, known for his occasional karaoke performances, brought the Maître d'hôtel to life with a dash of Klaus Nomi’s Cabaret charm, while Agnès Tassel captivated onlookers, adorned in a Michael Kors cow-print trench. Infused with an unmistakable American touch, the artistic milieu of Pandemonium dared to disrupt the status quo. Benedict's masterful creation intertwined meticulously curated French cuisine with the experimental accompaniment of his long-standing collaborators, Wolf Eyes.

SHELLY REICH: Pandemonium seems to blur the lines between art, music, and theater. How did you envision the musical coming together?

WILL BENEDICT: Well, it took 30 people to make: Pierre-Alexandre Mateos and Charles Teyssou, the curators who put it together and produced it, Delphine Gaborit, the choreographer, the 12 singers and dancers and performers on stage, Myssia Ghosn the stylist, Jean Dorthu hair, Hugo Villard makeup, and Alexia Cayre who developed the looks and introduced me to all these talented people. The level of professionalism and expertise in Paris is genuinely incredible.

I was talking with Wolf Eyes last night and we were thinking about doing a version of the performance in Detroit, but in Paris we were tapping into the rich resources of professionals within the fashion industry here, so in Detroit we thought we might be able to work with Backyard Wrestlers, techno DJs, and community gardeners. You have to work with what’s there.

SR: I also see that art musicals or multimedia artists creating musicals seems to be on the rise. Why do you think that is?

WB: I don't know. I didn't realize people were really working on musicals. Ei Arakawa made this insanely ambitious and complex musical for the Berlin Biennial in 2016. The rehearsals must have been epic. I can’t really imagine. Our rehearsals were a total disaster but as soon as we went live in front of an audience everything went perfectly. You know, I don’t have a lot of experience with this kind of thing. But maybe that’s the way it works. A sort of frying pan logic.

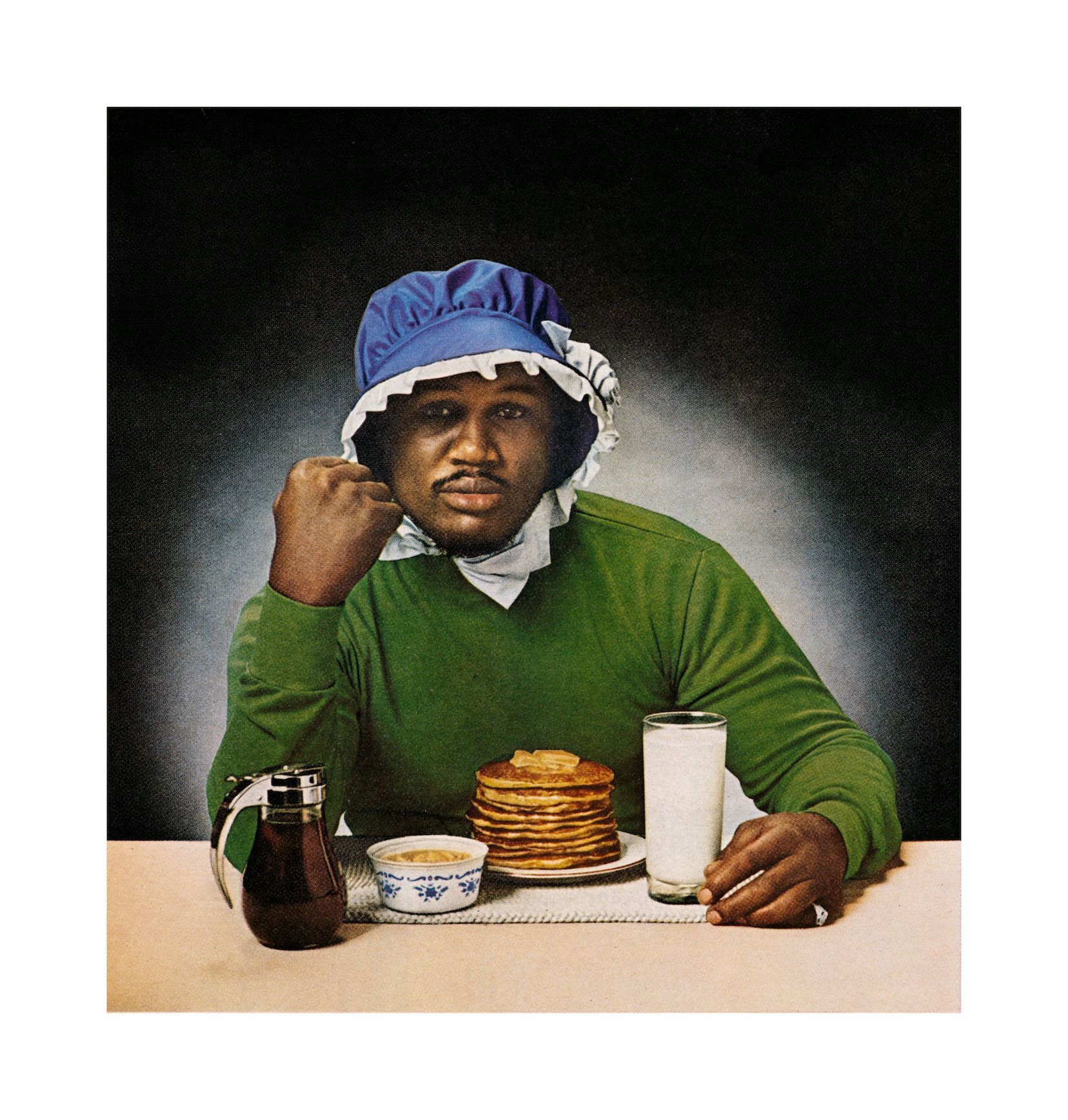

SR: In the musical, there’s a juxtaposition between traditional French cuisine and contemporary internet culture, such as mukbang videos. How does this contrast between high and low culture play out in your practice? And what messages or critiques do you aim to convey through this exploration?

WB: I made a couple of seasons of a TV show called The Restaurant with Steffen Jørgensen. I am interested in the social and political dimension of food, its fundamental qualities, and the necessity for it. Eating is one of those things that you have to do. And so, I think that it’s something important to pay attention to.

O'Tacos, for example, is such an interesting phenomenon in France. It’s become a lightning rod of difference in the country. Young people in the suburbs invented a taco that has offended every Mexican or any person who’s ever eaten a taco before. It has also offended the national character of France. I admire it politically. It aggravated a culture that is very sure of itself. And that sort of confidence in being correct or right is a bit dangerous. That said, if I had to just reductively compare French to American food culture, I would have to say that America is wrong. Americans have such a brutal relationship with food.

France’s ties to agriculture aren’t just about good food or responsible production though. It’s also entwined with its colonial past. Napoleon III had this grand vision of turning Algeria into France’s agricultural breadbasket. If you were waiting for a meeting with the emperor in around 1860, you would be waiting in this massive antechamber and on the wall would have been this very large painting of Algerian laborers harvesting a field of wheat. So whatever business you had with the Emperor, the Emperor was clearly saying that this was his plan, that in order for France to fully industrialize he would be transforming Algeria into France’s agricultural center. 50 or so years later, France takes control of and helps define the borders of Syria to secure their cotton trade routes. Cotton being more significant than oil at that point. So, food and fashion. This is not a long time ago.

SR: What do you think about how artists are labeled in the art world and the shift towards art becoming more professionalized instead of exploratory like it used to be?

WB: The art world often prefers clear labels: a video artist, a painter, or a multimedia artist. They coin terms like Arte Povera or Kontextkunst as marketing.

It’s not like in the good old days, everybody thought for themselves. In the 60s, everybody made minimalism. Which is very silly, and very sweet in a way. I went to a talk by Michael Asher once and he was showing his early works which were very modest explorations of what we could call minimalism. And he really emphasized that everyone was doing this and that he had just made them to decorate his apartment. I found that so charming.

Now, pursuing art feels as professionalized as becoming a doctor. I’ve seen this professionalism grow in the past 20 years, and I don’t know if it’s the best direction we could be taking.

SR: The cast in the musical includes figures such as the artist and musician Sofie Royer and artist Lukas Heerich. Could you share more about how you developed these characters? And what was the casting process like?

WB: I did the casting of the main characters—the singers and the chefs, including Lukas and Fabian Marti, I mean those guys have looks for days, so that’s why I cast them. But then we needed to figure out all these dancers and everyone else. I wanted amateurs, real people. And the casting director Rachel [Halickman] came through with remarkable people. I think that there’s a shortcut to a sort of explicit humanity in being an amateur. A kind of vulnerability. There’s a spirit to being an amateur that you can read from the audience, and I wanted that look. I wanted that feeling. My favorite dancer, Agnes [Tassel], was probably the least comfortable with the choreography which involved a lot of dancing in unison. She was very suspicious of everything. And the look of suspicion and confusion on her face was perfect. I was living for her performance.

We did have one professional dancer, Andre [Atangana] and he could bring that contrast, he could make big moves and he could lead people a bit. Dancing in unison isn’t so easy. But the cast built bridges through their differences. Which is, I think, where the magic happened.

SR: Your long-term collaborators Wolf Eyes provided live music for the musical. Could you share the origins of this collaboration?

WB: I had a show at the Bergen Kunsthall [in 2014]. For the first time in my life, I had this really huge budget. I wanted to make a video with the artist and journalist David Leonard, whom I’ve known since I was a kid. He’s an artist type who left art behind to become involved in real life. He dropped out of art school, moved to West Virginia, got a journalism degree, and became a local affiliate newscaster. He would go on the news and do these reports about SARS being in the beards of shopping mall Santa Clauses and other stories like that. So, again, I wanted to make a movie with him, and then it was very obvious to me that I wanted Wolf Eyes to do the soundtrack. We made that video, which is called Toilets Not Temples, and then we started making music videos. Sometimes Wolf Eyes would ask me to make one and sometimes I’d ask them. And it just kept going. But the emphasis is that my work really is about working with other people.

Nate [Young] from Wolf Eyes is so receptive and open to trying stuff, he’s not insecure about what he makes. We can talk through the sounds and say why this tiny little wiry sound that’s buzzing doesn’t work or why the bass has to be more profound. Those are exciting conversations. It’s extremely fun to have that kind of relationship, where you are able to talk about very detailed aspects of what a sound or thing is. I would love to just do that for the rest of—like, that’s the job I want. That’s the fun thing about being an artist, you can make the job you want.

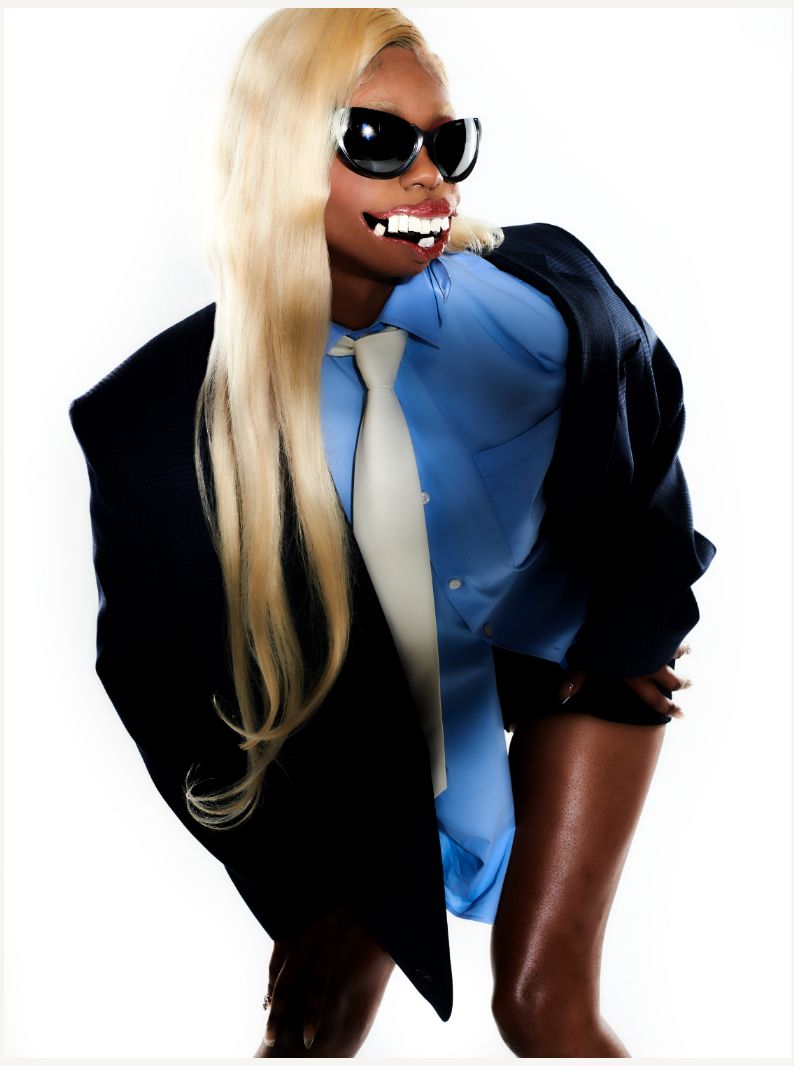

SR: You also did a project for Balenciaga. Could you tell me about that?

WB: The Balenciaga video was so fun to work on. That was actually the closest I’ve felt to this musical that we just did. That type of work, attention to detail, working with such a large crew—it’s really exciting. I love it.

I think Balenciaga already knew they wanted to do a newscast. The same way that Pierre and Charles knew they wanted me to do a musical about a restaurant. People come to me with an idea of what they’d like me to do a lot of the time. I kind of like that. I don’t know if other artists have that experience, but it’s very common for me.

So, Balenciaga wanted to do a newscast. And they had maybe seen Toilets Not Temples, which is kind of a news documentary, and which features a newscaster and a reporter on the scene. And then I did a video called I AM A PROBLEM, which is an alien being interviewed by the journalist Charlie Rose. So, I think Balenciaga was like, “Oh he makes news programs.” That’s how I got the job. At some point while we were working on the Balenciaga video, the time difference was very drastic between Detroit, where Wolf Eyes was, and Maui where I was. Nate and John [Olson] would send me bits of music and I would try to see if they worked for the video we had planned. Every morning I would wake up and I would go out on the balcony overlooking the ocean and palm trees and put my headphones on and listen to some of the harshest fucking music you’ve ever heard but which is also extremely melodic and beautiful and quite romantic in a way. And again, I could work that way forever and I have been trying to put myself in a position where this is what I do, just listening to what Nate sends me.

SR: What is the future of musicals made by artists?

WB: I don’t know. I have to admit I haven’t really thought much about it. I watched François Ozon’s musical Huit Femmes (Eight Women) again recently. He strikes such a careful balance between the dialogue, the songs, and a sort of naturalism to the songs. It’s as if someone could really be acting that way. I really admire that, because even though it’s super fake and the set feels like a soap opera, there’s a kind of realism to the way the songs are performed. That’s what I have been looking at, and that’s the way I see going forward. I mean, the thing with musicals is that it’s too much work. It’s too hard to do all that work for one night.

Credits

- Text: Shelly Reich

- Curator: Charles Teyssou

- Curator: PIERRE ALEXANDRE MATEOS

- Writer and Director: Will Benedict

- Music: Wolf Eyes

- Choreographer: Delphine Gaborit

- Costume Designer: Alexia Cayre

- Stylist: Myssia Ghson

- Stylist Assistant: Justine Doméjean

- Stylist Assistant: Ivana Voustsinos

- Casting Director: Rachel Halickman

- Head of Production: Graham Hamilton

- Makeup Artist: Hugo Villard

- Makeup Artist Assistant: Elora Boccia

- Hair Stylist: Jean Dorthu

- Hair Stylist Assistant: Robbe Vermaete

- Photography: Rob Kulisek

- CAST:

- The Customer: Sofie Royer

- Waitor: Mikaël Camhaji

- Waitor: George Wolfaardt

- Maître d'hôtel: Federico Nessi

- Cook: Lukas Heerich

- Cook: Fabian Marti

- Customer: Andre Atangana

- Customer: Hocine Choutri

- Customer: Nogoflani Fofana

- Customer: PZ Opassuksatit

- Customer: Maléna Sanchez

- Customer: Agnès Tassel

Related Content

ELYSIA CRAMPTON on performance: “The gift the ancestors have given me is this body”

Choreographer ADAM LINDER Dances for Hire and Disrupts Contemporary Creative Economies

Beautiful Aliens: KLÁRA HOSNEDLOVÁ

Reality TV as a Sociological Analysis: JAMES BANTONE

The Real Thing: Exhibiting the Art of the Bootleg

“It’s Important to Be Visionary Rather Than Reactionary”: Artist Hank Willis Thomas’s Aesthetics of Mass Action

“Drama—netic” by CHRISTOPHE DE ROHAN CHABOT

“Fashion Theater”: BRUNO SIALELLI at the House of LANVIN