Who Is STEVEN MEISEL?

|PIERRE ALEXANDRE DE LOOZ

Fashion’s ultimate enigma has had Vogue Italia’s cover under his spell for the past twenty years, nonstop. Considered the world’s greatest fashion photographer, a rare interview gets us just that much closer to finding out: who is STEVEN MEISEL?

In 1930 Eric Salomon photographed Marlene Dietrich in the most candid way: slumped in bed while on the phone, a pose totally and disarmingly natural. Although Steven Meisel and I spoke two Sundays in a row, we never met face to face and I was left to visualize our conversation on my own. The voice of countless magazine and advertisement pages, of cool constructed beauty; perhaps the voice of fashion itself, or at the very least its timekeeper for nearly a quarter century, materialized over the telephone and it was, like that photo of Dietrich, unexpectedly candid, grizzled, and warm.

“When I met Steven I was struck by his beauty: what a beautiful man, beautiful skin and beautiful cheekbones; he hasn’t changed!” Naomi Campbell tells me, bubbling. Another long-time friend of Meisel’s, designer Anna Sui, remembers their first encounter vividly: “He had such a presence and was so amazing to look at. I thought ‘I have to be friends with this guy right away!’” Outside his circle, Meisel is said to be enigmatic and secretive, appearing in public under the defensive line of a hat, scarf, dark glasses, and long black hair, from which only a hint of makeup or a crafted eyebrow escapes. The look evokes associations as numerous as the women who have posed for his camera. Like Manuel Puig’s storyteller in Kiss of the Spider Woman, there is little doubt that Meisel understands the lives, the umbra, penumbra, and scintillating facets of legendary women in a way that very few men can touch. In a 1999 interview with photography critic Vince Aletti, Madonna called her dear friend a diva (just like her), recognizing Meisel’s communion with women of magnetism and beauty — a mutual reinforcement that has proven itself over time.

Early in his career Steven Meisel did not photograph women for a living; he drew them at Women’s Wear Daily where he sat next to veteran fashion illustrator Kenneth Paul Block. In the ’70s the fashion trade journal still used illustrations on its cover, as certain department stores did for advertising, like Lord & Taylor. Meisel remembers his office companion fondly, who regaled him with firsthand stories of Jackie Onassis and the real Coco Chanel. Meisel enjoyed the regularity and security of his desk job and he relished his task, also teaching two nights a week at Parsons where he had studied illustration. But something else was calling, which had announced itself before. As a teenager he had spotted Saint Laurent-muse Loulou de la Falaise, and cover model Marisa Berenson living across the street from his high school stomping ground. For them, he had taken out a camera. In fact he even made a habit of staking out the modeling agencies for a brief chance at capturing those wonderful women, like a “paparazzi” Meisel has said. During our conversations, Meisel confided that unlike many of his peers today he doesn’t constantly carry a camera. “When I think about it, am I really a fashion photographer?” The answer to that seems easy enough, unless of course you are Steven Meisel. In truth, the answer Meisel points to in his work starts sometime around 1979 when the world began to see his future and its fuller, more complex, and provocative figure.

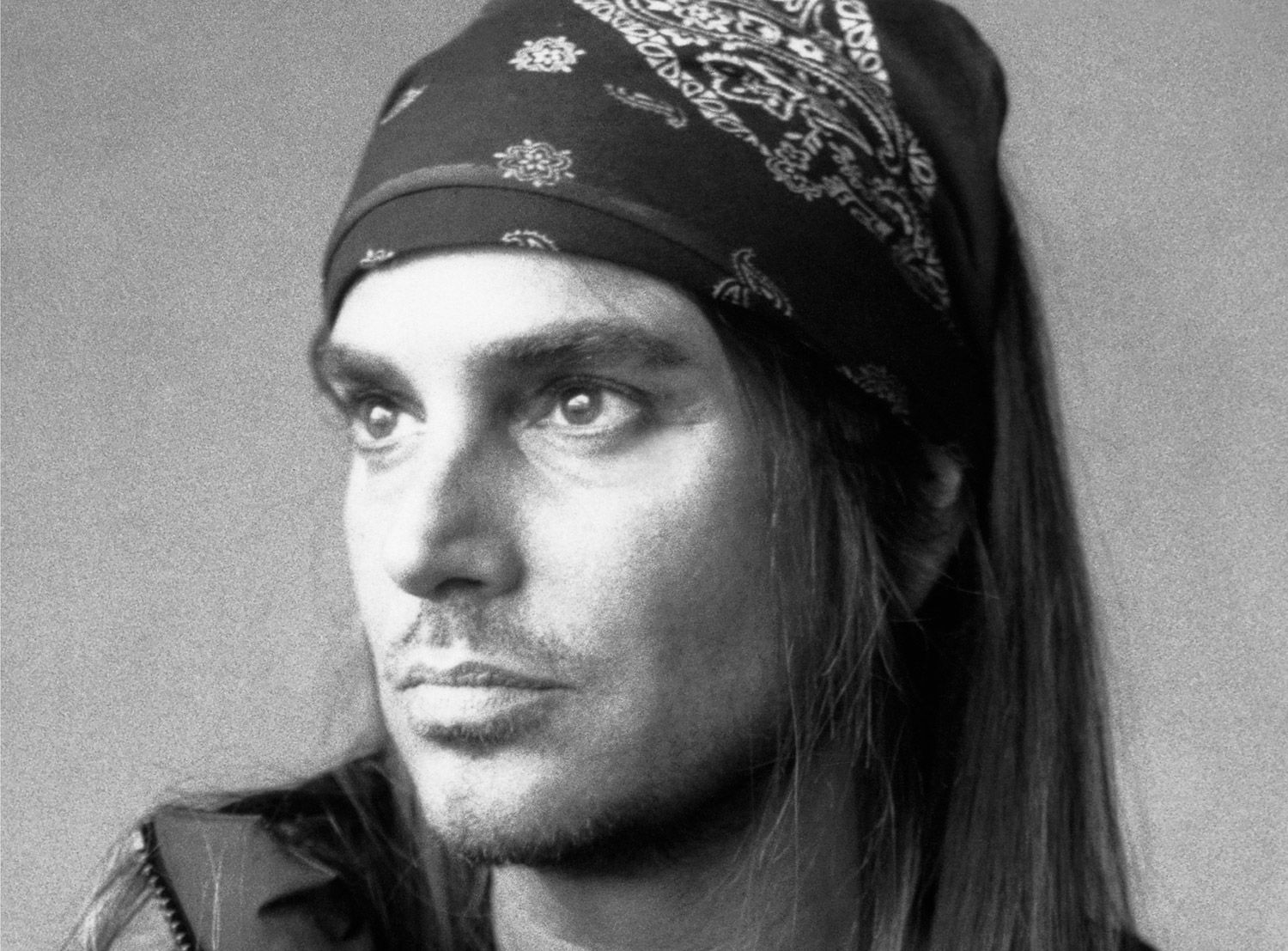

In September of that year Meisel appeared on Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party, a new wave variety show airing on a New York public-access channel. On TV Meisel was dressed in black with the bandana and rocker hair that would become his trademark. Anna Sui also remembers a leather jacket with silver studs and motorcycle boots in those days, an overall look that is still her “favorite thing for men.” On the day of Meisel’s cameo, Glenn O’Brien chants, “Why give up?” with a portrait of Lenin to his side that has been mischievously retouched; and continues, “There are plenty of things anybody can do to make themselves look better. And believe me, if you think that’s some sort of effete attitude, you’re wrong. Because it’s the beginning of social action.” The audience then greets the show’s beauty expert (Steven Meisel) who will perform a miraculous makeover for a woman named Sherrie Morales. By the end of the episode Meisel has transformed a sullen looking hillbilly into a clownish rendition of International Velvet (Warhol’s Susan Bottomly), complete with a sultry fur stole and big hair, though her painted face also suggested a send-up of a Vreeland cover girl. What’s more is that Sherrie’s country twang, which sounded completely fake, is gone. Meisel has pulled off a grand camp finale, where a mere change of wardrobe has triggered a change in personality. It is a comic outcome that gratifies a familiar but no less serious desire at the heart of fashion: self-realization the easy way, through style. The effect is not only pleasantly mesmerizing, but it is also disturbingly laughable. No surprise then that Madonna has said, “Steven, like me, likes to fuck with people.”

Much of Meisel’s most recent work fucks with fashion and its superstitions, wish fulfillment, self-loathing, and bittersweet fancies. In this work, Meisel is a pictorial satirist, breathing the spirit of William Hogarth, albeit fringed with today’s particular brand of elegance. When his images are allowed to speak, they do so with earnest conviction, as I discovered when I asked him about the recent Vogue Italia issue dedicated to black beauty, in which the spectacular editorials were entirely his:

STEVEN MEISEL: Obviously, I feel that fashion is totally racist. The one thing that taking pictures allows you to do is occasionally make a larger statement. After seeing all the shows though I feel it was totally ineffective. I was curious, because it received a lot of publicity, whether it would have any effect on New York, London, Paris, or Milan; and I found that it did not. They still only had one token black girl, maybe two. It’s the same as it always was and that’s the sad thing for me.

PIERRE ALEXANDRE DE LOOZ: Is the industry locked in its tracks?

Someday it might change. But, the designers who in the end choose the models are simply not interested in change.

Yves Saint Laurent was a pioneer for casting black models and it’s as if his death marks a narrowing perspective.

Fashion was much more open in the ’70s, and even in the ’80s, which is insane. Today, it’s totally closed down and worse than it has ever been. Look at your ads and you don’t see any black girls, maybe once in a blue moon. Look at editorials; once in a while they allow it. And on the runways they just replace one with another. That’s all I saw in all of the cities. It is very disheartening.

Speaking of an inspirational past, it seems you wanted to re-write the history of fashion photography with the “Black Beauty” issue. It’s as if you asked, “What would it look like if Horst, Avedon, or Scavullo had shot these black models?

First, the whole issue was shot in only three days – that’s the other thing that people don’t understand. Three days is long in terms of editorials. American Vogue is a day or two. Three is considered way over budget. I had to work very quickly. Some of the shoots were just a day, double shoots on top of it all. I shot the issue in LA where I’ve been for a while, because it’s a movie town that offers a lot of locations New York doesn’t. There is always a little bit of a story in my head as I am doing it. For “There’s Only One Naomi” I looked at different houses, chose one and was happy it worked out. I did the cover of her that same day, on the porch.

Did you have a big team of people?

I have too many people, tons. I can’t be on every single detail. I hire people to do this and that. They wind up having assistants; and it’s an assistant to an assistant who gets me coffee. But meanwhile I am up in some hill someplace and I still can’t get a cup of coffee. I don’t know what half of them do. There is a certain core team though – the stylist, the photographer, the model, the hair and makeup, the first assistant – who really do the hard, hard work.

And of course there are the magazine editors. You’ve been working with Vogue Italia since 1988 and it really bears your stamp. Why has it been such a fruitful relationship?

In terms of the Vogues that I work for, certainly Vogue Italia is the most lenient and allows me to do more or less what I feel like doing. Not that they don’t also kill things, but that doesn’t happen often; it’s been the most creative outlet that I have. I tend to think Italy is very conservative, which is weird, I know. Franca Sozzani, the editor, gives me room and is extremely supportive. We worked together before Vogue Italia, when she wasn’t yet the editor, on another magazine called Lei. And then there was the men’s version, Per Lui. She really likes what I do and I am grateful.

Which have been your favorite editorials?

My favorites are the ones that allow me to say something: the black issue; the poking fun at celebrities one; the paparazzi thing; the mental institution one; the ones that I have a minute to think about; all the ones that are the most controversial in fact. But it’s not because they are controversial that I like them, but because they say a little more than just a beautiful woman in a beautiful dress. I love that too, but to try and say something is also my goal.

I am a big fan of the plastic surgery story “Total Makeover,” which is like a Jacqueline Susann novel. It’s so long.

I really like that one too. That one took three days, or even less. I just get excited and go fast, and before I know it it’s so many pages!

Franca had to defend the story by saying that the magazine wasn’t condoning anything. Did you think the story would have had any effect?

If you mean on people getting plastic surgery, no. I didn’t even know Franca had to answer questions about it. It’s not like I talk to her every day. I do my jobs and I send them in and I either hear if they’re running or not, and how many pages they allowed it, and then I am on to the next one. I don’t really read blogs or things about me or my work. I am not aware of what goes on around my work, if Franca gets grief or not.

What do you say to critics that accuse you of glamorizing issues like the war in Iraq or terrorism?

I hate war. I wasn’t trying to glamorize it. I hate violence. I hate violence against women. I am trying to make a statement against it and yet everybody then says that I am for it? Basically, if you put something in people’s faces they might see it, which in this case means “DON’T DO THIS! STOP THIS!” Everybody interprets these things in their own way, but it’s not my intended meaning. I am simply holding up a mirror.

Some of your stories have crossed the line, like “State of Emergency” in 2006.

I did get flack from that campaign. The magazine refused five or six images, but I am used to that by now. After you’ve been doing this for so long, after being investigated by the FBI, what else can’t you handle?

If it’s a full blown investigation or just a furtive glance, Meisel gets your attention – which is likely why Valentino, Versace, Dolce & Gabbana, Prada, and Calvin Klein have entrusted him with repeated campaigns over the years. Meisel lives up to Diana Vreeland’s (editor in chief American Vogue 1963–1971) little jingle “We are in show business” more than most. His 1995 campaign for Calvin Klein Jeans riffed on porn screen-tests and prompted a federal investigation into the age of the models. Cathy Horyn of The New York Times suggests Meisel has had carte blanche since his bombshell collaboration with Madonna for the 1992 book Sex, which Meisel emphatically dismisses. Nevertheless, fashion is now a massive global machine to which Meisel happens to hold a velvet-lined ignition key.

“Fashion was much more open in the ’70s, and even in the ’80s, which is insane. Today, it’s totally closed down and worse than it has ever been.”

Anna Sui explains without a drop of hesitation: “Steven sets the stage for everybody else. Everybody waits for what he does.” And luckily Meisel has visited Sui at her studio for years to comment on collections. “There are so many things about Steven that make him important to the fashion world. What you see in Vogue Italia will be on the catwalks two months later – that’s how inspiring he is,” Linda Evangelista tells me from a Paris hotel on the tailend of a shoot. Meisel’s pictures, Evangelista implies, turn around and shape the clothes they are supposed to document, making Susan Sontag’s epithet for our image-obsessed society – “fashion is fashion photography” – ring even truer. Art Director Fabien Baron who worked with Meisel on Sex explains that early in Meisel’s career “he could not only talk about style, hair, makeup, and art direction, he could do it all himself and you knew that he could do it better than anyone else.” While some high-powered analysts have told me they feel Meisel’s blue-chip stock seems ever-so-slightly marginalized nowadays, during the decade reign of the supermodels you might have said Steven Meisel was fashion. At that time a memorable club of models had mobilized a kind of market monopoly, dominating media platforms from runway to print. Beyond the magazine pages they made cohesiveness a professional asset, publicizing themselves in unison over a far-flung social scene with Meisel on their arm, their “constant escort” as Bob Colacello has written. Naomi Campbell confided that Meisel allowed her to be a teenager when they worked together in New York, pairing business with nights out dancing, vintage shopping, and trips to Coney Island. For Valentino’s 30th Anniversary Gala in Rome, Linda Evangelista was accompanied by Meisel, who improvised her wardrobe and makeup on the spot, at the window in their hotel room. The pink gown and red coiffure confection Meisel created for Evangelista on that night in 1991 proved very popular with the press, she recounts, despite the horde of other celebrities and 1,600 guests swarming the three-day event. From Meisel’s pictures of these sirens, one can see not only a professional eye, but a gaze that has studied its cherished subjects from every angle and in all sorts of real situations, from cold-coffee breakfasts to champagne-doused nightcaps. Naturally, I had to ask what it was all about:

STEVEN MEISEL: I was photographing the girls that I loved. I liked glamour and these girls were very glamorous. The fashion was very excessive. The period was very excessive. It wasn’t something I did consciously: we would go on vacation, go to dinner, hang out, and talk on the phone. We were friends; it was my beginning as it was theirs.

So what we call the supermodel moment is really your personal history written large?

It kind of is. We were having a great time and documenting it. We used to go to the shows in New York and Paris and they were much larger events, or maybe it was new to me and more exciting. In Paris, we had adjoining rooms. It was always Christy, Linda, and Naomi. We were having fun all around the Ritz. We played and had a great time, and I still do when I see them. Now I go to work and it’s a different world. I’m different and the models are different. What am I going to say to some sixteen-year-old girl who doesn’t speak the same language?

But you came to fashion at an early age, didn’t you?

Yes! I was a stupid, fashion asshole! I loved the magazines and I just connected immediately at a very young age, probably in the fourth grade. I loved it. Later, in the sixth or seventh grade I used to take a camera, an instamatic perhaps, and snap models on the street. I still have those. I blew them up and they’re actually good, great even. When I was a kid the models you saw in the streets of New York were out of another world – people would stare. They looked the way they look in magazines, right out of Vogue, on the street! They were superwomen. They were unbelievable. Now its jeans and t-shirts and stuff like that. It was a different period. They did their own hair and their own makeup. You had to be very creative. They went to jobs done. That’s the way they were.

What captivated you most?

I don’t know what it was. Beauty. I just reacted to it. It was beautiful like a painting. I can’t say why. I can still clearly imagine some of the women in my head, girls at the time. It was just beautiful. It was just beauty to me.

Meisel says this with the heartfelt sincerity that would stop any aesthete dead in their tracks. When he speaks the word “beauty” it hovers like a space-age hologram of classical archetypes, a metaphysical ideal landing like a red carnation tossed down from the ether. And that’s how extraordinary the view from Meisel’s lens must be. Anna Sui asserts, “He can make any model look better than she ever did.” She remembers her first professional phone call from her friend for a Valentino shoot: “‘Bring your suitcase and let’s do what we always do’ he told me,” and since then she has often styled for Meisel watching him cajole models, a ritual she says is “magical, like falling in love.”

Meisel’s way with models leaves a lasting impression, and not just on the printed page, as if there were a formative Meisel technique. Indeed, he coaches models in posture, expression, and attitude. Linda Evangelista says, “With Steven you don’t feel alone when you are on set. So many photographers can be insecure, they don’t know what they want and you don’t know if you are pleasing them. It’s not like that with Steven. He is confident and makes you feel safe. The atmosphere on set is light. If he says what you are doing is good, then it is because he has the most impeccable taste and judgment, like when he makes a call on color, lighting, or placement.” Naomi Campbell says that the atmosphere on the set is “always controlled and concentrated, even when loud music is playing.” Meisel, she says, is a true artist. “He makes you feel beautiful, like a chameleon, like I can take on any character imaginable. He taught me how to be a blank canvas.”

“Not since Avedon has someone had such a level of consistency and inventiveness.”

Here Campbell identifies Meisel’s use of role-playing, a key device in much of his work including Sex which involved late-night discussions with Madonna on the topic at New York’s now defunct male burlesque theater the Gaiety.

A chameleon himself, a promiscuous image sampler, critics object that Meisel is not one for original ideas. Vince Aletti, who co-curated Meisel’s only gallery show to date at the White Cube in London, argues that his shape-shifting ability is powerful: “Not since Avedon has someone had such a level of consistency and inventiveness.” Aletti takes Meisel’s “voracious” use of source material as a badge of distinction: “Other photographers are insular, but Steven reflects the world at large.” Meisel matches his panoramic insights with an encyclopedic output; a body of work that Fabien Baron asserts, “has defined what modern fashion photography is all about.” When I put the question of influence to Meisel he answered with deadpan simplicity, the way Georgia O’Keefe talked about the inspirations in her paintings: they are what they are. Deborah Turbeville? Guy Bourdin?

STEVEN MEISEL: I think it’s like everything that you grow up with becomes part of your aesthetic eye. It’s not that I am consciously thinking about any of it. I guess it becomes part of who you are.

In 2004 you were included in a MoMA show. What did you think of it?

I never went to the exhibit because I didn’t want to be a part of it. Firstly, I don’t like group shows and when I read what the theme was I didn’t like it. I didn’t agree with what the person was saying in her proposal letter. But my agent said I should do it – we never agree. I said, “If it’s so important, you talk to them, but I don’t want to have anything to do with it.” The curator chose the pictures and they were not pictures of mine that I liked. So for me the whole thing was something I wish I had listened to my heart and my instincts on. There really was no point for me to do it. And I didn’t want to read reviews and people discussing whatever, pontificating about nothing.

What did you think of Cindy Sherman’s pictures in that show shot for Comme des Garçons?

Again I didn’t see the show, so I can’t comment. But I think Cindy Sherman is incredible. She is another brilliant artist.

They are really grotesque.

A lot of her pictures are. She has a sick sense of humor so I would think they would be sick. But that’s great, that’s her point.

Is that a problem for fashion?

Yes. You don’t see her pictures in fashion magazines. She is not a working commercial fashion photographer. She is an artist that uses fashion in her images. I find her pictures very fashion-oriented, starting with the movie stills. However, her pictures would definitely be a problem for a fashion advertiser.

So let’s talk about glamour. I don’t understand it anymore. What is it?

That’s a hard word too. I hate to sound old-fashioned, but I don’t find many actresses or movie stars glamorous anymore. I don’t find award shows glamorous. I don’t find any of this TV stuff with fashion commentary glamorous. I don’t find anything glamorous today. I think it may be something of the past.

I am still wondering if you try to define it. Is it the same thing as being beautiful?

The Duchess of Windsor was hardly a beauty, but she had incredible glamour, as well as Diana Vreeland. I don’t think beauty has anything to do with it.

Do you have to be famous?

No. I‘m sure you have women friends who you think have something special but aren‘t necessarily in the public eye.

Is it magnetism?

I think it’s some sort of charisma. It’s hard to explain. There were women that, while growing up, I found glamorous. But I never met or knew them. Could their magnetism come out through a photograph? I never knew Babe Paley, but I thought she was a glamorous woman.

Not knowing somebody intimately might make them more glamorous.

Well yes. That we know by now. It’s better not to meet your idols because in the end everybody is just human.

How do you feel about photographing friends?

I dread it. It’s just too personal. It’s my own fear of failure – like I might fail the person or can’t live up to the expectations of what I really feel about them, my love or whatever it might be. With the girls that I know like Linda we can disassociate our personal feelings. But for me to take a portrait of my parents is just impossible!

Anna Sui explains without a drop of hesitation: “Steven sets the stage for everybody else. Everybody waits for what he does.”

Is there any glamorous imagery left in fashion today?

There is still a stylization and an idealization of women, but it’s taken from the past. It is taken from the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, old Hollywood, the ’70s, the Helmut Woman, the Guy Bourdin Woman. I’ve seen it all before!

Do you think Prada understands that?

They have a different sense of glamour. It’s more modern and relies less on clichés like false eyelashes and lipstick and things that people think are obviously glamorous, like Marilyn Monroe. I like that too, but theirs is more intellectual.

Speaking of lipstick, what was “A Sexual Revolution,” which you shot for W, about? It was like Fight Club in women’s lingerie.

I find that men are subject to the same idealization that women have always borne. It isn’t exactly a feminization of men. Men have never really been considered sex objects. Yes, maybe someone would have said that a man was handsome, but it wasn’t that he was made to be like women, always objectified and always nude, showing cleavage. With “A Sexual Revolution,” I was saying that we have finally done it to the men. And I tried to pick men that were a little bit more androgynous. So it wasn’t the typical hunky thing that people today consider the only way that a man has to look, just like a woman has to have breast implants, and a certain breast and waist size. Society has finally come full circle and does the same thing with the men. I don’t think this is a positive step forward in how we feel about ourselves.

So what’s your perspective on gender? If you could eliminate it from society, would you do it?

No. I would eliminate differences in social equality of course, but you can’t change nature. I watch it in my dogs – my female dog is definitely a girl and my male dog is definitely a guy. It’s the same thing with my cats.

Madonna definitely made men into a sex object.

We did that together.

Well, what else did Sex do for culture?

It allowed people to not be so afraid of sex, or if anything to simply talk about it. It’s part of life too, although not necessarily the scenarios we illustrated. I think it helped people to not be so repressed.

Do you feel that now you could have pushed that book farther than you did?

Yes, absolutely, meaning her original idea did work; it did open people’s eyes. Now you can go further. But I don’t even know what that means. Mapplethorpe did all those sex pictures. I don’t know what further could be. I am talking just in terms of commercial photography, what one is allowed to see in advertising and commercial magazines.

I’ve noticed you don’t photograph nudes so often. Even in Madonna’s book, clothing is critical in every picture.

Because I am a fashion photographer and the job that I do is with clothing. I work everyday. I started out being a commercial photographer working for the magazines and advertisers, so I never really had time to try nudes. It doesn’t come up. I would like to I guess, but on the weekends it’s not like I want to take more pictures! Herb Ritts, who was a good friend, always managed to have his nude guys. If you want it enough you push it in there. But it wasn’t as important to me. A lot of people get off on stuff, but it’s not what I am really about.

So fashion photography doesn’t have to be kinky to sell?

I think some of the most successful fashion pictures were just of beautiful clothes. I think that we have gone further and pushed it to kinky because clothes are such shit now. I shouldn’t say that but it’s not like when Irving Penn did a picture of an original Balenciaga where the dress was like architecture. We’ve become a world of H&M. If you are really selling T-shirts and jeans you have to be eye-catching because there are so many images out there. You are inundated all the time, whether it’s on TV or the Internet, buses, bus stops, taxis, or billboards. I guess the only way to get people’s attention is by trying to do something outrageous, but I don’t think it needs to be kinky to be good.

Did you expect the Calvin Klein campaign to blow up the way it did?

Not at all. It was the period of grunge and I was working in a very isolated world of fashion, fashion photography, and models; to me, that’s what was going on! I didn’t think much further into the world.

Was the FBI totally intrusive?

Yes. I had the whole thing. I think Clinton even mentioned the scandal.

At the time he was going after that and “heroin chic.”

Right, and it’s all so sick anyway. He’s getting blowjobs from someone in the office! No one was shooting dope on the set; no one was fucking anybody or doing anything sex related. It’s middle America; it’s the world. It’s a sick place out there. So no, I didn’t expect anything.

How much do you obsess over choosing the right location and dressing the set?

I go as far as I can, until there is no more I can do, until I’ve spent the time, gone through all the location pictures, until it’s too expensive and the client doesn’t want to pay, or the place becomes unavailable, or you can’t get the set decorator that you want.

Are you really concerned with every detail, the glass, and the silverware?

There is nothing I leave out. I just can’t.

Do you storyboard sometimes?

No, I have it in my head. It doesn’t work for me to storyboard things. I remember when I first met Mr. Liberman at Vogue, he used to storyboard and draw stories out. When we would have a meeting he would say we need a big hill here and this here and I tried – but it’s not the way I do it. I understand Guy Bourdin used to do that. I usually have in my mind what everything is, which can be also very difficult. You have to explain it to many people many times, and still when I get there it’s usually not the way I want it. I am asking people to interpret and it’s not easy. They don’t have the same eye as me.

Sometimes that interpretation actually helps, because they’ll see it in a fresh way.

Very rarely.

Do you interior decorate your homes?

Oh yes, and that becomes problematic. I am not easy, but the people that I work with are insane as well! The guy I work with in New York is Peter Marino. We get along really well. I push him and he pushes me. I am very into what I am looking at visually, my room, my furniture, a fabric, a house, the architecture, decorating all of it.

Do you keep any of your photographs around?

I never did, not until this year.

What made the difference?

Firstly, Peter thought we should hang pictures up on certain walls. He asked if I had any framed pictures but I don’t do that. I don’t like to look at them because all I see are the things I didn’t get right. So, it’s difficult. Secondly, I never had pictures of people that I knew although I had tons of pictures of every body. But recently, I remembered somebody telling me that their therapist told them that it’s important to have pictures of people that you know as well as pictures of yourself around.

What’s the reason?

I guess to accept yourself in the end; to own yourself and to own those people that you love. So I thought it was crazy that I wasn’t hanging pictures at home. Still when I walk past them it’s hard. A lot of pictures are from the past and that always brings up melancholy and that’s not fun. I should look at it as a good thing, like its great that I knew this person or that person and so what if this one looks old now. There is the vanity issue there too. And people will come over and say, “Gosh, look at how young so-and-so looks.” [growls]

Would you ever pose for a photograph yourself?

I did once with Annie Leibovitz for the GAP. I think it’s in the GAP book, which I don’t have.

What does it feel like to be on the other side of the camera?

I hate it.

How about the movie camera?

Even worse, I despise someone filming me. A picture at least is frozen. But with film, you have to listen to your voice and you see your gestures. I am way too critical. I hate it.

But weren’t you in that 1983 fashion flick Portfolio?

Yes. A friend convinced me to do it. But what’s shown in the movie isn’t how I work and isn’t what I do. They’d say, “Scream and smoke the cigarette, and make crazy eyes with Kim,” or whoever. And then: “Finish, and jump up screaming.” Like an asshole I did it. It was better than doing a sex tape I guess. I was young and stupid, but if that‘s the worst of it, then fine.

Well, your work is strikingly cinematic. Could you see yourself as a filmmaker?

I don’t know if I could deal with the whole business out here in LA I go back and forth from here to New York, but I don’t feel part of either community. I do love movies though.

Are there any you recommend?

I watch 8 1/2 a lot. I could watch anything by Fellini a million times! But, I can’t deal with Satyricon or Roma any more. I love all the European movies. I like Antonioni. I can always watch Blow-Up because of course that was an inspiration, but not as much as I used to.

How about Breathless?

I am not in love.

Or one of my favorites, Paris Is Burning?

Yes. In fact I photographed Dorian, the older star and once judged a ball – they almost killed me. If they don‘t get a high mark, they hit you with the scoring card – I learned quickly.

Was it about ugliness?

I didn’t find it ugly, what do you mean?

Those girls were not supermodels and their lives were not exactly beautiful.

I guess on a deeper level I found it sad. First of all they were men so they lived in a world of fantasy, hated by the rest of the world. At the very least, I think, they created a world of their own and were able to have some fun – society is cruel.

Credits

- Interview: PIERRE ALEXANDRE DE LOOZ