ALESSANDRO SIMONETTI Captures Italy’s UNDERGROUND SPEED FANATICS

The speedway runs anti-clockwise. Its riders lap it in a tightly-wound circle. The closer they are to the inner edge, the faster they go. This type of racing is characterized by motorcycles that have no brakes and only one gear. It encourages a kind of fluid depravity, one that resembles riding an animal more than a machine. It is therefore ironic that speedway began in Italy with British soldiers modifying their street bikes for abandoned horse tracks in Udine and Trieste.

Since then, the Santa Marina Stadium in Lonigo has become the center of the Italian speedway, producing champions for a deadly sport that rarely makes it past a local audience. Their crowds are often small and the riders’ jerseys are emblazoned with small-business logos. This is the world documented by photographer Alessandro Simonetti during his time photographing the speedway racers of Northern Italy.

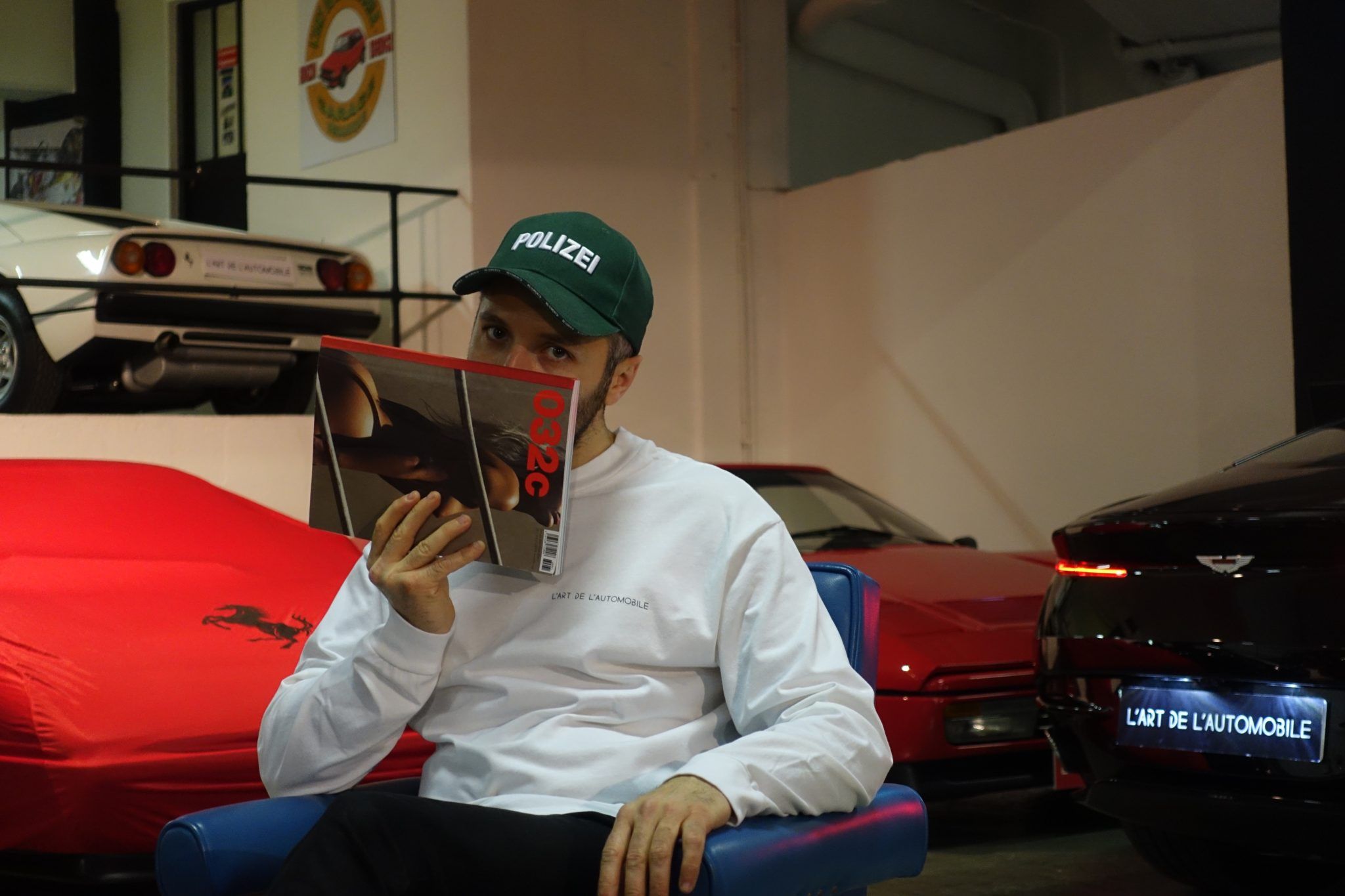

Following our obsession with speed and the freedom-body that led to our Motocross Collection, 032c spoke with Alessandro Simonetti:

What type of racing are you showing in these images?

The work portrays a really singular practice of motorbikes. It’s at the bottom of the motorbike pyramid – the least accessible and definitely the kind that has lost the most hype from sponsorships and crowds. The races take place on anti-clockwise dirt oval tracks and the riders slide their bikes sideways, reaching up to 110 km/h. The origin of this practice is lost in the dust, but the first appearance of speedbikes happened even before the First World War in the US and eventually gained traction in Australia in the 1910s and 20s.

So there are rules to the unruliness?

The FIM [Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme] regulations state that the motorcycles must have no brakes, be powered by pure methanol, use only one gear, and weigh a minimum of 77 kg.

What is the connection between Italy and speedway?

Speedway arrived in Italy after the Second World War and found a perfect playground on the abandoned horse-racing tracks of Udine and Trieste in the northeast of Italy. UK soldiers were using street bikes adjusted to fit the track and they were actually responsible for building the hype for a practice that was never before seen in Italy. The Lonigo horse tracks were eventually blessed by the Italian “King of Speed” Dario Basso, who tested the track with his Gilera and declared it practicable for official competitions – this was before several riders got injured and died. Lonigo decided on a proper stadium to be able to host the increasing number of riders, eventually giving birth to local champs like Paolo Noro, Valentino Furlanetto, and Giorgio Zaramella.

Do you ride these bikes yourself?

I never owned a proper motorbike. I had various scooters during my youth: a Booster, Rapido Peugeot, Garelli, and a Vespa. I never owned a car either, but because of the skateboard and snowboard scene, which I was documenting from a young age, I had the chance to follow the early career of one of the most influential FMX riders in Italy, Alvaro dal Farra. I met him at the Academy of Fine Arts in the late 90s while we were both students and witnessed his shift from dirt jumps and basic tricks to metal ramps and backflips. That was the peak of my relationship with motorbikes – it’s just an aesthetic-platonic crash! I grew up with two women and there was no MotoGP or Formula One running on our TV, so it was a random encounter which revealed my infatuation toward this subject.

I always think of Italy being famous for fancy red sports cars. How is Motocross considered culturally by Italians?

Italy has a long tradition and passion for cars and motorbikes. Motocross, especially in the northeast where I come from, is pretty popular. You easily see five-year-old kids rocking the tracks.

Could you expand on some of the behind-the-scenes stories from when you took these pictures?

I spent some time with a few riders while they were preparing the bikes, and according to one of them, speedway is the most dangerous of all the bike sports. It’s a big statement. If you ask me, I would say FMX is the most dangerous, but what the rider said revealed a strong passion and sense of pride for this sport that suffers from a total lack of attention.

How so?

All the riders compete independently. The sponsors that were embroidered on their leather suits were all local companies, such as the bank, the butcher, or small-business owners. I think what captured me at first was the style of the speedway posters that I saw when I was little: duotone, black and yellow guerrilla wheat paste on suburban walls.

What keeps you coming back to these bikes and their riders?

The shape of the bikes, the absolute absence of high-end technology, the moves and attitude on the track – they perfectly fit my aesthetic in photography. I shot the whole competition on film with an old Nikon set, pushing the ISO beyond and not caring about having a rough result in terms of contrasts and grain.

Do you think there is a political aspect tied to motorbike sports?

Speed is political to me. For instance, think about the Futurism movement of the early twentieth century that emphasized speed, technology, youth, and provocation, as well as objects like cars and motorbikes. Conceiving of speed as a tool to move faster, in order to leave behind the weight of the Italian past. I also see a thin religious vein in the sport. I’m not referring to the faith you might need to push yourself to that level of racing – it’s more a simmering anti-religious attitude of putting your life at risk against the will of god.