THOMAS BERNHARD: Possessions

|Charlie Fox

“I’m not a country person at all, fundamentally. Nature doesn’t interest me whatsoever, neither the plants nor the birds, because I can’t tell them apart and still don’t know what a blackbird looks like. But I do know that I cannot live in the city in the long run, with my bronchitis. I don’t leave the farm at all anymore, even in winter, because I half kill myself when I’m in town.” In 032c Issue #36, we explored the interior life of Austrian author Thomas Bernhard (1931–89) – through the interiors of his homes, and the objects that populated them. Below, an excerpt from the monograph devoted to the topic, Thomas Bernhard: Hab und Gut (Vienna: Brandstätter Verlag, 2019), translated from André Heller’s introduction, and an original essay by London writer Charlie Fox, attempting to process – or inhabit – the order and madness of Bernhard’s material world.

When did Austerity become so much fun? Who could have predicted that a tubercular, acerbic mansplainer whose never-ending sentences seemed exclusively suited to the rollercoaster grammar of his native tongue would become the most influential German-language author of the post-war period? Like an irate blogger tapping out a venomous account of the world’s shortcomings, Thomas Bernhard’s self-hating nihilists speak with an enviable freedom: little concern for their listeners, and even less concern for themselves.

In Gargoyles (1967), the insomniac aristocrat Prince Saurau chews through the final 100 pages of the book, his monologue displacing the characters and scenes that came before him, lamenting the slow corruption of the Austrian countryside. In Woodcutters (1984), a dinner guest is poised with a glass of fizz, seated at the low end of the table in a wing-backed chair, sounding off on the hypocrisy, stupidity, and ignorance of the Viennese cultural elite. “The forest, the virgin forest, the life of a woodcutter,” he smirks. “That has always been my ideal.”

In his early life, Thomas Bernhard worked as a grocery clerk, an actor, and a crime reporter – professions he hated, perhaps because he saw the cynical, nepotistic, and arrogant succeeding all around him. As a writer he made a monument of his ability to criticize, eviscerating the farce, triviality, and pomposity he saw everywhere in society, in the Catholic state, in bourgeois culture. Somehow Bernhard’s brand of truth-telling feels more shocking today than it ever has, 30 years after the writer’s death, when everyone sees everything but nobody pays attention.

A teutonic Samuel Beckett for whom failure, death, and suicide were a source of animation, Bernhard’s successes were undeniable. He received numerous prizes, always in performative call and response with the various committees that bequeathed them. Upon accepting the Austrian National Award in 1968, he condescended to deliver a speech that began: “Esteemed Mr. Minister, esteemed assembly, there is nothing to praise, nothing to condemn, nothing to accuse, but a great many things are ludicrous; and everything is ludicrous when one thinks about death.” The dignitaries in the theater led out, but self-immolation is a Viennese tradition, an engine room for rhetorical showmanship established by Bernhard’s forebears Stefan Zweig and Karl Kraus. State money was always useful, practically, and Bernhard knew exactly what to do with his Austrian cash prize: “It had always been my wish to have a house to myself, and even if not a proper house, at least walls around me in which I can do what I want, permit what I want, lock myself in if I want.”

Shortly before his death – reportedly, by assisted suicide – Bernhard plotted his final emigration, insisting that his works never be republished or performed within Austria. They were, eventually, but he slipped across the border all the same. Bernhard’s furious, propulsive, and ultimately profound style lingers in the bad breath of the dons of the literary Anglosphere. He may have despised his austere, rocky Austrian landscape, but he cherished the buildings he renovated at Ohlsdorf-Obernathal 2, revisited in Thomas Bernhard: Hab & Gut, a 2019 interiors monograph from Brandstätter Verlag edited by André Heller and laden with images of the author’s obsessively presented spaces and furnishings – vignettes of bespoke austerity.

There he lived the life of a solitary woodcutter among his pedantically selected objects, like his demented aristocrat Prince Saurau, who had his own prescription for filling and existing in empty rooms: “The person who dwelt in them had to fill them solely with his own fantasies, with fantastic objects, in order not to go out of his mind.” What follows is a look at the undisturbed rooms that Bernhard left behind, with a preface by Heller, and an intervention from the abovementioned Anglosphere by London essayist and curator Charlie Fox, author of the encyclopedia of horror and camp This Young Monster (2017).

I. PREFACE

by André Heller

THOMAS BERNHARD was the most massive disruption to Austria’s literary energy field in the second half of the 20th century, subject of inexhaustible fascination.

He belonged to no club, to no group, to no circle, to no persuasion, to no party, to no artistic organization whatsoever. He always belonged, to the utmost degree, to himself alone, and could thus operate with a ruthless selfishness, taking no prisoners. With his linguistic machete he cleared a path to lasting validation for his brachial truths, brilliant blasphemies, grotesque exaltations, touching attempts at love, and other eruptions of imagination. Bernhard was also a sardonic trickster, a master of the underhanded blow, a virtuoso of high-performance agitation. All in all: a solitary man of a kind one encounters only once in these unholy times.

I’ve been interested, my whole adult life, in the dwellings and houses of exceptional characters – always valuable supplements to the understanding of the individual and the oeuvre. The apparently incidental, even the anecdotal often belong to the most revelatory. (I remember for instance how deeply impressed I was 30 years ago to learn that Hugo von Hofmannsthal, in 1912, had spontaneously purchased the now legendary 1901 Picasso self-portrait Io out of the display window at Munich’s Galerie Thannhauser, and placed it in his study at Rodaun Castle, a source of inspiration and solace. This unexpected fact fundamentally changed my view of the writer behind the Chandos Letter.)

When the Fabjans – Bernhard’s half-brother and the sole and responsible heir to the Thomas Bernhard estate, and his equally passionately involved French wife Anny – so kindly made the author’s home in Ohlsdorf accessible to me, I encountered a down-to-the-smallest-detail, meticulously staged private cosmos full of illusions, red herrings, and false assertions of supreme elegance. Over all, a beguiling as if.

As if Bernhard had been landed gentry.

As if many guests had spent the night there.

As if he had cooked in the modern kitchen and eaten in the dining room.

As if he had been a huntsman, a bespoke shoe fetishist, an equestrian.

Much of this refers, for those with profound knowledge of Bernhard, to descriptions in his plays and prose. Perhaps these descriptions have been recreated, after the fact, in reality.

II. SUICIDE NOTE

by Charlie Fox

NOPE, I CAN’T DO IT. I can’t tell you about what the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard is supposed to mean to us now after being dead for three decades. The whole concept renders me into panicked jelly, it’s hellish, and I’d rather feed myself to wolves or throw myself down a flight of stairs in slo-mo forever, my head splitting in the end with a loud and ghastly crack. Nope, I can’t do it. I don’t have anything to tell you about somebody who left sentences in his wake that you read in a state of morbid fear as if they were a kid’s blood snaking through snow. I’m freaking even before I get onto my actual stimulus which is this new book, Thomas Bernhard: Hab und Gut, about his house secluded in the Austrian mountains (Bachelard blah blah blah: The Poetics of Get the Fuck Away From Me), or how the house’s ghoulish vacancy is recorded in photographs like the exposition for some bleak chamber drama. Funny Games? Even though I compulsively rewatch VHS rips of MTV Cribs on YouTube, the thought of stalking the same lonely corridors as Bernhard like an apprentice ghost makes me want to puke. I can’t even begin to sneak over the threshold like a vampire because the house and its contents make my flesh, uh, horripilate. OK, it’s wrong: Bernhard’s farmhouses remind me of enormous coffins but inside the coffin is the graveyard: all the strange, abandoned objects lined up. I think I’m going to puke. That hypersensitive teenage waif – the “problem child” – in the portrait hidden by green curtains will stalk me in my sleep. He probably sounded like an old door creaking when he sobbed, masturbated tons, smoked opium in the forest and died, aged 17 or something, by gobbling toxic mushrooms to escape a crush who didn’t even know he existed. The fear of the coffin house stops me from feasting on microscopic details such as Bernhard’s fluffy socks, monstrous lumps under the green quilt that make me think of Bernhard clumsily trying to hide a corpse, the two bodies empty at each other in the bedroom – psychotic ghosts mutilating each other in conversation. And I can’t stay long in his barn with all the straps lined up inside as if in memorial to a dead horse or to provide a bunch of frisky possibilities if he decided to hang himself. Maybe, a few weeks later, a pack of ravenous German Shepherds would stagger in from the woods and chew off his swaying, putrid boot. Maybe it’s fun (“so-called ‘fun,’” Bernhard would’ve said) to imagine him still alive and staring into the Big Nothing that is existence itself, cadaverous at 87, scoring cans of Monster energy drink with their thug-rave graphics on Amazon Pantry, or watching Ed Atkins’ Old Food videos (the knight weeping, the guttered candle) as if they were reality programming, or gawping at Leaving Neverland and thinking, “Ugh, somehow I understand this unspeakable goblin’s need for a hidden nest.” Bernhard’s pile is his Neverland. And Bernhard was a crime reporter in his youth so maybe it’s fun to imagine him binge-watching Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes on Netflix. (Think about the lurid crime scene reconstruction that kicks off his novel The Lime Works: brain matter frozen in a cosmic tableau on a chilly cellar floor.) And maybe there’s a grisly excitement in wondering what this wizened Bernhard with his ulcerated brain would’ve said about Josef Fritzl, the Austrian psychopath whose horror-show crimes were discovered in 2008. It all could’ve crawled out of Bernhard’s head. Fritzl raped and fathered multiple children with his own daughter in a special lair built under his house. Everybody thought she had run away. Certain areas of the house can be, uh, dumpsters for evil deeds. Remember Buffalo Bill in Silence of the Lambs? I wonder what Bernhard would’ve said about how, in a weird contrariwise rehearsal of his later crimes, Fritzl had earlier locked up his sick mother in the attic as she lay dying, a tyrant trapped. I’m sorry, being the puppet master for this zombie Bernhard is so much fun. Nope, I can’t do it anymore. It would be much kinder to let him rot. (Very Bernhard to note the extent of your decay.) Not that I even believe Bernhard is dead. Even after thirty years, bile remains acidic. His voice with its trademark relentless insomniac crawl is still buried alive inside the books and eager to infect the next person. Yeah, Bernhard was a misanthropic comedian whose strangely musical, looping books perform a baroque analysis of the dark thoughts inside his head (he loved Bach), and yeah, he lures you down into the void – I’m writing sentences about Dante’s Inferno here; I’m setting them on fire. His voice is so intimate it’s bacterial. He becomes your thoughts, he speaks through you. Then you feel this creepy bulimic flux between words, this ugly substance he must stuff you with as if you were the rancid black bird from Correction that Heller relentlessly packs with caustic foam, and words being something that must be puked out unstoppably. Biographical vultures will know Bernhard was stricken with tuberculosis, a bacterial infection caused by exposure to a diseased person’s breath – ugh, their grisly interior stuff – so how could he not see other people as contagious matter, sacks of flesh carrying infection? Now everybody is bacterial. They get in through your eyeballs. Nowhere to hide. Bernhard’s narrators and their horrid dream of shutting out the world (even as it melts around them!) would be more hopeless than ever today. Still, they crave isolation, which makes them very 2019, very apocalypse 🦄. And I can’t spell out the fatal paradox of feeling very isolated and yet swamped by the world in all its voracious noisiness, like it’s newfangled. That’s what plenty of the reclusive freaks in Bernhard’s works feel, too. This makes them more forlorn and more – I think I’m going to throw up – “alive,” undead, whatever, now. Suicide would still be a hot method for dealing with many of their problems. They could keep the note on Instagram.

I mean, in the end, what am I supposed to tell you? “I’m a big fan”? Ha ha ha. Nope, I can’t do it. I always thought a great title for Bernhard’s collected works would be the same thing that Kurt Cobain choose for his last album before everyone else told him it wasn’t funny but scary: I Hate Myself and Want to Die.

Credits

- Preface: André Heller

- Text: Charlie Fox

Related Content

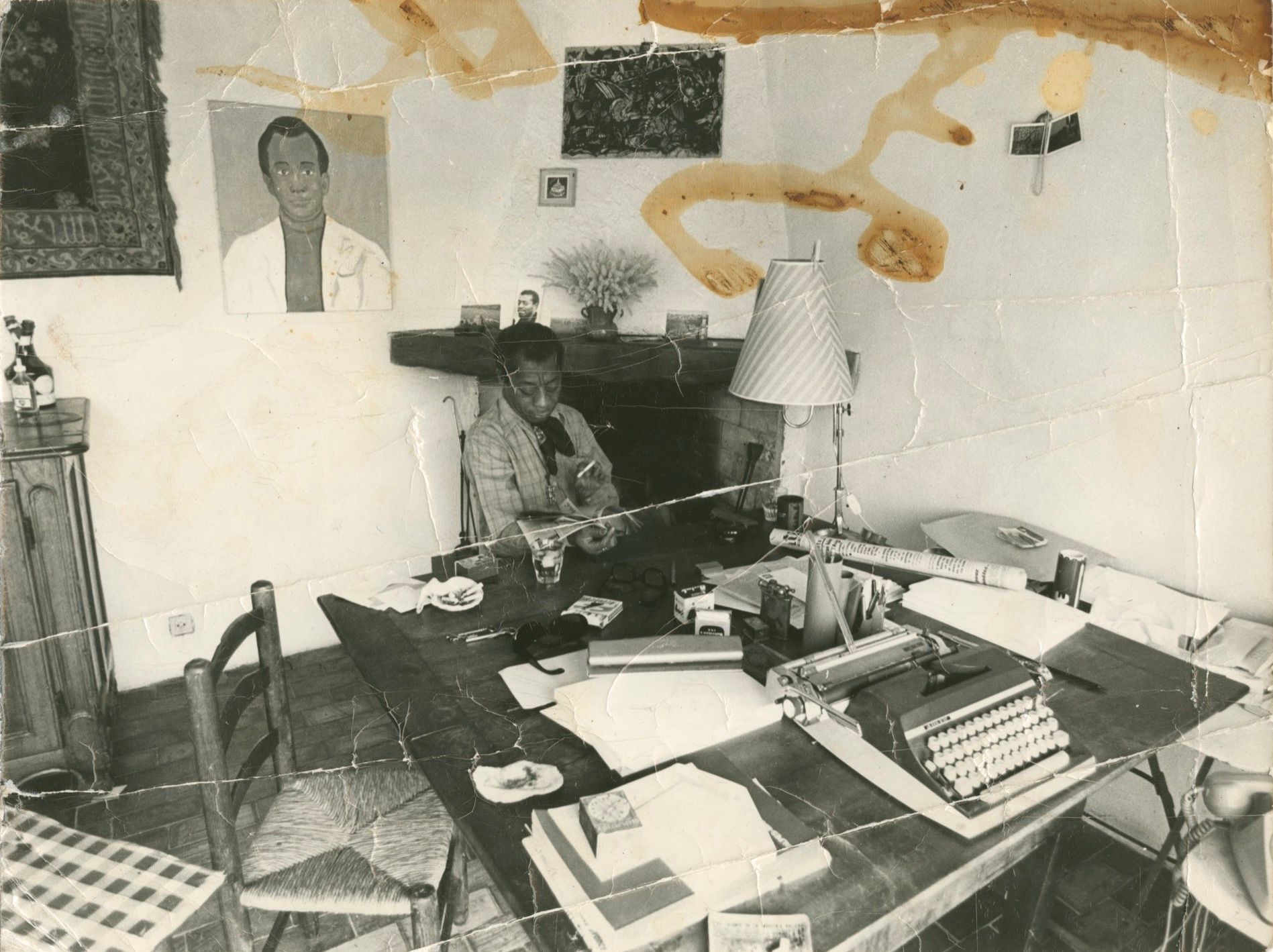

House as Archive: James Baldwin’s Provençal Home

Grüß Gott! Austria’s ARTHUR ARBESSER Is Leading Milan’s Young Design Renaissance

HELMUT LANG: The Searching Stays With You

LORD GEORGE WEIDENFELD

A Fireside Chat with KRAMPUS, the Alpine Christmas Demon

The Mutant Fantasy of DINGYUN ZHANG

JEREMY O’HARRIS: A Season in Hellbrunn