THE WOLF STANDS/CRIES ALONE

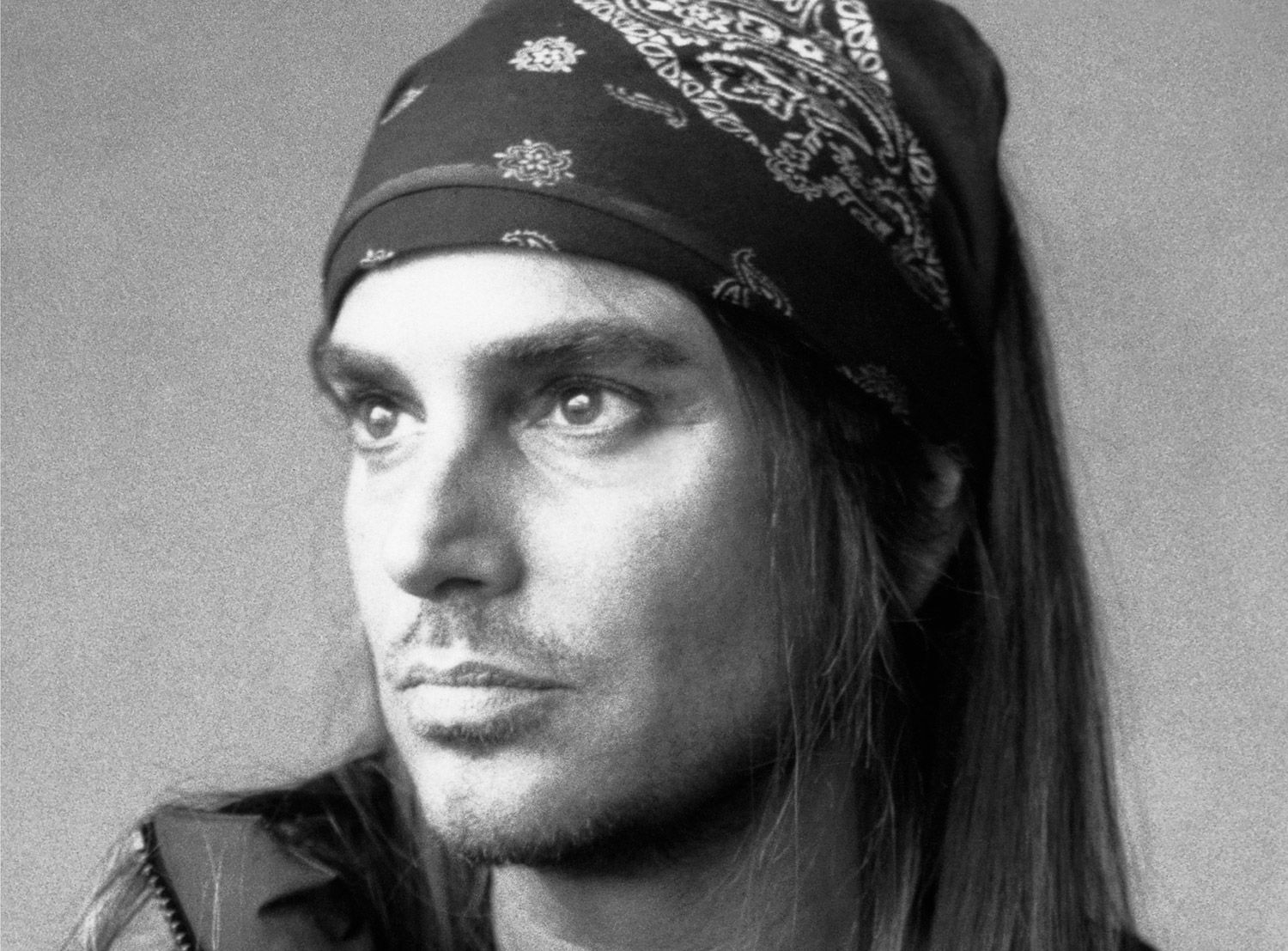

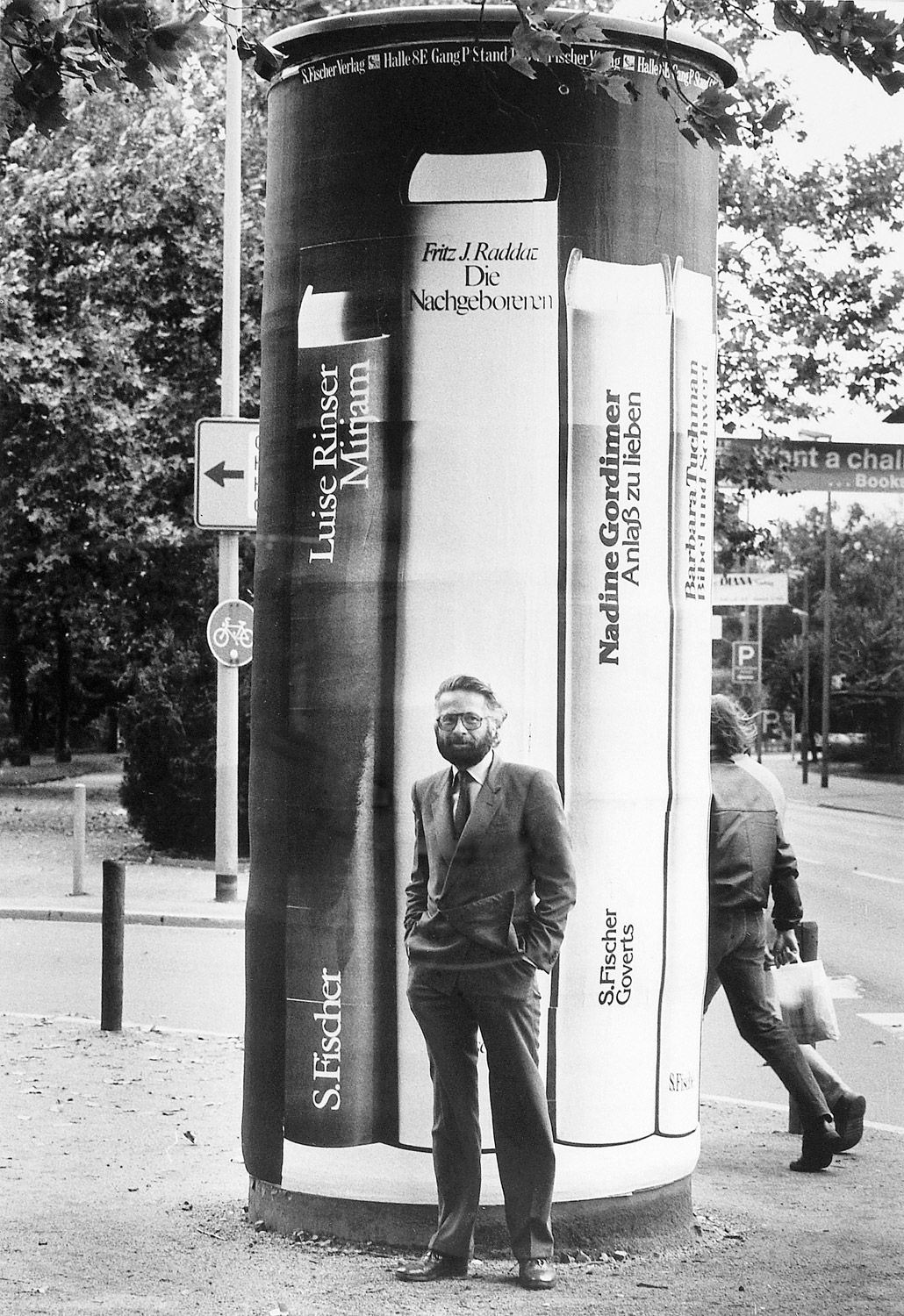

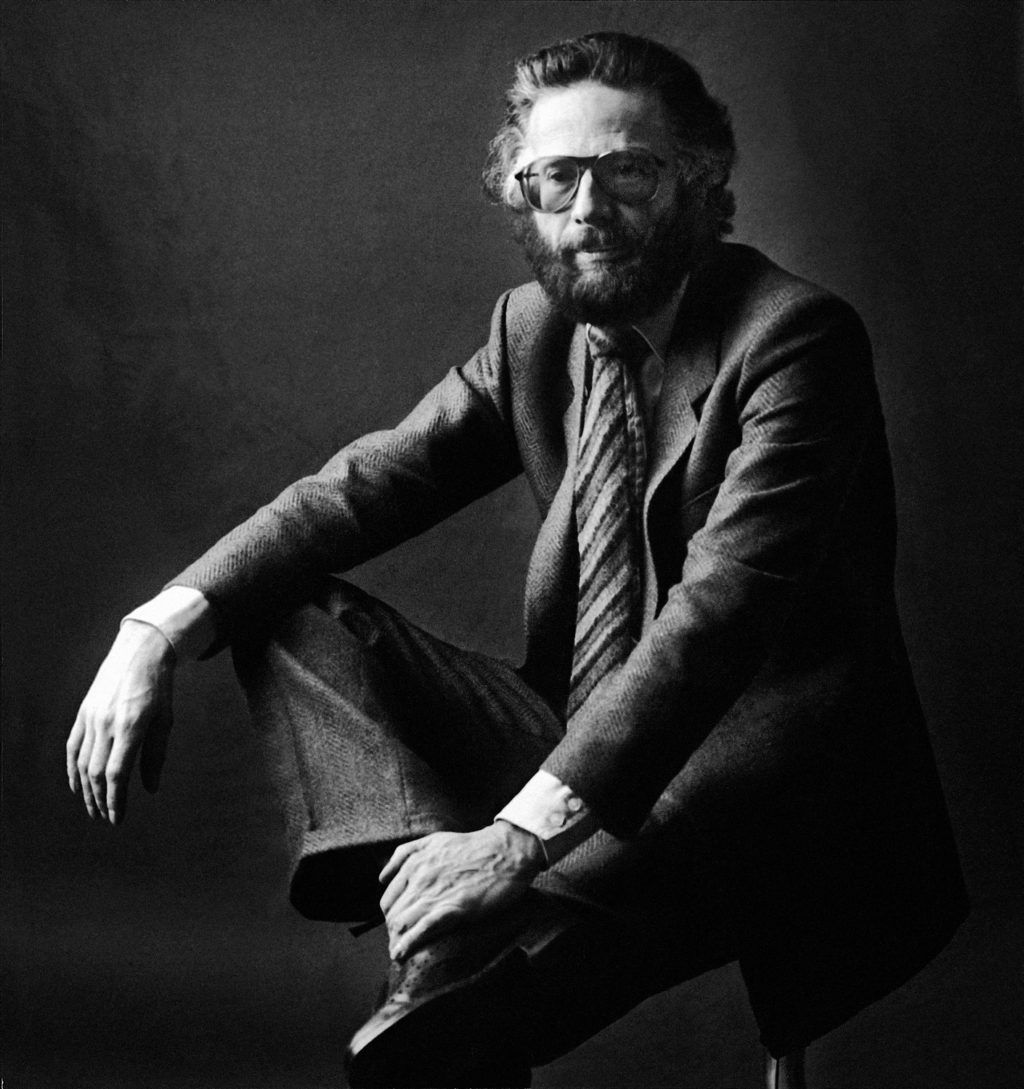

He was, quite possibly, the brightest – and certainly the best dressed – culture journalist Germany had ever seen. As a major player at the respected weekly Die Zeit in the 1970s and 80s, he shaped the cultural life of West Germany. Always on the Left but never a “lefty,” he drove a Porsche when it was more fashionable to go to demonstrations. He brought James Baldwin to the Germans, and interviewed everyone from Jean-Paul Sartre, to Gabriel Garcia-Marquez, Susan Sontag, and Francis Bacon, maintaining a peculiar intimacy with every person of cultural importance in Germany at the time – and a fraught, love-hate relationship to his entire industry. He just turned 80 years old, and the German media is only now realizing just how much they miss him. This is a portrait of publishing iconoclast FRITZ J. RADDATZ.

It is rarely clear whether a critic is being friendly or disdainful; no one has better mastered that ambiguity than Fritz J. Raddatz. We first met when I was working for Die Zeit, where I had immediately gotten the sense that I would never be old school enough to feel comfortable there. I had been assigned to interview him about his art collection for a small magazine, something I had agreed to only because I rarely refuse those sorts of things. (It’s important to keep doors open.) Of course I had an idea of who Raddatz was – his legend preceded him – but never before had I encountered a journalist so keen on drawing attention to himself, and yet so likable. I was drawn to him as to a kind of extinct species: the editorial peacock, strutting amidst the newsroom riff-raff.

This was around 2005, if I remember correctly, and Raddatz was wearing a light yellow shirt, a dark yellow pullover, and a somehow shiny ochre jacket, accented, of course, with a folded handkerchief in his breast pocket – an indispensable accessory, no doubt. Below the belt were pleasantly beige trousers, and the requisite loafers. Raddatz looked around at the office as though it still all belonged to him. “So, this is where you sit,” he said, scrutinizing the dismally gray office I shared with the somewhat famously fearsome Iris Radisch, as though trying to place me, rookie literary editor. When the secretary came in she seemed pleased to see him, which vaguely pleased Raddatz, too, and spread a somewhat restrained cheer about the room. Raddatz’ departure from this place had, after all, been sour – Raddatz who considers “journalist” to be a swear word, who scorns those who serve sparkling wine instead of champagne. He was, as one-time Editor-in-Chief of Die Zeit Theo Sommer once noted, “not only brilliant, but wanted to be brilliant at any cost.”

GEORG DIEZ: You do not seem like a collector.

FRITZ RADDATZ: How do collectors seem?

They carry masses of luggage, for one, and you look like someone who likes to travel light.

I am more of a sensual collector – not a rich heir or a screw manufacturer who buys art with his inheritance. “Collection” is almost too lofty a word for the things that I have carted together.

Max Beckmann, Miró … a watercolor by Henry Miller …

Those are all things that have come out of my work and friendships with artists. They thrive from a dialectic, even fetishistic relationship. I have written about artists and worked with them; they have given me something back in return. It’s that exchange that makes their energy magnetic.

Does your collection relate to your experience of war and the division of East and West Germany, and how fleeting it can all be?

No doubt. Retaining things is an attempt to outsmart death, in the same way that creating things is. The sculptor Alfred Hrdlicka, who I was friends with for a long time, once told me that every day spent in front of his marble was an attempt to defy death. Every artist wants to leave behind something of himself. Perhaps we deceive ourselves, but when acid eventually corrodes all the papers I have stored in the Marbach Literature Archive – my journals, manuscripts and so on – I should like a shadow of my life to remain.

And yet you always seem to be on the go – on the run, even.

I’ve had a very unsettled life, it’s true. But collecting is not a reaction to this. Collecting is an attempt to caress and to be caressed, to protect things and to be protected by things.

To have something watch over you.

Like my marvelous Lynn Chadwick sculpture of a wolf, which stood for years in the apartment of the writer Joseph Breitbach, with whom I was highly argumentative, but also quite friendly. It now stands over my fireplace.

What about that Porsche you used to drive – surely that was a thing you enjoyed purely as a thing?

I haven’t driven a Porsche in decades – that would be ridiculous at my age. I would sooner wear a pair of shorts. But whether it’s a Porsche, a Bentley or the Jaguar I currently drive – which is also a nice car – it is indeed just an object. Once I drove the Jaguar to see the sculptor Arnaldo Pomodoro and he said right off the bat, “Bella macchina!” He just understood the beauty of this object!

You are a true aesthete, then.

Do you know the quote from Oscar Wilde, “Appearances reveal our true insides”? Still with a pair of custom-made shoes, or an 18th century Venetian glass, or a Jaguar, I maintain that it is someone’s creation that someone has made. Gottfried Benn has a wonderful poem called “Reality” that expresses precisely this thought: “When he felt dread, a fetish he made/ when he suffered, the pietà he completed/the tea table he painted while he played/but by then the tea had been depleted”…

So it is a spiritual, totemic thing?

There is a creator behind every work of beauty – or as the artist Paul Wunderlich once told me, “That which stands or hangs here did not previously exist in the world.” This thought is somehow enormously exciting to me.

So there is creation on the one hand, and nothingness on the other – as Benn says, fetish is born of dread.

Well an artist is always vis- à- vis de rien, always naked in the face of nothingness, always at “zero.” You have an empty page or a lump of clay and then someone comes – be they genius or faiseur, as the French say – and transforms it into something that didn’t exist before. The desire to create something beautiful on top of that is all the more fascinating.

Is art the beauty of saying “me”?

Art is the courage to say “me.” The beauty is a side-effect.

After a long-lasting conflict with GDR government and party officials, Raddatz was arrested in 1958, then publishing manager for Aufbau Verlag in East Berlin. Soon thereafter, he left for the West, taking up a position as executive editor of Rowohlt Verlag in 1960, on the other side of the wall. There he published the likes of Hubert Fichte, Isaac B. Singer, and Walter Kempowski, to name a few, yet by 1969, he was ready to leave – and his colleagues were ready to see him go. “They couldn’t stand me there,” he later said.

This is not surprising, if you understand the social and sexual politics fueling the German media at the time – and the status and function of literature in post-war Germany. Back then a group of young writers known as Group 47 gathered regularly and ritually. Their goal was to break with the past and move German literature, and the country at large, into a new era. Art, they thought, rather romantically, could better people. It could certainly help them overcome their guilt – for their Nazi fathers, their time as young soldiers in the Wehrmacht. They would embody a better Germany, and in doing so free themselves from the past, in the way others did through consumption and a miracle economy. It was only in such a tense atmosphere that the conflicts around Raddatz and others, such as Gunter Grass, Uwe Johnson, Hand Magnus Enzensberger, and Martin Walser, could unfold as vehemently as they did. Raddatz still accuses Grass of unappetizingly “whoring around”; he finds Enzensberger “cynically cheerful,” however, in a good way.

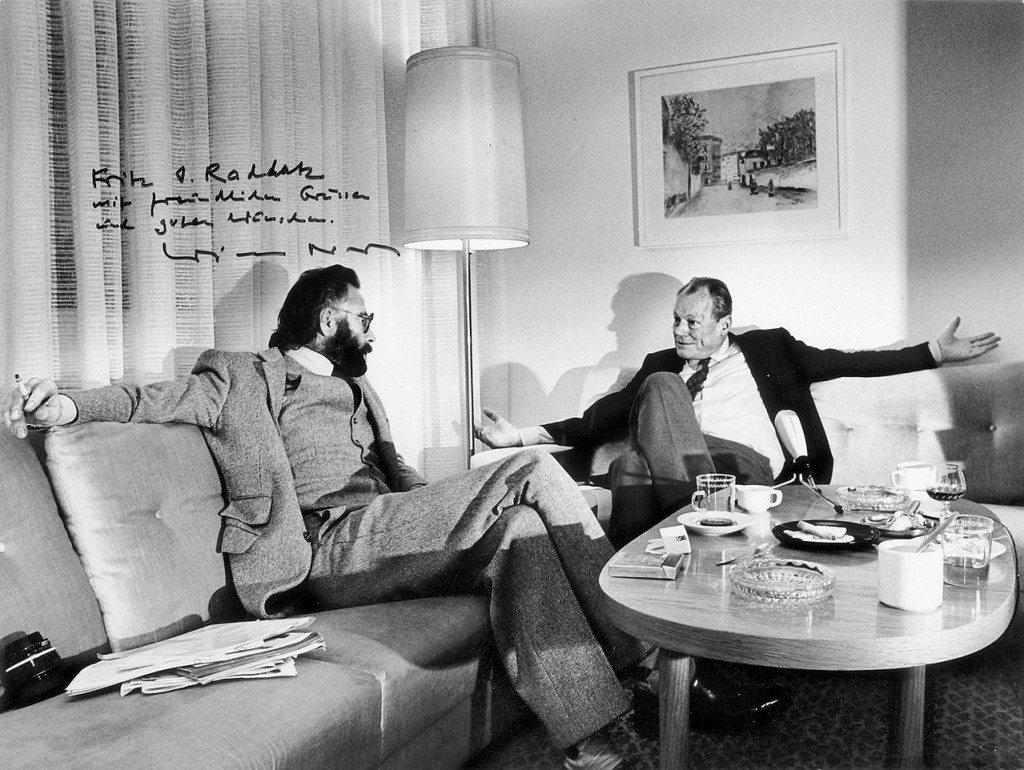

Raddatz was pleased by Germany’s reunification; although it is, to him, “ultimately a disgusting country,” he advocated for the fall of the wall, in particular in an article in September, 1989, weeks before it actually happened. “I refuse to have a utopia ban imposed on me,” he wrote, chastisingly. “It is not true that history is spurred on by ‘realistic politicians.’ Behind that theory lies an ‘I-assume-so’ mental laziness and laggard heart good only for milk money, emission levels and EU chicken-leg quota regulations.” How pleasant and exhausting this man is, I thought, as we discussed Bertholt Brecht and Heinrich Heine that afternoon in Hamburg years ago.

FR: Look at Brecht’s chin. It reveals something of the brutality with which he dealt with women. And the eyes – you can’t tell if they’re closed or open. But that is part of the lurking, the scheming, the cleverer-than-thou quality that Brecht had. Everything is there – the loving and the critical – and I find that marvelous.

Doesn’t it hold something disingenuous, something lazy, the intellectual’s dilemma?

Disingenuous, yes, but never lazy. Just think of Brecht’s Buckow Elegies. Politically, he was indeed disingenuous, with his “Dear Comrade Ulbricht,” and so on. But who isn’t? Gottfried Benn certainly was; even my little god Kurt Tucholsky was disingenuous, privately and politically – there were some very unpleasant things from the beginning of World War I, for instance.

Such is the mask of art.

I think no one is without lies, but the question is, is the artwork a lie? Art can certainly reveal a lie or integrate a lie. But if the work of art itself is a lie, then it is no longer a work of art.

Is this why Heinrich Heine is dearer to you than Brecht?

I have my reservations about Brecht, it is true – even though I love many of his poems and, unlike a few of my very clever colleagues, still value his plays, and not just the Three Penny Opera. But Heine is much closer to me, with his playfulness and narcissism and coquetry and irony. It never would have occurred to me to write a book about Brecht …

But you wrote about Heine, and you also wrote about Marx. Your biography of Marx was one of the reasons you had to leave East Germany: it proved you were ideologically unreliable.

Throughout my life, I have always had to go. I was always thrown out of everywhere. In East Germany, I was imprisoned. That is the difference between the East and the West: there they jail you, here they throw you out. That almost always happens, by the way, in nine-year cycles. First, forgive me, people admire me, then they can’t bear me. I was thrown out of Rowohlt first, although a close relationship existed between Heinz Maria Ledig Rowohlt and myself, a kind of professional marriage. And it was the same at Die Zeit. For years now, I have not been “in” anywhere, so at least I can’t be thrown out.

I saw Raddatz again several years later, in 2010. We were on a train back to Hamburg from Sylt, where he had gone for a little getaway, and I was traveling with him for a portrait in Der Spiegel, my new employer. “Vanity is a productivity motor,” he told me. His diaries from the years 1982 to 2001 were about to be published that fall. Simply called Tagebücher, the collection somehow emerges as a novel from the black heart of West German society, full of manners and bitterness, bile and praise, with echoes of a fractured, gay Bildungsroman – a dark romance between a man and the culture he feared would eventually be his undoing. “The petty bourgeois,” Raddatz coughed, “they were envious that my suit had a better cut than theirs.” He was amused that people continued to write about his socks and cigarette case, so foreign was his aesthetic ego to his compatriots. “This feeling,” he wrote in his journal, “of not actually belonging anywhere, of not being carried by anyone, of always being an animal of the wrong (or without any) pedigree – that scraped my nerves.” And he was, of course, eventually cast out.

He asked in his journal in October 1985, “What is it that makes me so terribly despicable? Its origin cannot possibly be the age-old criticism of a certain kind of car, the shirts from England or the pictures hanging on the wall.” Could it be, he wondered, his homosexuality, his “Jewishness,” or rather his perceived superiority that was too much, and too often flaunted? A scandal broke that very day that would cost Raddatz his job as cultural section head at Die Zeit. In a small editorial about the Frankfurt Book Fair, he had placed Goethe in the age of the railroad – something of a felony in Germany. Other newspapers picked it up; Raddatz stepped down. He maintained an office and a salary at the paper, however. “Spooky, my premonition,” he noted in his journal. At least his belief that post-war Germany was in fact governed by “everyday fascism” had been confirmed.

The fact is that during the eight years in which Raddatz shaped the arts and literature pages of Die Zeit, Raddatz had almost left – or been cast out – many times before: once for attempting to print a letter that Böll, Dutschke and Marcuse had written to the Red Army Faction, at the height of the German public’s left-wing terror frenzy, and again following a write-up of the movie Das Boot, in which Raddatz located self-pitying soldier pathos. The latter offense caused his publisher, Gerd Bucerius, to issue a public response in which he called Raddatz “unbearable,” among other things. Such drama, played out by the tight-knit, antagonistic, tail-biting moguls of the Hamburg media, forms the better part of his Tagebücher. One is confronted by an insular, almost courtly world, dominated by jealousy, ego, and intrigue – a kind of Rococo on the Alster river, complete with tyrannical excesses. It was a generation that lived fast and ran away faster – from the war-guilt of its early years. Once safe from Nazi murderers, they devoured books and slurped oysters, developing their image in the years of ruin following conflict, and becoming men as part of Germany became a democracy.

Raddatz’ father forced him to have sex with his second wife – Raddatz’ step-mother – when he was young, a “moment that determined and ruined” the rest of his life. The experience is recounted in his novel, Kuhauge, which was slammed at the time of its release in the late 1980s, critics once again citing Raddatz’ ego as an Achilles’ heel, of sorts. Yet his outsider-status – biographically, sexually, intellectually – is what made him what he was. His French mother died at birth; his Ger- man father beat him. Raddatz grew up to love both men and women (but men more). That bisexuality made him more vulnerable, he explained to me: “The ‘real’ gay is more comprehensible than someone who is debauched with both sexes.” “The pit of the peach remains lonely,” he says.

A friend of Raddatz tells me, “he has settled into his existential sadness.” “He has signed for every moment of sadness like an expensive piece of furniture, and his passion for collecting overwhelmed him in the end.”

What is happiness?

In my ability to feel happiness, there is always melancholy, too. But there is never this feeling of, “Oh, God, why didn’t I become a Benn, a Thomas Mann, an Adorno?” That doesn’t interest me. I just became Raddatz.

Is melancholy a part of every artwork?

I feel melancholy when I view and touch a work of art – because sculptures have to be touched; they have to be caressed and experienced and felt.

But one senses a disquiet in you, a desire to be something else …

I was very close to the writer Thomas Brasch, and his death upset me immensely. But he had hung my last letter to him over his bed, and it said, “Put an end to the struggle with yourself.” Of course by that I meant, “stop using cocaine”…

And he didn’t listen. But what Breitbach, and his lonely wolf?

Its hunger and humor and evil convey how our relationship was. He wrote in his will that I should choose something from his treasures – he was quite wealthy – but I didn’t want any of the Napoleon III antiques. They didn’t hold anything of him – his spirit flew out the window and vanished when he died.

So you chose the wolf.

His spirit was in it – in this totem, if you like. If I am lucky, this will reach out and spark something within me. Happiness, the sadness of striving in vain, the lovliness of the double-meaning of that word, “vain” – art invokes all of that in me. In the evening when I am sitting in front of an object drinking my red wine or smoking a cigarette, it happens to me that it brings together all the questions and all the fears that exist. Confronting one’s own death at my age is not unrealistic.

How do your friendships function with all this conflict?

Like a tree acquiring rings. Or, like lovers – in the beginning you are curious about each other, but after 20 years the interest in sex diminishes somewhat. Or so I hear. I, of course, only know this from books.

Credits

- Text and Interview: GEORG DIEZ