Capturing Psyche: LEONORE MAU

|INGO NIERMANN

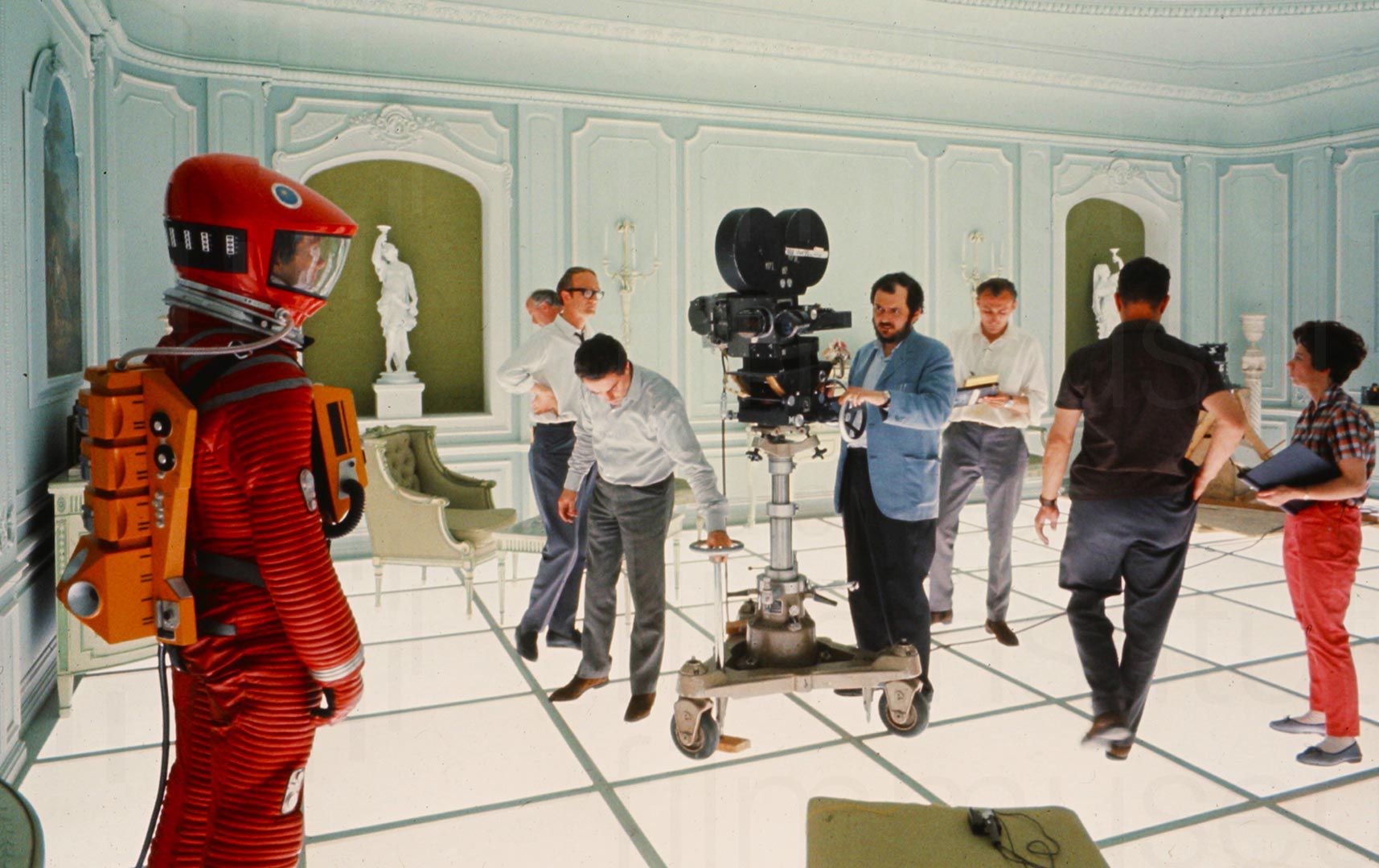

LEONORE MAU’s photograph of the young African boy from the Royal Court of Abomey is both a simple scenario of a child playing with the debris of modern civilization, and a chilling alien image from science fiction recalling the black monolith of Kubrick’s 2001. He is somehow all-seeing and all-knowing, like the Angel of History who turns unmistakably towards the future. Here, Mau speaks about the rituals and ethnographies that steered the latest in her series of three books, Psyche.

LEONORE MAU: At that moment, for the first time, we had enough money.

INGO NIERMANN: Hubert Fichte had published the novel Die Palette (The Palette).

Yes, and he earned quite a bit of money with it. Then we bought our tickets, at first for a short journey: three months, not long.

And why did you decide on Brazil?

Because we knew that the most beautiful rites were in Brazil – from the Candomblé – and because we could speak Portuguese. We went through a favela at night, always following the drumming. Wherever it sounded the loudest and most beautiful, we’d stop in front of a hut. But we didn’t go in; instead, we waited. The people have the sixth sense – or the seventh or eighth – and after two minutes, two of them came out and asked us what we were looking for. We could answer them in Portuguese, which put them in a friendly mood right away. And they asked us to come right in. I asked if they’d allow me to shoot some photographs, too. Then they talked with each other for a while without realising that we understood perfectly well what they were saying. What they said was, “Here are two people from Europe and the woman wants to shoot photos. But she can go right ahead, and since the gods won’t allow it, nothing will appear in the photos.” But the gods allowed it after all; it was all there. After the three months were up, we decided to raise money to come back for a full year because the most important festivals happen throughout the year. And we photographed all of them.

The interest in African-American religions not only led you to Africa; you also took with you a message from the priestesses of the Brazilian temple Casa das Minas, which is said to have been founded 300 years ago by an enslaved daughter of the King of Abomey, to the Royal Court of Abomey in Benin.

Everyone in Brazil knows what the Casa das Minas is. The priestesses enjoy great prestige. They gave us a message and a tape with a recording of their singing to bring to the Royal Court of Abomey. As a sign of his ambassadorship, Hubert Fichte received a colourful glass necklace. Every colour and the position of each glass piece in relation to the others represents something in particular. Once they looked at the necklace at the Royal Court and listened to the singing on the tape, they took a large sheet of paper and wrote an invitation to the priestesses of Casa das Minas.

They understood the Brazilian singing and the necklace?

Yes, it really impressed and moved them.

“I’ve always stood by the rule I set up for myself to never become the unwanted photographer collecting people.”

Did the priestesses follow up on the invitation?

I don’t believe so; I would have heard about it one way or another. The priestesses of the Casa das Minas told us that they would have to go to Abomey at some point eventually because something was missing in one of their rites. So Hubert Fichte said, “Then we’ll begin right away. Twice a week, we’ll study French.” Hubert began to teach them French and it was going along very well, but then he died.

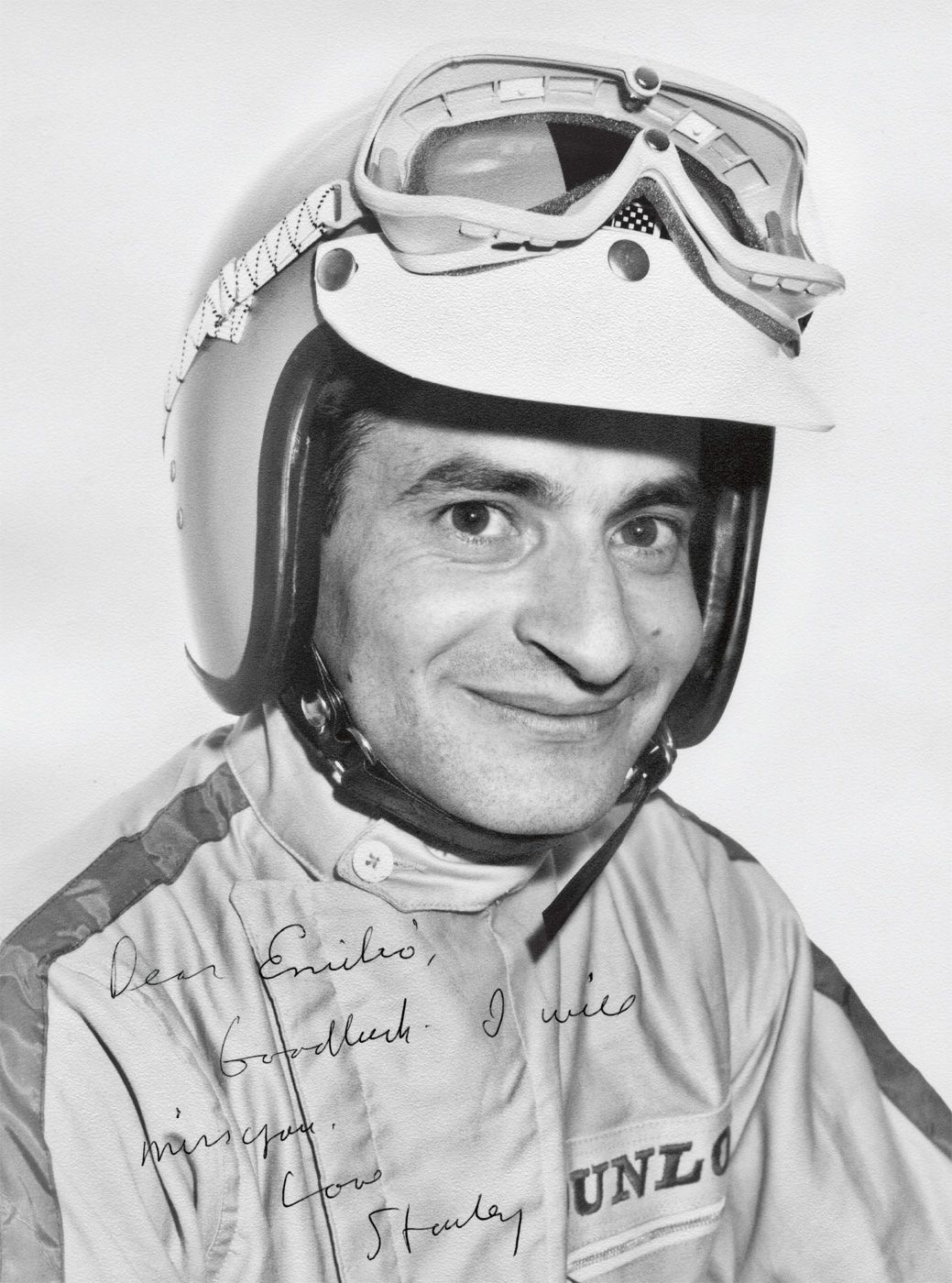

Near the Royal Court of Abomey, you also did the fascinating and disturbing photo of a young boy who was wearing an empty package of pills as a mask.

We were standing on the street and looking around. Suddenly I saw the boy standing there. I asked him to stand still because I’d like to take his picture – which made him very happy.

Have you never taken a picture without asking first?

No, I’ve always stood by the rule I set up for myself to never become the unwanted photographer collecting people. I’ve always asked first, and at ceremonies as well. Whenever we heard that there was a temple here or there, we went first without a camera, introduced ourselves and asked if we could participate. And when they agreed, we stayed through to the end. Not shyly, like tourists peeking in on things, but sometimes really for twelve hours at a time.

There were times when I wasn’t there with my camera when someone would ask, “Where’s Kodak?”

There’s a description by Hubert Fichte in his book, Petersilie (Parsley): “A boy has tied on an airplane, blood-smeared metal, mirror shards. He’d bound bulging lips pierced by boar horns to his face, which he took off when Leonore wanted to photograph him.”

That could very well be because there is a superstition – very strong in Islamic countries – and you have to be very careful because they believe you’re taking their person away from them. I never insisted – “But I want you to, please do this.” I never had any sort of difficulties because I always respected that. But on the other hand, there were also times when I wasn’t there with my camera when someone would ask, “Where’s Kodak?”

Was there ever a time when someone allowed you to make photographs, but it nevertheless seemed indiscreet to you?

The line between indiscretion and fascination is very, very thin. In Brazil, there was a huge, catastrophic rain. It rained for days and all the favelas were sliding down the mountain, and for days, we couldn’t get out of the little house we’d rented because it was surrounded by water. When I was finally able to get out and head towards the centre of the city with my camera, there were several dead bodies in the streets, completely swamped with mud. I was just about to photograph them when the police saw me with my professional equipment – and they immediately lifted the sheets that had been covering the dead. They practically requested, with friendly gestures, to take a picture. And I did – it appears, very small, in Xango, the book of photographs, along with this story.

In West Africa, in the ’70s, you shot photos of the mentally ill who were being held in public places. Didn’t they feel like they were on exhibition?

On the contrary. They were excited to have so many people paying attention to them. No problem at all. That was in Togo or Benin. The people who – as they say – weren’t normal, they weren’t put in clinics, but instead, staked out on the public squares. That way they’re still part of the community; people talk with them. The children in particular like to talk to them and they like to talk to the children. Naturally, the people laugh at them at times, but they’re never mistreated. We really observed that closely and spent a whole day in such a village. No aggression. Of course, it is horrible, but they don’t have money for a hospital. And ultimately, when you think about it, one can be declared insane by society – it goes very quickly – and then you lie there all day, more or less looking at nothing but white walls. That’s a perfect way to go insane. In Africa they also have completely different explanations for mental illness; for example, the mistreatment of dead family members. If someone breaks the rules of the society, it doesn’t mean he’s exiled right off. You’d really have to be raving mad before they’d say that he’s sick.

“I don’t see myself at all as an ethnographic photographer, but instead, as a photographer who takes pictures of what completely absorbs me.”

How did you get involved with mental illness and psychiatry in West Africa?

In Senegal, there were many intellectuals we spoke with and they told us about the famous psychiatric school in Fann and accompanied us there as well. We were there for three weeks in 1974. Fann was overseen by the French professor Henri Collomb. We also flew with him in his small airplane to Casamance, to the psychiatric village he founded. The village was constructed in such a way that the sick could live together with members of their family. They had their own little straw houses and could cook there as well. Once a week, the doctors would meet with a patient and his family for Pinth, which means “coming together” in Woloff. The case would be discussed and most of the doctors only spoke the colonial language, French. Only one could speak Woloff; he was married to a Senegalese woman. Hubert Fichte wrote a text about it, “Gott ist ein Mathematiker” (God is a Mathematician). If you can’t speak with someone who’s been declared mentally ill in his own language, that’s insanity to the third degree.

What are your thoughts regarding traditional healing as compared to modern Western psychiatry?

I can’t really say all that much about it since I can’t compare the results. But the fact is that a tremendous amount of care is given to the ill in traditional African therapy.

In an interview with Hubert Fichte, Henri Collomb said that Western psychiatry was taking care of people in Africa who in earlier days, because they couldn’t be subdued by traditional means, might have been driven out into the bush or even killed.

In Fann they use medicines which are used here as well, but in entirely different dosages, and some of these medications are really quite bad.

You also photographed the administration of electric shocks.

I thought to myself, “You have to photograph this.” This is something that Collomb had actually declared inappropriate for the hospital in Fann. But there was still an old pavilion in which that was done. It was horrible. The plug was simply stuck in the socket in the wall and then something broke in the brain.

There’s something of a renaissance for electric shock treatment going on now.

Yes, I’ve heard that.

Although not in such high doses.

Something’s being measured, but the brain is still a secret and there’s much of it that still hasn’t been explored.

Some of the doctors say, in an interview with Hubert Fichte, that they administer electric shocks not only because medications are lacking but also because family members specifically ask for it. For them, an electric shock is comparable to the death phase of an initiation.

Only something gets broken in the brain and even people here in Europe don’t know that.

You also photographed a particularly intensive traditional healing ceremony in Senegal, the N’Doep.

A mentally ill person has to sit on a steer. Then the steer is killed and, with it, they are … you wouldn’t say “buried,” but several sheets are thrown over them and all they have left is a small hole for air. Afterwards, the blood is rubbed into them and the intestines of the steer are wrapped around them. So it’s something of an odor shock therapy. It’s such a shock that many do return to normal life. Just imagine, you’re buried with a dead steer and then its blood is rubbed into you. And then they have to dance for hours on end. They’re never left alone, and this goes on for a full week. And if they didn’t have success with this method, they wouldn’t do it. Then the people would say that you’re crazy. But it works.

In Explosion, the novel about your trips to Brazil, Hubert Fichte describes how you tried to find all the ingredients for an initiation drink – which is practically impossible because there’s an incredible number of different terms for them or the same terms for the different ingredients. Just before your return, you drink this uncertain solution. Do you remember this?

Oh, yes, I still remember. On the plane, something was itching me and I wanted to reach it, but my hand landed somewhere else entirely. After two days, everything was back to normal.

Did you also have rituals conducted for you?

No. We were very strict about that. Hubert Fichte once told a priest in Venezuela who’d begun sticking him with needles: “If you do that, we’ll never come back.” We would write about it and photograph it, but it would be impossible in such a short time – it would be a complete lie to decide to take part in it. At the most, and there’s a very fine photo of this, a priest in the end, at six o’clock in the morning, touched him once on the forehead with a bloody finger. Besides, when you’ve got a camera, you’re somehow also protected from being taken away with it all. Something happened to me when we were in Haiti for the third time and were invited to a ceremony by a voodoo priest. It’s fantastic, their drumming, and after three hours, I thought, “What’s going on?” I’d lost all my strength; Hubert Fichte was just able to catch me. So I’d fainted, in a way. That never would have happened to me if I’d had my camera. You’re so awake then. But without it – naturally, they were very happy to have this white woman see what it was all about.

The most famous German ethnographic photos are surely the Nuba photos by Leni Riefenstahl.

Yes, as photos, they are remarkable. For me, they’re very nearly advertising photos, too beautiful, really. But she’s an incredible person. The way this Nazi story hangs around her neck, that’s her bad luck. But the film about the Nuremberg rally is ingenious because she documents how the Nazis turned the Germans into a machine, a functioning machine. Let someone else follow her and try to show that as well.

Leni Riefenstahl also lived with the Nuba.

There’s this amazing photo where she stands on a sandy path with a buck-naked Nuba twice as tall as she is.

Even if you, as a photographer, have the feeling that you’re not really present – the observed person perceives that you are and might act differently.

I can’t be the judge of that because I can’t be there when I’m not there. Just doesn’t work, unfortunately. The lines between objectivity and subjectivity are completely fluid. Objective, subjective – it’s an invalid differentiation. I can only photograph what fascinates me completely. Someone I have no relation to whatsoever, that’s going to be a bad photo. And it was the same way with the rites. I also don’t see myself at all as an ethnographic photographer, but instead, as a photographer who takes pictures of what completely absorbs me. In photography, one is engaged in the moment in which one takes the picture. Either you’ve got it or you don’t. Especially when it comes to the ceremonies. I’ve never said, “Do that again.” That’s nonsense, it doesn’t work. But someone who writes can make notes or has something in their mind and can work it out in peace – or in not so peaceful moments. But a photographer can’t do that.

What was the relationship between the word and the image for Hubert Fichte? Did he also not see a sort of competition between his texts and your photographs?

No, he loved to describe things thoroughly. And if he didn’t, we wouldn’t have stayed so long in Brazil, for example, or anywhere else. He always said, “You’ve still got to get this and get that.” The famous blood bath – it was great fun for him that I got that. Hubert Fichte reacted entirely positively to my way of taking photographs.

What do you mean, positively?

He talked with me about it and was very helpful. But he never touched a camera because he said that he never wanted to take a picture in his life. But the best photos of me were taken by him.

What do you mean?

Exactly what I’m saying. We were once sitting in a train across from each other. The train was completely empty. And then he said to me, “Focus the camera on me and then give me the camera and I’ll take a picture of you.” That’s exactly what happened and it’s one of the best photos of me ever taken.

“In the decay of language, which we’re seeing now, one has to, I think, have a relationship with language.”

Hubert Fichte’s magnum opus, Die Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit (The History of Sensibility), begins when Jäcki, a homosexual, and Irma becoming intimate with one another. It isn’t difficult to see the two of you as Jäcki and Irma. Is it not uncomfortable for you to be revealed in such a way?

No, not at all. I’ve been asked that many times. In interviews – one Spiegel editor began just that way – conversations between the sheets. I said, “I’ll not say another word.” But literature is literature. There, I’m fully on the side of the word. When someone writes well, they can write anything and everything. In the decay of language, which we’re seeing now, one has to, I think, have a relationship with language. That’s why this country doesn’t have any power anymore: the language is decaying. It’s not credible anymore.

When did that begin?

I think it’s the result of losing two World Wars. A country doesn’t overcome that so easily. And from the aging population – I’m not exactly a spring chicken myself anymore, either. But conscious awareness, being and observing, that’s still very important to me.

Hubert Fichte died almost twenty years ago. Why is Psyche, the book of text and images you made together about the mentally ill in Africa, appearing now for the first time?

The publisher released Xango and Parsley, two books of text and images about African-American religions, and it was supposed to have been a trilogy. Then Hubert Fichte’s illness became worse and worse and he had to go to the hospital and, after the first operation, I received a letter from the Fischer Verlag, saying that they had a new marketing person who’d done the math and said, “Are you crazy, it’s going to be too expensive.” And then we received a heart-rending letter saying they would go ahead with it anyway, etc., etc., and in the future … all these promises and they never lifted a finger. I then set Psyche to the side and signed the contract for The History of Sensibility. Then, for the next three or four years – I could barely type at all anymore – I typed up the book, Explosion. That’s over a thousand pages and in a handwriting that’s very difficult to read. Photography for me, then, was out of the question for a while. But all the books came out.

Why did it happen that Psyche is coming out after all?

Ronald Kay, Pina Bausch’s partner – I’m very good friends with her as well – looked at the slides and said that we have to make a mock-up. We made laser copies of all the slides. A year ago, Frau Schöller, the publisher, received the mock-up and saw these images for the first time and decided then and there to realize the project. That’s how excited she was.

Are you still making photographs?

Yes, photos I create myself. Out of plants, shells, whatever is around in the house. They’re called Fata Morgana.

“I don’t know how people can stand it, sitting here in Germany all the time.”

Don’t you miss taking photos on trips?

Yes, of course. I can’t at the moment because with both knees operated on my walk is pretty weak. But if I were to be invited now, I’d go immediately. If I had the money to pay someone to come with me and carry the camera.

Even if it’s far?

Yes, the long flight – you’re served, you see a film, you’re happy to be going so far away, you can look out of the window. What’s so terribly hard about that?

You financed your trips by doing work for newspapers, magazines, and radio.

Yes, we planned and worked that in, and there was always a time during the day when we sat on the phone for one or two hours. But then, away. I don’t know how people can stand it, sitting here in Germany all the time.

But you never thought of moving away for good?

No, and not simply because of the language, either.

You’ve been living in your current apartment almost since you moved in together with Hubert Fichte.

I could cast the owner of this building in gold, really. Fine, the building needs to be renovated, but I don’t really care. This person has never raised my rent since Hubert Fichte’s death – as a matter of decorum. I’ve got a huge place here, a darkroom and it’s truly a beautiful apartment. What day is today?

The first of April.

Hubert Fichte’s funeral, April first.

Do you usually visit his grave?

I’m not one to visit graves, and Hubert Fichte wasn’t either. We talked about that once for a long time. He was very close to his grandmother and was very sad when she died, but he said that he’ll never go to her grave. I’m not quite so extreme about it. I had a very beautiful stone laid at the grave with a carved quote from Empedocles, whom he loved so much. I still remember a completely empty beach in Brazil and seeing him suddenly with a stick in his hand, and he’d etched this sentence in the sand: I was once a young boy, a young girl, bush, tree, bird and fish.

Leonore Mau, born in 1916, began her career as a photographer in Hamburg after the WWII. In 1961, she moved in with the homosexual author Hubert Fichte, born in 1935. The two went on several long journeys together, particularly to Latin America and Africa, until Fichte’s death in 1986. Two books of texts and images they created together, Petersilie (Parsley) and Xango, have appeared in which Mau and Fichte document African-American religions. Psyche, a third volume on African psychiatry followed in 2005. Mau passed away in September 2013.

Credits

- Interview: INGO NIERMANN