ARIA DEAN Life World

|Octavia Bürgel

“I never really wanted to be a curator, like, at all,” Aria Dean told me when she visited the 032c Workshop in January. We had last seen each other the previous July, gossiping over damp pizza in the garden patio of a favorite Brooklyn restaurant during an unpredictable summer deluge. When she passed through Berlin on her way back to New York from a speaking engagement at the Museum für Moderne Kunst’s “Performing Society” symposium in Frankfurt, the atmosphere was cold and dark, due both to the season and to my solitude: I had just moved to the city and longed for my community at home. “Do people jaywalk here?” Dean texted as she waited for a break in traffic to cross Potsdamer Straße, the question, and her arrival, delivering a much-needed dose of familiarity.

After graduating from Oberlin College – our shared alma mater – in 2015, Dean worked briefly at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art before being appointed to assistant curator of Net Art and Digital Culture at Rhizome the following year. Her first curatorial endeavor for the online platform was 2017’s New Black Portraitures, which considered black representational politics through the prism of digital culture, expanding on the potential and the pitfalls of black life online. In late 2019, Rhizome promoted her to editor and curator, a position in which she aims to “use technology as a lens, or a very light gloss, through which to approach contemporary art and culture.” “Any art,” says Dean, “if it’s engaging with the world–– it’s engaging with technology.”

A practicing artist, the 26-year-old has exhibited internationally. Earlier this year, she was added to the roster of New York gallery Greene Naftali, and selected as one of 30 artists to represent Los Angeles in the Hammer Museum’s 2020 Made In L.A. biennial. Yet Dean identifies as a writer above all, and her essays in journals and catalogues have cemented her hybrid voice as one of her generation’s most relevant. “The art practice grew out of that,” she says, “and for me the two things are deeply intertwined.” She describes her initial approach as “writing to understand something, and making work to test an idea” –– a process that, over time, has smoothed into “mapping connections,” rather than prescribing them.

In her essay “Poor Meme, Rich Meme,” engaging blackness as “collective being,” Dean writes:

When considered on its own, in what to some are the shadows, this collective being is allowed to expand and contract at will. But when society shines a light on it, what is atomized and multiplicitous hardens into the black.

What is implied in the action of “hardening” is the viscosity of the precedent state, relating blackness to liquidity – as an aesthetic of constant mobility and plasticity, as a formal refusal of fixation, and as a legacy of the Middle Passage, in which blackness was shaped on violent oceans, in wet and rotting hulls. Dean’s untitled (footnote to war of position) (2017) is a scar: a cotton branch slicked in polyurethane, a body tarred, a gash on the gallery wall. In pictures, the sculpture’s resin surface appears gelatinous from certain angles and firm from others, enacting a fluid unpredictability. Black tar is at once charred and damp, stubborn and insentient, the traumas of racialized torture materialized. Rejecting binary categorization, untitled (footnote to war of position) is a declaration of “both/and,” a liquid reflection of the materiality and philosophy of blackness, and the charted trajectory between Dean’s practices.

Viscosity is foundational to the processes of printed photography, inherent to the material of silver gelatin. It is paradoxically held that a photo is truth-giving, monumentalizing–– that it crystallizes the ephemeral, the fleeting moment. The black body and the camera’s gaze share an entwined and gruesome history. Early photographs of black Africans circulated within European communities gave credence to colonial claims to the “other,” and fueled essentialist notions of race. In a 2018 essay on Eric N. Mack’s abstract sculpture-assemblage works, Mahfuz Sultan reflects on an abstract composition bearing a portrait of Prince at its center, which he mistakenly interpreted as having been taken during an arrest. Sultan writes: “That I, a black man, wandered into the Kunsthalle Basel and blithely assumed it was Prince’s mugshot is indicative of the form’s tragic ubiquity. The black mugshot is arguably America’s most popular genre of photography and the black celebrity mugshot its most extreme rarefication.” Today, the continuum of photo-representational violence incorporates the ubiquitous phone, dash, and body cam footage of anti-black police brutality. These strains of thought converge with an enormous sense of urgency–– in a culture which lauds the democratic potential of images more than it scrutinizes–– and they culminate with a question:

Is it possible to photograph black people in a way that is not predicated specifically on violence against us?

I think no. I think that we cannot image black people or the black body in a way that will be able to circumvent that relation to the mandate of visibility–– the history–– because it is so multi-layered. On a technical level the camera is a racist object, through the light meter calibrations, film emulsions, and so on. There’s the inherent violence of standing a black person in front of a camera, regardless of who is on the other side. Then there is the interaction between the viewer and the photographic object. Even within the photograph itself there is so much room for violence. At every level the photograph is violent. What I have come to is that all representation is violent, insofar as we retain the idea that there’s a truth-event to the photograph.

There’s a book by Georges Didi-Huberman on the invention of hysteria in 19th-century medicine [The Invention of Hysteria (MIT Press, 1994)]. He suggests that the birth of photography took place largely in French mental hospitals with women who were brought in for hysteria. Basically, the doctors would watch these women and take notes on the way they were arching their backs and screaming, and then they would do these photoshoots placing objects around the women that I guess were associated with hysteria. Because of the limited technical capacities of photography and also the gender dynamics of the time, the final product became very, very staged. Didi-Huberman says you can rewrite the history of photography from there–– and that there’s a direct production of subjectivity through that staged image, which is basically how photography continues to function.

So all photographic representation insofar as we believe it is inherently violent. It’s a particularly extra fucked position with black people, because blackness in the West exists coterminously with colonialism and the “New World.” The production of the black subject is so tied to the production of photography that there is no blackness that precedes its photographic image. Ultimately, maybe the question becomes: What are you going to buy into? I think that in film you can fix the violence issue, but not how people think. It’s not through telling stories that are nice about black people. It’s not Queen & Slim. It’s a formal problem.

Continued adoption of digital technologies by black artists, though, creates new modes to repudiate notions of an image’s fixation, right? In your roundtable discussion with New Black Portraitures exhibitors, artist Pastiche Lumumba said: “The future of the Black image is generative, autonomous and ephemeral.”

That was why I was interested in the meme stuff. I think that content-wise you could never repair the relationship to violence within the picture plane of a given image. But formally, in terms of an image ontology, you could try to create a way of circulating, presenting, or relating images to one another in a way that shifts it. But then we can’t just all make memes, that’s boring.

I’m doing a residency in Puglia next year. I had been doing all of this death-related stuff and had heard about Southern Italian death and grief rituals, and the woman who runs the program sent me some stuff on a tradition called Tarantism. Essentially, there is this myth that there is a tarantula in the region that bites women and makes them ecstatic–– very much like the hysteria thing. But somehow it became cross-pollinated with a grief ritual, so when someone dies in the region they do this dance and sing and wail, working themselves into a frenzy. Apparently, when anthropologists went to document the ritual in the 20th century, they did kind of the same thing that they did in France with the hysteria photographs. They produced an editorialized image. But the article I read argues that there is no impoverished reproduction involved, because there’s no real mental illness at the center of it. It was always a mythic, pagan ritual. The whole operation is simulacrum, so it becomes this beautiful copy without an original.

“The production of the black subject is so tied to the production of photography that there is no blackness that precedes its photographic image.”

It’s interesting that you refer to Tarantism as a copy without an original. In “Poor Meme, Rich Meme,”you posit blackness in the same way. For me, it also speaks to a question of permanence. Which holds more permanence: the internet and the digitized world, or the physical, tangible one?

Both places are bad now, I don’t want to be anywhere!

Speaking more generally, everyone is really caught up in the language of “sustainability.” But the word itself really only advocates for “maintenance,” for staying basically the same.

Yeah, moving forward with the least possible inconvenience. What you say about blackness, sustainability, and permanence reminds me of a Fred Moten quote about the black outdoors and escaped slaves–– impermanence being a necessity because you’re running with a “leave no trace” mentality. “Sustainability” rings of longevity, when maybe we can’t keep doing this. Maybe things have to stop. And that means that cities burn, and you can’t have avocados, and maybe that’s just what happens.

Black culture can be understood as one that’s trying to sustain certain things – cultural memory, for instance. But blackness is also the ability to cut through the middle of these binaries. My attitude toward the tensions you mention is that blackness is the thing that militates against the fact that there is a binary. It reminds me of Alex Galloway’s book about François Laruelle, a self-described non-philosopher. It talks about the digital–– not meaning digital networks, but as in zeroes and ones–– as being founded on binaries. I’m really interested in that, because it has a lot of resonances with Black Radical Thought. We sit in the blur.

The other side of the sustainability question, what is defined as “waste?” All everyone talks about is the internet being inundated with “fake news” and misinformation. But it seems we are caught in the same conundrum with physical detritus.

With the climate and with the internet, I’m so depressed by all of it. In the art world we contribute so much to the climate disaster. Everyone is flying around constantly going to stupid biennials and art fairs. Rindon Johnson, who I just worked with on a commission for Rhizome and whose work I love, was doing this cowhide stuff, and a friend of mine who is vegan was like, “I can’t be a part of this because of the ethics of the artwork.” I was like, “That’s really interesting!” I have never sat down and thought about the baseline ethics of the materials used in a given artwork. I guess if plastic is just going to go sit in art storage it’s not really hurting anyone because it’s not going into a landfill, so maybe we should all just be making work out of recycled plastic.

I’ve had this thought, too – like, the one way to stop plastic from getting added to a landfill is to trick art collectors into buying it!

I had total galaxy-brain – like, “Woah, the materials!” I think that we have to just really be okay with the fact that conceptually and materially it’s all going to shit. I go to these art and technology conferences where some journalist is always like, “Did you know that there’s a town in Macedonia? Where kids are making fake news? And they’re tricking people in the U.S.!?!” And I’m like, “Yes, I read that New York Times article.” I’m not really interested in “Isn’t stuff so fucked? Isn’t it all so confusing?” It is all really confusing. But we need new methods of making sense of it. And new tactics to survive. The old methods are just not really working. I think thriving probably isn’t going to happen. Maybe “survivability,” not “sustainability,” is the answer. I sound like I’m at a climate summit.

It’s a conundrum given that art is generally presumed to be so concerned with ethics.

That is one of the biggest problems to me. People really do buy into the idea that we are inherently doing something good by participating in the art world. There is really no reason to believe that. There is no inherent positive social impact that art offers.

I’m really curious to know when that idea began, because that’s not even the origins of Western art history.

I don’t get it! Those were like, decorative objects.

Funded by rich people and the Church!

And, to be totally honest, I think I’m finally ready to go on record saying this: For what reason do people think that it doesn’t make sense that rich people are funding the arts? I’m not saying it’s good! It creates bad situations and unethical problems. It’s not clean money. But people act like it’s an aberration from some actually good system that once existed. When that’s just not true, and it’s very clear that it’s not true.

I had a conversation with an Oberlin person who used to do art stuff but is working in finance now. He was like, “What you do is so great because there’s this good thing that people want, and it’s interesting, and it’s smart, and it could be political, and people want it, and the market…” I had to say, “Dude, what I do is the same as what you do. I’m basically creating value out of absolutely nothing, convincing people that it’s worth something, and they are trading it at a markup.” And he was like, “but because the people want the thing itself, it’s different from finance.”

But do people even want the thing?

I don’t think people even want the thing! There was this misunderstanding–– and I think this happens with a lot of people–– where they think that people buy art because they love it and it means something to them. No, people buy art because it’s a show piece, it’s an investment. The best collectors really do care, and I’m totally here for that. But there’s a willful naiveté that everyone brings to the table.

I don’t feel the need to tell myself lies about what I’m doing in order to do it. I like art because it’s pretty fucked. I like trying to grapple with art, and that’s why I got involved in it. Everyone has their own reasons, and sure, I wanted to express myself. But I wanted to express myself thinking about the building blocks of the world around me, not because I necessarily thought that I was going to do good for someone else.

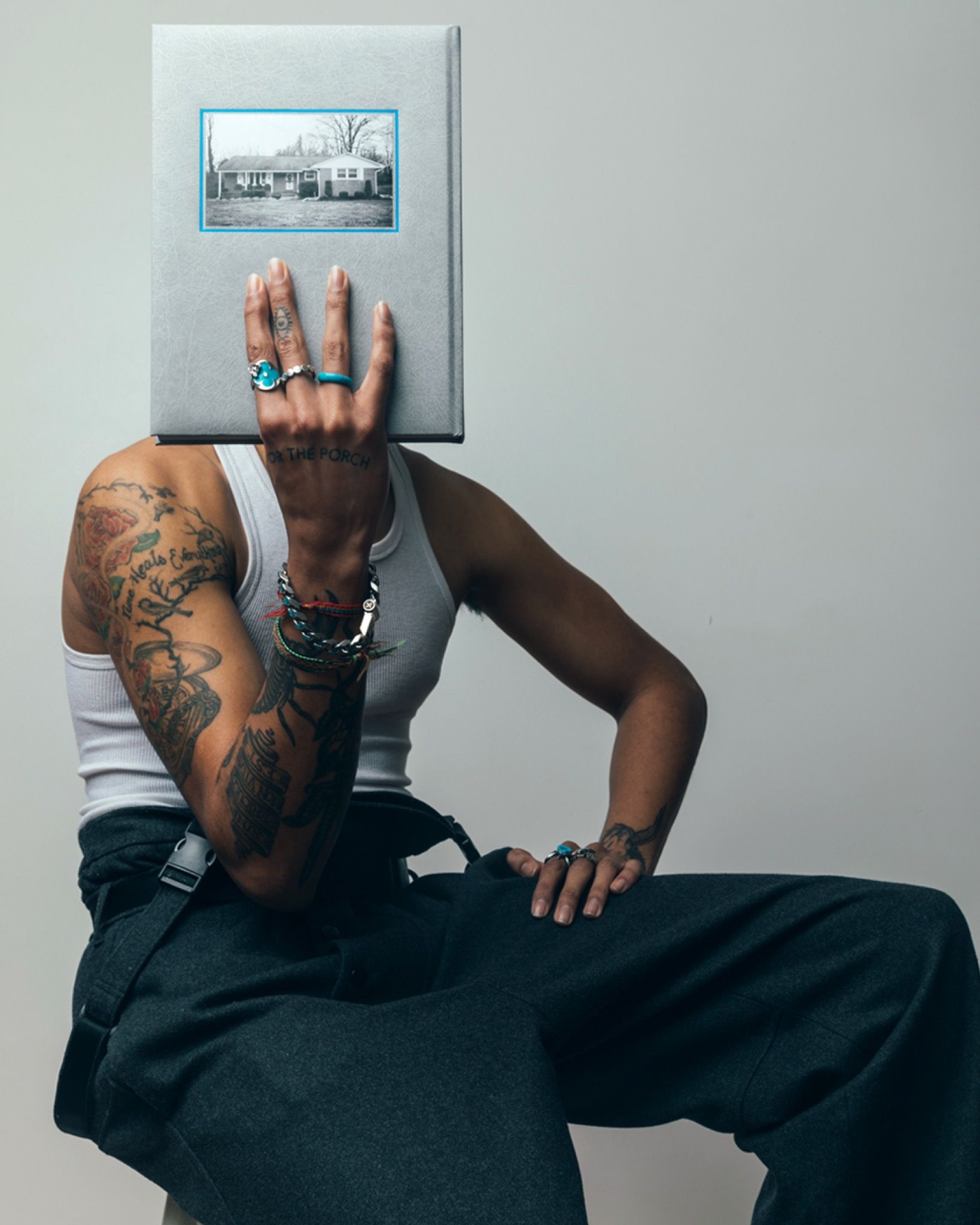

I feel proud of myself in that, recently, I finally disabused people of the “Aria writes about how hard it is to be black and how black people make internet stuff,” mentality. I got to preview the Donald Judd MoMA show in Artforum and then I got asked to write something else for MoMA’s show on video and politics. I was like, “Yes! I will write a formalist take on video after the Internet! Thank you!” With the Greene Naftali show, too. That was the first show that was balls-to-the-wall. I said wanted to make a recreation of this column at Oberlin – Greene Naftali were like, “uh, okay, cool – let’s just do it!”

Can we talk about the column?

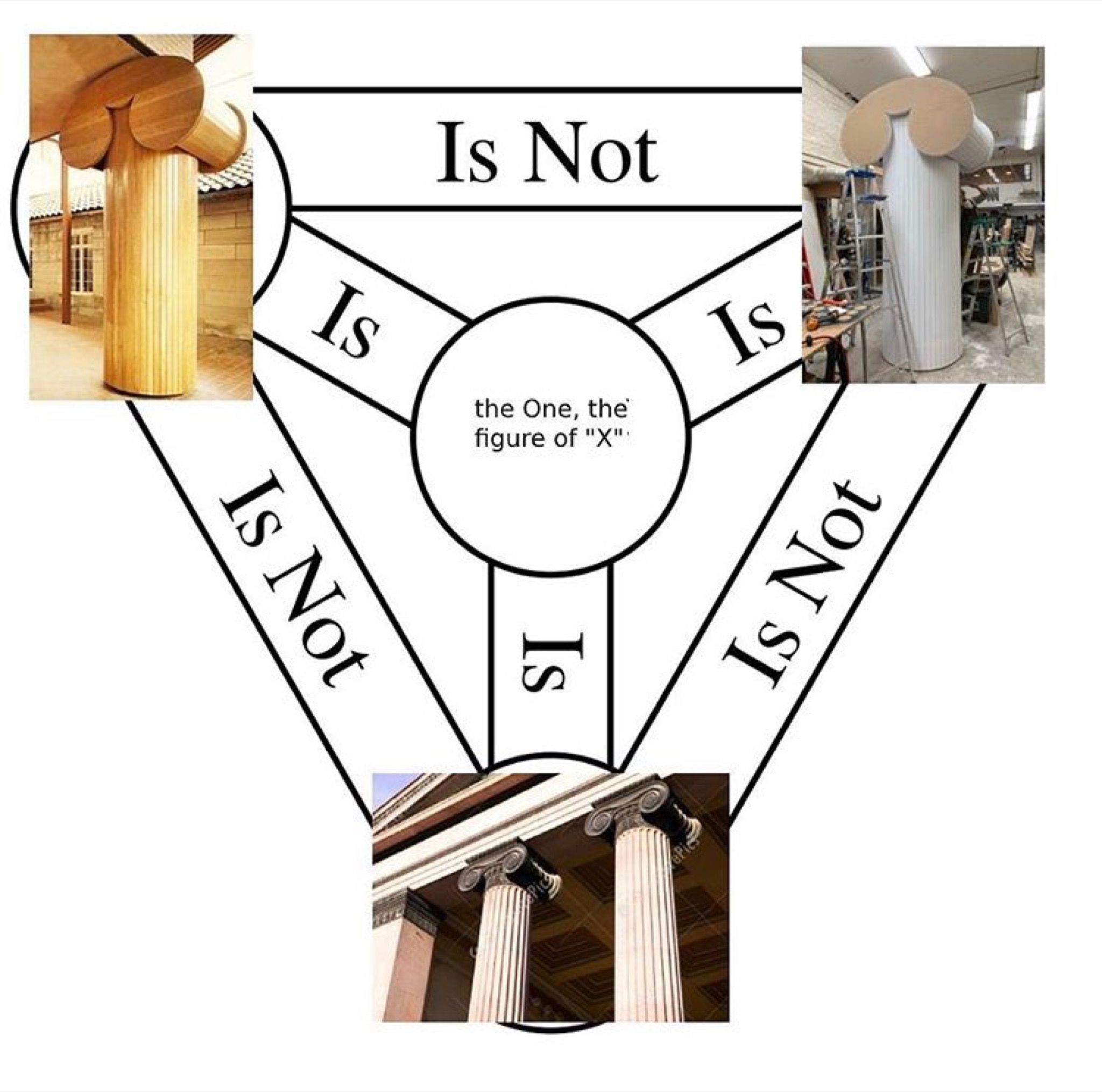

It’s a replica of this Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown designed column that sits at the intersection between the Venturi Scott Brown [and Associates] building and the 1917 Cass Gilbert building on the Oberlin campus–– for the people in the back who aren’t familiar! It’s a funny, very phallic, weird, wooden structure done in the Ionic style. At Oberlin, I was never clear on why it was cool. I tried to research it, but there’s not that much on it, so I decided to just say what I think. It’s an object that folds time over itself. It’s antiquity because, you know, Ionic columns. But it’s also neoclassical because the building next to it is in the neoclassical style, so it’s the neoclassical taking up of antiquity–– so then it’s also postmodern. In the end, it makes a big joke of all these distinctions.

“I like art because it’s pretty fucked. I like trying to grapple with art, and that’s why I got involved in it”

I got really interested in the question: “What does it mean to make a replica of a thing?” If you’ve stood next to the Venturi Scott Brown column, [the replica] has the exact same look and feel. If it’s made of roughly the same materials–– maybe a different paint job, in a different space, but exactly to scale–– is this column not also actually that column? How are they ontologically different objects? Is it because they are in different places that they are different? Are they different because their matter isn’t cut from the same wood?

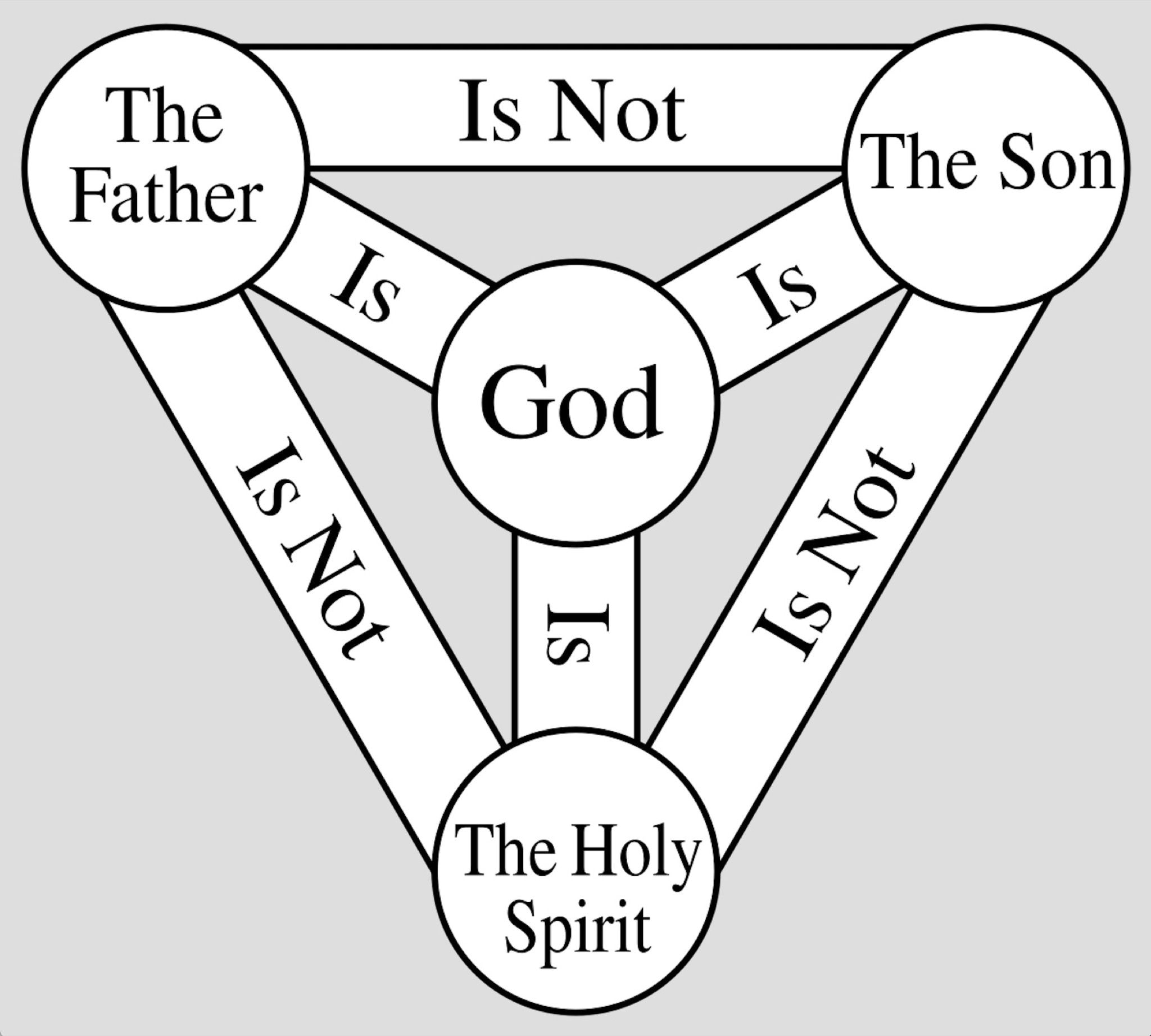

My friend Kyle Hinton said it’s like the Father-Son-Holy Ghost diagram, where at the center is this God-entity. I was into the weird ontology of that. The column sits really nicely on the skyline because there is a Zaha Hadid building right out the window, so it also becomes super architectural. I really wanted to be an architect when I first started at Oberlin, but the professor ignored me for so long that I was just like, “Fine, I’ll leave you alone, it’s okay.”

You mention the architectural interplay at Greene Naftali, but amusingly it sounds much more harmonious and more considered than the situational context of the “original.”

It’s also painted white, just like the other columns that were already in the gallery. People didn’t get that it was a piece. At the opening, people would walk around it, stand near it, and then finally be like, “Wait, what is this thing?” They would look around and it seemed as though people had this reaction that was not upset, but sort of panicked like, “I don’t understand what is going on.” It was really cool.

There’s a disruption in terms of seeing, mirroring, reflecting in many of your sculptures. Your [meta]models made of two-way mirrored glass, for example, bring that question to mind materially. You run into the same density in Mise-en-Abyme. It seems like anxiety is at the core of all of them, but you address it always with a sense of humor.

Mise-en-Abyme 1.0 is a digital sketch that I drew and then sent off to fabricators who rendered it in sculptural form in steel. It’s basically a frame in a picture plane, kind of like a goth Pee Wee’s Playhouse. It’s made of two panels welded together, but it appears to be a single object. I had been thinking about the representational stuff, and trying to middle out a space–– not a refusal, not an acquiescence–– to cut through the middle. I had been trying to do that through excess, studying meme stuff, and the reproduction of images, and then I was like, “What if I just make a non-painting?” It still has my hand in it, though, so it becomes a weird proxy thing. It’s just a flat object that you cannot enter into or extrapolate anything out of.

To me, and pardon the Harry Potter fan nerd language, but the objects become like horcruxes––

I actually talk about this all the time! Does “horcrux” exist as a term outside of Harry Potter?

I think it only exists in Harry Potter. But it’s an interesting vector, because I think the transmission of the self that the term conveys really resonates with people.

Totally. I’m obviously also a nerd, I have a deep love for Harry Potter that I have chosen not to talk about because the worst people are constantly doing it. I’m trying to figure out–– outside of calling it a horcrux–– how to describe my work. I’ve been reading a lot and thinking about the position of art in relation to reality. I have been reading this book called Sonic Flux by Christoph Cox. It’s about sound art, but also about representation and signification, overall. Cox says that for him – and [Gilles] Deleuze, and, he argues, as should be the case for everyone – art must sit alongside life. The horcrux is this totemic object that has taken a piece of the person and [externalized it], so it’s not representing them, it’s not undercutting them, it’s just little bits of them. I think that is so potent.

At the talk I gave in Frankfurt, I showed a video of Robert Morris’ box with the sound of its own making. It collects so much of what I think. I want to achieve that kind of thing, an object that is looped on itself and is enclosed but points outward at the same time. Its production is part of itself, but it also has an aesthetic element. For a while, I wanted to drain my practice of all aesthetic signification, but then I realized that’s no fun. After I made [meta]models I was like, “I’ve emptied myself out, and now it’s time to start playing and putting myself back in.” That box piece of Morris’ is so successful because all it does is what it’s doing. It’s not trying to do something other than that, but in doing what it’s doing, it’s getting at a larger question of what it’s doing.

Even outside of the mirrors and mirroring objects, reflexivity and self-containment seem to be motifs in your work. It’s interesting to ask what it does to confine an object in the sense of the object as an externalization of oneself–

I’ve talked to Rizvana Bradley about this a lot, because we’re both very interested in torqued seriality–– I think Moten calls it that. I’m not making editions or serial works, but they are only individuals until they are not. They enter into a body. It is a bit religious, I guess, like a body of Christ thing. They enter into some sort of collectivity–– similar to blackness–– a collectivity that goes beyond these-things-look-like-those-other-things, but that conceptually forms a mega-artwork. Someday I would like to see everything I’ve made laid out and ask, “What is this world that I have built?” I’m starting to do more film stuff, and I’m realizing that I’m just interested in world-building. All of these objects are just little characters in my Aria Life World.

Credits

- Text: Octavia Bürgel