TYGAPAW is the chosen one

|Octavia Bürgel

TYGAPAW answers the phone from the driver’s seat of a vehicle parked on the side of the road somewhere in New York, appropriately wearing a trucker hat embroidered with palm trees and the Jamaican flag. An alum of the Parson’s School of Design and Pioneer Works’ Brooklyn residency, TYGAPAW – aka Dion McKenzie – is as synonymous with New York City’s underground as they are proud of their Jamaican upbringing. Their monthly event series, Fake Accent, launched in 2014 with the mission to create safe spaces for people displaced along the axes of race, nationality, gender, and sexual identity. Fake Accent has since grown into a label of its own, releasing TYGAPAW’s Handle With Care EP in 2019, and three-track project Ode to Black Trans Lives in June of this year. Get Free, TYGAPAW’s debut full length project, is out today on NAAFI, the Mexican label behind Gaika’s Seguridad and Dengue Dengue Dengue’s FIEBRE, among other recent boundary-pushing electronic projects. “I’m trying to do too much today,” says the DJ and recording artist with a smile, our video call catching them in the vortex of errands and press engagements leading up to their album release.

Octavia Bürgel: When did you begin working with NAAFI?

Tygapaw: I’ve had a friendship with NAAFI for maybe five years now. I met them for the first time at Red Bull Studios in New York, when they were doing a NAAFI versus NON show at the Red Bull festival.

I remember that! Was that 2016?

Yeah, throwback! I was friends with the NON crew, and that’s how we all got into the studio together. It was a great experience. I feel connected to NAAFI geographically, being from Jamaica and them being from Mexico. We are very influenced by one another – reggaeton is influenced by dancehall, and so on. To me that connection felt right. After we met, they would book me to come to Mexico and play NAAFI parties, and the relationship started to build. I’ve always respected their label, loved their content, and the music that they put out. It’s future club electronic music, and I appreciate the level of experimentation involved. Not limiting concepts is always a goal of mine.

Alberto – Mexican Jihad – was in New York last year, and we were on the same line-up with Papi Juice. When I was working on my second EP, Handle With Care, we were talking about doing the release with NAAFI, but I was launching Fake Accent as my own label, and I wanted to establish it first. Earlier this year I decided to start the conversation again, and here we are.

And had you been planning on doing a full length album at that time, or did the record find its form as the year progressed?

For me, a record starts from the concept. It’s a body of work that’s tied into a continued idea – each project is linked to the last. It’s an evolution, and that’s what was going on with this album. I like more of a concept-driven artist, because many of my contemporaries just pump out music. The pandemic hit, and I realized that I wanted to do something that was more linked to my heritage, my ancestry. I have been doing extensive research around Maroon culture within Jamaica. I wanted to create something that was of the time – to make the soundtrack to the revolution, basically.

You used the term “evolution” just now – I had to think of Drexciya, the 90’s Detroit techno act whose mythical origins in the Black Atlantic evolved from enslaved people thrown overboard on the journey to the Americas.

In my research on Maroon culture – what they refer to as Marronage – I read that the plantations were all on the coastline, and the Maroons who revolted and became independent set their communities up inland. I grew up in the country, and the way Jamaica is laid out, the highest terrain of the island is in the middle. Blue Mountain – that’s on the east side of the island, closer to Kingston, but it’s in St. Andrew, in the middle. Mandeville, where I grew up, is also right in the middle of the island. I had access to all the mountains, and I would just go outside my yard and look at them. That, for me, is tranquility. I may not be close to the ocean, but I can feel the ocean – I can feel the ocean through the air.

When I started to read more, I learned that the Maroons survived as hunters and gatherers. They also led the revolution and the rebellion – they were basically going into the plantations saying, “You don’t have to stay here, you can come with us and be free within these communities.” So the idea is that we’re deeply connected to our land, we’re deeply connected to the soil, as well as the water.

The only feature on Get Free is spoken-word narration from writer Mandy Harris Williams. There’s a quality to her voiceover, particularly on the first and last tracks, that makes it sound like she’s underwater.

I always respected Mandy, and when I admire someone I’m very shy about it. When I was in LA last year for a show, we had dinner with Jasmine [Nyende] from Fuck U Pay Us, and we had an amazing time. This time I felt like I could step forward and be like, “I really would love to work with you on this.” I asked Mandy to basically be the narrator of this story – that’s her position on the album. On the dancier tracks, those are my vocals, my voice. I’m injecting my ancestry by speaking patois on a techno track. I’m really experimenting with the genre, but at the same time, I mean, I’m Jamaican. This is the way I do techno – I have to put that island flavor in there. I’m not a writer, but I write through my sounds. Collaborating with Mandy, she could articulate these thoughts in poetry, and she did it so eloquently.

My executive editor just did an interview with the creative director of Lanvin, where they spoke about “embodying” collaboration. I feel like that notion really applies to this album, because even though it isn’t packed with features, it’s clear that you are super thoughtful about choosing who you work with.

Absolutely. I’m a very intentional collaborator, because I believe in energy and synergy. Not everyone clicks – even if you love the person or their music, when you go into the studio it can be completely different. If the conversations don’t feel like everyone is in the same energetic sphere, it can be disruptive to the creative process. I’m very mindful of that. I’m happy – kind of ecstatic, even – with the fact that when I choose the person I want to work with, I take my time to really feel out the energy with that person to see if we’re compatible. I’m not a numbers person. I know that in music, especially popular music, it’s a features game. But I think that I have so much room to be more, to play around. If I was releasing with a major label, they might have more to say about who I collaborate with.

“Electronic music has been revolutionary all along.”

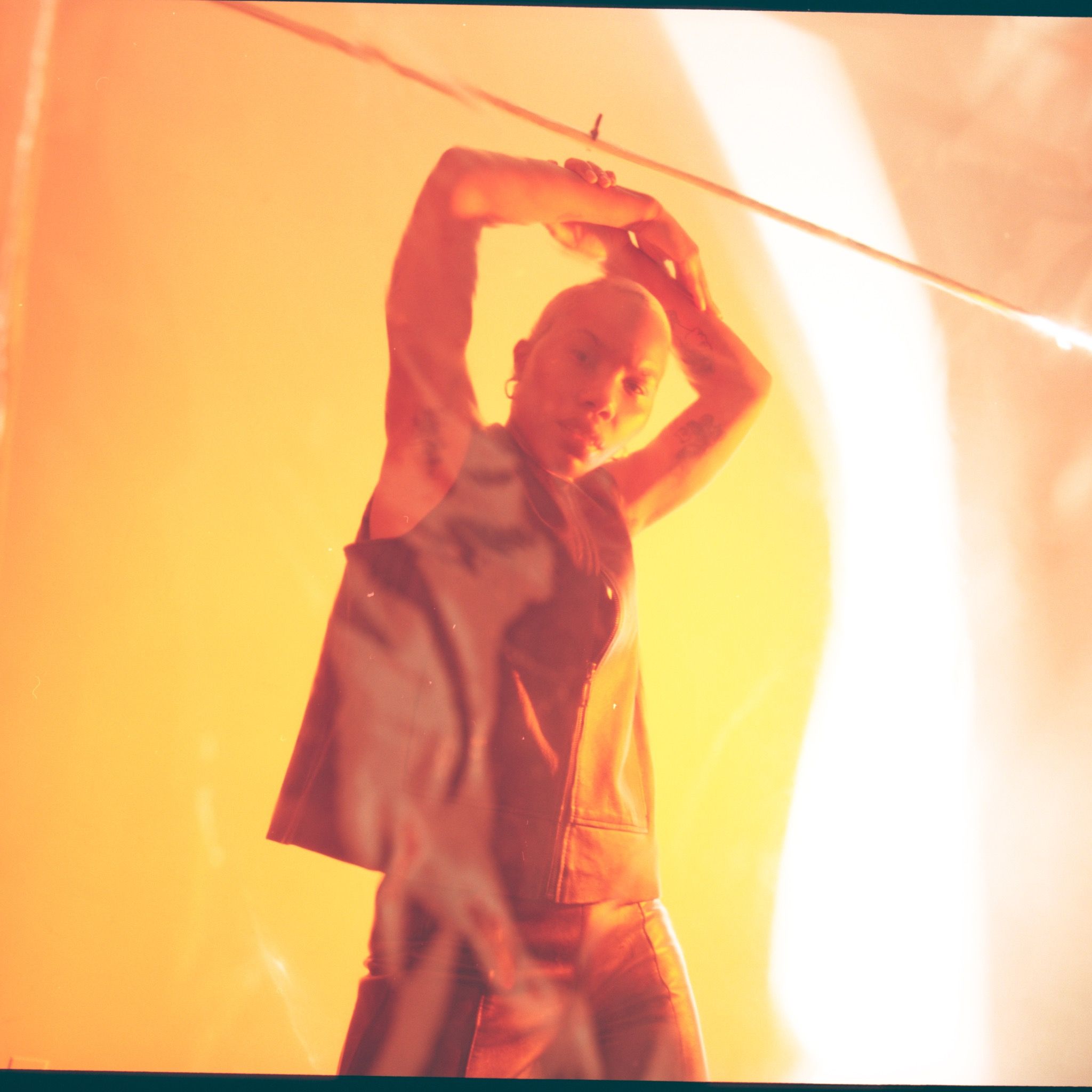

The cover also registers as another layer of collaboration. It says so much about the resilience of the body – every body, but especially the bodies of Black people. It is addressing so much of what is going on right now – COVID, the rallying cry of Black Lives Matter – and definitely underscores the title: Get Free.

It’s a beautiful meeting of meanings. My partner, Avion Pearce, shot the cover. I was under a lot of pressure to deliver because NAAFI is very aesthetically particular. We had very limited time and very limited resources, and that is what this album has been about. This is what Black people do: make the most with what we got. It was the first time Avi and I worked together, and it was a long day. We got that shot in the very last hour, and it was powerful. I was floored when she had the film developed. I couldn’t believe it. I’ve been photographed a lot, and this was a different, really beautiful experience that I’m so happy to speak about. She was directing me, like, “Take your clothes off, we’re going to give body.” I’m like, “I’m comfortable, I love you, you got my body.” That’s the thing: I would never trust anybody photographing me naked. But in this case I was like, “Anything you want, you got it.” That’s how that magic was created.

I really want to drive this point: I choose Black women intentionally. I see the competitiveness that happens in photography – in most creative fields – and a lot of people who are excessively talented get overlooked, especially Black women.

Before we got on the phone, I was reading an interview with LSDXOXO, who says that by-and-large, New York-based DJs and artists are responsible for “a real resurgence in Black dance music” and that “because of the social climate right now, we actually have to take ownership of what’s ours.” Belonging to that community yourself, I wondered if you also had thoughts on this moment in dance music?

Electronic music has been revolutionary all along. We’ve always been working, but now these platforms are paying attention, even though they paid us dust before. I’m so gassed and happy to see you, to be interviewed by you, to see that some change is happening. I think that there is a resurgence – we’re getting the education, the knowledge; we have access to the archives, to know that we have been the pioneers of techno and dance music. The founders are now being interviewed, we’re hearing from them, and we have better access to each other. I love it. We stay with the same energy, so they have to meet us.

Speaking of the pioneers – some of the melodies and instruments on Get Free really harken to that early, pioneering Detroit techno sound.

Absolutely – I’m a 1990s kid. I was hearing this music, but I didn’t have any idea where it was coming from. Growing up in Jamaica, I used to be clowned because I liked to hear all the pop dance music – I’d be trying to DJ on my Walkman. The other kids were looking at me like, “Why are you so strange? What are you listening to?” And they would say, “Why are you listening to white people?” Not knowing that it’s Black music. We also created rock and roll, but white people co-opted it, and erased us from its history. So it’s nothing new – we just aren’t having any of it now. This is the 21st century, there’s too many receipts.

What was it like for you integrating into the dance culture when you arrived in New York City?

Oh my God, it’s like you’re a kid again. Discovering that there is Blackness within this, and that it’s actually very, very Black – you’re like, “Oh shit.” I was so gagged to see my peers who look like me, raving to the music that I love. I always felt like an outsider in Jamaica, but in New York it was like, “You’re not a weirdo, you’re just like us.” It’s either dancehall, reggae, or soca when you go to parties in Jamaica. But there is a beautiful aspect to that – Jamaican dance culture is very colorful, it’s very lively, very rebellious. Those concepts can transfer from one genre to the next. That Jamaican flair that I have – it just works for techno, it works for house and electronic music. I think that as the internet opens up more and more, SoundCloud and other platforms make it easier for Jamaican music to be heard globally. That intersection is finally happening.

“I’m injecting my ancestry by speaking patois on a techno track.”

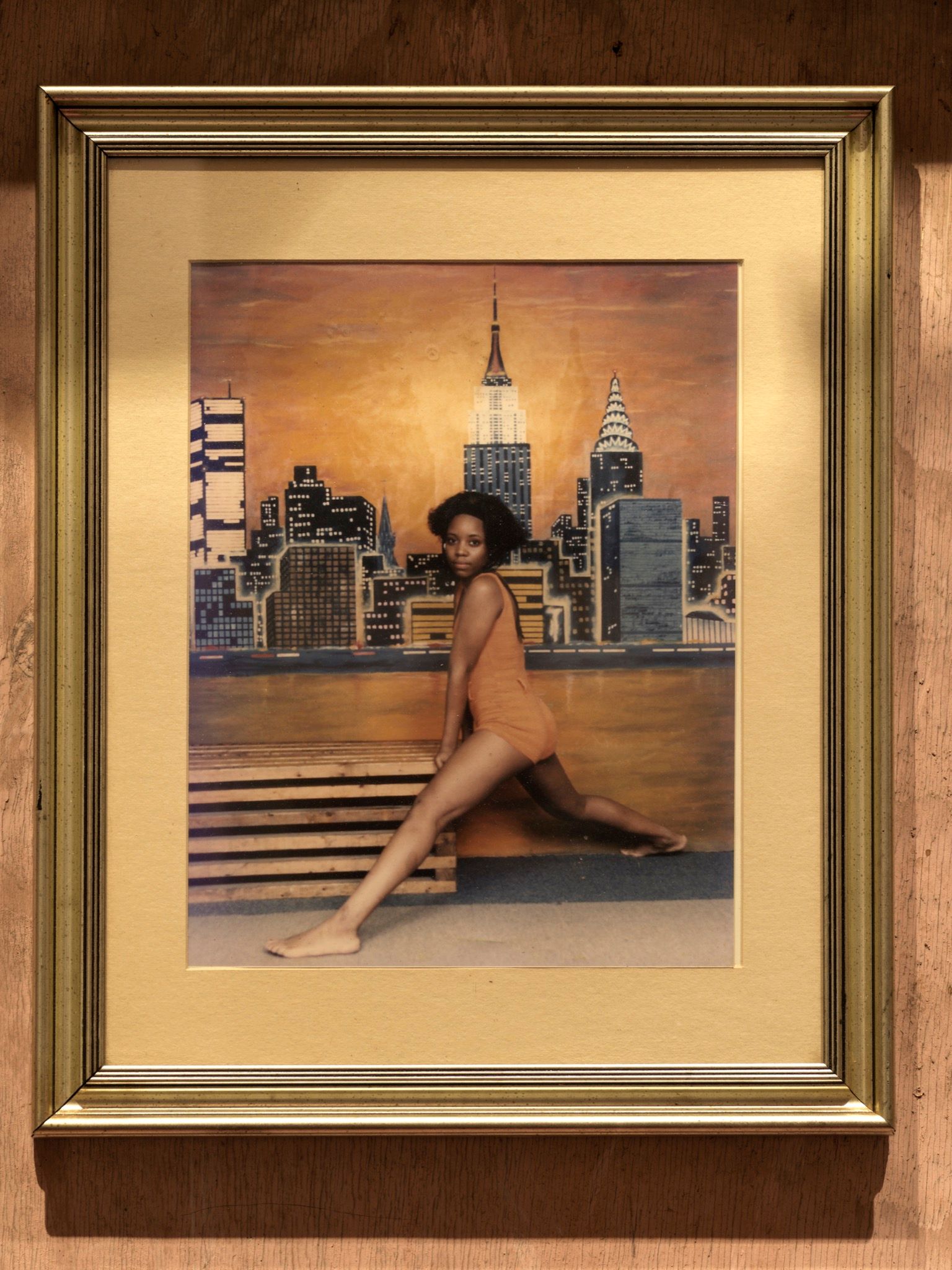

There’s a show up at Red Bull Arts right now – Akeem Smith’s No Gyal Can Test. Smith uses archival imagery of dancehall parties in the 1980s and 90s, and the footage is so exciting – the energy, the vibrance, the outfits, the sex. Watching the video of these dancehall parties and superimposing that over my experiences in New York and even in Berlin – it’s all the same thing: Black people around the world trying to shake off the stress.

It was beautiful to see that show. Those are my relatives – it felt like taking a walk down memory lane. I always say that this music is liberation. I was exposed to dancehall sessions that look just like that, and all of the fashion connected to it. Coming to New York and seeing the same thing – I mean, these are Jamaicans that never even left the island, doing the same fashions. It’s the way we express ourselves, and it’s part of the rebellion. If you don’t know much about Jamaica’s political climate, or how we were colonized by the English – the general public is very conservative. Dancehall grew from the need to rebel against that conservatism.

There’s a video piece in the back gallery that juxtaposes the fall of the Twin Towers with footage from a dancehall party that was taking place at the same time, several thousand miles away. My family came to New York right after 9/11, and I feel that the attitude in New York in that immediate aftermath was a hyper-specific combination of solidarity and suspicion.

I came to New York the year after, too. Getting a visa after 9/11 was literally a lottery. They took the number down from 500 to something crazy like, 50 visas issued, and I was part of that selection. They turned down so many students, and I got my student visa in 2002. It sometimes feels like the universe was like, “No, you are the chosen one. You’ve got to do this work.”

Credits

- Text: Octavia Bürgel

- Photography: Avion Pearce