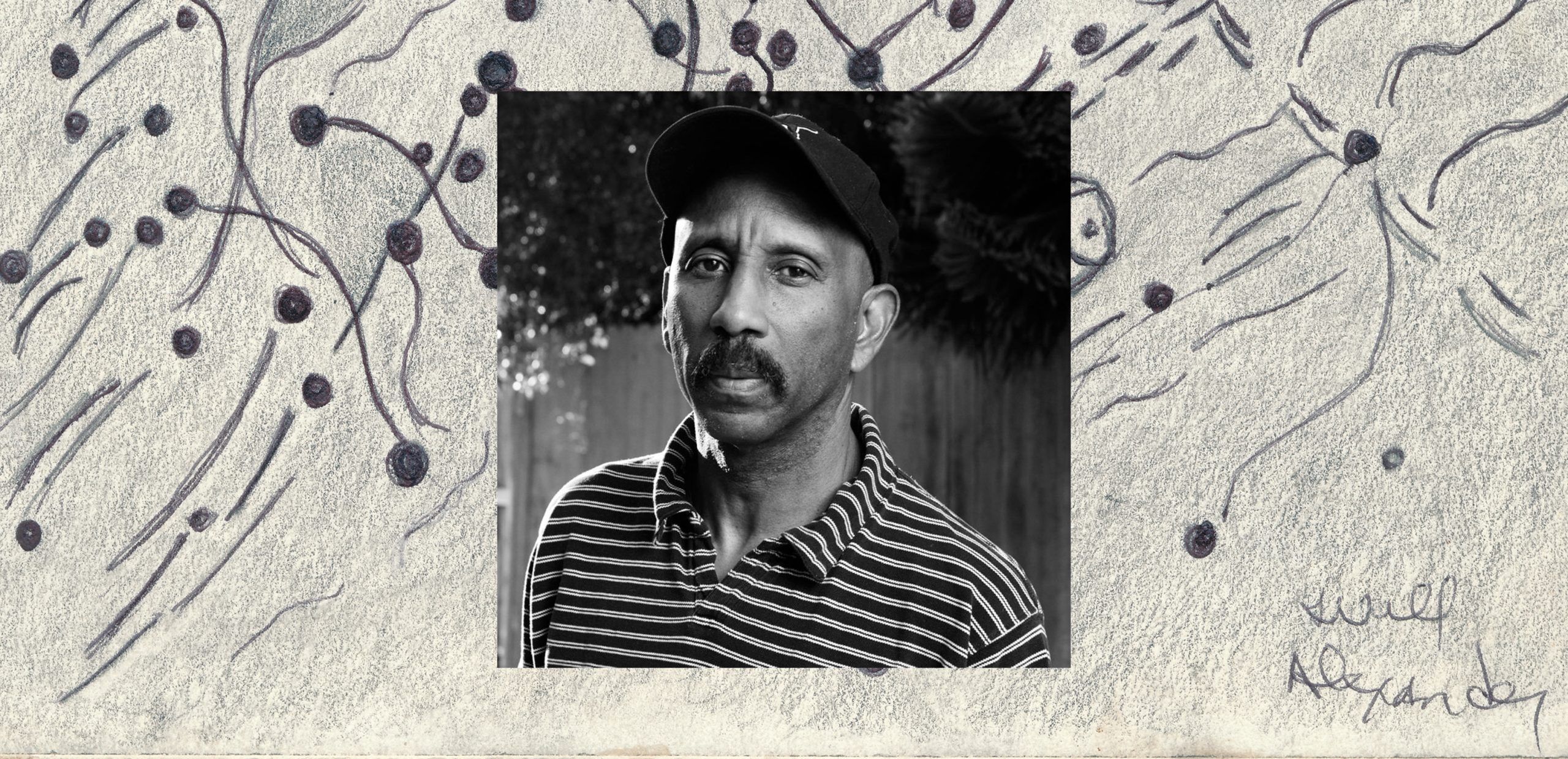

The JULIUS EASTMAN Revival

|David Grundy

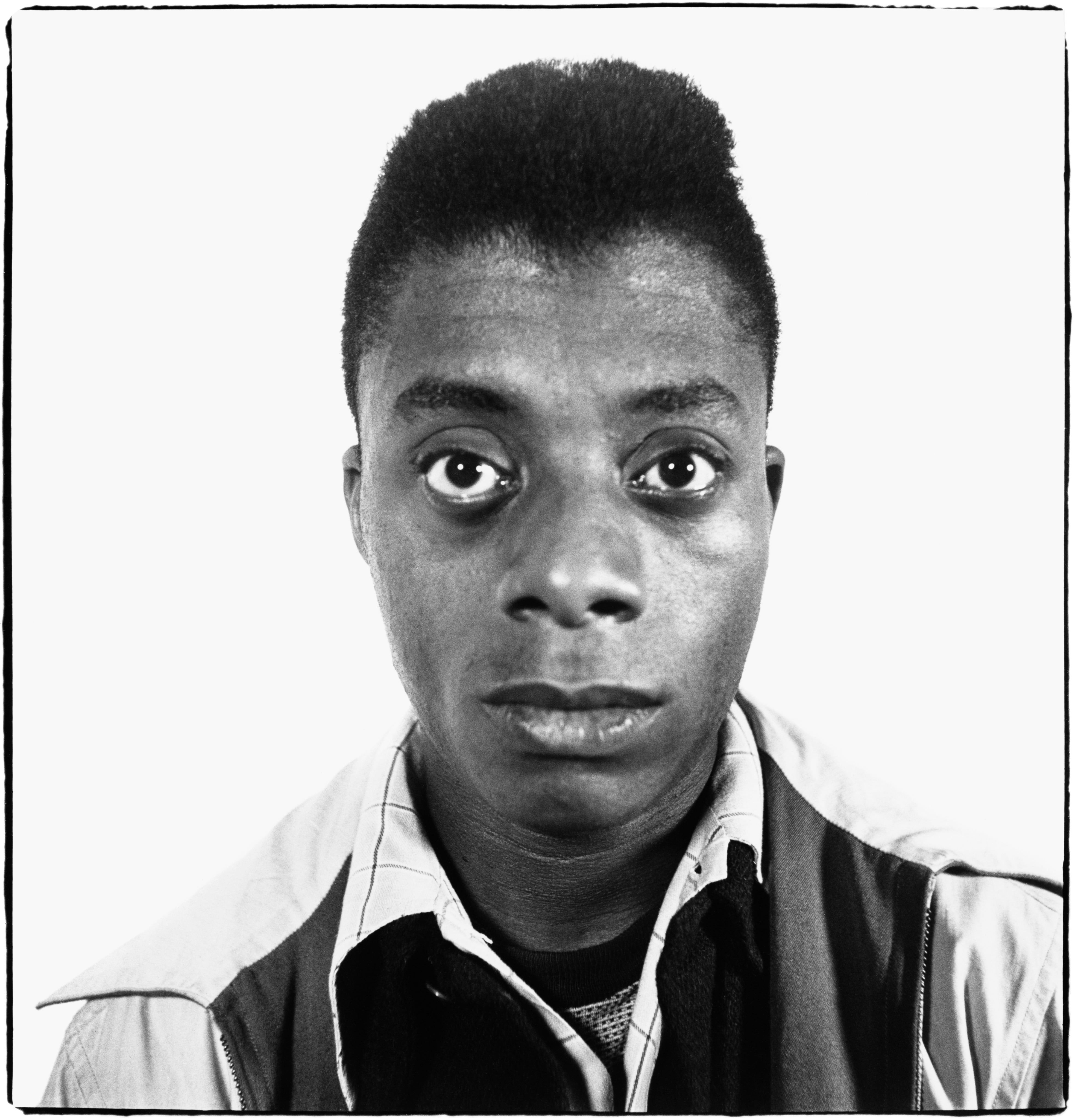

Composer, singer, and multi-instrumentalist, Julius Eastman’s work suffered years of neglect before a recent revival of interest, signaled by festivals, recordings, and performances worldwide. But Eastman’s pieces challenge the very idea that his work could be revived without also dismantling and reordering the social structures that surround classical music. During the decades in which it was written, from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, his music insistently challenged the social rituals around it: a product of counterculture, of liberation struggles, of an often utopian reimagining of music within the context of the Cold War, AIDS, and Reaganism. And today it still has a radical effect, in times no less bleak and no more progressive.

“Music was born in 1700, lived a full life until 1850 at which time music caught an incurable disease and finally died in 1900.” At least, so one might surmise, given the present state of things. The composer Julius Eastman makes this point in his short, provocative essay “The Composer as Weakling” (1979), tracing a brief but ambitious history of Western “classical music” to suggest a radical shift in how we view the relation between composing and performance. Since the days of church organists, court composers, and itinerant troubadours, Eastman argues, there’s been a split between solo performers, star conductors, and the composers now rendered lonely “queen bees” cut from the collective process of music-making. To remedy this, Eastman suggested, the composer must “reassert him/herself as an active part of the musical community,” becoming a “total musician, not only a composer. To be only a composer is not enough.”

Since the release of the box set Unjust Malaise in 2005, Eastman’s own reputation as a composer has undergone a significant revival. From remaining virtually unheard in the wake of his tragically early death in 1990, his works are now regularly performed across Europe and America. In 2016, Mary Jane Leach and Renée Levine Packer co-edited Gay Guerrilla, a series of essays on Eastman’s work which revealed fresh facets of his art. The same year, the London Contemporary Music Festival put on the first major festival of his music, followed by the “That Which is Fundamental” exhibition and concert series in 2017. Since then, one more book has appeared, from Berlin-based gallery Savvy Contemporary, and Eastman’s pieces have featured on programs around the world, including a festival at Munich’s Lenbachhaus, with a final concert on March 14, 2022.

Yet, as Eastman’s 1979 essay suggests, his entire aesthetic challenges the very notion of compositional authority and the structures of concert programming involved in today’s revival of interest in his work. He was, above all, a working musician, whose compositional methods incorporated indeterminacy, improvisation, and adaptation to on-the-fly situations, and his pieces were often written for indeterminate forces, whether that would be the unusual instrumentation of the S.E.M. Ensemble or whichever performers were at hand.

From 1968 to 1975, Eastman worked in Buffalo with the S.E.M. Ensemble, of which he was a member, to destabilize performance expectations and environment through spoken text, unconventional instrumentation, exaggerated theatricality, parody, and irony, while laying the ground for the peculiar combination of fragility and grandiose strength that would characterize the sound of his mature works. Amongst such pieces, recordings have recently surfaced of Macle (1971), in which voices shift in pitch like the droning tones of bees, and Creation (1973), where there are stuttering piano figures, more mellifluous flute lines, percussive rings and taps, and ghostly quotations of popular songs like “The Girl from Ipanema.” “Show us, show us … the pure tit,” proclaims Eastman, setting off a burst of cowboy harmonica in protest. During this time, Eastman also produced one of his most accessible works, the joyous Stay On It (1973) which stretches out the buoyant energy of the three-minute pop song over a full twenty minutes.

Moving to New York, Eastman turned to the more driving and intense sounds of his best-known pieces, such as the 1979 N— Series (Gay Guerrilla, Evil Nigger, and Crazy Nigger), or the multiple cellos of The Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc (1981), which emphasize darker tones, complex unison and phase playing, and an increasingly ghostly, intense emotional tenor. Finally, as Eastman faded from the music scene in years of homelessness and addiction, there were the more fugitive works of the mid-late 1980s, sparser pieces, often designed for performance by Eastman himself, on piano or with voice, which condense, crystallize, and fracture in equal measure.

Eastman wrote a significant number of works for multiples of the same instrument – ten cellos, four pianos, seven trumpets. “There is something very homosexual about using ‘multiple instruments of the same kind,’” quips Malik Gaines. This queerness in turn links to the utopian social vision that suffuses much of Eastman’s work. But if Eastman sought the one in the many, he also worked with the many in the one – himself. As Mary Jane Leach comments: “He had a habit of situational writing, using whatever resources were available. When all else failed, he would create solo works for himself, most of which weren’t notated.”

This was particularly the case in his later years. By the time Eastman wrote out the score to Piano 2 (1986) for former S.E.M. compadre Joseph Kubera, his manuscripts were “erratic,” written in a “shaky hand”; noteheads are missing, barlines absent. The piece, as recorded by Kubera on the record Book of Horizons (2014), centers on a condensed, desolate, three-minute slow movement, in which chordal figures slowly rise and fall with a kind of remorselessness yet plangency around sparse figures that alternately repeat or trail off, like a sentence half-spoken, left unfinished. The finale ends on something that is almost – but not quite – harmonic resolution. Eastman’s last surviving piece is Our Father (1989), a brief setting of a liturgical text for two male voices – “dos hombres,” as the score puts it – which soars with a kind of giddily austere devotional focus. Not long after, Eastman passed away.

Much of this work drew its strength from Eastman’s particular qualities as a performer – The Zürich Concert, a 1980 performance released by New World Records in 2017, is a case in point. Yet, paradoxically, his late scores – when there is a score – also definitively move beyond the notion of a composer’s style and towards the way the score can activate the impulses of its performer. Buddha (1984) is typical. Notes occur on an indeterminate series of staves inside a shape reminiscent of the Zen Buddhist enso – a circular form constructed from one or two brushstrokes in which mind is relinquished so that body can create. The piece can be interpreted any number of ways: from the insectile rumblings of the Kukuruz Quartet’s 2014 version for four pianos, to the stripped-down, a cappella rendition I saw the extraordinary singer Elaine Mitchener deliver at the 2017 London Contemporary Music festival.

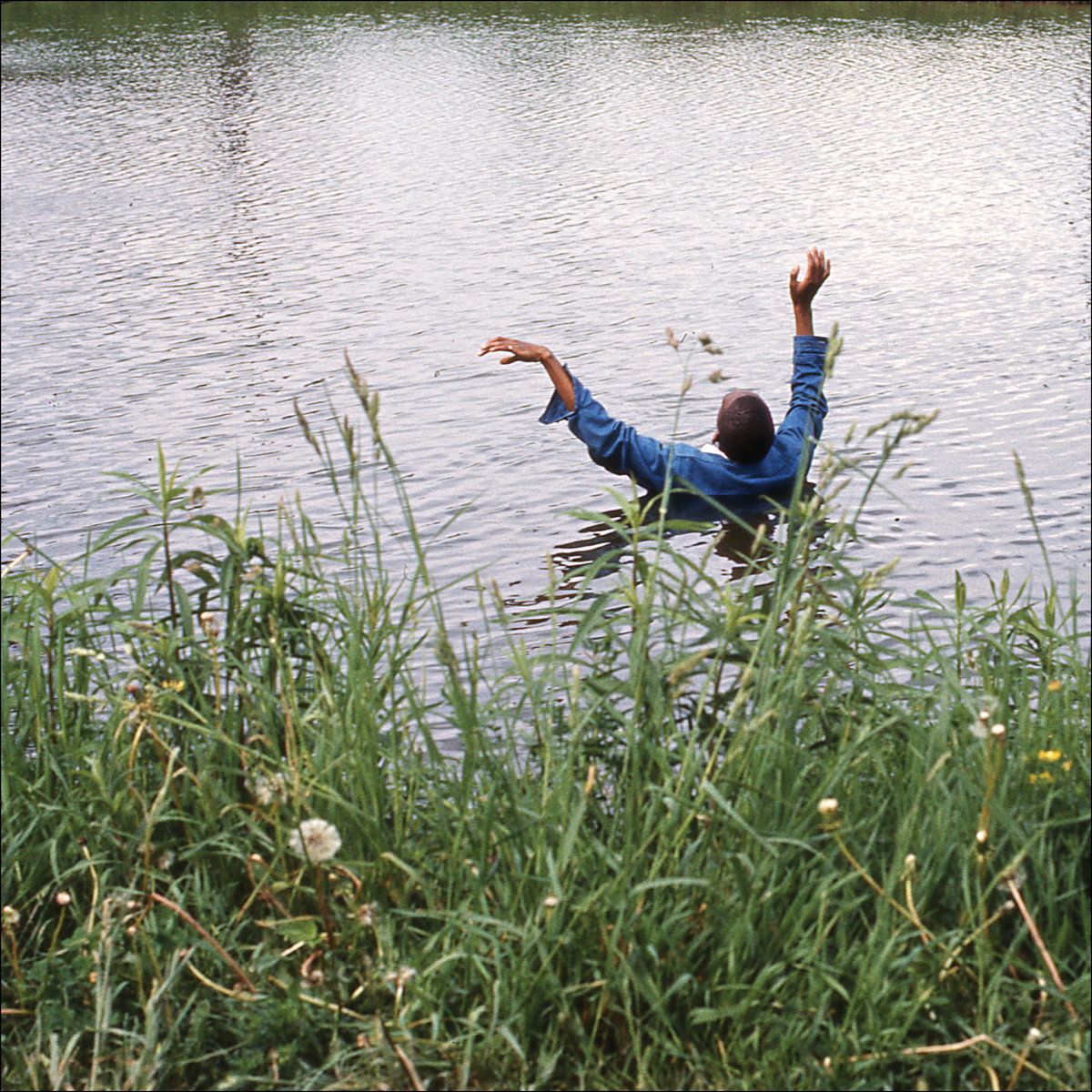

Eastman’s own performances suggest that what should be central to such performances is a quality of intense – in his case, devotional – focus. In 1986, he provided music for a dance piece by Molissa Fenley entitled Geologic Moments. As Fenley writes, in the dance, “shifting geological strata can be used as a metaphor for changing emotional states, especially those that occur suddenly.” The metaphor of geology is an apt one for Eastman’s music, too, as slower, imperceptible processes of erosion, sedimentation, and change become the basis for new solidities of earth, new grounds for growth. Combining piano with vocalized, fortissimo declamations of a declaration of a pan-religious faith – “one god, and nothing but god” – that are triumphant and fearful in equal measure, Eastman’s piece incorporates both his characteristic slow, extended morphing of repeated figures, and abrupt declamation surrounded by void-like space.

For those expecting Eastman’s pieces to follow the repetitive, rhythmic, classically minimalist styles of Eastman’s more popular pieces – Femenine, the N— Series, Stay On It, or The Holy Presence – works like these – Buddha, Hail Mary, Our Father, Piano 2, One God – may surprise. They are about silence as sound, each brief phrase assuming a weightiness through it slowly hanging into space. Sometimes Eastman will point up an allusion to the classical canon in the score, such as labeling a particular phrase “Wagner” or “Chopin,” but otherwise the works’ austere textures are uniquely Eastman’s own.

The music’s simplicity of means belies the emotional challenge of its textures, as unremittingly sparse as Eastman’s Buffalo-era work was buoyant and full. For Eastman, his friends reported, each new tribulation seemed a spiritual test of strength and inner resourcefulness – a reduction to what he called “that which is fundamental.” Without ever losing his socio-political analysis, material difficulties were interpreted along the lines of spiritual trials. While not the whole story, we can see Eastman’s late work as a kind of distillation of his style, reflecting his personal circumstance, a turning inward and upward, as well as downward, to the earth (“that which is fundamental”).

“Rather than repeating the world as it is, it seeks to end it, to transform it, to reveal – as the etymology of ‘apocalypse‘ and of ‘revelation‘ after all suggests – those possibilities that were hiding in plain sight.”

Eastman had used a Lutheran hymn as the rousing climax to Gay Guerrilla on the brink of an era in which, thanks to the rise of the religious right, that legacy of Protestantism was literally killing gay people. As such, his use of religious elements might be aligned with Diamanda Galás’ Plague Mass in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine a few months after his death. But whereas Galás turns Christianity’s fire and brimstone against itself, Eastman instead brings out the ecstatic, erotic stringency of mystics so often enshrined in women or feminized persons from Joan of Arc to St. Sebastian: asceticism and eroticism, desire and transformation; Joan of Arc, Julian of Norwich, Hildegard von Bingen, St. Teresa of Ávila, St. Sebastian, St. Francis. A composer who wrote pieces with numerous religious titles, he was anything but conventional in his faith(s). This was, after all, the composer of pieces called Not Spiritual Beings and Praise God from Whom All Devils Grow.

In his late works, Eastman’s spirituality seems to serve as a way of both attesting to and imagining otherwise material conditions suffered as a gay, Black, sometimes homeless person. It builds on this figuration from the Christian tradition of a counter-lineage: that of the spirituals, of Catholic sainthood, in which – against the backdrop of AIDS and nuclear catastrophe – suffering is both a world-ending and world-redeeming event. Rather than repeating the world as it is, it seeks to end it, to transform it, to reveal – as the etymology of “apocalypse” and of “revelation” after all suggests – those possibilities that were hiding in plain sight.

At the same time, Eastman’s music clings to the social, to what in his own life slipped away. In a 1981 performance called Taking Refuge in the Two Principles, Eastman sings:

“I place my friends around me

I place them on my left side

I place them on my right side”

“In an unjust society, Eastman suggests, full freedom can only be lived at the cost of self-destruction: the pursuit of 'that which is fundamental' – sexually, spiritually, musically, in terms of an entire life and an entire way of being – refusing the position of victim and instead claiming that of 'warrior,' even to that of death.”

Eastman’s Symphony No. II – one of his very few works for large orchestra, completed by Luciano Chessa and performed a few weeks ago by the New York Philharmonic – was a gift for his lover, R. Nemo Hill, on the occasion of their breakup. On the score, Eastman wrote:

“On Tuesday, Main and Chestnut at 19 o’clock, The Faithful Friend and his Beloved Friend decided to meet. On Monday the day before, Christ came, just as it was foretold. Some went up on the right, and some went down on the left. Trumpets did sound (a little sharp), and electric violins did play (a little flat). A most terrible sound. And in the twinkling of an eye the Earth vanished and was no more. But on Tuesday, the day after on Main and Chestnut at 19 o’clock, there stood the Lover Friend and his Beloved Friend, just as they had planned, embracing one another.”

Love survives the end of the world that music invokes and, in turn, music survives the destruction it itself heralds, in a kind of joyous self-abolition. As Chessa put it in a panel discussion last month:

“The symphony is extremely ambitious. I mean, the symphony is an eschatological reflection over the end of time. In the note of the symphony, Eastman is writing, essentially, I had an appointment with my lover, and then the world ends. And yet, after the end of the world, I will be still meeting my lover at the time that we have decided to meet.”

Viewed cynically, the Julius Eastman revival, taking place long after his death, is a convenient way for the classical and new music worlds to plug what might euphemistically be called a “diversity gap.” Yet even as he’s ushered into the concert hall, Eastman’s music challenges the social rituals around it: a product of counterculture, of liberation struggles, of an often utopian reimagining of music within the context of the Cold War, AIDS, and Reaganism, in times no less bleak and no more progressive.

In Eastman’s life, as friends and lovers have suggested, Eastman took his interpretation of what it might mean to be a gay guerrilla to its utmost. For Eastman, the figure of the guerrilla had to with martyrdom and ideas of sainthood as much as political activism and struggle – or the overlap between the two that he had invoked in his spoken introduction to the premiere of Gay Guerrilla.

Now the reason I use Gay Guerrilla – G U E R R I L L A, that one – is because these names: either I glorify them or they glorify me ... At this point, I don’t feel that gay guerrillas can really match with “Afghani” guerrillas or “PLO” guerrillas, but let us hope in the future that they might ... So, therefore, that is the reason that I use gay guerrilla, in hopes that I might be one, if called upon to be one.

“He fancied himself a martyr,” remarks Nemo Hill. “I mean, it’s a very unmodern sensibility, a very religious sensibility.” In Eastman’s life and work, emancipation is taken to its ultimate. “I shall emancipate myself from myself,” Eastman proclaimed in a spoken introduction to Holy Presence of Joan of Arc, addressed directly to the Medieval saint. In an unjust society, Eastman suggests, full freedom can only be lived at the cost of self-destruction: the pursuit of “that which is fundamental” – sexually, spiritually, musically, in terms of an entire life and an entire way of being – refusing the position of victim and instead claiming that of “warrior,” even to that of death. And it’s both in spite and because of this utter, difficult commitment that his music – and the complex legacy it leaves for today’s artists – continues to live on.

Credits

- Text: David Grundy